Prospect.6: The Future Is Present, The Harbinger Is Home

Hannah Chalew, Orphan Well Gamma Garden, installation view, 2024 [photo: Alex Marks; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

Share:

On the last morning of October 2024, small talk on the way to the opening of Prospect.6 lingered on how hot it had gotten. How we’ve run out of ways to describe how the sun feels differently on our skin, now. Our minds are responding to environmental collapse in strange ways. While the most stubborn still opt for the self-defense mechanism of denial—Business-as-usual! Disaster is “natural” and only happens people who live there!—those who face the harsh reality head-on are given this reward: the beautiful parts of life on earth become clearer in the face of their loss. The Japanese call this bittersweet clarity mono no aware, a concept powerfully captured in artist Ruth Owens’ Black Delight, An Ecopoem (2024). Owens’ video installation illustrates the heart of Prospect.6: The Future Is Present, The Harbinger Is Home. It was the first work in the triennial to deliver a gut-punch to my own eco-grief.

Black Delight, An Ecopoem is a love letter for the artist’s Louisiana home that unfolds in two scenes: a waterborne view of the coastline—one that we know is disappearing—and a Black dance party that is tender, then joyful, then bursting energetically at the seams. The videos appear to document the same time of night in places that seem worlds away from each other, but also just down the street. They present evidence of interconnected life at the water’s edge, which is sustained with a localized evolution of ecological balance through culture: countering grief with celebration; unnatural silence with familiar music; and nostalgia with the creation of memories, now, while we can. The videos are projected in the round, covering all four walls of the room and surrounding viewers with eye-level Louisiana horizons, as their shadows cast on the walls. As I become a part of the installation, I try not to make an impact on the landscape, causing me to choose my vantage point with care as I tried to witness everything, all at once.

Ruth Owens, Black Delight, An Ecopoem, installation view, 2024 [photo: Jonathan Traviesa; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

Ruth Owens, Black Delight, An Ecopoem, installation view, 2024 [photo: Jonathan Traviesa; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

Prospect.6: The Future Is Present, The Harbinger Is Home is the sixth iteration of New Orleans’ celebrated art triennial. It features works, installed throughout the city, by 51 prominent contemporary artists. Prospect.6 is curated by Miranda Lash, a former curator at the New Orleans Museum of Art, and by internationally acclaimed artist Ebony G. Patterson. The concept of Prospect.6 positions New Orleans as a harbinger—a military term for a person who ventures ahead and announces what is to come. This premise extends beyond the city’s geographic vulnerability to climate change (a reality shared by many frontline communities worldwide) or its ongoing struggles with post-colonial histories (also, tragically, not unique) to highlight New Orleans’ profound cultural legacy as a hub of an interconnected global majority—a place where historical and environmental challenges are met with searing insight and boundless creativity.

The triennial asks questions about navigating a world in flux that now have relevancy for many people—including myself. Following Hurricane Ida, and after 14 years in New Orleans, my partner and I decided to move our family in search of a more climate-stable home. Our family of 4 was part of 32 million displacements caused by weather-related hazards in 2022, a 41% increase versus 2008 levels. We live in a time when there are more people on Earth who live outside their home country than ever before in human existence. Millions are asking themselves: Can we afford to leave? Can we afford to stay? How can we carry our home with us as we go, if not physically, then symbolically—just enough to teach our children the lessons we hoped they would’ve learned there? Prospect.6 is conceptually grounded in these dilemmas and born from the artists’ lived experiences of trying to resolve them. For some artists, these conversations were happening in real time, as they produced their work for the exhibition.

Perhaps in answer to activist Grace Lee Boggs’ question “What time is it on the clock of the world?” Lash and Patterson curated the three final performances of opening weekend to lead viewers through a narrative arc of collapse and renewal aligned with the position of the sun. This zoomed-out temporal perspective mirrored the conceptual framework of the triennial, suggesting history’s cyclical nature and lambasting the imperial systems that have destabilized our present and led to an uncertain future. It’s possible that each work in Prospect.6 can be situated within these dimensions of decline, afterlife, and rebirth to offer insights into how we might move through what happens next. Let’s begin with dusk.

Decline

Beginning precisely at civil dusk—the time of day when the sun dips below the horizon and the sky begins to darken—Bethany Collins conducted a moving performance of the same name at the Marigny Opera House, once a 19th-century church with a romantic patina earned from repeatedly withstanding hurricane forces. The cavernous interior was empty except for streams of fading twilight coming through stained glass windows and two voices singing repeated rounds of Auld Lang Syne. Viewers fell silent as they walked softly in and out of the reverent space. As darkness fell, and it became increasingly difficult to see with clarity, the original lyrics gradually shifted—from nostalgic farewells to a bygone world to verses written during the Civil War, and then to new lines infused with themes of justice and revolution—striking a chord, for me, on the eve of an election that had disregarded the wishes of a majority opposed to genocide.1 The two voices seemed to be searching for synchronization but found it only briefly.

Without electricity, the church evoked its role as a shelter for weathering storms, recalling the days after Hurricane Ida and foreshadowing what might lie ahead. I found myself replaying the last time I had stood in that space, before the pandemic, watching my three-year-old son walk down the aisle and scatter rose petals for a friend’s wedding. Those memories felt more fragile than ever as I contrasted them with the monochromatic darkness descending around me. Civil Dusk asked us to recognize the moment we exist in—a period of obscurity, ambiguity, and gradual decline, when we can continue our day-to-day activities until we can’t. Collins ended the performance when the sunlight no longer illuminated the west.

On the other side of town, just upriver from the Fly at the Batture, artist Chris Cozier constructed a section of parade-style bleachers adorned with decorative colonial feet, titled it has already been decided …. The bleachers face the Mississippi River at the tail end of an 85-mile petrochemical corridor known as Cancer Alley, a space dominated by looming industrial tanker ships. Cozier draws a sharp connection between oil and cultural extraction in his home, Trinidad and Tobago, and the ongoing colonization of the Caribbean and New Orleans, where people are often expected to perform their culture for spectators, echoing imperial social hierarchies and fueling capitalism. The two places also share the tradition of Carnival, a spectacle that both reveals and reenacts entrenched social hierarchies—at times exorcizing the past, at times reinforcing divisions—all while spectators watch from the bleachers, somewhere between witnessing history and enjoying distraction. On a larger scale, it has already been decided … asks us to question the position we find ourselves in, as we watch the inhumane effects of colonial history unfold across the globe and our screens. Are we powerless? Passive spectators? Or could attention become our fuel?

Christopher Cozier, it has already been decided…, 2024, steel, enamel, and Sapele wood [photo: Alex Marks; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

Christopher Cozier, it has already been decided…, 2024, steel, enamel, and Sapele wood [photo: Alex Marks; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

During an opening weekend panel at the Contemporary Art Center, artist Mel Chin offered one of the triennial’s most poignant reflections upon decline. He reflected upon his time in New Orleans after Katrina, on how Hurricane Helene had just destroyed his town in North Carolina a month earlier, and then he showed a drawing of a 2,000-pound bomb that the United States sent to be dropped on a 5-month-old boy named Muhammad. His voice trembling slightly, Chin turned to face the audience. He said:

What I’m going to say is that the harbinger is [about] how we conduct ourselves. The actions that we have to have to … resurrect our humanity. That’s the job description. And how it’s not about our individual capacities—or maybe our collective capacities as human beings—to act, which we have not done enough. It’s a frustration with myself as an artist that, after a lifetime, I would witness this. And I am responsible, because as a citizen of the United States, I support, fiscally, these horrors and this inhumane condition ….

Amid pin-drop silence, he continued, “We’re entrapped by the world that we have created. It’s a fierce obligation to be tougher than this …. How do we use our creativity to create a climate of compassion and action? … I will continue to conduct myself in a way that I will take any action, in any shape or form, that’s possible. Because I can’t bear the sadistic kind of horror that I’m part of.”

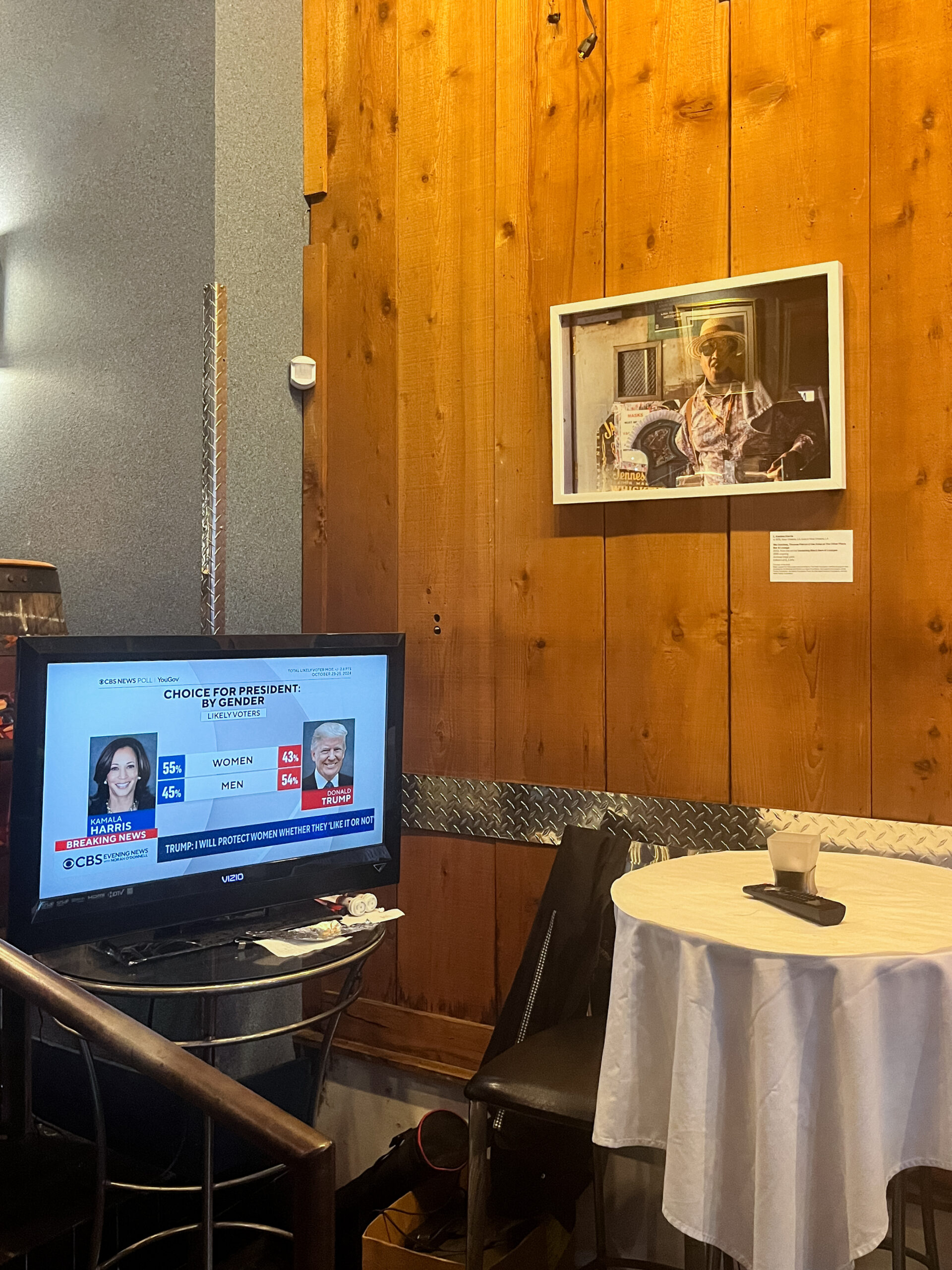

What we know may be ending. But of course, all life makes new life. Matter will change and will continue to exist, finding new forms. Some call this death, and in New Orleans, death is followed by a celebration of life. And so, Civil Dusk ended and people flocked to Sweet Lorraine’s Jazz Club for a party hosted by New Orleans photographer and former journalist L. Kasimu Harris. His work chronicles the disappearance of Black-owned bars across the city and the nation, highlighting their role as vital spaces for community and cultural preservation amid ongoing systemic erasure. For Prospect.6, his photographs were displayed at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art and Sweet Lorraine’s, grounding his work in the history of a club that has weathered the forces of erasure his photography exposes.

Sweet Lorraine’s has changed locations and names since its founding by the Sylvester family in the 1940s, as it adapted to redlining, segregation, the construction of I-10 through Tremé, Katrina, and other capital-fueled storms.2 Despite these efforts to dismantle this “garden of joy” (the club’s original name), it remains a cornerstone of New Orleans’ cultural landscape. Stewarded by Lorraine Sylvester’s grandson Paul Sylvester, Sweet Lorraine’s continues to host legendary jazz musicians and second line stops, proving the unyielding spirit of Black culture with every celebration.

A photograph by L. Kasimu Harris on display in Sweet Lorraine’s Jazz Club, alongside the bar’s news coverage, four days before the presidential election [photo: Heather Bird Harris]

The bar was packed wall to wall as Delfeayo Marsalis’ band warmed up and curator Miranda Lash took the stage to introduce Harris. Although the curatorial framing felt intentional and well-deserved, the vibe shrank when Lash described the importance of Black joy in a space where that significance was already deeply felt. When the phrase “post-Katrina” was spoken, a group of New Orleanians behind me groaned audibly. This small moment illuminated a familiar critique of Prospect.6: If New Orleans is the first and most enduring audience for Prospect, then the triennial cannot seek to explain the city to itself.

This awkward attempt to explicate the preservation of Black joy along an eroding coastline missed the lessons Ruth Owens offers in Black Delight, An Ecopoem. Owens’s work succeeds because it lets the viewer inhabit the balance of precarity and tenderness, without explanation. Her dual scenes reveal how joy and mourning are held separately yet simultaneously, each feeling deepening when given its own space. To exist on the edge requires art—not as commentary, but as a vessel for all the feelings that come with navigating earthly extremities and loving in the face of loss. So, Hurricane Katrina just can’t be at the party.

Every iteration of Prospect has struggled to engage New Orleans without leaving a wake of unpaid arts workers and local resentment. Even its name evokes an exploitative dynamic, recalling outsiders mining for profit. Despite the institution’s fraught history (and the faux pas in the bar), Lash and Patterson’s overall curatorial approach for Prospect.6 demonstrated a deeper commitment to care, weaving related epistemologies from the city itself and its mother regions and shining a vital light on shared reparative histories. Yet even as these curatorial strides were made, they unfolded atop historically weak relational grounds between Prospect and its host city.

This year, in response to almost two decades of critique, Prospect introduced the Artists of Public Memory initiative. The triennial invited Louisiana-based curators and artists to reimagine how monuments and collective memory function in public space. Curated by Shana M. griffin and Monique Verdin, Artists of Public Memory commissioned three powerful installations by pillars of the New Orleans art community: Abolition Playground by kai lumumba barrow; Memoirs of the Lower 9th Ward by Chandra McCormick and Keith Calhoun; and Nanih Bvlbancha by the Intertribal Collective of Ida Aronson, Tammy Greer, Jenna Mae, Ozone 504, Monique Verdin, and Virginia Richard. Nanih Bvlbancha, a massive earthen mound built by the Intertribal Collective on the Lafitte Greenway, reasserts Indigenous presence in the heart of Bvlbancha, colonially known as New Orleans. Built with traditional methods and embedded with prayers, soil offerings, and a Houma language dictionary, it honors the Mississippi River’s life-giving force, calls attention to disappearing lands and mounds across South Louisiana, urges protection for coastal and tribal communities, and promotes a return to balance. And yet, Nanih Bvlbancha was entirely absent from Prospect’s press tour, and Artists of Public Memory went unmentioned during the opening weekend, rendering it invisible in the most public-facing moments of the triennial and deepening the rift the initiative sought to address.

In the end, Prospect came and went, but Nanih Bvlbancha remains—a site of gathering, learning, and remembering that defies erasure, embodying right relationship and reciprocity in a landscape currently shaped by control and extraction.

Back at Sweet Lorraine’s, artist Harris took the stage to effusive applause, the band started to play, and the celebration blurred into a quintessential New Orleans night of bouncing around and following joy, which helps you lose track of time and worries, and lean into presence and abundance. Local artist Reggie Ford, who has been stewarding the revival of historically Black Lincoln Beach, has said that New Orleans keeps people drunk so they don’t ask much of the government. And yet, the city’s collective capacity for reverie offers a counterbalance to its hardest realities, as if somewhere between the lowest lows and the highest highs there exists an equilibrium that feels familiar—something akin to what we thought life would be like. As Monique Verdin, one of the co-curators of Prospect’s Artists of Public Memory, said, “New Orleans is not resilient, we have just found strategies for survival that allow us to mourn in community, to hold each other close and to dance in the dark times.”

Up the street from Sweet Lorraine’s sits New Orleans native Ashley Teamer’s sculpture Tambourine Cypress. Teamer’s work shares the same spirit as Harris’; both practices are rooted in the act of cultural preservation. Positioned between the Claiborne underpass and the adjacent Congo Square, the sculpture suggests a passage between two spaces central to New Orleans’ Black tradition of celebration as resistance. The sculpture is a musically formed cypress tree with cymbals as leaves, wind chimes swaying like Spanish moss, and low branches that each end in a tambourine—an instrument chosen for its deep cultural resonance, which links Black American music traditions with Indigenous rhythms and global expressions of sound. The tambourine branches are at accessible heights for both children and adults to play, allowing people to physically connect with New Orleans’ musical history by making music themselves. Inside the sculpture’s hollow trunk, two Louisiana Creole proverbs—“Water always flows to the river” and “Tell me whom you love and I’ll tell you who you are”—offer advice for the present written centuries ago. As I visited, a strong breeze made the sculpture’s wind chimes sing along with dissonant sounds from across the city: the Natchez steamboat’s calliope whistling and the white noise rush of I-10 traffic, sonically illuminating Teamer’s chosen location as a passageway. A monument to New Orleans, Tambourine Cypress is set to stand for at least seven years, withstanding the hurricanes to come and inviting people to hear the enduring sounds of a place whose legacy continues to shape the world.

Ashley Teamer, Cypress Tambourine, 2024 [photo: Alex Marks; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

Ashley Teamer, Cypress Tambourine, installation detail, 2024 [photo: Alex Marks; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

So, after the government failed us and we mourned the old world, time was carved out to celebrate life with music and community. In the context of New Orleans, the previous night of revelry was a sendoff, a different type of farewell as the sun traveled across the other side of the earth.

The final performance of opening weekend started when the sun came back to us on the other horizon. New Orleans sound artist Quintron stationed his Weather Warlock on a sliver of land along the water, facing east, where the Industrial Canal meets the Mississippi River. This place is locally known as the End of the World, named for its endless expanse of sky and water—and, perhaps, oil tankers. As the sun rose red and started to shift the wind, the Weather Warlock responded to the air, sounding like an alien radio being tuned in search of life. Gently, Quintron shifted the direction of the machine’s ears, creating a call-and-response between the wind, the sun, and the sonic manifestation of paying attention. A seagull flew by, briefly blocking the sun, and the sound wave dipped slightly, accounting for all that was animate. This ritual of attention is one way of stitching a sense of place back together, listening deeply to what can still be heard.

Quintron’s Weather Warlock. Sunday, Nov 3, 2024, 6:00 am [photo: Heather Bird Harris]

Rebirth also takes place in the act of creating something new from loss. For New Orleans–based artist Brooke Pickett, this concept materialized in 10 vibrant paintings that transform her family’s domestic possessions into monuments. To viewers, they appear like abstract swatches of bold patterns and expressive marks, but for Pickett, each swatch represents something deeply personal—a specific lamp, her son’s superhero, a sacred textile. After years spent rebuilding her home post Ida, Pickett devoted the last year to painting still lifes of items that reconstituted their home, layering thick brushstrokes to transfer meaning from physical objects to their painted memorials. This translation diminishes the original objects’ sentimental hold, perhaps in a gesture to make a future loss less painful. If she is unable to carry these items with her next time, their memory has been made permanent through months of observation, meditation, and repetition. Can you truly lose something you know by heart? One of these paintings, A Perpetual Search for the Perfect Place, suggests that if her family does leave New Orleans, it will be with the knowledge that they may not find what they’re looking for—but maybe I’m just projecting.

Brooke Pickett, installation view, 2024 [photo: Alex Marks; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn’s film Amongst the Disquiet also asks, “What makes a home when home is left behind?” Created in collaboration with singer and songwriter Thảo Nguyễn and New Orleans-based filmmaker Marion Hoàng Ngọc Hill, the two-channel film installation weaves intergenerational stories of a Vietnamese family in New Orleans, one that experienced displacement from war, rebuilt community in America, suffered a sibling’s suicide, and had a sister move to Houston in search of a better future. Told as a meandering letter from the dead to the living, the film unfolds through ethereal songs and vignettes that capture the pain of disconnection, including this haunting line: “I’m sorry, I could not bury you in the only place you ever felt easy.” Nguyễn’s storytelling dissolves the boundary between the living and the dead, making their connections feel less like echoes and more like an ever-present current just beneath the surface. The film holds the family’s overlapping griefs tenderly, surrounding them with water, like a membrane between realms.

Tuãn Andrew Nguyēn, Amongst the Disquiet, installation detail, 2024 [photo: Alex Marks; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

Looking toward ecological growth for signs of rebirth, artists Didier William and Hannah Chalew both sculpted cypress “knees,” knobby growths that rise up from the roots of the trees, typically above the waterline. The exact purpose of cypress knees remains a mystery. They could serve as physical anchors, bring oxygen to the tree’s submerged roots, or even function as a spiritual bridge between different realms. What is known is that a cypress tree can live for more than a thousand years, and the knees re-emerge based upon memory of what the land used to be.

Didier Wiliam, Gesture Towards Home, installation view, 2024 [photo: Alex Marks; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

William’s work, Gesture Towards Home, links his Haitian ancestry with the Louisiana landscape. The Louisiana Purchase would not have occurred without the Haitian Revolution, and for William, Louisiana’s land represents both a continuation of his heritage and a potential place to find stability amid displacement. William’s installation at the Historic New Orleans Collection features large paintings of cypress trees behind four towering figures that rise energetically from fabricated cypress knee bases. The figures, covered head to toe with a pattern of carved eyes, return the viewer’s gaze, guarding the trees from consumption. These trees affirm the revolutionary history often excluded from the oppressor’s textbooks, and, as William has said, they are part of his search for stable ground.

Didier Wiliam, Gesture Towards Home, installation detail, 2024 [photo: Alex Marks; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

Hannah Chalew’s installation Orphan Well Gamma Garden imagines a landscape where cypress knees and plant life have reclaimed southern Louisiana. Filling an entire room in the Contemporary Arts Center, the installation features islands of living plants; discarded oil and gas pipes; and sculpted forms made from “plasticane” paper, a material Chalew invented from shredded plastic and sugarcane fibers. These handmade forms encase the unavoidable plastic remnants from Chalew’s life as a young mother—Covid tests, pacifiers, sippy cup tops, and breast pumps—like fossils, preserved within the plasticane. At the installation’s center, a salvaged oil wellhead is transformed into a fountain, spilling black water that eerily sustains the plants, while the faint drip of a leaky pipe underscores the environmental damage left by abandoned oil wells. Chalew’s work posits that these wells, often leaching radioactive toxins for decades, turn wetlands into “gamma gardens,” a term recalling Cold War–era experiments in which plants were intentionally mutated by radiation to, you know, see what would happen.

Hannah Chalew, Orphan Well Gamma Garden, installation view, 2024 [photo: Alex Marks; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

Notably, Chalew added a HELIS logo on the wellhead as a direct critique of the Helis Foundation, a major funder of Prospect. Helis is deeply entrenched in the oil and gas industry, operating wellheads in the Gulf and participating in fracking. Chalew’s work calls out the artwashing practices of corporations that prioritize profit over meaningful environmental repair. A key part of Chalew’s practice is to avoid taking funding from such organizations, which is unfortunately difficult to sustain in the art world. “It’s the existential issue of our time,” Chalew asserted at a panel during opening weekend, urging genuine accountability for these corporations rather than allowing them to distract from their impact.

Both Williams’ Gesture Towards Home and Chalew’s Orphan Well Gamma Garden embody Adrienne Maree Brown’s concept of emergent strategy: examine what makes life successful and how we can and should mirror these strategies for our own survival. They are visual testaments to the possibility of new life and healing that can spring forth from the rupture of history, offering a chance for re-rooting, which life will always continue to do.

Hannah Chalew, Orphan Well Gamma Garden, installation detail, 2024 [photo: Alex Marks; courtesy of the artist and Prospect, New Orleans]

Notably, Nguyễn, Pickett, Williams, and Chalew, whose works are history-rooted yet forward looking, are all parents of young children. As a mother myself, I know it’s hard to dwell on decline for too long when you’re responsible for growing a new life. As Octavia Butler said, “Our tomorrow is the child of our today,” and the act of moving forward becomes inseparable from the act of nurturing. The reimagining of artists is the same work that parents are tasked with today: take the circumstances you’ve been handed, build a survivable world within it. Oh, and make it beautiful.

Lash and Patterson’s curation of Prospect.6: The Future Is Present, The Harbinger Is Home, is rooted in an understanding of change, and how relationships are necessary to weather that change. The warmth felt throughout the exhibition and opening weekend can be traced to their thoughtfully selected artists, each of whom, as Patterson noted, understands what it means to live in community, not just with it. The strength of their curation also highlights the power of placing artists such as Patterson in genuine leadership roles, where care for artists’ growth is prioritized, which reinforces the relational impact of both curators’ work. Their collaborative approach gives the triennial resonance, elevating the themes of care by putting them into practice.

So, where do we go from here? Back at the CAC panel, Mel Chin was asked about what growth would look like for him. He responded, “I always said, I’m just trying to become an artist, but now I want to grow out of it. We don’t have to be what we thought we were supposed to be. To critically look at the frame in which I’ve encapsulated my life—maybe that frame needs to be destroyed.”

Scientists are questioning the efficacy, too. A New York Times article written in 2023 by a climate scientist started this way: “Staggering. Unnerving. Mind-boggling. Absolutely gobsmackingly bananas.” They’ve run out of words to get our attention.

It’s dire, honestly. We can only correct course through collective action, yet we are navigating a landscape fractured by deep societal divides and eroding global leadership. But something I learned recently gave me a shred of hope: systems theory says that collective action can happen only by affecting cultural change—an intuitive, widespread transformation that reshapes how we live and act, simply because it’s just what we do. Culture is the work of artists, and some of the best have been given a microphone by Propsect.6. In doing so, Prospect.6 threads multiple hard truths together into objects that can speak louder than any individual story. It behooves us to pay attention to this work, and to allow ourselves to be changed.

Heather Bird Harris is an artist and educator based in Atlanta. She is sometimes a curator and writer, former middle school principal, and curriculum consultant focused on anti-racist history education in public schools throughout the South. Her practice explores the throughlines between history and ecological crises, engaging with communities, scientists, and site-specific materials to investigate possibilities for emergence.

References

| ↑1 | 61% of Americans opposed sending aid to Israel in June 2024, according to a CBS news poll. https://www.scribd.com/document/740568401/Cbsnews-20240609-SUN-NAT |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | [1] Sweet Lorraine’s Jazz Club celebrates 60 plus years of business by the Sylvester Family, Vincent Sylvain, The New Orleans Agenda 2009 |