Resisting the Spectacle

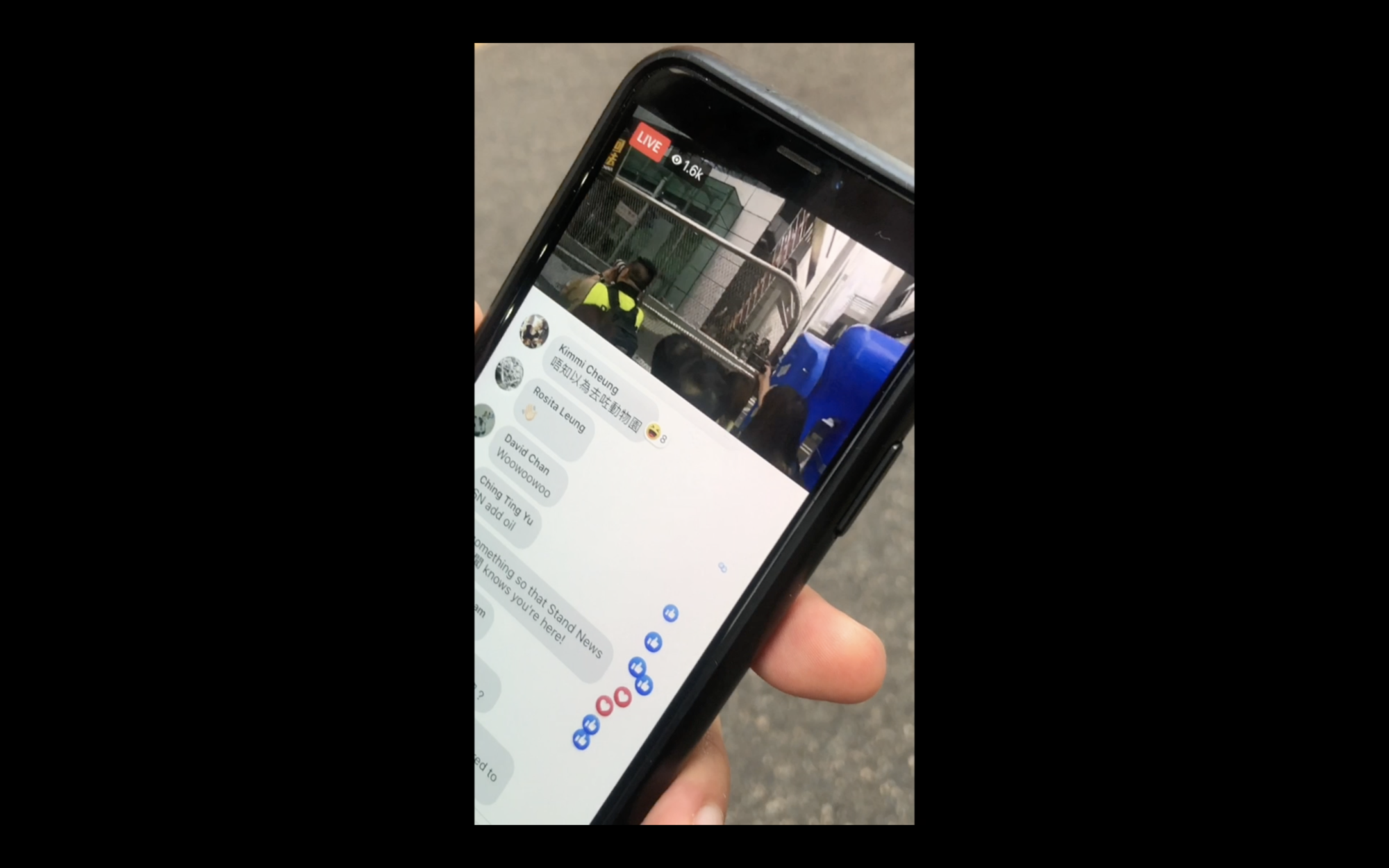

Tiffany Sia, Never Rest/Unrest (still), 2020, 29 minutes [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

On a typically dreary British Sunday evening in mid-September, my parents, my brother, and I sat around our dining table to discuss whether my 媽媽 (maamaa, mother) should return to Hong Kong to continue teaching at a publicly funded liberal arts university. Persons belonging to Hong Kong’s global diaspora, my family included, have always known that the Chinese government would never adhere to the 2047 expiration date it had given the semi-autonomous city. We could not have foreseen the forced rotting of Hong Kong, expedited by the 2019 extradition bill and the 2020 national security law, both of which emerged as systematized strategies by Beijing to quell recent political dissent. Staring blankly past my brother and me, 媽媽recalled the things she would miss most if she decided to decline the university’s invitation to rejoin the faculty for the following semester: the brisk communal sprint of bodies making their way to the MTR (Hong Kong’s major public transport system) during weekday rush hours, as if participating in a covert marathon; the cha chaan teng, steps from her apartment, which served her favorite late-night snack—thousand-year-old egg congee with a side of 炸兩 (zhaliang)1; and the restless convulsion of a populace that has been fighting for political sovereignty since its handover from British colonial rule to China in 1997. Despite a pronounced desire to resume her life in Hong Kong, 媽媽ended our dinner by affirming her decision not to return: “Hong Kong is dying, there is nothing for us there anymore.”

Tiffany Sia, Never Rest/Unrest (still), 2020, 29 minutes [courtesy of the artist]

Tiffany Sia, Never Rest/Unrest (still), 2020, 29 minutes [courtesy of the artist]

If Hong Kong is indeed moribund, the spectacle of this capitalist hub’s impending death drew the intrusive gaze of international onlookers. During the peak of the city’s well-documented political crisis, international media strongholds disseminated sensationalist images that could easily have been confused with stills from a multi-million-dollar film. The New York Times favored depictions of heavily armed police forces firing cartridges of tear gas at crowds of protesters wearing makeshift respirators, precariously shielded by a swath of open umbrellas. The Atlantic featured activists clothed in all black, crouched behind wood panels, engulfed in a cloud of mist, and backlit by a cool blue glow emanating from the city’s prominent high-rises. In Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕—an anti-travelogue publication which forecasts Hong Kong as the first post-modern city to die—independent film producer, writer, and artist Tiffany Sia observes that crisis news, and the images that accompany it, have become a best-selling genre of cultural production.2 But with the arrival and spread of COVID-19, Hong Kong’s globally reported and spectacularly captured political demise soon slumped far below the fold and into the archives of most media platforms. For centuries, anecdotes of civilizations struck by disaster and tales of abandoned cities have persisted in the popular imaginary, with collapsed or decaying locales—such places as Hashima Island, Japan; and Craco, Italy—becoming macabre destinations for travelers allured by a fascination with history’s many tragedies. What in Hong Kong’s endgame was unworthy of sustained attention?

I remember being inundated with apocalypse-related listicles in the early half of 2020, when COVID-19 was no longer viewed as an epidemic affecting people in lands far away: Best Apocalypse Movies on Netflix; Essential Apocalypse Fiction Novels for Quarantine; The 10 Items You Need to Survive an Apocalypse. These lists may have been a lighthearted distraction from our collapse into crisis, but as filmmakers Adam Khalil and Bayley Sweitzer remind us: “the end of the world is a matter of perspective. Most people think the end of the world is going to come for everyone at the same time. For [many], the end of the world happened a long time ago.”3 Indeed, apocalypse materializes in the state-sanctioned killing of Black men, women, and children; in the genocide of Indigenous people; in global pandemics, nuclear bombings, colonization, migrant detention centers, and the progressing violence of climate change. As noted by Sia, “It is not that the apocalypse only happens to some populations—but rather, that some groups, and nations, afford to buy more time in our expiring world.”4

For people unable to participate in the free-market of life-extension, demise brings its sinister sibling—the eventual foreclosure of shared memories. Names are forgotten, lineages disrupted, and histories are deemed unworthy of official archives. Throughout the political crisis, testimonies obtained from voyeuristic bystanders have found their way into the international discourse—a November 2020 article in The New York Review of Books branded the protests “fun, raucous, and creative” 5—but when it comes to the supposed death of Hong Kong, we demand witnesses who have lived in and through the city’s volatile political ecosystem. 6As the world peered in on a convulsing city—temporarily lured by images of police officers wielding batons against the curled, defenseless bodies of protesters—what was often neglected was the banal, joyous, and unremarkable time of political unrest. This omittance is redressed by Sia in Never Rest/Unrest (2020), an experimental short film recently premiered at the 16th Berwick Film and Media Arts Festival, and a companion piece to Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕. Opening with a shot of the sluggish ebb and flow of Hong Kong’s harbor as it reflects the black tar of night, Sia’s film, recorded via hand-held device, resists the fetishistic tendencies of news narratives and instead documents the intimacies of resilient political action and presents itself as a faithful witness to Hong Kong’s tumult.

Tiffany Sia, Never Rest/Unrest (still), 2020, 29 minutes [courtesy of the artist]

Throughout the film’s 29 minutes we observe Sia’s commutes from day to day, protest to protest. Clips of uneventful subway and ferry rides are cut with the shuffling feet of protesters as they haltingly meander the streets of Hong Kong while chanting 香港人加油! (Heung Gong Yan, Ga Yau! Go Hong Kongers!). This mantra persists throughout the film, expressed in unison amid an assembly of people jammed against the railings of Causeway Bay’s Times Square shopping mall who are directed by someone in an adult-sized Doraemon costume. Or as an intimate call and response between an unidentifiable woman in her high-rise apartment and a lone man standing in one of Hong Kong’s many narrow side streets.

Tiffany Sia, Never Rest/Unrest (still), 2020, 29 minutes [courtesy of the artist]

Tiffany Sia, Never Rest/Unrest (still), 2020, 29 minutes [courtesy of the artist]

Viewers witness the weaponization of infrared laser pointers as tools to distract the eager trigger of a brutal police force—a tactic that briefly re-emerged in the United States during the George Floyd protests—and as a strategy to obstruct the facial recognition capabilities of state-controlled cameras and drones. In one of the film’s longest clips, the camera accompanies anonymous protesters gathered on Hong Kong’s Lion Rock as they aim their flashlights at the vast expanse of the city’s arresting skyline. A glow emanates from the clustered architecture below, refracting through the clouds of pollution that linger at the city’s upper limits. A stream of popular pro-democracy slogans can be heard: 光復香港-時代革命, gwong fuhk heung gong-sih doih gaak mihng (Liberate Hong Kong—Revolution of Our Time), a slogan that now prompts legal prosecution under the national security law. Among them is a less subtle but equally effective declaration that the Chinese government should go to hell!, and shared laughter and cheers are also audible. This exaltation of fierce pride and joy seems to have been omitted from official documenting of Hong Kong’s deterioration. In a brief clip, shot from a birds-eye view, Sia captures seven middle schoolers performing the melody of 願榮光歸香港 (Yun Wing Gwong Gwai Heung Gong, “Glory to Hong Kong”), a composition that many consider to be the official anthem of the protests. Surrounded by hundreds of children, with backpacks strapped to the shoulders of most, these seven middle schoolers lead a sometimes off-key but overall touching and boisterous rendition of the song that has electrified the city’s desire for autonomy. Although exclamations from persons within the united effort against Beijing’s oppressive rule are profuse, other moments of the film simply document people playing Crowd City on their phones, tapping furiously at iPhones’ glass screens to amass an army of simulated followers, or navigating collaboratively built online maps by reactively swiping a finger up, down, or side to side to anticipate their next call to action. For some living in Hong Kong, life goes on. A dozen people practice tai chi at a park square—a common occurrence during the early mornings and one of the city’s weekend rituals—and the escalators leading busy bodies from the subways to the streets still creep on continuous loop.

Tiffany Sia, Never Rest/Unrest (still), 2020, 29 minutes [courtesy of the artist]

Sia bookends the phone-recorded film with a clip that is ingrained in the collective history of all Hong Kong inhabitants. It is the 30th day of June 1997—the evening of the Hong Kong handover ceremony. I hold few memories of this night, except for the fact that my vision was impaired by a downpour of rain, and the faces of crucial political figures had seemed muddy, like the portraiture of a novice watercolor painter. Hong Kong citizens had huddled under their umbrellas to watch the end of Britain’s colonial rule over the city. This event was supposed to be spectacular—an evening to mark the end of one era and the initiation of the next, commemorated with the theatrics of Chinese and British uniformed militaries’ restricted and rhythmic marching; and attended by the United Kingdom’s Prince Charles; Prime Minister Tony Blair; and China’s president, Jiang Zemin. What was particularly striking to me that evening was how completely tedious the handover ceremony was, and how much time we had spent standing in the rain, waiting for something grand to happen, waiting for perceptible change. What I realized that night, and what Sia’s Never Rest/Unrest captures, is that the images and videos which make their way to our timelines or TV screens are always representative of the most sensational moments of an event, and are designed to inspire a movement or incite forceful feelings of hostility, but anyone who has taken part in protest knows that these moments, in reality, are fleeting. They are sparks that propel us forward between the dull stretch of time uniting arrival and action. Although grand displays of discontent, anxiety, and unrest proliferate on mainstream media, for city natives such as me, the slow death of Hong Kong as a Special Administrative Region (“One Country, Two Systems”) manifested as a spectral figure, haunting the mundane activities of everyday life. Restaurants that once reverberated with unreserved expressions of political opposition now hum with muffled whispers confessing shared fears of persecution. Newsstands, which once flecked the sidewalks’ topography with a diversity of publications, continue to disappear, and storefronts crowded with pro-democracy slogans scribbled on Post-it Notes have reverted to safe harbors of excessive consumption. To witness the sociopolitical deterioration of this city has been to acknowledge that collapse at this scale will occur not as a swift undertaking but as a gradual putrefaction, accelerated and exhausted by an onslaught of aggressive lawfare. By bearing witness to the memories and experiences of Hong Kong’s inhabitants, Sia upends flattening depictions of a city’s dissent and transforms intimate, mundane moments into a means of agency through a counter-spectacle spoken by those who live it.

***

This feature originally appeared in ART PAPERS Spring 2021 // Mimicry, Camouflage, Transformation.

Sasha Cordingley is a writer and illustrator from Hong Kong and the Philippines. She received her BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design and her MFA from Goldsmiths, University of London.

References

| ↑1 | A Cantonese dim sum dish made by enveloping deep-fried breadsticks in a layer of silky, almost translucent rice noodle sheets, generously doused in a blanket of soy sauce and speckled with sesame seeds. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Tiffany Sia, “Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕: The Leak as Discharge,” 17th Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival, online. |

| ↑3, ↑4 | Ibid |

| ↑5 | Barbara Demick, “China’s Clampdown on Hong Kong,” The New York Review of Books, September 19, 2020, online. |

| ↑6 | Tiffany Sia, “Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕: The Leak as Discharge,” 16th Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival, online. |