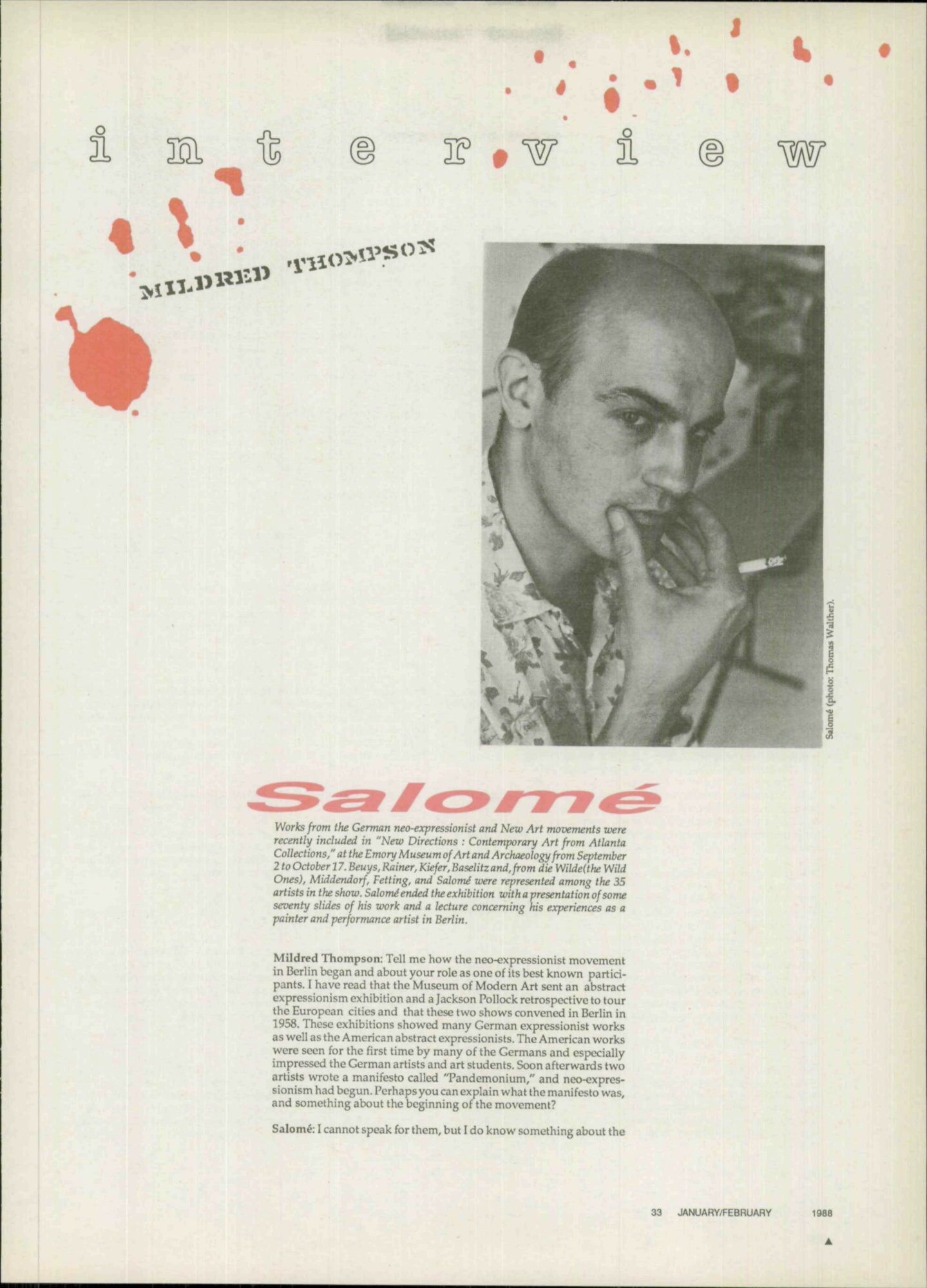

Salomé

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS January/February 1988, Vol. 12, issue 1.

Works from the German neo-expressionist and New Art movements were recently included in “New Directions: Contemporary Art from Atlanta Collections,” at the Emory Museum of Art and Archaeology from September 2 to October 17. Beuys, Rainer, Kiefer, Baselitz and, from die Wilde (the Wild Ones), Middendorf, Fetting, and Salomé were represented among the 35 artists in the show. Salomé ended the exhibition with a presentation of some seventy slides of his work and a lecture concerning his experiences as a painter and performance artist in Berlin.

Mildred Thompson: Tell me how the neo-expressionist movement in Berlin began and about your role as one of its best known participants. I have read that the Museum of Modern Art sent an abstract expressionism exhibition and a Jackson Pollock retrospective to tour the European cities and that those two shows convened in Berlin in 1958. Those exhibitions showed many German expressionist works as well as the American abstract expressionists. The American works were seen for the first time by many of the Germans and especially impressed the German artists and art students. Soon afterwards two artists wrote a manifesto called “Pandemonium,” and neo-expressionism had begun. Perhaps you can explain what the manifesto was and something about the beginning of the movement?

Salomé: I cannot speak for them, but I do know something about the generation that came after the manifesto. I got to know K.H.Hodicke, who was involved with a group of painters called “Grossgorschen,” after the student revolution, who felt that it was absolutely necessary to create their own new approach to German art, by painting freely and vividly, by staging questions to society, by transforming the taste of society. So it was in the tradition of the student revolution. It was very influential. But before “Pandemonium” was written, there were already teachers like Fred Teiler in Berlin, who taught this generation about painting. Like Jackson Pollock, Teiler always painted with his canvas on the floor and was dripping his paint across the surface. So, after the war there was already the bridge for the continuation of the expressionistic style which came from the 1930s. So, “Pandemonium” was just a logical follower in this whole line that developed and dominated the art scene in Germany. I came along when all of these guys were already teaching. They had already gotten their feedback from the manifesto. It looked like they had not been very successful with it, that art could not take up the imagery of Expressionism then, because Social Realism was very stong. It began to move in the ’80s when another strong youth movement, Punk Rock, came up. The full Punk era, with the Sex Pistols, the Nonas, standing up against your father, who was about the age of my teacher—there was a kind of revolution going on in the arts, and because the movement was so strong, with new music, new imagery, new painting styles even further advanced than probably Hoettiger or Baselitz.

It was a clearer, more useful thing. I think that this is all concentrated in what is now called neo-expressionism. It reaches from the abstract to the nowadays. And right now we are seeing a new line of figurative work, the so-called Braunschweig School or “The Cement Painters,” like Schendler or Peter Candle from England. Their work is based on the heavy painting of the figure, and the figuration looks like a ton of stone. So there really is a continuity in German art.

MT: Do you think that a movement could have come about in other places in Germany than Berlin? Do you not feel that the movement is peculiar to Berlin, because of its story?

S: Yes, because Berlin was isolated culturally. Even if there were artists from other countries coming in, it was still isolated from the map of world art. It was a blank spot. The Berlin wall, the youth movement, the Punks, and the groups from Gay to Women’s liberation and other minorities…this all made a new situation. The political situation was really fixed; we are this island with a wall and barbed wire all around us, there is this certain feeling that is not transferable to any other city. Berlin has a population of very old and very young people. There is nothing in the middle that really represents a society, so life in Berlin is very different. There is a so-called Left or underground, the Green Party is very active, and so on, and this all contributes to Berlin becoming a new art center.

MT: These movements are helping Berlin to reclaim what Berlin had been before, a world center for the arts. Perhaps you can tell us something about what is going on in the other arts as well, and about your role in the performing arts, and your work with the singer Nina Hagen.

S: Berlin was traditionally the artist city in Germany. When I came there in 1974, it was still a big student city, and by 1979 it got a kind of international flair with young people coming from all over Europe. There were a lot of heavy off-scene cultural events going on; in a week you could see five different performances. This was unusual for a German city, this kind of thing was not going on in Cologne, for example, although more art is sold in Cologne. I started doing performances in public. I did a 12 hour performance in a gallery window I had transformed into a box. In it was a delicate object and the object was myself. I was a still standing object and every hour 1 changed positions. We were experimenting with our bodies; these performances were severe and dangerous.

MT: Severe and dangerous in what way?

S: For example, Abramovic and Ulay, who did performances where they were banging their bodies against walls, or knitting their hair together for hours. The 12 hour performance I did was just another of these events. We did a movie, Ice Skating Queens, crazy things with action and ridiculous costumes. A friend, Allute, did things where she locked herself in a room and performed all night long. There were big Punk rock places, where the music was really free and powerful, the messages political: freedom for everybody, aggression against everything that has to do with pressure on people. Nina Hagen had just been thrown out of East Berlin because she had caused too much trouble. She had been too Western oriented. Her first album in the West was highly successful because her voice is incredible, she is able to sing coloratura to comic strips. We liked each other as soon as we met, because we were both crazy. She knew of the wild things I had done. I did strip tease dancing in public bars, where everybody and anybody could go in, from grandmother to the child. So, Nina Hagen and I came together in Berlin, and often went out together and had fun singing in the streets and in the subways. Everybody knew her and her records were selling in the hundred thousands. She liked the performances that I did. So when she came out with her second album she asked if we would be her front band. I for the first time sang before ten thousand people; it was a great success and then we made records and we were all very happy.

MT: Did the city do anything to help to promote and sponsor these events?

S: Berlin has a tradition of sponsoring culture. Right now I think that the city spends about two hundred million marks on the arts. This is for all of the arts, and this is one of the attractions for the artist. Berlin is really a cultural city; it has always been a showcase for the West to demonstrate what the West can do, and what the East is not. Berliners say, “We are the fat eye in the Red soup.” A lot of people travel to Berlin to see what politics is able to do, no matter who did what, to see and experience how political life influences all of us.

MT: Have you ever had contact with DAAD (Deutsche Akademischer Austauschdienst), the cultural exchange program designed for the artist?

S: Yes, I got that. Things began move furiously after I, with my friends Middendorf, Fetting and Zimmer had shown all over the world. We were, immediately, a big success around the world; the city felt kind of bad that something was happening right under their eyes, and they wanted it to have a political effect. I didn’t even apply for it. They gave it to me, as if to say, “We’ll give this to you, please take it. Go to New York and represent us, say good things about Berlin.” I had already been in New York, in 1978. I performed on West Broadway in the streets because I was a student and had run out of money, but I only made a dollar and fifty. So I went to New York but had so much to do I couldn’t stay. I traveled all over the world. Then two years later, I decided to move to New York, because Berlin oppressed me too much. Everybody knew me, even on the bus, because I had been invited to all the talk shows on TV. Living became too public.

MT: Were you and your friends, Zimmer, Middendorf, and Fetting— “Die Wilde”—in any way, at all prepared for this kind of instant success?

S: No, no not at all. Because for us it was a statement we wanted to do: “Look, here is good art. Come look at it, let’s hear how you react.” We didn’t think that it would happen, but it really happened overnight. The telephones rang and rang and rang, we were invited to show everywhere, all over the world.

MT: When and what was this exhibition, was it in your gallery at Moritzplatz?

S: This was our first appearance at Haus am Waldsee in Berlin. At our gallery we only showed one artist a month. At Haus am Waldsee we were just the four of us. Haus am Waldsee was a place where all of the great artists showed, Rauschenberg, Warhol, all of the greats. They made a catalogue for us, it was our first catalog. We were proud, we just wanted to show off and people liked it. We just wanted to show off, we never thought that it would be any kind of great success.

MT: How did that kind of success affect the group, and you individually? We are all conditioned to accept and deal with failure, but nowhere are we taught how to deal with success.

S: We stayed close for the next two years, just for the support. Then everyone got a feeling of what it was to work in such an enormous public. After everyone felt strong in himself, the group broke up. We see each other at shows and we talk to each other, but it’s not like inviting somebody over to your studio to see your work. There are the museum shows where we all meet and that is where we see each other’s work. Everybody now has a big private life too.

MT: How did you get the name, “The Wild Ones,” did you name yourselves, or was that the invention of some critic?

S: We called our show, “Heftiger Malerei.” There is not a real translation in English, it means something like violent painting, and the first writer about the show, Hans Bischoff from Berlin, titled the show and us, “Die Wilde” and from then on, everyone used it.

MT: Do you think that ‘The Violent Ones” would have said more about who and what you thought of yourselves?

S: We thought that the paintings were really violent, whatever that means, and that “Wild” was too mellow. Perhaps viewers could not associate with the word violent and felt more comfortable with “The Wild Ones.” I don’t care anything about titles anyway; sometimes I call my shows “Berliner Luft,” or “Winter” or “Frauen in Deutsch- land,” just to avoid using “isms.”

MT: Your work has been described as portraying a conflict between homosexuality and convention. I questioned the word “conflict:” does it mean a personal conflict or a social one?

S: I don’t know about the word “conflict,” but I know that there is a big dilemma. Certain people still have no respect for other people’s religions, other people’s races, or other people’s private lives. I think it is time for every one to stand up on his own because there is no such thing as a big majority to say, “This is good, and this is bad.” Everybody has to work his own way to freedom, and has to make freedom for others. This is freedom for me. My work is about that. It is just natural as I am in a conflicting group and a part of a minority. Of course my work relates to that. Everybody has to not just fight but also educate, because the majority always says, “Oh, these are the crazy ones, and every thing that goes wrong we can put it on them so we don’t have to question ourselves.”

MT: How has living in California affected your work?

S: It gives me a sense of lightheartedness. There is a serious part of my work, where I feel I need my Berlin walls. There is another where I try to paint the fun in life, and the California light, the people, the landscape, the ocean definitely contribute to this. You cannot always paint this one strong painting that says all.

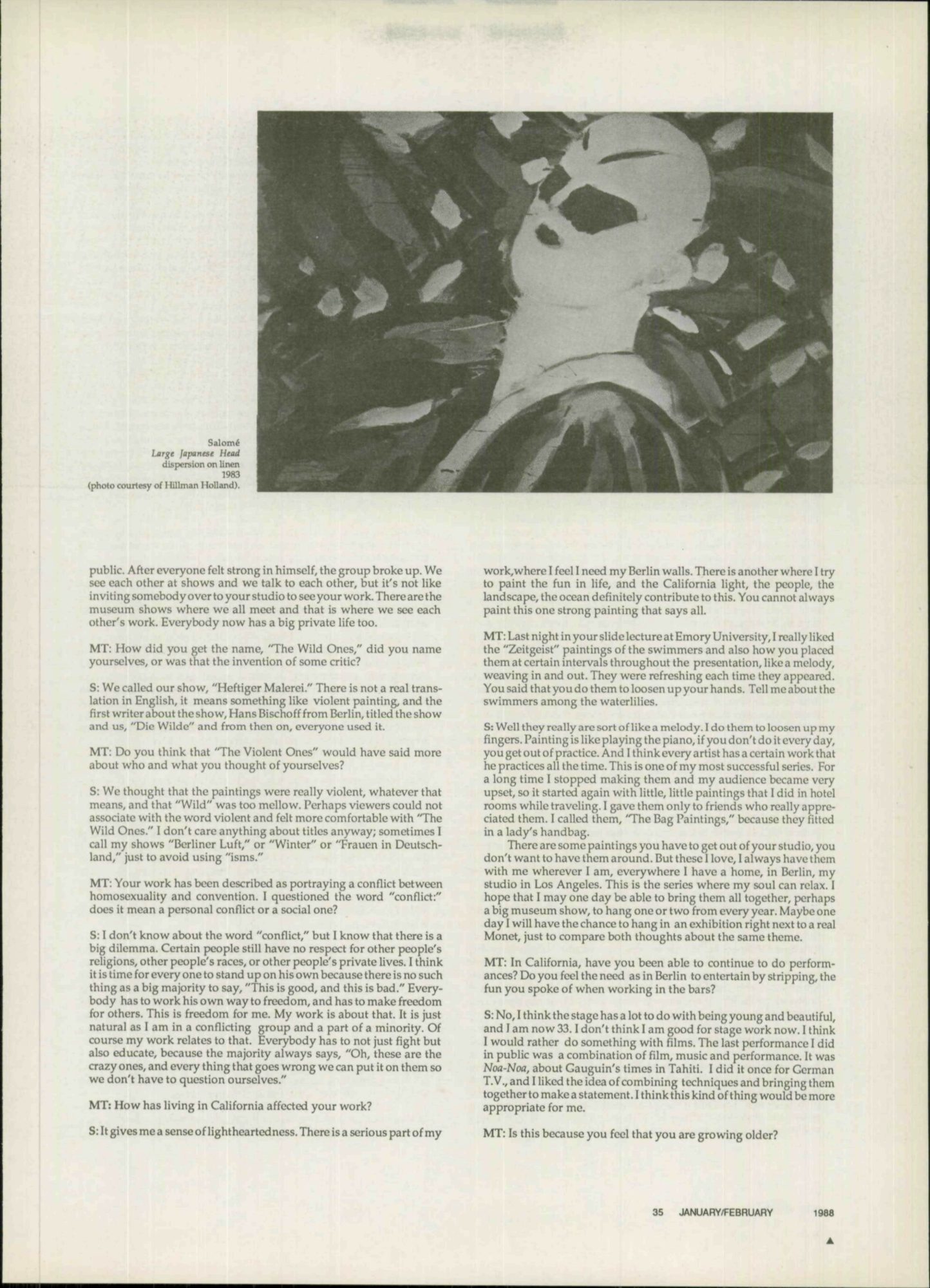

MT: Last night in your slide lecture at Emory University, I really liked the “Zeitgeist” paintings of the swimmers and also how you placed them at certain intervals throughout the presentation, like a melody, weaving in and out. They were refreshing each time they appeared. You said that you do them to loosen up your hands. Tell me about the swimmers among the waterlilies.

S: Well they really are sort of like a melody. I do them to loosen up my fingers. Painting is like playing the piano, if you don’t do it every day, you get out of practice. And I think every artist has a certain work that he practices all the time. This is one of my most successful series. For a long time I stopped making them and my audience became very upset, so it started again with little, little paintings that I did in hotel rooms while traveling. I gave them only to friends who really appreciated them. I called them, ‘The Bag Paintings,” because they fitted in a lady’s handbag. There are some paintings you have to get out of your studio, you don’t want to have them around. But these I love, I always have them with me wherever I am, everywhere 1 have a home, in Berlin, my studio in Los Angeles. This is the series where my soul can relax. I hope that I may one day be able to bring them all together, perhaps a big museum show, to hang one or two from every year. Maybe one day I will have the chance to hang in an exhibition right next to a real Monet, just to compare both thoughts about the same theme.

MT: In California, have you been able to continue to do performances? Do you feel the need as in Berlin to entertain by stripping, the fun you spoke of when working in the bars?

S: No, I think the stage has a lot to do with being young and beautiful, and I am now 33. I don’t think I am good for stage work now. I think I would rather do something with films. The last performance I did in public was a combination of film, music and performance. It was Noa-Noa, about Gauguin’s times in Tahiti. I did it once for German T.V., and I liked the idea of combining techniques and bringing them together to make a statement. I think this kind of thing would be more appropriate for me.

MT: Is this because you feel that you are growing older?

S: Oh yes, and I am really happy about it. Every year counts now. I want to do things that I haven’t done. It is now time to look to fields that will be new for me.

MT: Do you think that the neo-expressionism is also a passage, and that you will move on to other means of expression?

S: I don’t know that. This is something that is in the future. I hope that I let my work develop and not just get caught up in a corner and have it said, ‘This is what he has done his whole life.”

MT: Do you find that to leave a familiar environment for a new one where no one knows you, where everything is new, the customs, the language, the landscape, acts as a cleansing agent for your work, for your being?

S: Oh yes, this is one of the reasons I must live abroad. Things have cooled down a little bit in Berlin now, I can go there and I am pretty much left alone, but living abroad brings a lot of good things with it. Also it gives me a chance to see Germany under a different microscope. It is good to get distance from your country and to see how it is seen from other countries. All of this is why I started my Wagner paintings in New York. I could have a good strong hold of the ideas in New York.

MT: Is there something particular you are trying to point out beyond the music in the Wagner Series? Are you saying something about folk myths in general, or the Hero, or the spirituality in Wagner’s work?

S: First, it is the musicality of the paint which is dictated to me by the music, just giving color to the music and having the colors vibrate. The other thing is the story. It’s like Adam and Eve, it starts and it ends, it starts and it ends: it is a never ending story. I grew up with it. I know of all the negative things that are associated with Wagner, but I also know of the positive things. Painting it is like painting a mirror of Germany, about certain national situations, or states of mind. So these paintings are for me, maybe more abstract, but what German life is about. Some of the paintings are very crude but they are true, like the murdering of the hero. This is also a universal theme. It is wonderful for a painter to have something written for which you can imagine the picture. So it was for me, and it is for me a political statement. They were also hard to paint, like Siegfried getting murdered in Dachau. It is a painful thing to bring it on the canvas, because it is a deep, deep tragedy, so it gave me a great satisfaction to get it off my soul and get it into paint.

MT: We are told that there is a a great sense of spirituality in Wagner’s music, and perhaps he chose those mythological themes because he wanted to make some kind of a spiritual statement. Do you agree with this?

S: Yes, well this whole saga for me is another Bible. It is another historic book from way, way back but it has a universal language and the story of the universe is in it. It may not be a Roman Catholic or a Jewish interpretation but it is like an old religion. So they are in a way religious paintings too.

MT: Are you personally moving toward something of mysticism or the spiritual?

S: Religion for me is something very private. I don’t like the behavior of churches. I think everyone has their own religion, as their own color, their own hair-do, and God is nothing commercial at all. I got out of the church but I still think that there is a God, and there are symbols that make the viewers see that you mean that there is a God. In 1982, I painted crucifixions. My studio was filled with crucified Jesuses. I am, in a way, deeply religious. Recently, I did a painting for a little church in Germany. They had lost a work painted in the 1300s about the life of Jesus, and they asked a lot of prominent artists to repaint it. The little community wasn’t that rich. They sent me a verse from the Bible and asked if I could paint it and I was delighted that a church would ask me to do that. I painted this little painting of how Jesus comes to hell and the devil throws his tongue out and throws a big stone at him and some ghosts are in jail with big flames coming out. I was laughing while I was doing it, but at the end it achieved a religious statement that perhaps comes over to the viewer. So it is all possible. Museums are nowadays like churches, they offer the new religion. We see it in the climbing number of visitors.

MT: In the very beginning, what was the public reaction to your work, especially the subject matter. Were they provoked?

S: Oh yes, some people shouted that they had never seen such shit— asking what this was all about, some people walked out of the gallery saying that they didn’t understand it.

MT: I read something about Georg Baselitz’s paintings The Great Piss Up and The Naked Man, shown first in 1963 in the Werner and Katz gallery. There was a lot of confusion surrounding the show, the paintings were removed from the gallery by the police because they were said to be pure pornography. Can you tell us about this scandal?

S: It was not The Great Piss Up it was my Pink Times. It was in an exhibition in Dusseldorf and some people protested that the gallery was open to the public. They protested because there were erotic scenes in the paintings in which you couldn’t figure out who was doing what to whom. But they all looked very happy, they were all happy faces. I really wanted to paint my version of paradise. I wanted to show how we should all be very close to each other, just like it’s written in the Bible. We are all the same, we should love each other. Then the authorities came and closed the place down, and then only people over 16 years old could come in; the place was declared kind of a porno area. But my lawyers cleared it up, declaring the right and freedom of the arts and saying this work is not what you pigs say it is. Then some lunatic went in and sprayed over the whole painting with black and the painting had to be taken out of the show.

MT: What year was that?

S: It was the International Show in 1984,1 think. It made big waves because it was an assault on the arts. It was not just against my work, they were against Joseph Beuys’ work too. Beuys’ work had to be guarded all the time. After all this there was a trial. The man who defaced Pink Times had to pay only three hundred marks, but the damage was about twenty thousand marks, just to clean this dirty black color from all over the canvas. I have had experiences, a couple of times, where people through their lawyers, tried to have me stopped, to prevent me from showing my nude paintings. I had a silk screen print in a show with some other Berlin artists at City Hall in Los Angeles, and two women lawyers tried to get the work out of the show. They tried to sue the city for damages, because they said I had illustrated an anal sex scene. They protested that there were homosexual acts going on, which wasn’t true at all, because it was a heterosexual couple, but they interpreted it as an anal sex scene and wanted the city to remove it from City Hall. So the city brought in experts to evaluate the work. They said that this was highly recognized International art, and anyway it was a gift from the city of Berlin to the city of Los Angeles and that it could not be removed. These things happen all the time in different places. Sometimes before the show opens, I am told that this or that painting will not be included or that they can’t show it because of the public audience. The people who are bringing these shows together will have trouble with their bosses, or their Board of Directors. I feel that we are pre-judged now in the selection process.

MT: Well, don’t you think this shows that at least some of the public is not entirely indifferent. And it is usually the indifference that is so difficult to comprehend. Most often if an audience can’t be provoked they can also not be pleased. If one can get them to scream about their so called Christian morality, or try to drag the artist into court they do make people look for a moment and pay attention if but for the gossip.

S: Yes, but the only good artist is a dead artist