(R)education: Exhibiting the Asian American Experience

O, installation shot [courtesy of FiveMyles]

Share:

On March 16, 2021, six women of Asian descent, among eight victims overall, were killed during multiple shootings in Atlanta and adjacent Cherokee county. The confessed perpetrator is a 21-year-old self-proclaimed incel White male. The Cherokee County Sheriff and the communications director handling the case initially made no mention of a racial motive or the possibility that the shooting could be a hate crime. The killings, and this failure to see any link between misogyny and racism, sparked nationwide outrage from activists, writers, and advocates against anti-Asian hatred. Many Asian Americans were reminded of their own trauma, and of the ongoing history of prejudice and discrimination that they face in the United States.

On view in New York during this incredibly difficult time were two exhibitions in which artists and curators presented work that subtly engages identity, history, and the trauma of being Asian Americans in the US: O, at FiveMyles in Brooklyn; and Heirlooms, at Loong Mah Gallery in Chinatown. Curator Marine Cornuet presented Tammy Nguyen and Thad Higa in O, whereas Olivia Shao gathered heirlooms from numerous Asian American artists and arts workers for Heirlooms. As an Asian American curator, I analyze these shows to take note of the artists’ and curators’ approaches to grappling—as individuals, and for the community—with atrocities through their work.

Thad Higa, Portable Library #8, seven tiny zines and one scroll, collapses to form a 3 x 3 x 15 inch cardboard box [courtesy of Marine Cornuet and FiveMyles, New York]

Thad Higa, Portable Library #10, tiny zines and a paper sculpture, collapses to form a 3 x 6 x 7 inch cardboard box [courtesy of Marine Cornuet and FiveMyles, New York]

These exhibitions seemed presciently organized to remind visitors of Asian American lives and stories in light of the Atlanta shooting, which, of course, was not the case. The shows are a part of a much longer history of Asian American artists and curators attempting to assert their presence and foreground the nuances of our stories. The hope is for the work to spark conversations that would change perceptions of Asian Americans for the better, as well as to hold white supremacist ideals to account. That this work must be ongoing saddens me, but it is not surprising.

Inspired by the Black Power Movement, Asian Americans organized in 1968 to leverage their collective power. The term Asian American was coined by UCLA professor Yuji Ichioka, who formed the Asian American Political Alliance and the term while he was a student at UC Berkeley in 1968. Before this term’s introduction, each Asian ethnic group was typically identified by its respective ancestry or by the pejorative “oriental”. From the 1960s to the 1980s, Asian Americans fought for their rights in solidarity with other activists of color. In 1970, the Basement Workshop was the first Asian American political group to form in New York City. Since the Basement Workshop’s founding, many like-minded groups consisting of artists and thinkers followed across the country, including the Kearny Street Workshop (1972), Asian American Arts Centre (1974), Asian American Arts Alliance (1983), and Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network (1990), just to name a few. Asianish (2018), which Nguyen is a part of, is just one of the most recent additions to the Asian American artist affinity groups. These gatherings, both formal and informal, create the much-needed spaces to process trauma and build community. Through these groups, artists and curators involved can perform vital educational activism through protests, public programming, and exhibitions.

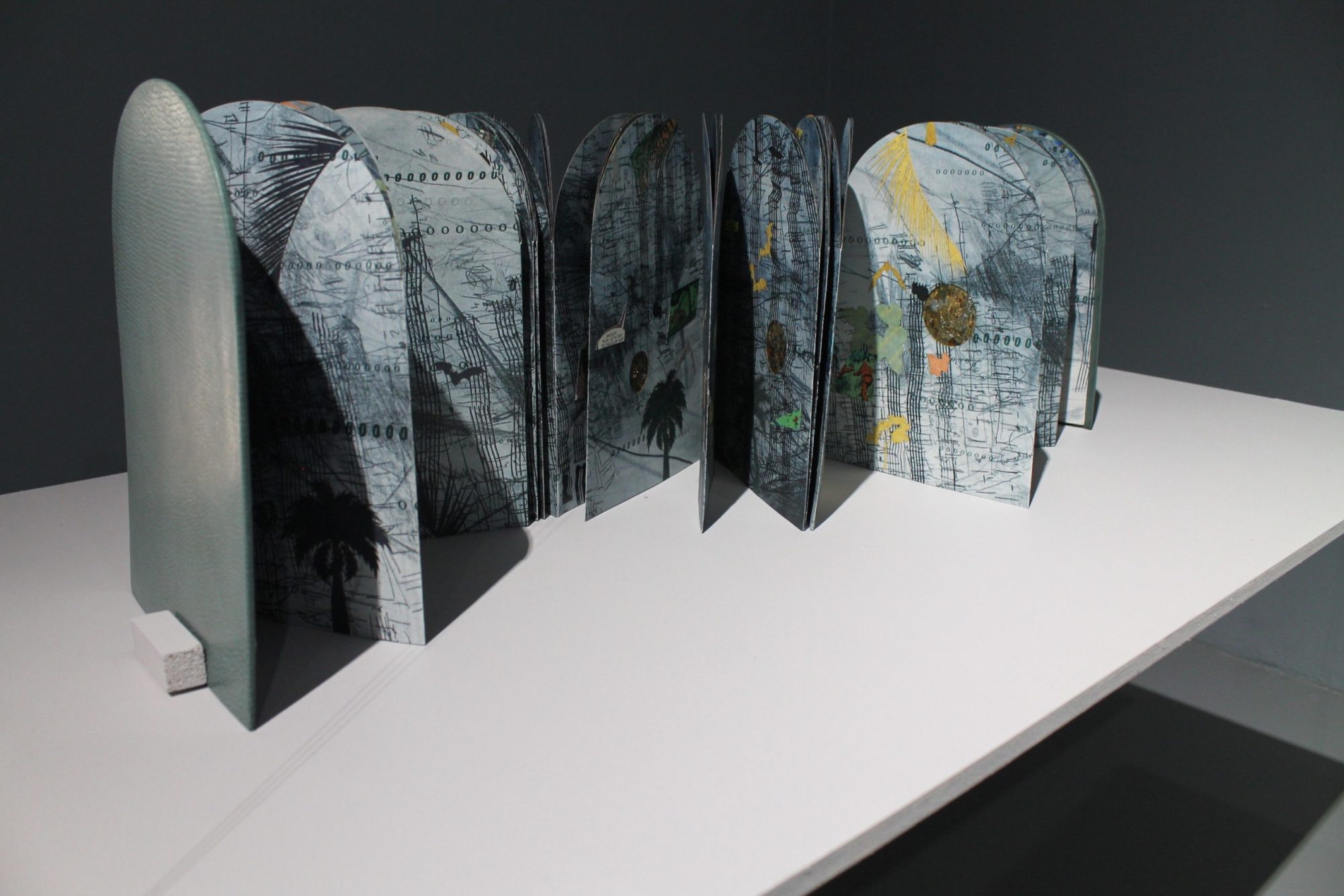

Tammy Nguyen, Four Ways Through A Cave #1, #2, #3, and #4, 2021, all leather, bookboard, letterpress, digital print and collage on paper, on floating tables [courtesy of Marine Cornuet and FiveMyles, New York]

I believe that Asian Americans find safety and support with each other in affinity groups, through shared experiences of racism and sexism. The fellowship formed is key to coping with ongoing trauma, and, in a wider sense, true for many people of color who are also working in activist contexts. I see Asian American communities coping with injustice through the following approaches: self-care and processing of events, which are inward and directed toward the self, to restore and recover; supporting the community’s efforts to process socially, which is still inward-facing; educating and defending the community through activism, which is outward facing toward people who are unaware, or who disagree but would listen to outreach; and finally, dreaming of new possibilities, which is also outward facing, to ponder and imagine what doesn’t yet exist. These four approaches can be used as a structure through which to understand the differing artistic and curatorial strategies in these exhibitions.

O foregrounds depictions of historical traumas against Asian Americans, and in doing so it demonstrates the inevitability of the Atlanta shooting. When considering O, I focused on the two artists’ use of those approaches to coping that are described above. Tammy Nguyen processes the Vietnam War through her art as a part of her self-care, and as a way for audiences to imagine new worlds. Thad Higa’s artist books work with hate speech as raw material to help him process language with racist biases. At the same time, he supports his own community by shedding light on verbal attacks, while educating a broader audience about language’s power to inflict harm and perpetuate it.

Tammy Nguyen, Four Ways Through A Cave #1 [courtesy of Marine Cornuet and FiveMyles, New York]

Tammy Nguyen, Four Ways Through A Cave #3 (detail) [courtesy of Marine Cornuet and Five Myles, New York]

Nguyen’s lacquered books and paintings, especially Four Ways Through a Cave (2021), encompass historical references to the Vietnam War. This war, which was only one of the more recent imperially incentivized moves by the US to exert control over parts of Asia, left the country in economic shambles and created a large refugee populace. Through Four Ways, Nguyen, whose family is from Vietnam, connected with the intergenerational trauma of being attacked and the ongoing hate Asians experience in the US. The work loosely illustrates the outlines of the Phong Nha caves in Vietnam and draws symbolism from Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. It also uses imagery from a Marvel comic, The ’Nam (1986–1993) which makes no mention of the US defeat in Vietnam. The narrative in the comic distorts history to preserve American exceptionalism. This disconnect from history evokes the characters in Plato’s allegory, who are unable to comprehend that their understanding of reality is untrue. Four Ways poses an alternative to that propagandist story by suggesting the Phong Nha caves that lead to the sun as Plato’s cave. In Plato’s metaphor, light stands for knowledge and truth that are going to make a new world possible. Nguyen symbolically passes through the Phong Nha caves herself, having processed the Vietnam War as a journey of self-care. Her readers (and she) glean new possibilities for the world as they move toward the light.

Alongside Nguyen’s work in O, Higa investigates internet-based alt-right hate rhetoric, and incorporates its exaggerated imagery and language into his work This Land is My Land (2021). By approaching the male fragility and White aggression present in these spaces as a disguise for deep-seeded insecurities, Higa finds common ground and understanding through an unlikely viewpoint. Beneath the hateful and territorial language against immigration and all foreign influences lies vulnerability that people with these feelings are unable to properly express, which then unfortunately manifests as violence, such as what took place in Atlanta. By re-presenting the strident alt-right writing, Higa finds a way to broadcast its hate to the Asian American community, and to reflect it outward to those who have yet to understand the dangers of being perceived as an immigrant in the US, even if one is wholly American. Understanding how Higa and Nguyen’s work constitutes the four coping strategies, the varied audiences of FiveMyles walk away with their own distinct lessons from the work, depending on their knowledge of the Asian American history.

Thad Higa, This Land Is My Land, unfolds in many ways and repurposes white supremacist speech and symbols [courtesy of Marine Cornuet and FiveMyles, New York]

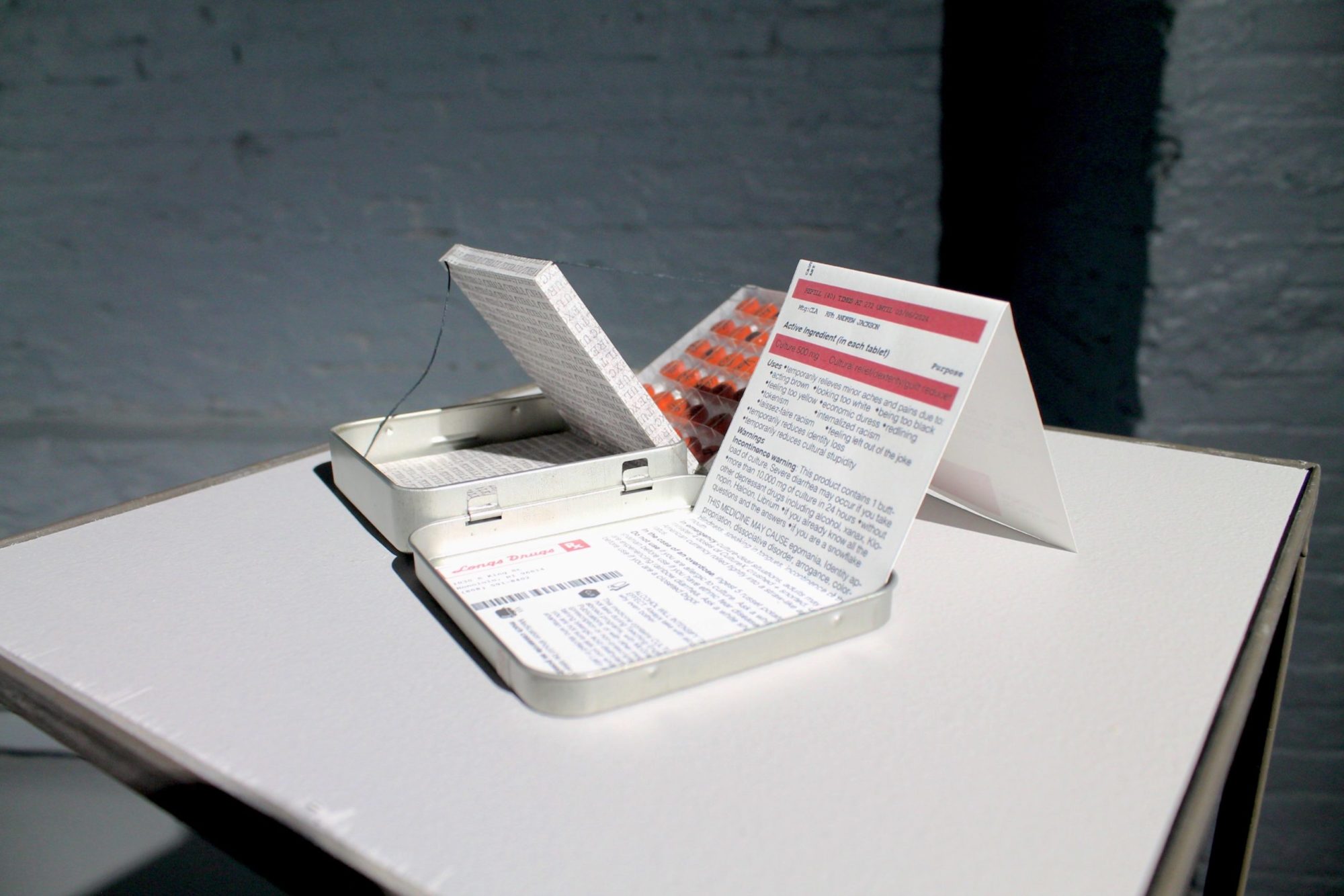

Thad Higa, Culture X, a sculpture in an aluminum box which includes hand-painted drugs and a prescription written by the artist [courtesy of Marine Cornuet and FiveMyles, New York]

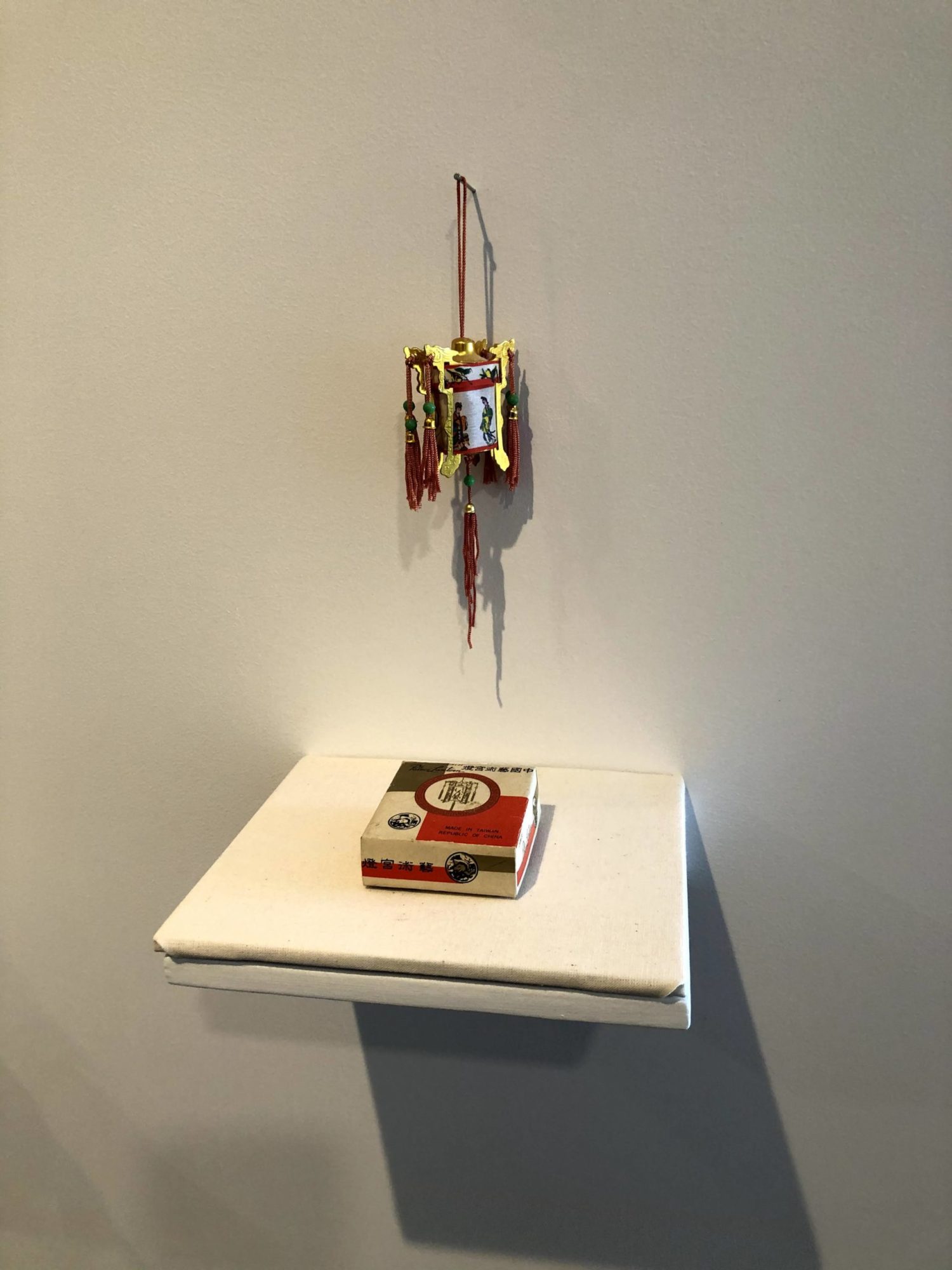

Heirlooms, in contrast with O, proposes a dialogical education through stories and objects to create alternative views of the Asian American experience. Heirlooms upends the likeliest viewer expectations created by its title. The heirlooms in the show do not necessarily possess extrinsic value; their value can be quite personal. Shao brought together an unlikely series of objects, including a dictionary, family photographs, an old radio, and a small paper lantern. The checklist of items, which visitors can carry with them through the space, serves as a guide consisting of narratives connected to each object, written by the artists and art workers Shao borrowed from.

Shao’s curatorial strategy enacts inward-community social processing by centering the stories of the Asian American community and educational outreach for the exhibition’s broader audiences. The dialogical gesture of storytelling enables viewers to learn personal histories that humanize Asian Americans and, for the community, allows us to feel seen. Personal narratives told through the collection of artifacts tackle unaddressed hate—the “Yellow Peril”—and desire—the “Yellow Fever”—that live within the substrates of the American psyche. Touching and personal stories suffuse the exhibition. I found myself tearing up, thinking, “We are just human, each with hopes and desires to live and thrive.”

Heirlooms, installation view at Loong Mah, 2021 [photo: Sophia Ma]

Heirlooms, installation view at Loong Mah, 2021 [photo: Sophia Ma]

To me, it is no coincidence that these two exhibitions and the horrific killings in Atlanta took place in the same timeframe. As Asian Americans, we are tasked to perpetually consider our identity within US borders; this persistent concern keeps us unsettled about our status as Americans in our homeland. Our hope of belonging is never quite realized. As Anne Anlin Cheng explains in The Melancholy of Race: Psychoanalysis, Assimilation and Hidden Grief as a racialized group, Asian Americans experience a “double loss.” We are rejected as Americans, our first loss; and also rejected as Asians in our countries of familial origin, our second loss. The result embeds an unshakable melancholy in our being, in our sense of self. We continue to be “othered” relative to White America. Artists such as Higa and Nguyen, and curators such as Shao and Cornuet expose the farce of this “otherness” in their work to highlight lived experiences of exclusion and the long historical presence of Asian Americans in the US.

Asian people, specifically Filipinos, have settled in what we know as Louisiana in 1763, but that date doesn’t consider those who arrived via the Beringia land bridge. A sharp increase in Asian people’s arrival followed the Immigration Act of 1965, however. At that time, many were selected for immigration thanks to their professional and technical knowledge. These highly trained individuals were often escaping the hardships of revolutions happening throughout Asia in the 20th century. They wanted to keep their heads down and not cause trouble, for fear that doing so might force them back to their old homes. So they swallowed the slurs and other bodily harm flung at them. Toiling as foreigners in a country that refused to recognize their humanity, many Asian Americans tried to numb themselves and forget this emotional pain.

Heirlooms, installation view at Loong Mah, 2021 [photo: Sophia Ma]

Heirlooms, installation view at Loong Mah, 2021 [photo: Sophia Ma]

In his recent documentary, We Need to Talk About Anti-Asian Hate, filmmaker Eugene Lee Yang closes the hour-long film by imploring everyone to talk, and talk, and then talk some more about these issues. Exhibitions such as O and Heirlooms can be taken up, along with Yang’s documentary, as contexts to start conversations. Let’s invite one another to look at the art of Asian Americans, and let’s have conversations that tackle racism and misogyny to avert future attacks like the horrible one in the state of Georgia.

Sophia Ma is an emerging curator. Most recently, she participated in SPRING/BREAK Art Show New York 2020, and she interned for the Arshile Gorky Foundation to work on the artist’s catalogue raisonné. For her graduate thesis at Hunter College, CUNY, she wrote about the work and spiritual practices of abstract painter Bernice Lee Bing. Ma worked in development, programming, operations, and administration for the Museum of Chinese in America. Currently, Ma is researching for a manuscript on landscape architecture, due for publication by Rizzoli New York in fall 2021.