Randy Ford: How To Pave a Street for Queens

Queen Street performance, 2019 [photo: Kat Young Designs; set design: Marcos Everstijn; lighting: Dominique Thomas; courtesy of Randy Ford]

Share:

Years ago, I met Randy Ford at an exhibition opening in Seattle. Let me rephrase that. Years ago, I was entranced by the energy radiating from Randy as I entered an opening reception. I was one of maybe six Black folks in the space, Randy being another, and I struggled to feel like I belonged as I navigated the white cube. Although the showing artist was a Black woman, the discomfort of Blackness being put on view predominantly for White eyes transformed into a dryness in my throat that could not be quenched by middle-shelf Cabernet Sauvignon. I approached Randy and thanked her for her entire presence. We began a talk that helped me realize the impact her work would have on a future wherein Blackness and queerness are centered.

In 2019 Ford first presented Queen Street, a dance showcase that she describes as a “physicalized experience through the lens of queer, trans, non-binary, and gender-nonconforming people of color.” Ford and I sat down to talk about Queen Street’s exploration of the physical, mental, and spiritual transitions of its performers.

Queen Street performance, 2019 [photo: Kat Young Designs; set design: Marcos Everstijn; lighting: Dominique Thomas; courtesy of Randy Ford]

Mia Harrison: Queen Street was really beautiful. There was an alchemy, or a transformation of trauma, happening on stage. I felt an energy shift from the beginning to the end. Could you tell me about how you felt after the performance was done? I saw you moving through it, and even the first scene, with the wrist. Was it “check your wrist?” or “straighten your wrist?”

Randy Ford: Fix your wrist. I couldn’t [safely] do this growing up—dangling my wrist in a very soft fashion. That scene, I call it The Rebirth. It transforms that trauma and throws it back. It’s all of the things about being policed as a young queer child who’s outwardly queer. I’ve always been noticeably different. Laverne Cox said this, too. She said [she] was never ridiculed for being perceived as gay, [but] for being seen as a feminine Black man. It wasn’t her sexuality, it was how she expressed herself. With that scene, I had to start at the beginning, start with her being born and him dying. When people came up to me, specifically family—other QTPOC community—saying, “Randy, I was so triggered in that whole bit.” People still talk to me about “fix your wrists.” They’re like, “Bitch, that was literally me growing up,” and I think that is something that I’m still sitting in because I want people to be seen in this show, because I didn’t see nonbinary, transfeminine people being uplifted, being praised.

MH: This is not the first time Queen Street has been a thing in its own entirety. Before it started more as a festival and a showcase. Could you tell me how we got to the [current] performance piece?

RF: The name Queen Street came from the King Street Station—the train station in Seattle. I got a solo for this festival called Out of Sight, which [is] a month of performance art happening in that gallery space. And I was like, fuck King Street, this is Queen Street and I just ran with it. It came from a solo that I did, and that particular solo [was about] me realizing that I was sexually assaulted, years after the assault. My femininity was used against me. So I made a dance piece about it, and then I said okay, people need to know exactly who I am.

I want this to be my Lemonade album. I want this to be my A Seat at the Table. My Black Bois. I always told myself, I want there to be a festival for nonbinary, Black, disabled sex workers. I want to put them in a festival during the daytime. Not a nighttime thing.

MH: We’re not hiding anyone.

RF: Right! We’re not hiding. Not just during pride month. How come we don’t have access to public spaces? As a teaching artist, I have access to students who are just—mind blown. Just being like, “You’re trans?” I was like, “Yeah,” and they were like, “Okay.” My students are the first ones to fight for me when someone misgenders me.

MH: When people talk about trauma, a lot of what they discuss is of the past and trying to move through the traumas that were inflicted in their childhood. But people [also] discuss shifting trauma through an intergenerational lens. So, you doing this work is not just healing you, now. It’s healing you, your 10-year-old self, your 15-year-old self, your 20-year-old self, your 60-year-old self—all these things at one time. How do you feel this type of work is allowing different generations to come in and heal?

RF: I wanted Queen Street to be the hub where all of these worlds can come together. I wanted this to be a space where an executive person can be in the same room as a sex worker, the same room as a child, the same room as an elder, the same room as a disabled person, the same room as a White person. Yes, my lens is … a queer, nonbinary, Black, trans feminine lens, but there is something for everyone to take away from this show. We are all continuously unlearning so many things. A lot of women are like, “I wish I could wear that,” and I’m like, why can’t you? Or a man saying, “I want to call you beautiful, but I can’t,” and I’m like, why can’t you? My favorite question growing up was “Why?”

Queen Street performance, 2019 [photo: Kat Young Designs; set design: Marcos Everstijn; lighting: Dominique Thomas; courtesy of Randy Ford]

MH: I thought it was interesting that everyone [in the performance] uses different methods to tell or educate. One of them was very much about calling out the ways that people perpetuate traumas. In one scene, Chip was looking to the audience and clapping after putting you into a very uncomfortable oppressive position—and people started clapping. How did you feel about that scene, and how do you feel about it when your audience is predominantly White, or even when they’re Black and they might not be part of the community? How do you get the audience to reflect on how they might be part of the problem?

RH: That scene, that part specifically, is always very telling. Sometimes there are no claps, which kind of makes me a little bit happy, sometimes. When they do clap it’s a way for me to let people tell on themselves. It’s a metaphor for all of the things we let slide and assume trans people have the skin and souls and spirit to withstand. That is not the case. We are actually very squishy and human like everyone else and very insecure and have all of these problems. I wanted people to educate themselves and be like, oh, shit, why did I clap? Is me clapping me being complacent?

MH: I felt like it was subverting the whole role of the audience and the performer and really making the audience question, hopefully, where their role is in this whole thing as the viewer, as the voyeur. I felt like a lot of the piece spoke to this voyeurism, and not just in the sense of “Oh, we’re watching Black, queer, trans performers on stage,” like, this is a fetishization and eroticization that happens on a day-to-day, too. How did you and the other performers deal with these conflicts? How were you able to support each other or create dialogue around the work that you’d be producing and performing?

RF: We talked a lot in rehearsals. I wanted my rehearsals to be nonhierarchical. Not like, “I’m the director, you’re my dancers.” I was like, “No, we are collaborators.” I treat every single person on this team as a collaborator. This was, yes, Randy Ford’s show, but it [also] was very much our show. And so we had a lot to talk about. Saira uses a cane. I was like, “Saira, if there’s ever anything that we’re doing [that feels risky or uncomfortable], please modify.

I don’t want us to look the same. I’m not here for us to look like a bunch of Randys on stage. I want us to look like ourselves. We asked where our joy was. A favorite question that Dani [Tirrell] always asked: where is your joy? So we ended all our rehearsals [by] reminding ourselves [to ask] where your joy is in all of this, because we’re going to be talking about some heavy stuff. A lot of people aren’t going to get half of the things that we’re doing. It was a last-minute decision to add in the rants—I call them rants, but where the performers had a chance to speak after or before their performances. That gave them agency to really talk about [topics like] ableism with Saira, the exceptionalism that we place on queer and trans performers with Keelan, the why with Chip.

Queen Street performance, 2019 [photo: Kat Young Designs; set design: Marcos Everstijn; lighting: Dominique Thomas; courtesy of Randy Ford]

MH: [You are] consciously making choices about who [in terms of the performers] is going to benefit the community and take the community to the next level. That means bringing in the collective knowledge that we all have and sharing it as a way to strengthen the Black community—realizing that the problem isn’t just on the outside; it’s also on the inside, and how can we have accountability to each other. I feel like I saw that a lot in the show, especially in one of the scenes where they were saying, “Oh, she’s not femme enough,” or, “She’s not this enough.” How do you feel your artwork in general confronts this narrative?

RF: I think not being interested in using White supremacist tools to uplift ourselves as a community has been the biggest thing. White supremacy gives you automatic results. Whereas [with] this work, you’re not going to see results the whole time or right away, even. Queen Street isn’t some mind-blowing, original idea. It’s just continuing the conversation. I just have always seen my work, myself, my art as [a way] to continue the conversation. I see Queen Street as a movement, a continuous step into that renaissance we’re always talking about.

MH: It’s an act of care.

RF: It’s an act of care. It’s energy exchange. I think Queen Street also has you thinking … what type of energy am I putting out into the world? Because—and this is going to get shady real quick—I get very irritated when people use those hot buzzwords like “community,” “equality,” “equity,” but are in it for themselves [laughs] and aren’t honest about that. I think it’s okay to be like, “I want to be rich and successful and never be broke again,” you know what I mean? By all means, get your coin, sis. But do not say you are for the community if you are not doing community work. That is my biggest issue. I’ve been an educator for six years, since I was 20 [and a] college dropout. I’ve been doing this. I’ve been living in this. I know my shit is dope.

MH: And do you feel like that’s an issue in Seattle? Because, as you’ve stated and as we both know [through] growing up in the Pacific Northwest, there’s not a lot of us here. And so a lot of people speak about community or seeking a community.

RF: Specifically for Black people. I feel like there’s a type of Blackness that Black people like to uplift and a type of Blackness that Black people do not uplift. We’re all doing our things, but we’re not really trusting each other. That is what I want to see. I want this Black network to interact with the international district network, who’s also going through displacement and stuff like that. How can we reach out to the Latinx community?

MH: Like a cross-pollination?

RF: A cross-pollination and just through that, togetherness.

MH: I feel like that’s always a tough one … solidarity. Because right now, your work has focused a lot on Blackness. Do you feel like your work will continue to center Blackness or trans, queer, nonbinary issues? Where do you see the trajectory of your work going?

RF: I think because I’m a Black person I will always be unpacking Blackness, inevitably. I think Queen Street will live on forever. I can’t wait to see it when I’m 40. I can’t wait to see it when I’m 60. I think I will always be interested in what’s happening in people’s heads versus what we see on the outside.

Queen Street performance, 2019 [photo: Kat Young Designs; set design: Marcos Everstijn; lighting: Dominique Thomas; courtesy of Randy Ford]

MH: So how do you recharge after doing this work and navigating life on a daily basis?

RF: I give myself—and it’s not nearly enough—a day. I take my time and tell myself the world will still spin, people will be fine, you can take your time. You don’t have to answer that. I’m giving myself permission to do that. I love a skincare routine, I love a bath, I love doing my hair. I love watching anime. I love eating and cooking. I love being naked, and just listening to music. I have been talking to someone and I love pouring into them. Pisces!

I think, moving forward, and going back to how I want to be received as an artist, I want to be received as someone who makes work but can also not be as accessible. Because I love opening up and being vulnerable. Don’t get me wrong, I think vulnerability is one of our strongest superpowers that we have yet to tap into. But there are definitely some things that I want to keep for myself. I think I want to be received as someone who gives what they give, and then no one questions when I’m not giving. Because it’s for me, and it’s mine.

MH: At the end of Queen Street you [ask] yourself what you would tell the 10-year-old version of you, but what would you like to tell the 40-year-old version of you?

RF: I would love to tell the 40-year-old version of me, “I can’t wait to get there.”

MH: Is there anything that you would like people to know or question or think about today?

RF: Yeah, actually, one of the biggest things I like to ask people, especially in an audience setting, is, if your only interactions with trans people or with nonbinary folks or with any marginalized community is through avenues to where they’re performing or they’re giving you something, you need to look into that. Because that’s very mediocre compared to the support these actual communities need.

Support is more than just showing up. Look into how you are perpetuating capitalism, White supremacy, look at how you are perpetuating ableism. And do that work yourself.

Mia Imani Harrison is a Pacific Northwest native, interdisciplinary artivist (art + activist), and arts writer. Harrison interrogates the ways that disenfranchised communities can heal individual, communal, and societal trauma by creating works that live in between the worlds of art and science. This “third-way” mixes unconventional methods (dreams, rituals) and science (ethnography, geography, psychoanalysis) to dream new potential ways of being.

Randy Ford is a Seattle native, dancer, choreographer, actor, activist, curator, and educator. She has been featured in CD Forum’s Showing Out: Contemporary Black Choreographers, Bumbershoot, Dani Tirrell’s Black Bois, BenDeLaCreme’s Beware the Terror of Gaylord Manor, and Kitten N’ Lou’s CAMPTACULAR! and Jingle All the Gay!. She created and co-produced her first full-length evening show, QUEEN STREET, at Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute with CD Forum in September 2019. She is a member of Seattle’s Au Collective, a dance organization committed to putting queer people, womxn, and people of color at the forefront of everything it does.

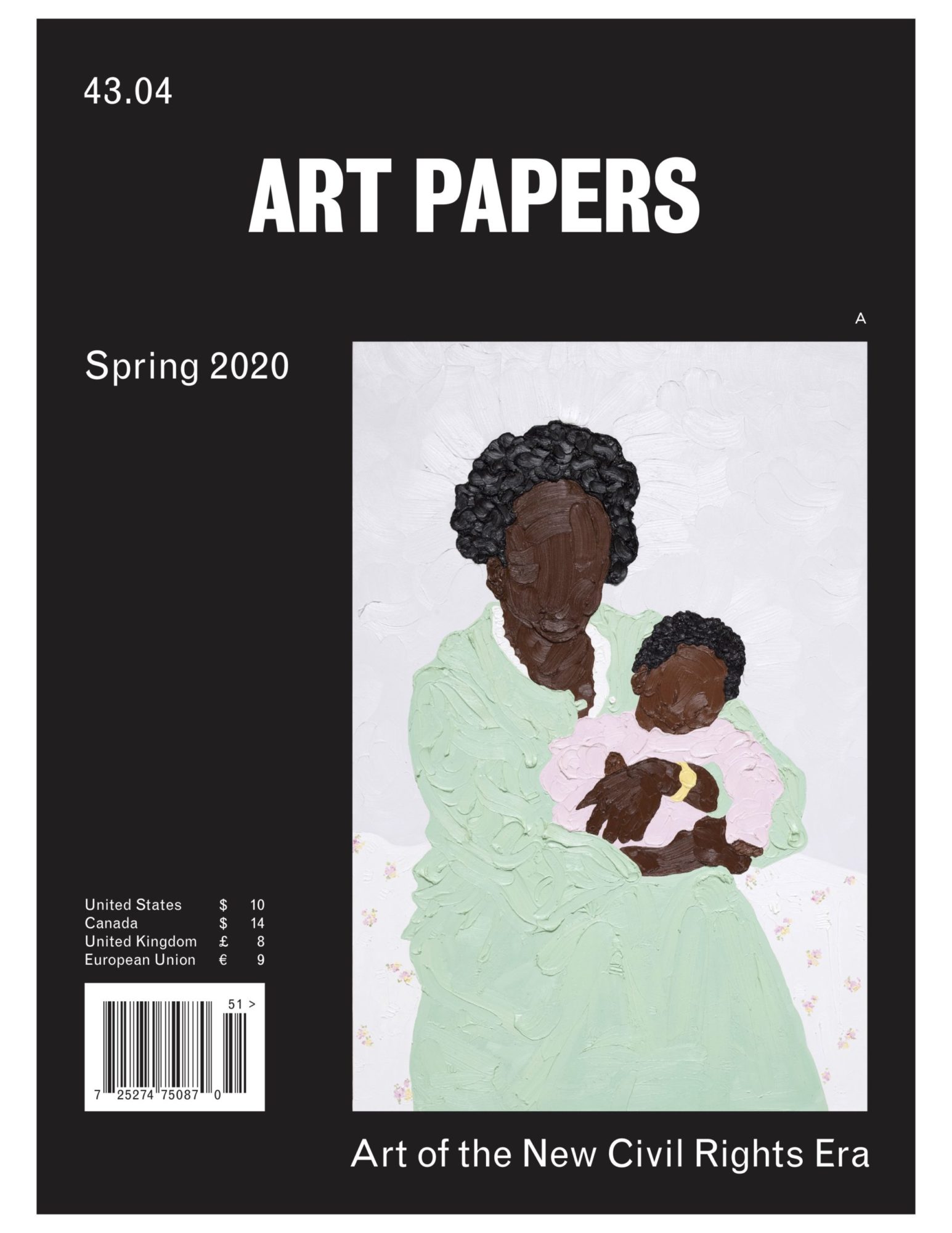

This interview originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Spring 2020 // Art of the New Civil Rights Era.