Robin Levy: A Space of Solidarity

Robin Levy, A Jew, A Book, and a Bench (in response to the January 6th insurrection at US Capitol), 2022, Jew, book, paper, sound [photo: Paul Hester; courtesy of the artist]

Share:

In 2021, I traveled to see Prospect 5: Yesterday We Said Tomorrow. As I prepared for the trip, a mutual friend connected me with New Orleans–based artist Robin Levy. During my visit, Robin invited me to her studio, and then we had dinner together. It was our first meeting, and I left feeling full, like when you’ve been reunited with a good friend. The work under discussion in this interview was in a nascent stage at the time. We walked past a bench on our way into the studio, and I heard the beginning of the story that would eventually become Levy’s installation A Jew, A Book, and a Bench (in response to January 6 United States Capitol attack). She first showed the work at The Silos at Sawyer Yards in Houston, and she has performed it once more since its debut. I imagine it will have an even longer public life. Like many artists whose installations undergo different contexts over their lives, she is steadfastly dedicated to investigating and learning from the work. This meeting sparked a series of conversations that have found their home here in this interview for ART PAPERS.

Joey Orr: The title of your new work is A Jew, A Book, and a Bench (in response to January 6 United States Capitol attack), right?

Robin Levy: Right. Hopefully, the title provides matter-of-fact language that informs the work. The January 6 Capitol Attack summoned me to channel my mother’s and father’s bravery and purpose. Unlike the 2017 Charlottesville protest, I watched the Capitol insurrection and felt an urgency to respond—and did you know about the recent National Day of Hate in February? I couldn’t stand by anymore, even if it meant doing something with only a few people around. On top of witnessing the horrific desecration of our Capitol, the symbols of white supremacy and Hitler’s Germany [on display that day] were beyond vile—because that spectacle was not just about hatred of Jews. I felt impelled to remind fellow Americans that Jim Crow race laws were the blueprint for [Nazi Germany’s] Nuremberg Laws. In the 1930s, Nazis came to the United States to learn all they could about [the United States’] codified white supremacy. They enrolled in law schools and met with prominent lawyers, senior political leaders, and pre-eminent eugenicists. Then they returned to Germany, replicated America’s constructs of race, anti-miscegenation laws, and eugenics—and obviously continued expanding their Aryan agenda. Getting rid of the Jews, [Roma people], homosexuals, communists—anyone who had an ideology or religious framework that didn’t align with Hitler’s. It was a very thin line. As a child, Mom was hiding under floorboards during the Holocaust, so it’s no surprise that she never thought she’d be in the public eye. Silence saved her life. But when David Duke became a public figure in her community, her fight-or-flight response took over. Until then, Mom was a quiet, fearful person who always remained silent about her past, like her parents required her to. Until she couldn’t. Until a circumstance—[one that felt] way bigger than [her own]—demanded that she confront the Holocaust denier. And she hasn’t stopped speaking up against racial prejudice, intolerance, and hatred since.

We’ll see if this work speaks to the general public the way it’s intended. I’m testing the waters tomorrow. Tomorrow is the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising’s annual Remembrance Day [officially named Holocaust and Heroism Remembrance Day]. Mom survived the Warsaw Ghetto with her family, so I’ll sit on the bench near the Holocaust Memorial in New Orleans. I’ve wanted to publicly activate the bench here for a while, and this seems like a quiet, respectful way to start. I’m always worried about staying in my lane when touching on complicated issues about humanity. Well, this is clearly my lane. As I watch my mother’s stamina decline … I want to preserve her story, partly as America’s story.

Robin Levy, A Jew, A Book, and a Bench (in response to the January 6th insurrection at US Capitol), 2022, Jew, book, paper, sound [photo: Paul Hester; courtesy of the artist]

JO: You’ve done this installation once before at The Silos at Sawyer Yards, in Houston, right? Could you set it up? What actually is happening in this installation?

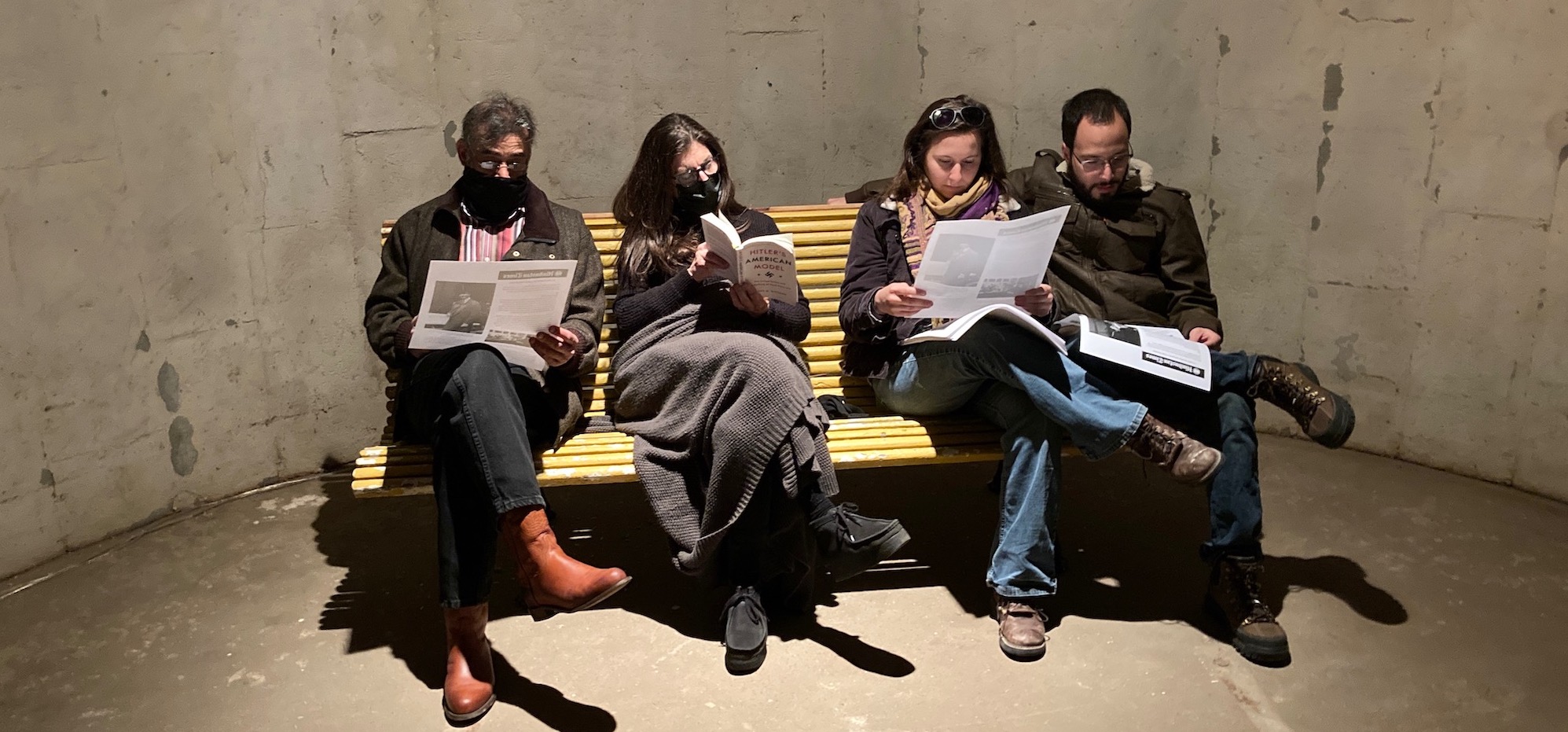

RL: Sure. I was invited to participate in an exhibition in which artists had their own silos. Bradley Sumrall, from the Ogden [Museum of Southern Art], one of two curators, thought the bench would really work in there. [We, the artists,] did whatever we wanted, but it was bare bones. We were given a space and electricity. It was perfect, because in December, January, and February [the space] was basically a dark, cold, damp bunker. The bench was placed inside the space, and because of the acoustics, I included the sound of goose-stepping, a formal military marching style. For me, witnessing the absence of a body was visceral. It never dawned on me to actually sit on that bench. Maybe because of the narrative I attached to it. But [artist] Sean Fader happened to be staying at my house when I returned home from the install. After [I finished] excitedly explaining activating the space, he immediately replied, “Robin? Aren’t you a Jew? If you really want to activate the space, you’ve got to sit on the bench.” I immediately felt queasy and said, “You’re absolutely right.”

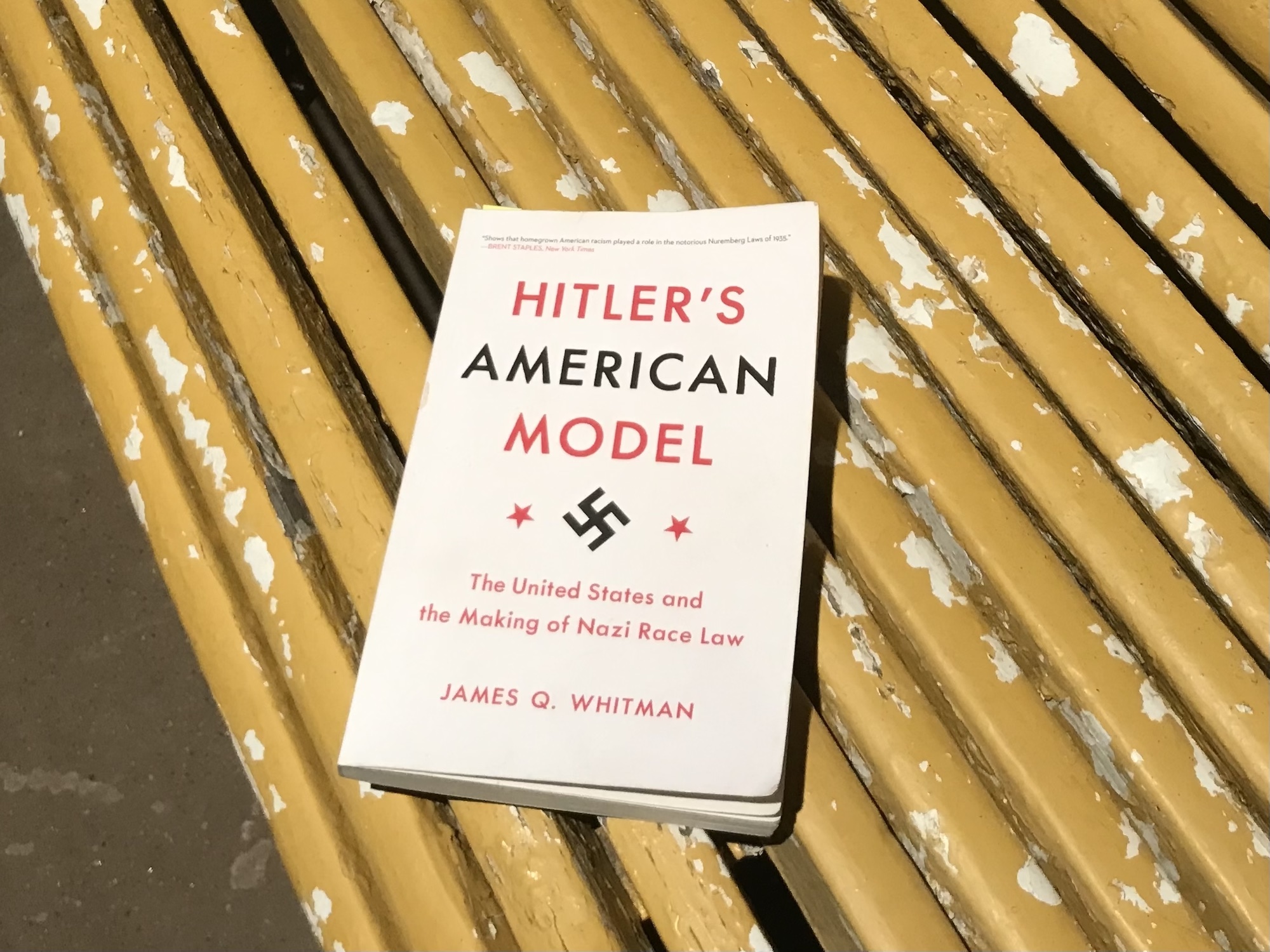

So, I’m reading a book quietly on the bench. Beside me, there’s a stack of handouts of oral histories from people who either witnessed a Nazi-era yellow bench, or sat on one, and the sound of goose-stepping fills the space. I’m intentionally showing James Q. Whitman’s book cover. The title, Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law —and the swastika—clearly state the book’s contents. The silo is small, and the only source of light hovers over the bench, centered between two doorways and nudged slightly towards the back. When someone enters the space we’re in close proximity, and I greet them. Most visitors choose to speak and then walk by. Others sit, and we spend time together on the bench. Some walk by totally uninterested, and I continue reading. If someone does say hi or stop, they usually take a picture of the book cover and pick up a sheet of oral histories. A Trump rally happened to be down the road during the Silos’ opening, adding extra drama to the experience. Most visitors expressed horror, then thanks for the introduction to the history, and for the resources to learn more. The United States’ consistent omission to teach this and so many other painful historical facts has failed to honestly educate its citizens and speaks directly to why our country’s imploding.

Robin Levy, A Jew, A Book, and a Bench (in response to the January 6th insurrection at US Capitol), 2023, Jew, book, paper, sound [photo: Robin Levy; courtesy of the artist]

JO: Could you say something about what the yellow bench is? And also, how you came to have this yellow bench?

RL: Yes. It’s so random and amazing. After watching the insurrection, I decided to go into history and find something that could connect what’s going on in America, now, with what was going on leading up to Hitler. I thought I’d connect with an artwork or a particular artist working during the Weimar period. But that strategy was upended when I discovered that Nazi Germany placed yellow benches in public spaces for Jews to sit on. Even before knowing anything about James Q. Whitman’s book, my reaction was, Oh, my God, that’s like Jim Crow. It reminded me of segregation here.

Anyway, my family was in the antiques business for most of my life, so I was confident I could find a European bench from that era—and connect our history of Jim Crow laws with this Nazi bench law. So, I asked some friends who were going to an antique fair, in Texas, called Round Top, to look for a late–19th-century/early–20th-century European bench. Nothing about color was discussed, because no one in their right mind would ask for an antique yellow bench from Europe, right? Within 20 minutes of Round Top opening, photographs arrived on my phone. Among them was an antique yellow bench imported from France. Wild, right? And unlike the others, this one projected function, not elegance. This bench was also much larger and heavier than the others. And, amazingly, it matched a park bench in a magazine photo I found online with a prominent Jewish French man standing in front of it, years before he escaped Nazi persecution.

After buying this bench and shipping it to my studio, I sent paint chips to nationally accredited paint specialists. They explained that paint chemistry remains the same, whether painted in 1900 or 2023. Optical microscopy can’t provide specific dates, especially for 20th-century paints. Their results were inconclusive, but no one concluded that it wasn’t painted during the Nazi era. So, then, I contacted the Belgian dealer who found the bench, and she confirmed several facts pointing to its authenticity—especially the fact that the bench was found in Lille, France, a city occupied by the Nazis. So, it’s totally plausible that it’s a Nazi bench. Most Holocaust scholars know nothing about the Nazi yellow bench law.

JO: Can you say a little something about the oral histories, where they came from, and how those were gathered?

RL: After learning about the yellow bench, I dug into the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum archives, and other online sources. Oral histories eventually surfaced. One was from a European woman who recalled going on a road trip with her father …. Let’s see. It says, “In the summer of 1938, my father took me on a wonderful European trip. We traveled through Berlin, to Switzerland, Belgium, and France. It’s very vivid in my memory, how we walked along Berlin’s famous street… and saw the yellow benches, which were different from all others, meant only for the Jews. As foreigners, we could have sat on any bench, but my father insisted that we should sit on a yellow bench, out of solidarity with the German Jews, and to get the feeling of what it meant to be excluded.”

Here’s another inspiring recollection from one of India’s best-loved columnists and writers, Khushwant Singh: “My first encounter with the Nazis came in 1935 when I was a member of the Indian Students Hockey team to play against German teams in Wiesbaden. There were benches kept in the field for spectators of which one was painted yellow. At half time, I went and sat on it. I was asked to sit on another bench as the yellow ones were meant for Jews. I refused to do so and got into an unpleasant argument with our German escorts. I was dropped from the team.” These personal stories breathe life into the narrative I’ve attached to this object. Life’s humanity and inhumanity span Germany’s horrific political past to warning signs of U.S. regressive legislation today.

JO: I was looking at an image of the poster that had some of the oral histories on it, and I was thinking about the space of the bench and who sits on the bench and why. When I read your title, A Jew, A Book, and A Bench, I thought about that space for a Jew as a space that can be occupied by many. You’ve talked about yourself. You’ve talked about your mother, and you mentioned [Roma people] and homosexuals. Before our interview, I was thinking about that famous Martin Niemoller quote, “First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out because I was not a socialist ….” and to summarize, they came for all the others, and when they came for me, there was no one left to speak. And, of course, Fannie Lou Hamer’s quote, “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.” The space of the bench is a space of oppression that has also been used as a space for advocacy and solidarity. How do you see your work opening that public space?

RL: That’s a beautiful tribute to those witnesses, thanks. Benches were originally designed for gathering and bringing people together. At various times in history, [and] even still, benches are weaponized to isolate or simply remove certain people altogether. I want to bring this bench back into community, sit with people of all kinds and, together, push back against hatred. Moments before the Silos exhibition opened, I sat alone on the bench with my eyes closed. A rush of emotion filled my body, [to my] total surprise. I guess the traumatic history I was channeling finally hit me when it came time to actually activate the space. But feeling overwhelmed finally transitioned into empowerment.

Robin Levy, A Jew, A Book, and a Bench (in response to the January 6th insurrection at US Capitol), 2022, Jew, book, paper, sound [photo: Paul Hester; courtesy of the artist]

Robin Levy, A Jew, A Book, and a Bench (in response to the January 6th insurrection at US Capitol), 2023, Jew, book, paper, sound [photo: Robin Levy; courtesy of the artist]

JO: We haven’t really talked about the book, yet. Could you tell me a little bit about how you found the book and its place in this project?

RL: I read a review in The Atlantic about Whitman’s book and immediately bought it. This book is the glue of this activation. Whitman wrote an exhaustive history to exemplify how fragile democracy is, especially now. Our American Experiment is at risk like never before. He gives myriad examples of the close relationship between Nazis, America’s Jim Crow proponents, and the Nuremberg Laws. He [highlights] ways our nation exported racism. But accessibility to his and others’ exhaustive scholarship comes so late …. Honestly, had these buried facts always been taught to middle schoolers, life would be so different now. White Supremacy is openly terrorizing the US today, and too many political leaders describe it as patriotism, not calling it out as hardcore racist nationalism. I’m reminded that my immigrant grandparents arrived belonging to an “inferior race,” but their children benefited from the life-changing trajectory of being classified as White. [Members of] America’s growing multi-race majority know their untold histories. Descendants of those who suffered chattel slavery, tribal annihilation, and marginalization steadfastly demand their inalienable rights, fair laws, and overdue reparation. Like-minded Whites must step up. Looking back on it, [my] growing up Jewish in the aftermath of Jim Crow, in an extremely Catholic city with deep African and Caribbean roots … taking public service buses to integrated public schools, these are just a few examples of how I began gaining awareness of the diverse worlds in New Orleans and learned enduring life lessons about my White privilege. I’m continually learning. Mostly from preeminent local Black artists, activists, and historians committed to identifying and correcting systemic inequities.

Robin Levy, A Jew, A Book, and a Bench (in response to the January 6th insurrection at US Capitol), installation detail, 2022, Jew, book, paper, sound [photo: Robin Levy; courtesy of the artist]

JO: You know, Robin, coming into this interview, I was thinking about just the actual act of reading, performing reading. I’m especially thinking about all of the book banning, and all of the legislation that people are trying to pass to keep certain kinds of [knowledge] out of the public education system. Sitting on the bench, reading, might seem like kind of a banal thing at first, but we’re living in a time when that act alone has such radical potential. It just really strikes me right now.

RL: I couldn’t express it any better. In essence, this work speaks to a power struggle over truth telling. These wild political times and our resiliency playing out at all levels of government will determine who we become. The worn-out quote comes to mind: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” But let’s remain hopeful that one day our nation and its lawmakers will audaciously celebrate our vastly different cultures … that have always existed. One day. But you didn’t tell me what you thought about the title.

Robin Levy, Facing Inward, 2018, archival print, 44.5 x 30 inches[photo: Robin Levy; courtesy of the artist]

Robin Levy, Hiding in Plain Sight, 2021, archival print, size variable [photo: Robin Levy; courtesy of the artist]

JO: Well, I was thinking about the title as a way to structure our conversation, actually. The title, in some ways, is almost like an itemized list. It’s almost the same as the materials that you list for the work. It pulls everything together. It’s about the space of your personhood and your own personal history, but our histories are never just our own. It seems to me this work addresses a broader effort that was shared across nation states, in very different contexts. Then, the last parenthetical part of the title, “in response to the January 6 United States Capitol attack,”—you’re just basically saying, and also today.

RL: Right.

Robin Levy, Up to My Ears, 2021, archival print, size variable [photo: Robin Levy; courtesy of the artist]

JO: I think it does a lot of good work.

RL: That’s reassuring. You have to find joy in some of this gnarly stuff. With this project, sitting together with others, having meaningful conversations with perfect strangers does it for me. I don’t have the words that really express just how disturbing these times are. But, you know, humor is also essential.

JO: Well, I[that] keeps it human. I think one of the most interesting things about that title is that it’s a description of the action. The Holocaust, or the Shoah, serves as the penultimate evil and injustice for so many people, and so it sometimes shuts dialogue down instead of opening it up. To think that there is a Jew from New Orleans sitting on a bench that was meant for Jewish segregation in Nazi-era Europe, reading a book that says the blueprint for all of that came from United States history—it’s really an invitation for people to sit down beside you on a bench and read history together. A time for honesty, as you say.

RL: I hope so. Epigenetics definitely informs this work, but the idea for this bench project, to perform an age-old activity with a radical overtone, came about because I’m an artist. I can’t totally understand ancestral traumas other populations of Americans inherit, but I can certainly relate. Getting ready to perform the work for the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising’s annual Remembrance Day in New Orleans, it didn’t make sense to ask the city for a permit. This action was about being subjected to the unexpected.

JO: It makes a lot of sense to me to stitch this piece into the fabric of public life.

RL: Thanks, Joey, I hope so. I’m not interested in being where I don’t belong. But I am interested in taking risks. How are boundaries best crossed in a way that builds community, that provides opportunities for deep meaningful connection? I inherited my mother’s fear, so I have to do some things that are courageous in my own mind. Maybe not in other people’s minds, but they’re courageous for me. And I don’t want to be tone deaf. We all make mistakes. I want to learn from mine, take responsibility for them, and for their impact on others.

JO: Sure. And these schemes can travel across different identity formations, so coalition building seems like an absolutely great place to go at the moment.

RL: I pray that most of the strangers walking by agree with you. Hopefully, it’s an opportunity to be with each other and to learn about each other … to share the countless histories we all bring into this world. It’s a bench. I hope it offers a way to be together.

Joey Orr is the Mellon Curator for Research at the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas, where he directs the Arts Research Integration and is affiliate faculty in Museum Studies and Visual Art. He previously served as the Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, where his major project aligned three exhibitions around artistic research. Recent writing has been published in ART PAPERS, Art Journal Open, BOMB, Hyperallergic, Journal for Artistic Research (Network Reflections), and Sculpture. Juried writing has been published by Antennae: Journal of Nature and Visual Culture, Art & the Public Sphere, Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry, Images: Journal of Jewish Art and Visual Culture, Journal of American Studies, PARSE, QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, Visual Methodologies, and a chapter in the volume Rhetoric, Social Value, and the Arts (2017). His first book, A Sourcebook of Performance Labor, was published by Routledge in 2023. He holds an MA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a PhD from Emory University. An Atlanta native, Orr is a founding member of the idea collective John Q.