Chase Hall: Sweat Equity

Chase Hall, Hall & Sons Train Company, 2022, acrylic and coffee on cotton canvas, 96 x 72 inches [courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery]

Share:

Chase Hall’s first solo museum exhibition—The Close of Day, at SCAD Museum of Art—brings together works ranging from 2018 to new commissions that respond to the locale, including a 100-year-old self-playing Wurlitzer, which Hall had meticulously restored and installed in a custom-built brick room that echoes the brick of the museum’s historic structure. Hall’s work manifests at the crossroads between histories of labor, materialist poetry, expressions of racial identity—especially the tensions inherent in biracial hybridity—and the intimate human exchanges that occur between viewer and subject. We met in Savannah, GA, on the morning after the exhibition’s opening, to walk through The Close of Day.

Chase Hall, The Close of Day, installation view, 2023 courtesy of the artist and SCAD, Savannah]

Sarah Higgins: I’d love to start by asking you to set the stage a bit and introduce the exhibition we’re standing in.

Chase Hall: Sure. The exhibition’s title, The Close of Day, came from thinking about when you work hard all day, and the sun’s setting, and you’re cooking dinner—what are you thinking about? Who are you becoming through that consistent idea of getting up and giving it your all? Rinse and repeat. For me, this show felt like the close of parts of my earlier practice. I was also thinking about it being my first museum show and an attempt to put brackets on that time.

This piece, Incarceration, Liberation, Perspiration (2023), [which] we start the show with, is my father’s paintbrushes placed next to Jacob Lawrence’s paintbrushes, which are on loan from Dr. Walter Evans—my father’s paintbrushes are on the left. For me it was thinking about them, not only as inspirations for me—like the carrot in front of the horse—but more like a conceptual studio visit. I can see them hanging out and talking about art. The tools of [the two men’s] labor are the brushes. There were also cool dusters my father made, or palette knives made from plastic knives or toothbrushes. This work was also in relationship to Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cube. I was inspired by that piece, and [by] that relationship of what can be contained in these spaces, or what it means to recontextualize objects just by positioning them in proximity to each other. And this was why I wanted to start the show with this gesture, as a curatorial conceit, or [as] a thesis of the show. Between that [work] and the reflection on my own practice, my brushes get involved in there as well.

And then I was thinking a lot about the idea of labor, family, sportsmanship, reconfiguring agency, and thinking about the hero’s journey.

With this piece, A Man and His Land (2022), I was thinking about what it means for this man to sit in front of his barn, on a bench, with this agrarian landscape behind [him] and thinking about the nuance and the relationship of seeing new owners or free centering agency. I put a lot in the negative spaces within the abstraction. So, there’s this H on his hand, this guy sucking on his wrist over here, this hidden face, this headless guy. Lauren [is] my wife’s name, so there’s a lot of Ls or LCs. And then there’s some playing, like the clown squirty flower.

SH: The squirting flower gag, yeah.

Chase Hall, Incarceration, Liberation, Perspiration, Can of Jacob Lawrence’s paint brushes and can of Chase’s Fathers paint brushes, 2023 [courtesy of the artist]

CH: Yeah, exactly. So, using this idea of whiteness as acne, in relationship to biraciality, those zits in the face are where there’s actually nothing painted at all. I’m really interested in this palindromic idea, where the positive creates a negative. I’m always counterbalancing the stroke versus that void. I’m thinking about Black draftsmanship as a conduit into audacious White minimalism—and what does it mean, for my technique, to actually try [to] achieve both of those, as well as for it be autobiographical, or to hint at some of those spaces between such absolute sides of race and identity.

SH: Yeah, the tension between the expressiveness of the mark versus the absence of a mark—

Chase Hall, The Close of Day, installation view, 2023 courtesy of the artist and SCAD, Savannah]

CH: Yeah! For me, that was from thinking about the glitch as this haunting psychosis of the subject. I use that white space as a bit of tension, or a frequency. I think about an oscilloscope by a hospital bed, that lifeline that jumps up and down. And I’m also directly referencing Clyfford Still in that usage as well. And then, I was thinking a lot about how that nothingness can be activated as a conceptual white paint. I was really interested in how, by painting nothing, the cotton becomes activated, and then that cotton space becomes almost like a use of white paint. And in that refusal, the whiteness exists, but it’s actually just points of void, or points that the subject is still developing to become full or thinking about how to become absolute.

SH: Many of your paintings have the look and feel of historical documentation, or they depict a historical moment. They’re offering an image of a known narrative or known figures, but so many others are just regular people, maybe even unnamed or imagined people. But your treatment of them elevates them to the status of a significant historical figure. That gesture really resonates with putting your father’s paintbrushes [alongside] Jacob Lawrence’s paintbrushes. It’s an equating of the unknown with the known, the hero’s journey—of the famous hero—alongside the unknown heroic.

CH: Oftentimes when we create this demigod complex, it devalues other people’s lives. For me, humanism, humanity, looking … people in their eyes, and witnessing body language and character, those are rudimentary ways of connecting and building community. Street photography was my initial engagement with art, and I’ve always considered what it means to have a subject trust you, and the responsibility to care for them in the best way, as well. I was walking 10 miles a day in New York—for 10 years—and seeing a bunch of people and having these moments of the reciprocity of the eye line. And I remember closing my eyes and, at night, seeing a bunch of people I had run into or spoken to, and I think it has synthesized into a relationship to archetypes.

And what does it mean to be a father? What does it mean to be a son, to be owning land, to be cooking? And I try and hide, and showcase, and live vicariously through that attempt of everyone giving life their best shot. I think that feeling, and that attempt of sleeping well at night, stems from the close-of-day idea, but it also relates to someone trying their best.

And even within the formidable stoicism that I’m painting, those voids and that emptiness are really about the psychosis—you see it in the tension points of the knuckle, the knees the eye, the nose, the mouth. I always leave white these points of tension, a “white knuckling” idea.

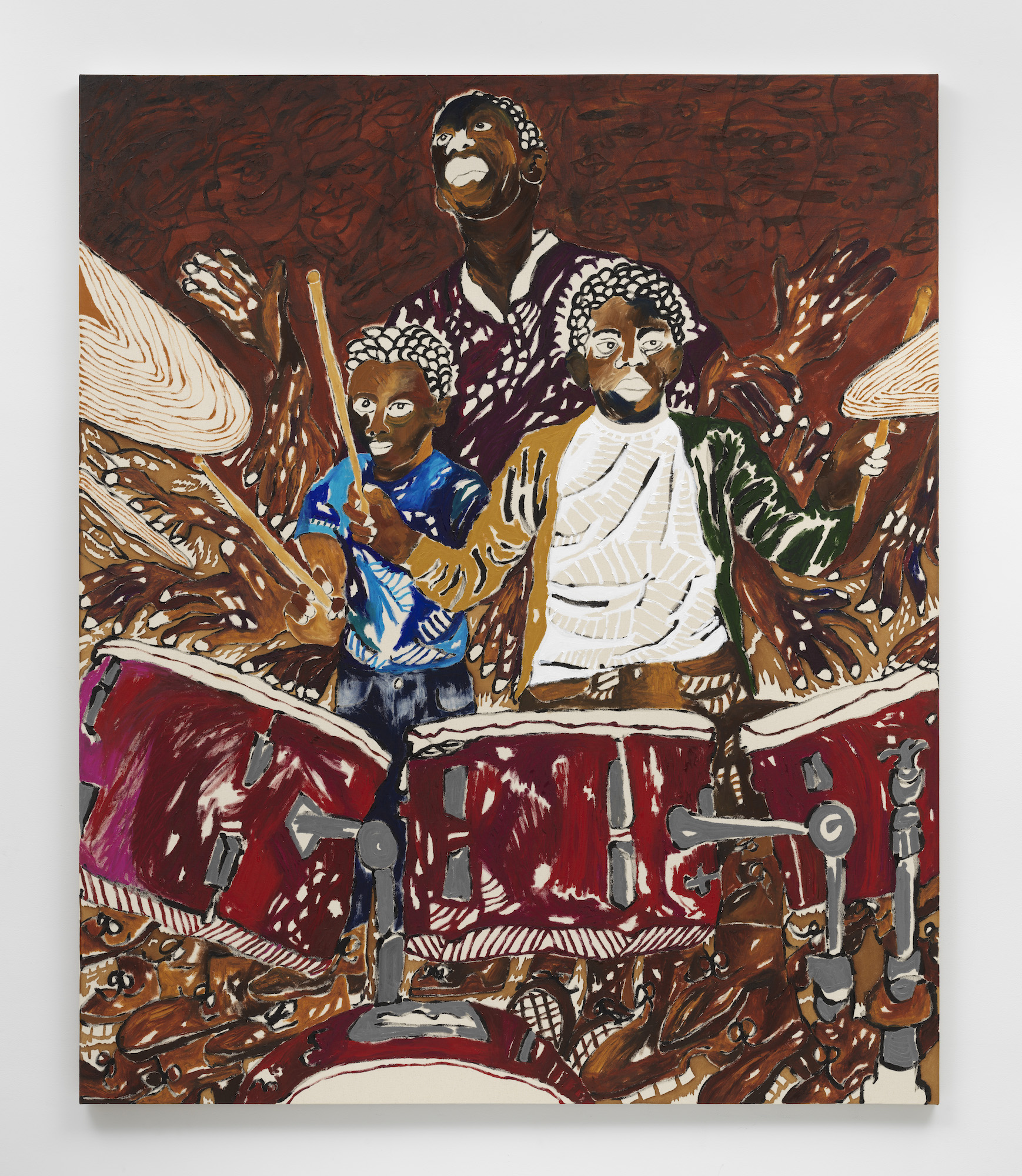

Chase Hall, The Family Was All Around Me, 2022, acrylic and coffee on cotton canvas, 72” x 60” [Photo: Dario Lasagni, courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery]

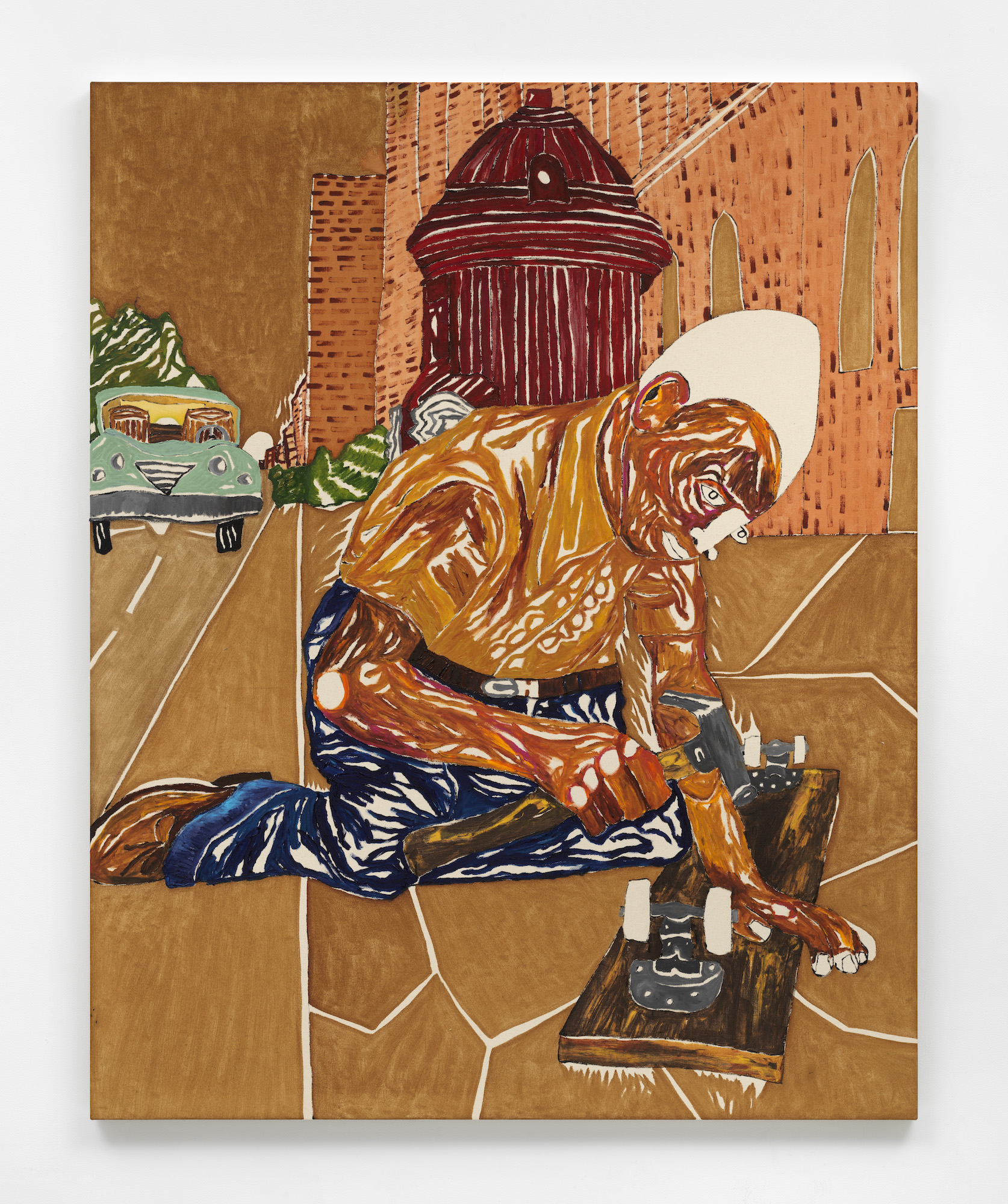

Chase Hall, Setting Up, 2022, acrylic and coffee on cotton canvas, 60” x 48” [Photo: Dario Lasagni, courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery]

SH: That tension also translates into the viewing experience. Even when they’re somewhat at rest, your subjects feel active, coiled. Your work demonstrates so much care and attention to questions about what it is to make an image of a person. The elevation that happens there, but also the violence that can happen. Like how, in street photography, there’s a way that you’re taking someone unawares and making them iconic.

CH: Totally.

SH: To do it conscientiously, you really have to grapple with that tension. How have you tackled those questions in your practice?

CH: One hundred percent. I think for me that was a big part of the pivot from photography into painting, because I was able to understand what I do in my practice for me versus what I make in my practice that goes out, [into] the world, and I think those are very separate. Photography was this initial meat-and-potatoes way of just engaging with the world, but I started to feel those moments when the images were lacking context, or maybe even risking exploitation.

The camera was always a tool to go out in the world and look closely, and I’ve realized that, in a way, it’s almost like a magnet or a compass. I still take photos every day. I have my camera on me. It’s become something more personal—a way to always think about portraiture: to document and to show love.

The camera viewfinder is exactly how I think about the canvas—the way the light hits the subject, I learned from spot metering black-and-white film. How people take up the frame in a photo, that is how I think about people taking up the composition in a painting. That relationship is historical, but it also creates a space where your ideas, or paints, can stroke differently. So, for me, the camera has been a way for me to keep a sense of light and dark shadows, and overexposure, underexposure. Then I allow myself to break those boundaries through the more painterly ideas, the abstract ideas.

SH: Do you see your continued photography practice as a kind of sketchbook?

CH: Yeah—or as tests for drawings. I oftentimes draw straight onto the canvas and start painting immediately. I haven’t thought about it like that, but in a way photography is definitely like a journal or a diary, as something I can look back on for the posture, or the eye line, or this story, or this person. But it’s not so much like I’m making a painting of that person.

SH: It’s such an important distinction to make, the transition you describe between modes of image making—to embrace ways of making that are really just for you—for your own research and [to] draw distinctions between how different processes can serve the work.

CH: Totally. They don’t have to go out in the world. I have thousands and thousands of negatives that have helped me understand humanity, and helped me understand light, and helped me understand what is possible through engaging with others, and that has allowed me to understand the bucket I flip those things into through painting. But they’re very aligned in my head. It’s this kind of public and private space that allows for trust in the subject. Ideally, I’ll be able to just continue to learn and comprehend those people [who] allowed me to see the world in a more beautiful light.

SH: Are there paintings in this exhibition that are particularly tied to this show, or to the museum space?

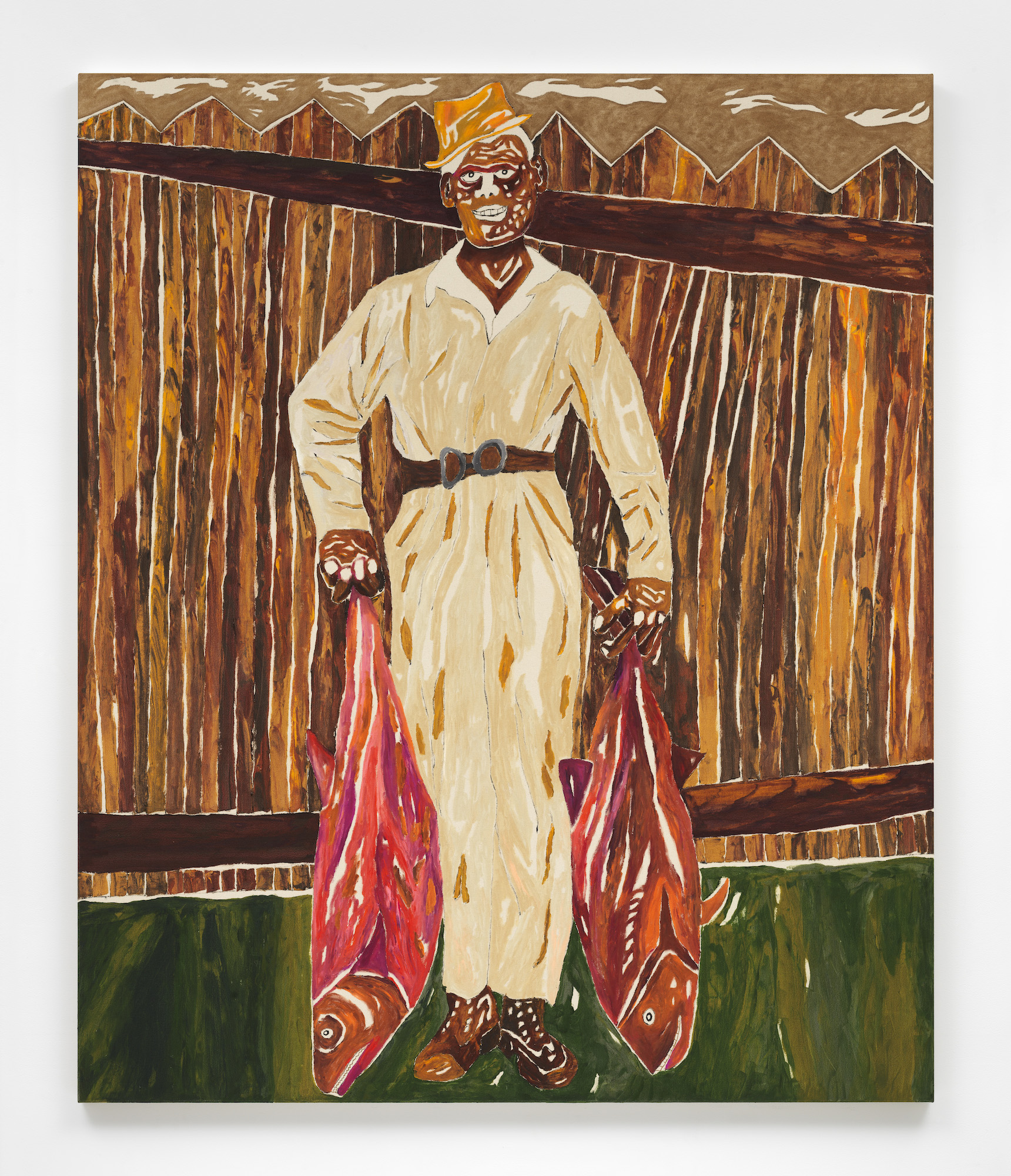

Chase Hall, Everybody Eats, 2022, acrylic and coffee on cotton canvas, 72” x 60” [Photo: Dario Lasagni, courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery]

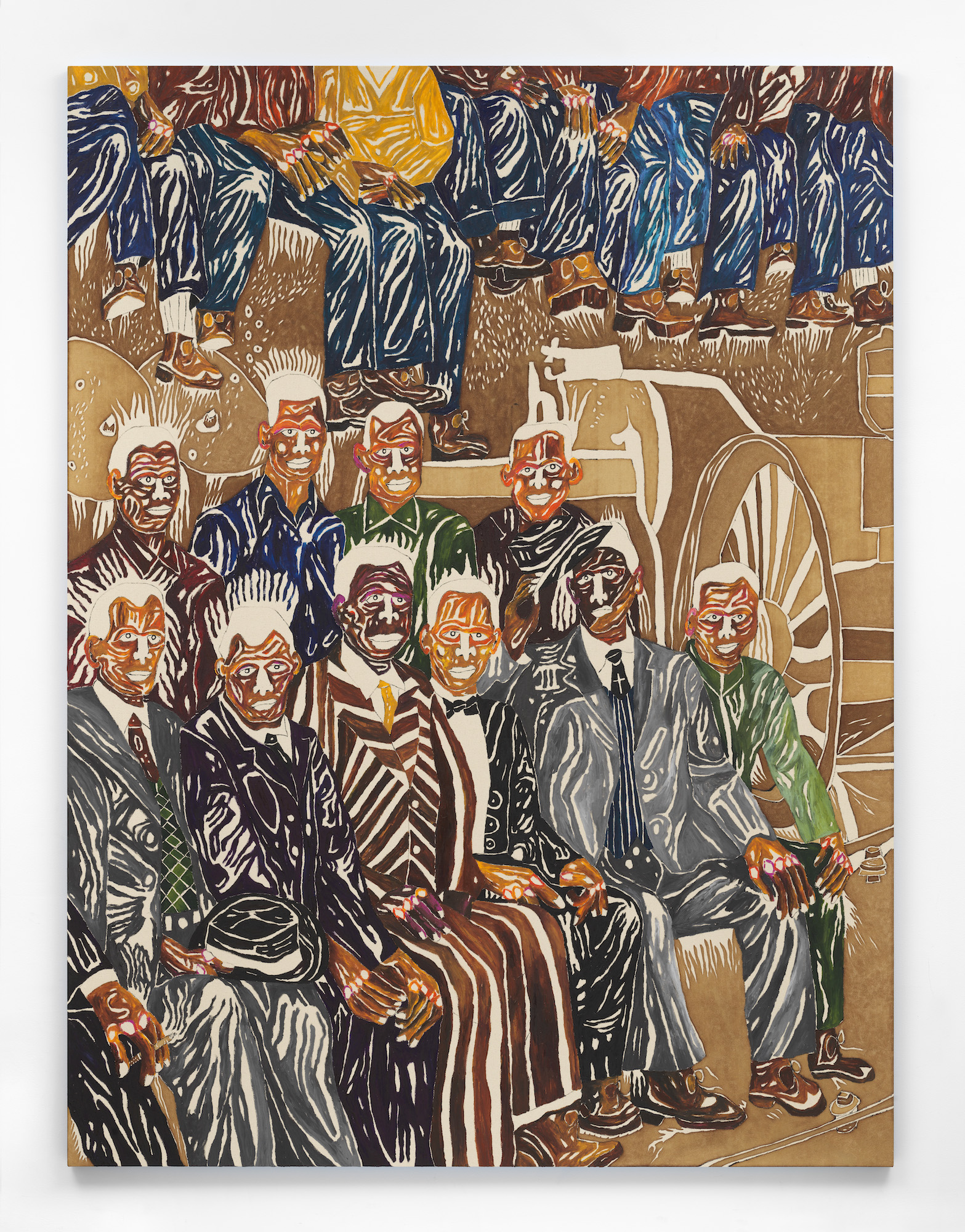

CH: Yes, this painting was the last painting that I made for the show. It’s titled Hall & Sons Train Company. I was really thinking about the relationship to SCAD Museum of Art’s building having been a railroad station, as well as the brick it’s built from being Savannah gray brick, which is historical and aligned with the histories I’m trying to recenter and understand the importance of. This painting was thinking about ownership, equity, and a Black-owned business—one that then has this lineage of cousins and brothers, and the American dream I’ve seen so much through the lens of whiteness through entertainment and movies. It’s [the story of] the lumber mill, and who gets it after the dad dies, and these ideas of business and generational wealth. So, I was interested in the question: If this railroad station was owned by the people who built it, what would it look like today? What would it have done for the generations to come?

There was a lot of hidden gesturing in this painting that allowed me to showcase everyone’s individual personality, as well. This was an important piece for me. My mom’s name was Suzanne, and on this cigarette [points to the canvas] there’s a CH, so this conceptual nod to my mom holding me, as a cigarette, is intimacy. She’s a big smoker, so it’s reminiscent of her. In those moments of hiding things—there is the LCR again, for Lauren Chase Rodriguez, which is my wife’s last name, Rodriguez, between these bones, the C in the bone. I also reference my great Dane, who’s up there.

There are also notions of Christianity, with the cross and Jesus in here—a religious take on how people find reasons to dedicate themselves. There are hidden faces in the shirts, and the way the dreadlocks go in and out of the boot drip—I think about that drip as sweat equity, essentially—when you get wrung out, and everyone’s like, “Jump harder, and faster, and run longer, and be early, and be there last.” It’s this notion of working twice as hard that I think about as drip—when you ring out a washcloth and that sweat drips out. That cotton space as dreadlocks is a way to talk about black hair in general, whether it’s bald, or smaller twists, or the dreadlocks that come down like this Einstein-esque shape.

I’m brewing the coffee [for use as a pigment] myself. To create a dark brown, I’m using a very fine coffee. To create a light brown, I’m using a very coarse coffee. And then the techniques I use to brew them are a stovetop espresso machine and Chemex. I’ve developed about 26 different browns out of a single bean, and I’m able to use a tonal chart to remind myself how I achieved those looks. There’s an alchemy in that, and then there’s this abstraction that comes alive in the painting. I don’t plan out where this person’s going to be, or seeing my mom in the hand. It just happens as I’m painting. It’s like this marble starts showing itself, metaphorically, and I’m just chiseling away at that, and listening to that gut feeling. Like free jazz, or ciphering and freestyle rap, there’s a punch and a counterpunch, and you’re always finding that positive and negative while letting that psychosis run free in the trust of your painting and the trust of color and subjectivity.

SH: I had thought of the coffee so much as a way to make a pigment, but it’s also a symbol of labor and exhaustion, and the workaday thing. There’s a subtextual question posed, maybe, that is—besides coffee, what keeps people going?

CH: Totally. With the coffee, there’s a relationship to seeds coming from Africa, being put on a boat, being exploited through machines that demanded the most out of them. I see that a lot in the Black experience. And I think there is this notion that paint wants to react for you. It’s a very calm substance, whereas coffee is the exact opposite. As soon as I pour it, it spreads. It’s boiling hot, and if I don’t do it immediately, there’ll be patches and inconsistencies in the tones. So the relationship to speed, trusting your gut, and the intuition really does have to happen immediately. I can’t have the areas of tone cross because then they’ll start bleeding in and out of each other. There’s timing, there’s speed, and then there’s the ways in which you actually have to trust your stroke.

For this painting, I had to paint on a ladder laid flat, and hang over the painting, because you have to do the coffee flat. I couldn’t have a drip on the figures. So, I have two ladders; I’m hanging over the painting, like a scaffolding man.

Chase Hall, Thelonious Number, 2018 – 2019, acrylic and coffee on canvas, 96 x 48 inches courtesy of the artist and Lois Plehn, New York]

SH: You’ve spoken before about the unmarked canvas becoming a metaphor for whiteness. There’s a kind of unseen performative element in your physical struggle to create these images around—to negotiate and have to struggle around—those spaces that are representing whiteness. Is that a way that the process relates to the concept?

CH: Yeah, this was the idea. Painting has been about layering and covering the canvas, so for me, the refusal comes in leaving those empty spaces, how the strokes and the marks I make have to be sure, and how I have to trust the feeling because there isn’t much room to cover up. In that space of glitch, or that haunting void, it was, like, that was from Lucio Fontana, that was from Clyfford Still, that was from Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner.

SH: You’re so great about naming your influences, or references, about naming all of the places that you’re drawing ideas and practices from. I don’t recall you ever mentioning Hale Woodruff, but I want to speak his name because there’s such a resonance there for me in your compositions.

CH: Oh, wow, I see that completely.

SH: Oh, and someone who I’m just learning about, Bruce Onobrakpeya!

CH: Oh, I’m not familiar with him.

SH: He’s a Nigerian modernist whose work I’ve only recently been introduced to. But I could see kinship with your work—in the palette and compositions, in how narrative is expressed, and the tension. I think you’d like him! He’s having his first museum solo exhibition in the US at the High Museum in April.

CH: I would love to learn more about him.

SH: Can you speak a bit about the restored Wurlitzer that occupies its own chapel-like space? I understand that it will play twice a day, at set times.

Chase Hall, The Close of Day, installation view, 2023 courtesy of the artist and SCAD, Savannah]

CH: So, the Wurlitzer was built on July 7th, 1923. Its hundred-year birthday will be July 7th, 2023. We chose the brick to be in relationship with the Savannah gray brick. The pews in that room that we built—they were built by Black hands at a Black church in 1888, in North Carolina. When the Wurlitzer’s performing, which happens twice a day, it’s the idea of [it being] the great-great-grandfather of the iPod, almost. It’s posing a question about how this early form of AI, almost, performs a kind of labor devoid of humanity.

SH: Automation versus the soul of music making?

CH: Yeah, exactly. The humanity and the spirit versus AI, and we’re still facing those questions today.

Chase Hall, Hall & Sons Train Company, 2022, acrylic and coffee on cotton canvas, 96 x 72 inches [courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery]

Sarah Higgins is editor + artistic director of Art Papers.