Philip Glass: Frontiers of the Acceptable

Share:

Composer Philip Glass, Florence, 1993 [courtesy of Pasquale Salerno and Wikimedia Commons]

***

This interview originally appeared in ART PAPERS January/February 1991, the magazine’s 15th-anniversary edition. The text has been reproduced on artpapers.org exactly as it appeared in print in 1991.

***

Having celebrated its premiere in June as part of the Charleston, SC, Spoleto USA Festival, Hydrogen Jukebox is a 2 1/2 hour-long piece of contemporary music whose primary collaborators are composer Philip Glass, poet Allen Ginsberg, and artist-designer Jerome Sirlin. The title of the piece was taken literally from the lines of Ginsberg’s Howl, which became a manifesto of sorts for a whole generation in the late 1950s and early ’60s. This modern opera “live music-video” performance gives us the “eye-songs” of the atomic age, the orchestrated underbelly of what is truly America.

Philip Glass, one of the world’s most celebrated New Music composers, is also one of the founding fathers of the minimalist movement. A composer who defines his work in terms of its collaborative content, he has written for opera, orchestra, film, theater, dance, chorus, and his own group, the Philip Glass Ensemble. Probably best known for his trilogy of “portrait” operas which include Einstein of the Beach, Satyagraha (which depicts the younger Mahatma Gandhi), and Akhnaten, Glass has also worked on major collaborative pieces with such artists as filmmakers Godfrey Reggio (Koyaanisqatsi, Powaqqatsi) and Errol Morris (The Thin Blue Line), writers Doris Lessing (The Making of the Representative for Planet 8) and David Hwang (1000 Airplanes on the Roof, and choreographers Twyla Tharp and Jerome Robbins. As a prolific recording artist, Glass is perhaps most well known to the general public for his recording Songs from Liquid Days (1985, CBS Records), which features lyrics by Paul Simon, David Byrne, Laurie Anderson, and Suzanne Vega, as well as vocals by Linda Ronstadt.

Thomas Rain Crowe: Themes of truth, balance, and reverence for nature seem to not only predominate, but repeat in your work. Some might see these as spiritual preoccupations. Could you speak a little bit about these themes and about how they may, or may not, lie at the center of your work?

Philip Glass: Well, you know, at a certain point I began to see that music with subject matter is the way I work. There are a lot of different ways of categorizing composers. Some of them write or improvise music. Composers are sometimes classified as being either “serious composers of music” or “composers of pop music.” There are composers who work with music in abstract ways and still others who work with music as it is connected to subject matter.

Let’s rephrase your question and make it: “What inspires you to write a piece?” Many composers simply want to write Symphony #3 or Symphony #4, or Quartet #14, or their 3rd Piano Sonata. These kinds of composers are inspired by the language of music itself and their own development of that language. Then, there are others for whom the inspiration for writing music has nothing, really, to do with music—or at least that is how it would appear. For them, the subject—like social change through nonviolence or an ecologically balanced environment—inspires and dictates the direction of any new music. I happen to be one of a rather small number of composers who are so attracted to subject matter.

By and large, composers with a strong interest for subject matter end up working with the theater. When I first began working in the theater in 1965, I started out with experimental companies, working in a somewhat literary tradition with people whose work was inspired by Becket, and even Brecht—whose work was a little more involved with social consciousness, even though not in ways that would be recognizable as such to use today. It was really when I began working on my own pieces in the mid-’70s, beginning with Einstein on the Beach, that I really began to think seriously about just what the pieces were about. When you start to write an opera, you realize that even a small piece like Hydrogen Jukebox can take about a year and a half to do, and a large piece may take as long as two to three years. So, for me to spend that much time working on a project, it has to be about something that’s important to me. For example, I worked with Doris Lessing on a music theatre piece based on her book The Making of the Representative for Planet 8. It’s the story of a civilization which is living on a planet which is about to enter an ice age. The whole book is about how the people of Planet 8 address the question of survival. Of course it’s clear from the outset that this is an allegorical story and all the things that come up in the story are things that have to do with the world we live in today. There are very many of us here on our planet in the year 1990 who think that we could very well be on the edge of a disaster or even a catastrophe of global proportions. So we worked together for almost three years preparing this piece which absorbed a lot of my time, yet it was possible for me to do that with an unflagging interest. I never got tired of working on it because the issues seemed so urgent. So important were these issues that it went beyond my interests as an artist and how I develop, and became a project embracing a much larger social context.

As I get older, I find more and more that in order to gear up to do the big pieces, I really have to feel that this is something that has that much scale to it, that has that much weight to it. For instance, I did another piece not too long ago with a filmmaker by the name of Earl Morris called The Thin Blue Line—which is a very simple film, in a way, about a man who was wrongfully jailed for a crime he did not commit. This is a case of injustice to only one person and is not the scale of the film I did with Geoffrey Reggio called Koyaanisqatsi. Koyaanisqatsi is a film in images—without words or characters—which is presented as a portrait of America as it experiences the impact of a new high-tech society and culture. It is a film about a whole society coming to terms with a new way of living. This was a small project in that I was only involved with it for four or five months. But even the small projects, for me to get interested in them and do my best work, have to have something compelling about them in terms of subject matter.

It seems to have intensified as I have gotten older—this need to find a point of departure for the work. A point of departure which springs from a concern for the world I live in in a very ordinary way. Hydrogen Jukebox was an ideal project in that way. Allen Ginsberg’s work has ranged and roamed over these subjects for 35 years. There’s no one who has been more at the center of the major issues of our time than Allen—to the point that things that seemed so radical in the ’60s almost now seem like mainstream issues.

TRC: There’s an idea that there is a direct sympathy between sound and color and language. And that this “sympathy” or synchronicity applies as well to music and dance. If Beethoven’s 5th, for instance, were somehow translated, note by note, into any spoken or written language, what would that “poem” say? What would the painting look like? How would the dancer dance?

PG: Yes, this is an interesting idea that others have had, too. Scriabin, for instance, had the idea of the association of color with music.

My work, generally speaking, is collaborative. So I’m working with other artists all the time in similar kinds of ways to the things you’ve mentioned. With dance, design, literary sources—as well as with light in the form of lighting techniques. All the music theater work I have done up to this point includes all these things. So, you might say, I’ve been placed in an opportune way to see how that happens.

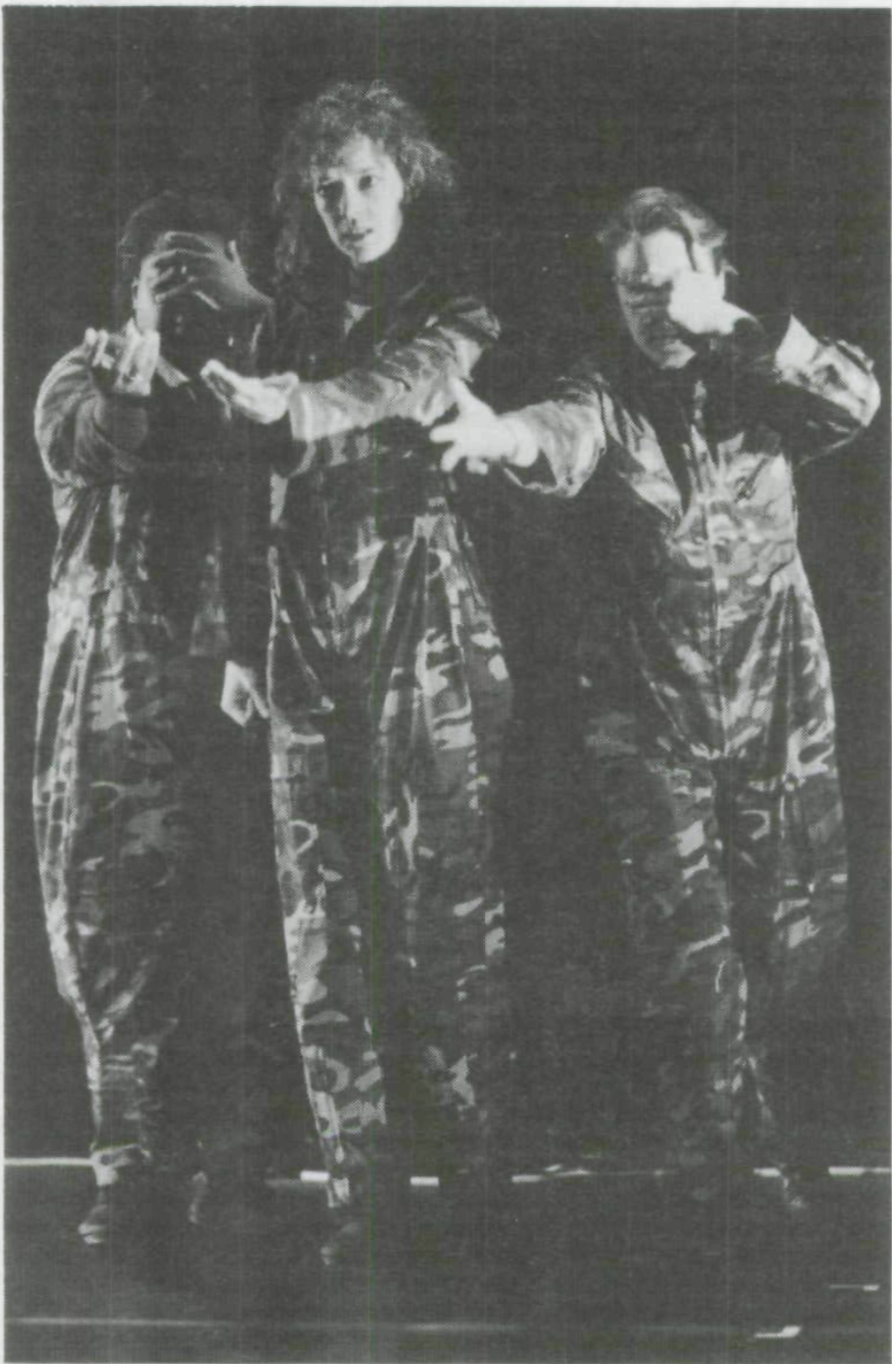

A scene from Hydrogen Jukebox (1990), Charleston, SC [courtesy of Spoleto Festival USA; scanned from ART PAPERS January/February 1991]

And my personal view of all this is that very often these things are contributing aspects to a total work and that by themselves they don’t really “do it.” What we look for in a theater piece when we bring these things together is something that is more than the sum of its parts. In that sense we’re not looking to merely reinforce things. In other words, I don’t look for a visual complement that reinforces a musical statement. I’m usually looking for something that is different, that actually heightens the music and heightens the image at the same time because they are different and not the same. This happens in film all the time.

Let me give you an example of what I’m getting at. Again, with the film Koyaanisqatsi, there were scenes where the music and images act on each other to activate different aspects without actually complimenting each other, or, as I say, reinforcing each other. For instance, easily on in the film there is a scene where you see these huge airplanes floating down onto a runway. Floating in the air. This is directly followed by scenes dominated by tanks, warplanes, and cars. This was a section of the film we called “vessels”—meaning things you travel in, like a boat. Writing the music to go with the visual images of the planes, tanks, and the cars, I decided to concentrate on one aspect of those things. Looking at the plans, I took the idea of “lightness” and I set it for voices. So, in the finished product, the opening scene with the montage of the airplanes is done to six-part a cappella choir. So I took one aspect of the image, which was the image of floating, and created a musical that, to me, insinuated floating. But I could have done it in many different ways. There are other places in the film where I did reinforce the images directly. Later on in the piece there is a whole segment of rapid movement of a variety of things. Here, I used a very rapidly moving music. A very simple one-on-one association was used in this case—a musical technique mirroring a visual technique. But, as I have said, you can also work against something as a way of reinforcing it. There is a way of reinforcing something by similarity and there is a way to reinforce something by dissimilarity. In other words, you can go with the image or you can go against the image. In Hydrogen Jukebox we have used this technique of dissimilarity quite a bit. In fact, very seldom did we use the complementary approach in combining all three elements of the piece.

But to get back to your question—it may be that these seemingly dissimilar things are actually saying the same thing, but in different mediums. But, when you put them together it’s better not to treat them that way. In other words, even if it’s true, if all they do is reinforce each other, you end up with an overwhelmingly one-dimensional work. Let’s say that a certain color combination may give a certain emotional ambiance—the fact that they’re the same or at least similar to each other doesn’t mean that they go well together. They might not go well together. In creating a performance piece such as Jukebox, you really have to entertain the whole range of possibilities.

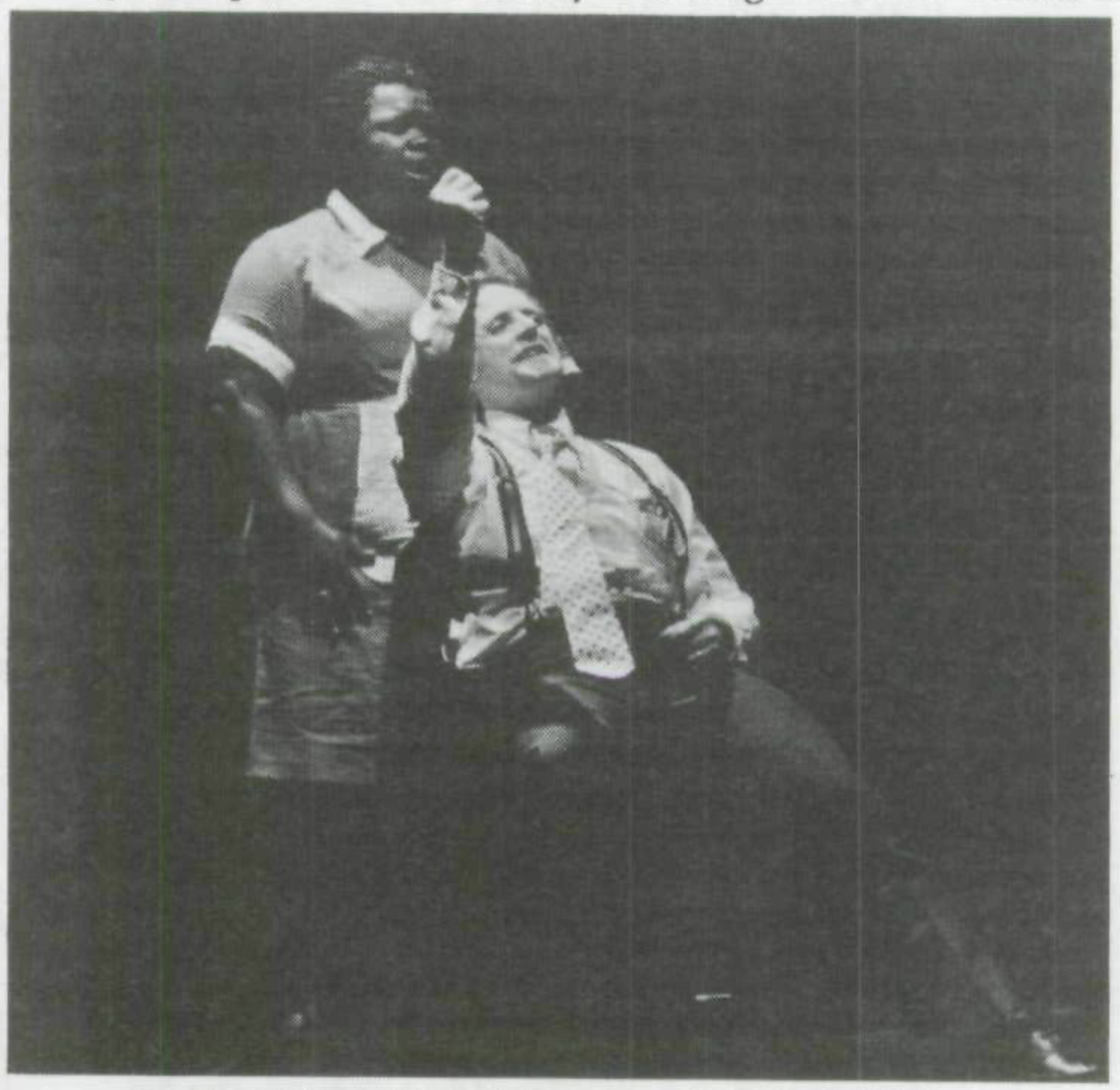

A scene from Hydrogen Jukebox (1990), Charleston, SC [courtesy of Spoleto Festival USA; scanned from ART PAPERS January/February 1991]

TRC: All this talk of similarity and dissimilarity as a means of combining and unifying things brings to mind some recent advances in physics, in both unified field theory and chaos theory. Do you see any relationship between these developments and advances in your own work?

PG: Well, I think you might be stretching it a bit, but there is something in what you say. Let me answer you this way: when we began with the idea of Hydrogen Jukebox, Allen might have come up to me and asked: “Why do you want to take my poetry and set it to music?” This is a good question. In fact, Doris Lessing did say this to me. In her case, it was: “Why do you want to take my novel (The Making of the Representative for Planet 8) and make it into an opera?” What both Doris and Allen are asking is: “What are you doing for the work?” What I said to Doris in response to her question was: “I can do things in the music that you can’t do in the words. I can describe things that your words describe, but I can do it in a way that the words can’t do it.”

In terms of Allen’s poetry—I am reminded of a writer by the name of Edward T. Cone whose book I just recently finished. In his book on “words and music” he says when you set words to music you are making on interpretation of all the possible interpretations. And so, in a certain way, you are limiting it. You have defined it in a way. But, on the other hand, he goes on to say—and this is the point that I wanted to get to—he says that what you get, instead, is a vivid presentation. Something more vivid than either the music or the text would have by itself. The word “vivid” is central to the appropriate response to this question. It comes from the word “vive”— meaning “to live; liveliness.”

TRC: Would this include the idea of “epiphany”?

PG: Well, epiphany is certainly a part of vividness. Hopefully, though, epiphanies are rare birds—not flying into the room every day! I’ve had a few artistic ones, and I’ve talked to Allen and he’s had some. Most artists, in fact, will tell you about epiphanies they’ve had. Realizations that have come out of a heightened experience, a heightened emotional experience. And the vividness of that can last as long as twenty or thirty years. You, on the other hand, may try and create through your own art form an epiphany that you had when you were a child. Actually, that’s literally what happened to Allen—he had an epiphany, a vision, in his early twenties and he says that much of his writing is an attempt to recreate that.

But to get back to your original question … What music can do in a general way is to heighten our emotional sensitivity and awareness. And when applied to a particular subject, it can bring that heightened perception to the subject itself. So, if I set a poem of Allen’s to music, from that point on, you, as the listener, might remember that poem more easily because it may have a whole emotional world attached to it, now, through the music.

TRC: My experience with your music is that there is a kind of contradictory calm, an impending groundedness, amidst the inherent chaos and implied stress in some of your scores and albums. How would you react to this assessment of your music? Or maybe this is the whole point of your work! Is it possible that the kind of subliminal calm I am experiencing in your work really is a conscious effort on your part to create an “eye of the storm” phenomenon which may in some way be something of a psychic directional marker for the masses?

PG: I’m having a little difficulty with your question in the sense that it implies that the object of my intentions as a writer and a performer is didactic in purpose. That the conscious purpose foremost in my mind is that music and the creation of music is somehow primarily a teaching role. And even though this may be functionally true in some ways, the bulk of my intentions is much more innocent than that. What I do and the way that I go about it has to do with my own perceptions about such things as social issues we were talking about earlier. Luckily, I would say, a lot of people are also attracted to it—and in this way some of my pieces may synchronistically become kind of teaching vehicles in some way for some people.

Again, a good example is the film Koyaanisqatsi. The reason I became involved in making the film is because I was very interested in what Godfrey Reggio was doing. It was fascinating for me, personally. I got involved because of this interest or fascination, not because I thought it could or would change the world. As it turned out, I think that the film does have some redeeming social value, and so was helpful to the “cause of heightened awareness,” if you will.

I think maybe it’s important to say here that I am, also, in the same position as the listener. I’m not that different from the listener. In other words, what I am exposing to myself can very often be new to me. I’m not proceeding from a position of knowledge that I am giving to other people. I’m proceeding from a position of ignorance, which I am overcoming like everyone else. When Godfrey and I went around for a time talking to people about the film Koyaanisqatsi, people were always talking asking him what he meant by this what he meant by that, referring to the film. He was always careful to respond to these questions by saying, “Well, you know, the question is really more important than the answer. I can frame the question, but I don’t know the answer.” Although he saw some of the problems of the impact of high-tech culture on contemporary society, he was quick to say that he didn’t have any answers to these questions. He was very careful not to set himself up as some sort of Messiah. And I think that we try and do that in this culture to our heroes—we think that they know more than they can reasonably be expected to. I think that kind of modesty is appropriate as an honest assessment of where we both were in relation to the making of the film.

So to get back to your idea about the calm of centeredness in my music and whether or not that is meant to be a sign to other people—as I say, the music doesn’t proceed from the idea of the sharing of a greater spiritual insight. I’m in the same position as everyone else in that I am trying to break through my own limitations. And what you are seeing in Einstein on the Beach or Hydrogen Jukebox is me doing that.

TRC: In Music by Philip Glass, you speak of “going beyond what we expect of ourselves.” Can you talk about the importance of that?

PG: I don’t know if I’m bending the subject to current affairs here, but right now, so much of what’s disturbing to artists is the issue of the enemies of the National Endowment and free expression in the arts. In our community and in our society we have people who are very much afraid to “go beyond themselves.” When artists like Mapplethorpe or Ginsberg start to work along the frontiers of what people consider acceptable, they find it very threatening. They have a hard time understanding what these breakthrough artists are doing. They think that they are actually trying to destroy the world they’re living in, and in a certain sense they’re not far off. Because what someone like Ginsberg or Burroughs or Mapplethorpe is trying to do is move the center to a different place. And this does mean breaking down the invisible borders of our minds. But here the important thing to remember is that, first of all, these people, these artists, are challenging themselves. It turns out that what they are doing may challenge other people too. But the history of art has always been that way.

We, today, only have to go back twenty years to witness these kinds of things, these kinds of public attitudes toward the arts. To go back and look at people like Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning or Andy Warhol. People twenty years ago thought that Andy Warhol was making fun of them. Not that Andy wasn’t having a good time.

So, we have in our culture the people who don’t want to change it and are afraid of the change. It’s threatening. It’s disturbing. They can barely hang on to what they’ve got and here’s some jackass who’s trying to turn everything upside down. And in a certain way you can have a certain sympathy for that kind of attitude, because not everyone has the capability of absorbing these kinds of changes. Even so, this kind of attitude is anathema to the artist as it is a direct threat to the lifeblood idea of going beyond ourselves, or what we expect of ourselves. These kinds of attitudes not only are hurdles but can become actual walls or barriers to our attempts at overcoming our own ignorance, at exploring the unknown.

TRC: I was delighted to read in your book that “the operatic tradition seems hopelessly dead, with no prospect of resurrection—but will, I suppose, be drug screaming into the 21st century along with the rest of us…” Could you explain the basis for this statement as well as anything from your experience in the theater which might support, more specifically, this idea?

PG: I tend to look at this through my own narrow point of view. But one of the big things is the collaboration—the interfacing of artists in a different way than what you find, or would have found, in the process of creating opera in the old tradition. An interfacing of artists where the artistic vision can be a spontaneous result of people working together as opposed to the kind of “master overview” of the vision of one person. We have plenty of examples of this more limiting kind of “collaboration” in the 19th century.

We, meaning my generation, are against the old operas—some of them are very beautiful. It’s just that at this point in time there doesn’t seem any point in doing them like that anymore. I don’t think we’re interested in that. In terms of process where collaboration is concerned, a lot of it has to do with technology. The new technology has allowed us, somewhat paradoxically, to bring the arts together in a way that we could have never done before. Hydrogen Jukebox is a perfect example of this, with its amplified stage projections, images, amplified music, and vocal music. During the process of making this piece, I have often wondered how, in fact, we could have even put on this piece two hundred years ago. Not only could we not have, but we wouldn’t have even thought of it! The technology available to us now gives us that opportunity. It allows us this possibility.

I don’t think that you can underestimate the effect of technology on artists today. It’s literally opening up and determining new ways of working. I don’t think that we’ll ever go back. And in truth, you can’t ever go back to old forms.

How technology has impacted my work personally is that when I work as a musician I have two or three people that work with me. There is someone who works as a music director, who works on synthesizers developing sounds which are tailor-made for each new piece. We work together developing the technology for the sounds. I simply don’t have the time to do all this by myself. The man-hours involved in mastering these technologies is beyond what one person is capable of doing.

It’s probably not stretching it to make the comparison that what is going on today in music theater is comparable to collaborations during the Renaissance, with small armies of artisans and apprentices working together to produce these large scale performance events. In the case of my work, these people with whom I work are not apprentices, but coworkers working with me to create new pieces. Koyaanisqatsi, again, is a good example of this. If you pay attention to the credits for this film—they go on for about 4 minutes! While this film might be the vision of only a few people, it is not the complete work of only those few. It is the work of many. And through this process it becomes, finally, a vision that is shared by many.

I think that the movement toward collaborative work has mainly to do with vistas of technology and the simple fact of man-hours and man-power that’s needed to dominate the technology and make it work the way you want it to. I dare say that one person could not have accomplished the work that I have done. It does take a group of people. People are always asking me, “How do you do so much work?” and I say, “I don’t.” I have a bunch of people I work with—up to a dozen. Practically the only thing I do alone is at the beginning of the day when I sit down by myself to compose. Otherwise, I’m working as part of a team.

Writing the score is the beginning of a long road which will finally lead to a production. The ability to coordinate these new forms, to bring in people, to work with a visual artist such as Jerome Sirlin, or a lighting designer who can work miracles when you need them, all becomes part of the extended work of “composing.” Of putting together the pieces of a total production.

I think we’re pushing more and more towards something which I think for us has become an ideal—which is a kind of collective work. Where art and technology work hand in hand. And through the labor of all these people working together, a piece like Hydrogen Jukebox is possible even though it takes an enormous amount of collective and individual talent. It’s impossible to conceive of doing something like this in any other way.

Music theater has, I believe, become the performing art of choice of the theater-going public. 1000 Airplanes on the Roof went to 70 cities. We did 150 performances in 18 months in 55 cities in America which included a performance in North Carolina. We couldn’t have done such an extensive tour with this recent piece were there not the support from people attending the performance. Hydrogen Jukebox, I expect, will also travel around the country. Our limitations now are not audiences— the audiences are there—but the question of how portable we can make the piece and get it on the road. How to get it into a truck and how to get the set built in 18 hours so we can do a show in one city one day, then move to another city the next day. But the public is there. The appetite and interest are there.

TRC: You have mentioned in numerous interviews over the years and I believe in your book as well that in the early 1970s, theater—specifically the work of Brecht and Beckett—had a profound effect on your music. For me it was, early on, dance—and therefore the “movement of language”—that inspired and excited me. Then it later became music (rhythm) largely inspired by my experiences of Native American drumming and singing that began to fire my words. What is it now that might have such a formative effect on your thinking or on your creation of music?

PG: When I was younger it was the visual arts that caught my attention. I was mostly inspired by painters and sculptors. Later, like yourself, by dancers. Now I’m actually more interested in writers. I’m coming around to writers, to people like Allen Ginsberg and Doris Lessing and even some younger writers. I’m discovering a new magic in poetry and language that is finding its way into my music. For the last couple of years I’ve been working almost exclusively with writers on major collaborative pieces. This past year, for example, Allen and I have been traveling around the country performing together as something of a side-line to this larger work we have been working on called Hydrogen Jukebox. I’m beginning to find (as Edward T. Cone says in his book) that it’s true, at least for me, that music and language are inherently similar and compatible in ways that are not only interesting, but inspiring. And so this is the direction my work has taken.

TRC: There’s a whole new generation coming up now since your first performances and the advent of minimalism and New Music. Can you tell what will be the “new” music of the 21st century?

PG: In terms of what direction I see music taking, for one thing I think it will continue in the area of mixed media. The sort of things we’ve been talking about. One of the things that is happening to bring this about is the fact that the technology is getting cheaper. I think you’ll find in the near future that the reaction to all these big pieces we’re doing is to see smaller, easily affordable pieces done in new ways. One of the things that’s going to happen is that because of the increasing affordability of this new technology, it will become possible for new artists to make pieces out of their own apartments and backyards, and be able to travel easily with these pieces. Even now, there are younger composers in England who have virtually made recording studios in their apartments for as little as four or five thousand dollars. Sampler, tape machine, keyboard controller, and they’re off! I’m also seeing people beginning to put together theater companies where before the costs for such ideas were restrictive. So what has been missing in the past 20 years or more has been the means for young people who don’t have the means to start. Which is what I did.

So with the new affordable technology, these younger composers will develop new techniques and a new kind of language to go with what they can do with this new technology. I’m already beginning to see this happen. That there are new musical and theatrical levels developing around these kinds of guerrilla-stripped-down outfits. And it’s interesting. And what will happen to them as they acquire the means to expand will be interesting to see. But there are already a lot of places in the New York area where you’ll see young people working with very sophisticated equipment that they have been able to get their hands on with very little money. So I think we’re going to see a reaction to all this high-tech stuff, but in the context of a new kind of technology. Still high-tech, but simpler. Portable. And I think that there is a tremendous amount of room in the future for gifted and imaginative people to still be able to work.

***

This interview was selected for online publication by Fall 2020 intern Phoebe Liu. A journalist and musician, Liu enjoys writing about artists and their work, and the intersection of visual art and music. She has worked with the Sacramento Bee, Yale Daily News, and Appen Media Group. She is currently a student at Yale University.

Thomas Rain Crowe (b. Chicago, IL, 1949), as a poet, has collaborated with musicians, dancers, actors, visual artists, and other writers in producing performance pieces for over 15 years, including a music theater ballet-opera, Metamora: The Eyes of the Butterfly, which premiered in 1987. He currently lives in Cullowhee, North Carolina.