Tattfoo Tan: Designing Rituals

Tattfoo Tan, New Earth Banners, 2019 [photo: Tattfoo Tan; courtesy of the artist]

Share:

With Heal the Man in order to Heal the Land (March 2 – December 29, 2019), Tattfoo Tan presents a large-scale realization of his social practice in the Newhouse Center for Contemporary Art galleries at the Snug Harbor Cultural Center & Botanical Garden. The installation is geared to interact directly with visitors and precipitate self-reflection and instigate creative output. Tan’s work is far from aggressive or confrontational, but he still manages to insistently involve visitors in a process of learning that activates creative facets of their personalities. In Nuevo Americana Recipes (2009) and FIT Heirloom Recipe (2009), inhabitants of Staten Island and students at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology contributed family recipes, resulting in participants’ applying skills in photography, graphic design, and social media to create a publication. S.O.S. Mobile Garden (2009) encouraged participants to discover and utilize discarded shopping carts, buckets, baby carriages, luggage, and even office chairs and coffee tables to generate miniature gardens that could be docked throughout their environments, offering tiny accents of green in an urban setting. On the occasion of his exhibition at Snug Harbor, I met Tan to discuss his tactics of creating audience engagement and participation, and he elaborated his social practice and the spiritual side of his art.

Tattfoo Tan, S.O.S. Mobile Classroom, 2010 [photo: Tattfoo Tan; courtesy of the artist]

Will Corwin: How do you envision a studio? For your current exhibit at Snug Harbor, Heal the Man in order to Heal the Land, you’ve literally emptied your studio of its furniture, your kitchen of its pots and pans, and your office of its typewriter in order to create a series of displays that illustrate Buddhist principles. I’m sitting here in your studio and it’s largely empty! Do you believe in the idea of artist materials, or is it more about utilizing what’s around you?

Tattfoo Tan: For me the artist’s studio is a lab, a place where you experiment. I work on things—without knowing why I’m doing it—sort of just testing out. A lot of my work comes from writings, so in some ways the studio also is a space to write, not just doing tangible material things. In my artwork, the tangible stuff is usually recycled or reused or repurposed because I’m not in the art market, so I don’t see a purpose in keeping them for art historical sake. I’ve shown it and it’s served its purpose, so the material can have a second life.

WC: The current exhibition first has a didactic element in which you illustrate the self-realization concepts you’re engaging, followed by a cooperative element in which you generate a space for the visitor to meditate, and lastly there’s a work zone where the spectator is invited respond by creating their own version of a deck of Tarot or prophesy cards. This means that you, as the artist, are represented in the context and exhibition. What is the lasting artwork that is generated?

TT: It’s documentation on my website, which is a lot of tags, pictures—really [image] heavy. It is sort of an archival site rather than a portfolio site. I don’t edit things. I just chuck it out there, so that I can remember what I’ve done personally. It’s not just for the public to see, but it’s also for me to recollect: tracking back over the years. The final output is a portfolio book usually—to encourage people to replicate and be inspired by my projects.

WC: So the idea of replicating your projects—you’re not against that, and you’re not against other people participating?

TT: Participating, altering, inspiring—some of them replicate it 100%, so they give me credit; some people just take the ideas and get inspired to do other things. It’s a way of saying that art is not bound by an artwork. The artwork grows beyond the artist.

Tattfoo Tan, I’m Not This, 2019 [photo: Tattfoo Tan; courtesy of the artist]

Tattfoo Tan, Gratitude Jar, 2019 [photo: Tattfoo Tan; courtesy of the artist]

Tattfoo Tan, New Earth Resiliency Oracle Card (contributed card by Yaya Wang), 2019 [photo: Yaya Wang; courtesy of the artist]

WC: How often have your projects been replicated?

TT: The Nature Matching System especially. People have done it in other states, and they’ve sent me pictures.

WC: Nature Matching System created an equivalency between color chart systems, like Pantone, and nutrition requirements, blending the worlds of advertising, graphic information representation, and wellness, and it straddles both art and mass–produced products like placemats and billboards. You have a phrase that encapsulates this concept [of artwork intended for replication]: Franchise Modal Art Project. Are you able to make a living using the idea of the Franchise Modal Art Project? I don’t know if you want to say this, but how satisfied have you been with other people utilizing your projects?

TT: So, the franchise is not really to make money but to have control. McDonald’s—or whoever is franchising something—they want to control the outcome. It’s being able to have that control and being able to have feedback from the participants somewhere else, in some other location, that’s what I meant by franchise. A lot of my projects, even though they are things that I’ve done recently, I encourage people to do them without me. In normal practice, museums or galleries really want artists to activate their own artwork; it serves as a sort of “artist is present,” like a star. “This is someone special, we have hired this artist and they’ve come to our museum to do this thing.” I like to reverse it, saying the idea of the artist is in the museum and we are all activating it and even changing it a little bit.

WC: What is your background, spiritually speaking? You talk a lot about spirituality in the exhibition at the Newhouse Center at Snug Harbor, Heal the Man in order to Heal the Land—what did you grow up with?

TT: So, I grew up as a Taoist. When I was growing up, to me, it was just superstition—it was what everyone was doing in the neighborhood. When I asked, “Why am I doing this ritual,” “why am I supposed to pray to these idols—who are they?” My parents weren’t able to tell me the reason. So, it was blind faith.

WC: They didn’t explain to you who or what the idols were?

TT: It wasn’t their fault. They didn’t have the in-depth knowledge for the reasons … we were doing it.

WC: When did you first get your head around Taoism, or when did you say, “I’m not interested in this and I want something else?”

TT: I just take certain tools out of a particular religion, or practices, and try to use it on myself and see whether it works for me, so I’m an amalgamation of different practices. You [might] identify yourself with seeking the highest divine, but then you need the ladder to climb up there, and that ladder belongs to certain traditions, and you might need to borrow it for a while. Once you reach the top of the ladder you might need a rope, and that rope belongs to another tradition, and you might need to borrow it for a while. That’s how I see my own particular belief.

Tattfoo Tan, Wood and Stone, 2019 [photo: Tattfoo Tan; courtesy of the artist]

WC: You talk a lot about this idea of realizing the true self. What exactly do you think the true self is?

TT: According to the knowledge that I understand, the easy way, the straight answer is, no one knows. The more black and white way is that the true self is God. And when you discover the true self, you discover you are the divine, you are God reincarnated as a human.

WC: Much of what you talk about is discarding, peeling away layers of obsessions and mortality and ego. I’m playing devil’s advocate. I do agree with you on a lot of this, but why is ego bad? We think that ego is bad, but why are these things like obsessions with mortality, ego, why do they have to be peeled away?

TT: They don’t have to be peeled away. It’s your own choice, or your own tendency, or your own calling. A lot of people like the drama in life. That’s why they watch soap operas, reality [shows]. I wanted to simplify my life a little bit; maybe own fewer things. And at some point [I realized that] these emotions that I have, I don’t like them. This jealousy that I have—I want to get rid of it. No one can force you; you have to be consciously saying, “I have to peel away this layer of emotion called jealousy.” And then this layer called fear—“I’m always so fearful of being judged, so I don’t want to have that anymore.” Once you peel away [these emotions], what’s left? It’s like an onion. You keep on peeling and peeling and there’s nothing in there, so you discover that you are nobody—nothingness—that’s your true essence.

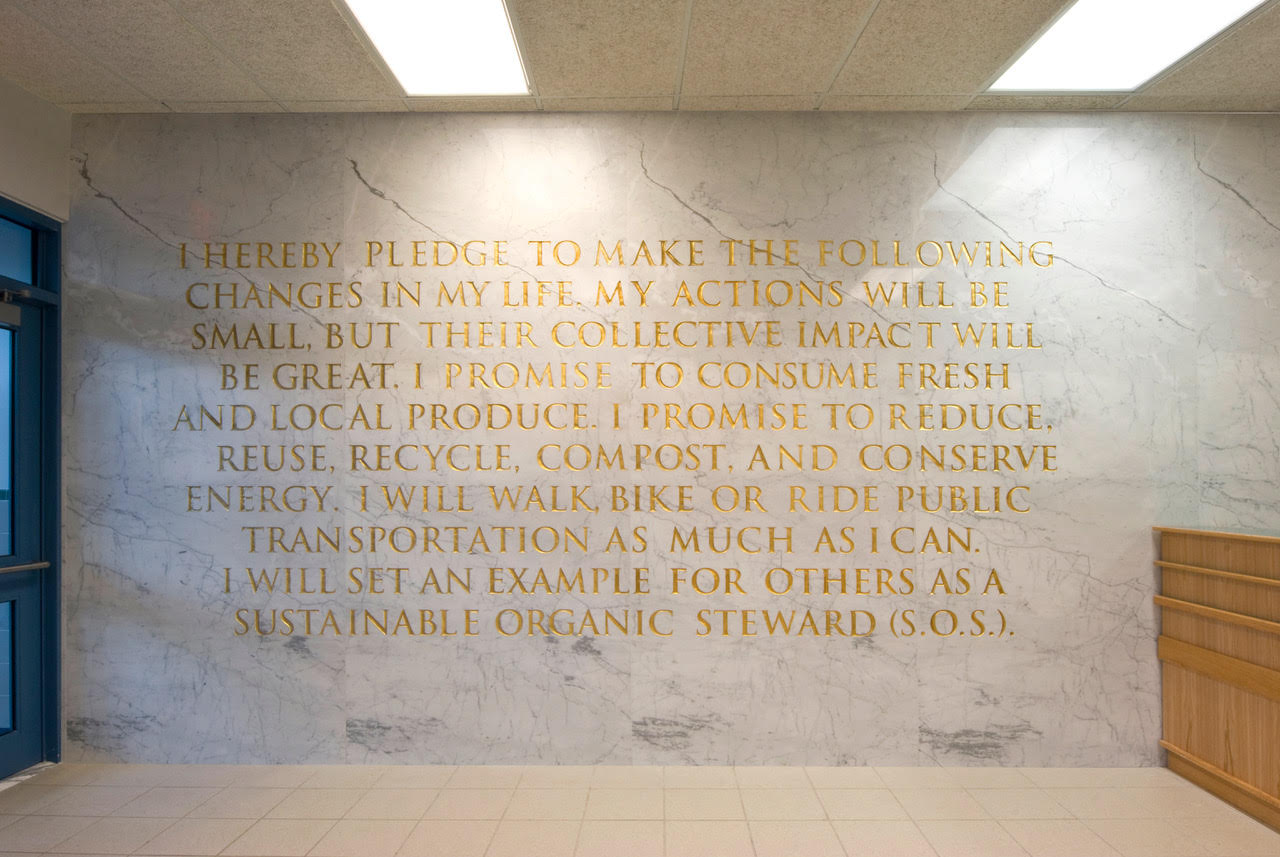

WC: In terms of generating rituals, in the past you’ve generated collective works in which the viewer has to participate in order for the work to be complete: I’m thinking of your S.O.S. Pledge (2010), for example, in which, like the Pledge of Allegiance, spectators pledge to take responsibility for environmental stewardship. These are a kind of ritual. In Heal the Man in order to Heal the Land, there’s a room devoted to a shrine and creating a ritual. Are rituals a vital part of art? Is that the performative side of your art?

TT: What we just talked about, the onion and the peeling, is nondual. When you talk about ritual, it is duality, so you associate yourself and the body. You are the body: so I want to heal the body. We live in two different kinds of perspectives. So, when you have rituals, it is really powerful because you want to continue to acknowledge that the body is being nourished by the earth, you want to know that we are all connected as one; all the elements, all humans, the plant kingdoms, the mineral kingdoms. You do the ritual with other people, because that’s when rituals are truly created. When you do it yourself, it’s good, but when you do it with a group, it empowers the whole group. Rituals are something in modern society we don’t do anymore, but in traditional society it actually bonds people together. In some way we still do rituals in modern society, but it is not profound, so you want to go more in depth and get more profound, so when people come together you should have a really good experience.

Tattfoo Tan, S.O.S. Pledge, 2010 [photo: Tattfoo Tan; courtesy of the artist]

WC: How do you design a ritual?

TT: One of the main things is that people share something together, so they can introduce who they are—so we have a shared goal, and from that goal we want to introduce an element people can associate with themselves.

WC: I feel like your practice tends to push people away from alienation—it’s interaction with reality and with the physical environment. In Instructional Piece (2009), you created a list of directives, many of which involve either face-to-face contact or speaking to another human being such as calling someone’s phone or asking them a set of questions, such as “What would be your last meal,” or at least interacting with another person by leaving a trace of yourself in a library book or at a specific location. In terms of generating rituals, there are also the shrines you make. You come from a tradition where there were shrines and deities. You talked about not understanding them and people not giving you a good explanation of them when you were young; but did they have a power for you?

TT: What I was intrigued by was that you have so many gods in the house. There’s the main god, then you have the sky god, and then the land god. The sky god is in the front of the house, near the sky, as high as you can, you put an altar there. There’s a land god, right under the main altar; you put it on the floor. Then other gods will be elevated on a platform or a shelf. In the kitchen you have a kitchen god, so that when you cook, everything will be good; you won’t get a stomachache, and there’s plenty of food to eat, prosperity.

WC: How did that become your practice of making shrines?

TT: Every 15 days—every fortnight—usually, there’s a ceremony, you clean and you redecorate [the shrines]. I guess this became something that I looked forward to. There’s food involved, you always put out fruits and dishes at these ceremonies. I loved the decoration—I saw it as an art project. Especially in my tradition; you have these wooden plaques with Chinese words, and then they have these paper origami ears that you put next to the plaques. I still don’t know what it means today, but it looks super cool. I always had fun playing with the origami ears—very tactile—they’re shiny and colorful.

I got to play with fire, because you need to burn gold paper and incense. I was supposed to light it in the house and then run to this furnace way outside the house. It was sort of a mad dash with fire in your hands. That was my childhood: “Light it and run over there and drop it into the furnace!”

Tattfoo Tan, New Earth Alter, 2019 [photo: Tattfoo Tan; courtesy of the artist]

WC: The altar you created for Heal the Man in order to Heal the Land how will that work?

TT: It’s a place of focus. It’s nondenominational. I like the colors of thermal Mylar emergency blankets, so that’s the gold color in the background. I always put some goatskin on the floor—sages in India usually sit on a tiger skin or something—I like the idea of animal skin. The rest of the objects that are there, to the left and right—a talking stick, very useful, so that when I do ceremonies, kids can’t keep talking—they have to pass the talking stick before they can express their feeling and emotion. The other side is a mask that was inspired by the Green Man—it’s a myth, a show of fertility and regeneration in the plant kingdom. There are arrows, because in this particular ceremony I’m propelling you forward: I’m the bow, you’re the arrow, and I’m shooting you out, expanding your horizon, your idea of reality. Sometimes I have ancient grains on the side, used to make patterns or mandalas on the floor.

WC: In the exhibition, and the book you created to accompany it, you distinguish between “divine” and “mystical.” In terms of contact with God, you talk about the artist as a “holy” person versus a “divine” person. You also mention deep sleep as the only place where you can come into contact with the divine. So, what is the difference between “divine” and “mystical,” and what is the deep sleep connection that you’re talking about?

TT: In the nondual philosophy, who you truly are is called Sat-chit-ananda: consciousness-existence-bliss. That’s who you are, but how do we feel that? I can’t feel it. I’m not this entity called Sat-chit-ananda. Apparently we are being masked by illusion: this is called Maya in our daily life. So in order to get rid of Maya and to experience Sat-chit-ananda, [you enter into] deep sleep, when you don’t have emotion, you don’t have perception, you don’t even feel that you have a body, you don’t even remember who you are. You are just conscious. In deep sleep you might say I see nothing because there is nothing for you to reflect, you are there but there’s not reflection, so you don’t know who you are. So that is who you truly are, and that is what they call god. So, god is not the character the Judeo-Christians talk about, which is an all-loving God that has personality and answers your prayers. This Sat-chit-ananda doesn’t answer your prayers. Sat-chit-ananda is emptiness. It is complete nothingness and also full of possibility. And it is supposedly the thing that projects the whole world. We look like different entities and bodies: diverse in multitude, but it’s only one thing that is projecting all these things. That’s why it’s called nondual.

WC: But some people do achieve this?

TT: When they achieve this they will become what is called a Buddha, or the other word is enlightenment. The other [word] people like to use nowadays is … self-realization. Enlightenment has heavy connotations; a lot of people mistake enlightenment for becoming super holy—you’ll have super powers, you won’t do wrong, you’ll be super-peaceful. It’s just a shift of perception: you’re still you, you still have to go to work, pay your taxes, do your laundry, nothing changes, except that how you look at the world is flipped. Five hundred years ago, when [some] people said the sun doesn’t go around the earth, the earth is going around the sun, [other] people didn’t believe it. [Once] you understand it, the view is the same, but your understanding of the perspective is different. What I’m trying to practice personally is having an understanding of that reality of the world and not be controlled by the illusion.

So nothing has changed; you are still you, with all your tendencies. There’s nothing holy about it, it’s just a total change of perception. And then, once you have that total change of perception, you can decide whatever you what to be.