Siegfried Kühl

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS January/February 1991, Vol. 15, issue 1.

Siegfried Kühl, a sculptor working and living in Berlin, was born there in 1929 and studied at the Berlin Art Academy from 1945- 1951. During this time that he met and befriended the dadaist Hannah Höch; they remained in close contact until her death in 1978. Partly because of their close relationship, Kühl was commissioned to build the towering Höch Memorial which faces the Tegeler See and overlooks the setting where they spent many hours skating on the frozen lake in winters and walking along its tree lined shore in summers. The winged bronze figure of this powerful and inspiring monument appears curiously alive.

In December of 1989, Berlin was celebrating the 100th birthday of Hannah Höch with several exhibitions of her work, including a major one at the Martin Gropius Building, where her works were shown with documents from her life, included the works of some of her friends, among them Kurt Schwitters, Jean Arp, and Theo Van Doesburg.

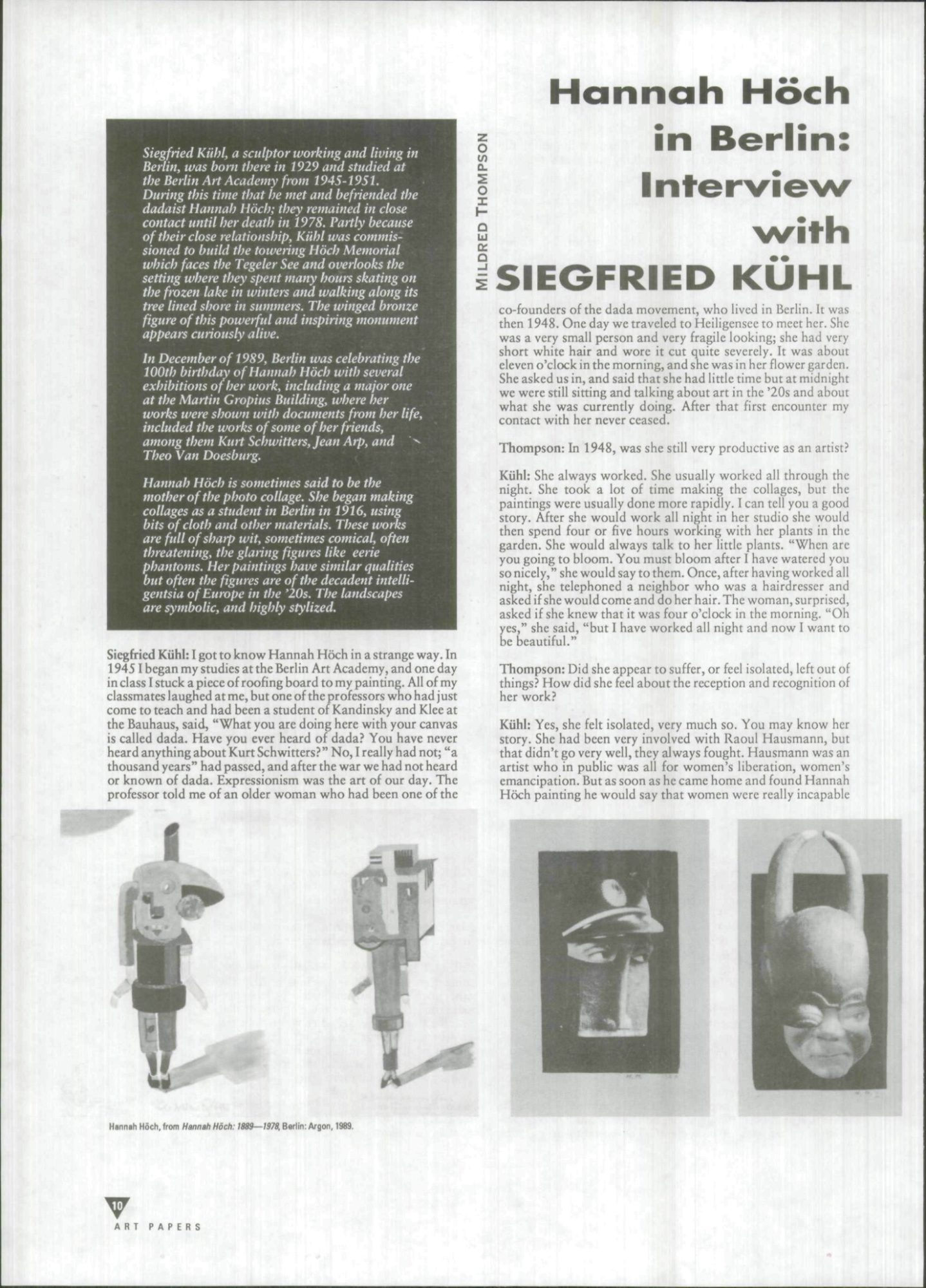

Hannah Höch is sometimes said to be the mother of the photo collage. She began making collages as a student in Berlin in 1916, using bits of cloth and other materials. These works are full of sharp wit, sometimes comical, often threatening, the glaring figures like eerie phantoms. Her paintings have similar qualities but often the figures are of the decadent intelligentsia of Europe in the ’20s. The landscapes are symbolic, and highly stylized.

Siegfried Kühl: I got to know Hannah Höch in a strange way. In 1945 I began my studies at the Berlin Art Academy, and one day in class I stuck a piece of roofing board to my painting. All of my classmates laughed at me, but one of the professors who had just come to teach and had been a student of Kandinsky and Klee at the Bauhaus, said, “What you are doing here with your canvas is called dada. Have you ever heard of dada? You have never heard anything about Kurt Schwitters?” No, I really had not; “a thousand years” had passed, and after the war we had not heard or known of dada. Expressionism was the art of our day. The professor told me of an older woman who had been one of the co-founders of the dada movement, who lived in Berlin. It was then 1948. One day we traveled to Heiligensee to meet her. She was a very small person and very fragile looking; she had very short white hair and wore it cut quite severely. It was about eleven o’clock in the morning, and she was in her flower garden. She asked us in, and said that she had little time but at midnight we were still sitting and talking about art in the ’20s and about what she was currently doing. After that first encounter my contact with her never ceased.

Mildred Thompson: In 1948, was she still very productive as an artist?

Kühl: She always worked. She usually worked all through the night. She took a lot of time making the collages, but the paintings were usually done more rapidly. I can tell you a good story. After she would work all night in her studio she would then spend four or five hours working with her plants in the garden. She would always talk to her little plants. “When are you going to bloom. You must bloom after I have watered you so nicely,” she would say to them. Once, after having worked all night, she telephoned a neighbor who was a hairdresser and asked if she would come and do her hair. The woman, surprised, asked if she knew that it was four o’clock in the morning. “Oh yes,” she said, “but I have worked all night and now I want to be beautiful.”

Thompson: Did she appear to suffer, or feel isolated, left out of things? How did she feel about the reception and recognition of her work?

Kühl: Yes, she felt isolated, very much so. You may know her story. She had been very involved with Raoul Hausmann, but that didn’t go very well, they always fought. Hausmann was an artist who in public was all for women’s liberation, women’s emancipation. But as soon as he came home and found Hannah Höch painting he would say that women were really incapable of painting. She told me about how once when they were fighting, he said women should be forbidden to paint and he grabbed her and locked her in the attic. She climbed down to a neighbor’s balcony and back into her studio and when Hausmann found her there she was painting. They separated after that. People always say that Hannah Höch was not recognized. This is not true. There were always people who appreciated her. There was Kurt Schwitters, and his family, and Mondrian, and Van Doesburg, as well. In 1932 she was offered an exhibition at the Bauhaus, but the show never materialized because the Nazis were already on the town council and forbade it, and later the Bauhaus was closed.

Thompson: Did Höch stay in Germany during the war?

Kühl: During the war she, unlike her companions, stayed in Germany. Schwitters went to Norway and later to England. Hausmann too went abroad. Höch went to Holland for a short time but she returned and lived in Friedenau. On Hitler’s birthday everyone was supposed to put out the Nazi flag. Hannah Höch would not fly the flag and this caused the neighbors to talk. They asked her why she didn’t hang the flag, and she claimed she had no flag. Once one of the neighbors brought her a flag; she never flew it and somehow was able to get by. She moved from Friedenau to Heiligensee and married, I suppose to be able to change her name and to hide. She never spoke about this marriage. In Heiligensee they probably didn’t know of her as the Cultural Bolshevist, as she was referred to by the Nazis. She lived in a little house for transport workers at a former military airport; the place was grotesque but she and her husband, an amateur pianist, lived there and entertained with his music. This marriage didn’t last very long either and she never said anything about it, or her husband.

Thompson: How was she able to support herself during this time in hiding?

Kühl: I never quite knew how she managed financially during the “1000 Years,” or if after the war she received some sort of social security. I do know that she would sell flowers and little bouquets from her garden at the cemetery. No one among her neighbors knew that she was an artist. She had shut herself off completely, and lived among her flowers; her place

was hidden from view by the vines that grew everywhere. A sign on her place read “Roseneck” (roses corner), and people thought she was some kind of rose cultivator. She was a very intelligent woman, well-read with an extensive library. She was interested in the sciences and technology and kept abreast with the newest research. In her garden, on an electrical box she wrote, “Today the first man landed on the moon.”

Thompson: Did she exhibit regularly after the war?

Kühl: She had the first exhibition at the beginning of the sixties, at Gallery Nierendorf and in the Graphothek, which I founded. It was a beautiful exhibition and all of the work was unknown by the public.

Thompson: Were the new collages in the exhibition?

Kühl: No, there were only watercolors and oils, but she never stopped making the collages. I would sometimes watch her doing them from her garden window. If she did not notice me, I would not disturb her. She had envelopes and folders filled with magazine clippings, assorted according to color, never by subject. They were cut with the scissors very precisely, then she would begin to assemble them by pushing them about the page with her scissors and when she was satisfied with the composition she would glue them down meticulously. Sometimes when she was finished with a work we would brainstorm about a title. She always liked titles that were a little bit vague.

Thompson: Hannah Höch always had her circle of friends who knew her and the importance of her work, but her name is not always mentioned when one reads or speaks of dada. Arp, Schwitters, Huelsenbeck, Tzara, for example, are always the names we associate with dada.

Kühl: Yes, but the fact is that she was not interested in that. She stood in the background not because she was a woman, but because of the times. After 1945, Expressionism was in the foreground in Berlin. Carl Hofer was the director at the Academy and an expressionist in his own way. He appointed Karl Schmitt-Rottluff, Max Pechstein and other die Brücke artists and it is known that the expressionists and the dadaists were never on good terms. The expressionists thought the dadaists were crackpots and by their actions and attitudes they gave reason for their sincerity to be doubted. “Art is dead.” “There is no art, only world.” Those were some of their slogans. They were an anti-art movement while the expressionists considered art in the spirit of the medieval tradition; art was holy to them. They were at extreme opposites, and that is why we never heard anything about the dadaists at the academy or saw their works in museums. We were taught everything, Rembrandt, Goya, everything right up to Max Beckmann. And then dada began to come over from America. Of course Beuys was already around, but nobody talked of him in the early fifties. Only after Rauschenberg and others from the Pollock circle in New York had the grand dada exhibitions here did the people remember dada and realize that some of the old artists should still be around. Schwitters was already dead, but Hausmann and Hannah Höch were still alive. It was then that Hannah Höch was again established as an important artist and hailed as one of the co-founders of the dada movement. But she didn’t care anything about that. She was already involved in her new work, and did not want to be locked in the dadaist role. She once even went so far as to say, “Dada kotzt mich an.” (Dada makes me puke.) For her the attention was too late and she had moved on to new and other means of expression.