Patty Chang: Milk Debt

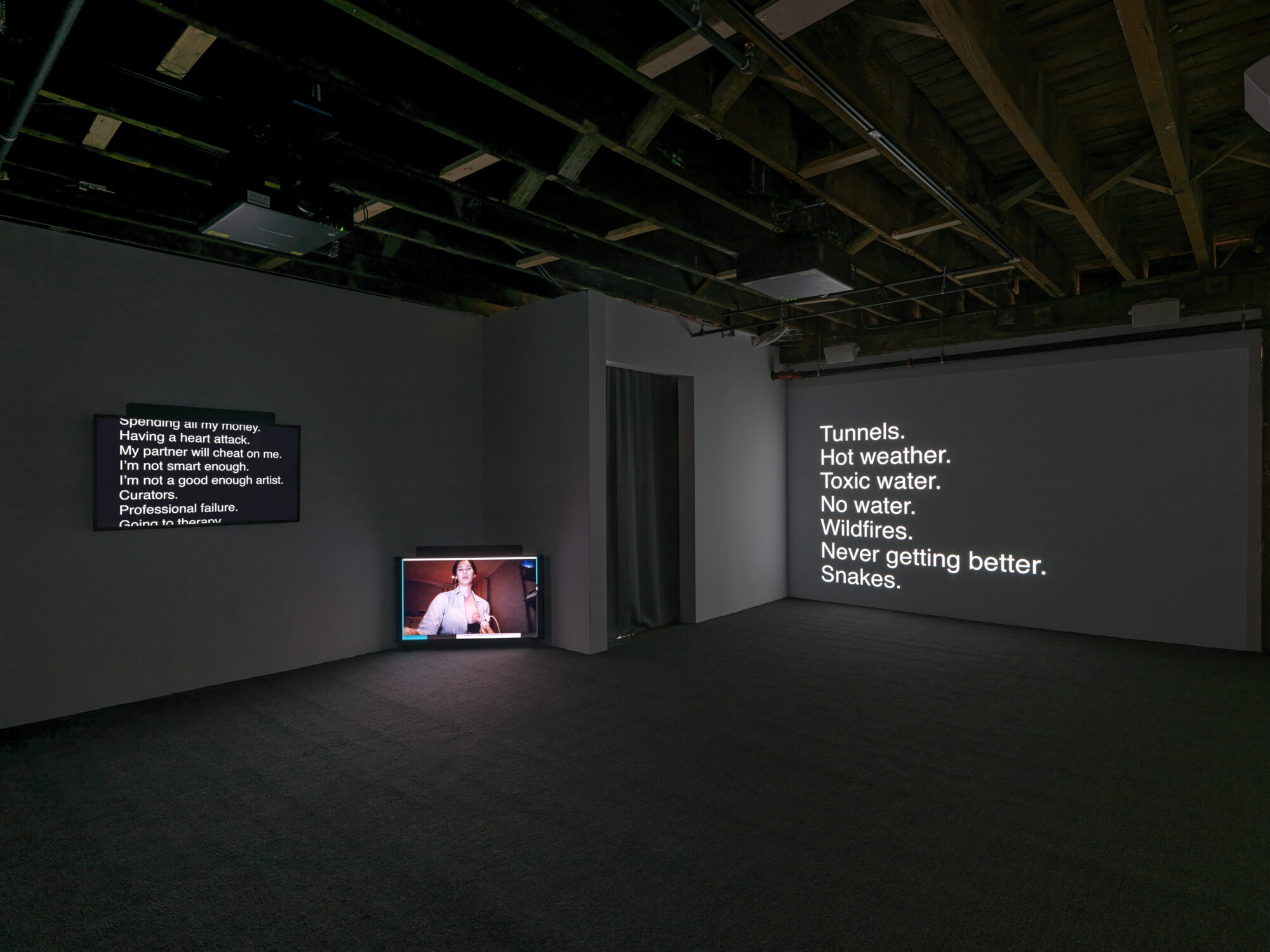

Patty Chang: Milk Debt, installation view, 2021 [courtesy of Pioneer Works, New York]

Share:

Death.

113 degrees, everyday.

Water running out.

Loss of meaning.

sharks in the water when I see a seal.

lemmings.

These are just a few of the grim, humorous, and relatable fears that make up Things I’m Scared of Right Now (2018), a list written by artist Patty Chang after she moved to Los Angeles. It became the basis for her video installation Milk Debt (2020), in which nine women pump breast milk while reciting a list of fears solicited by Chang in an open call. The work is tender, affecting, and expansive, both archive and barometer of this moment.

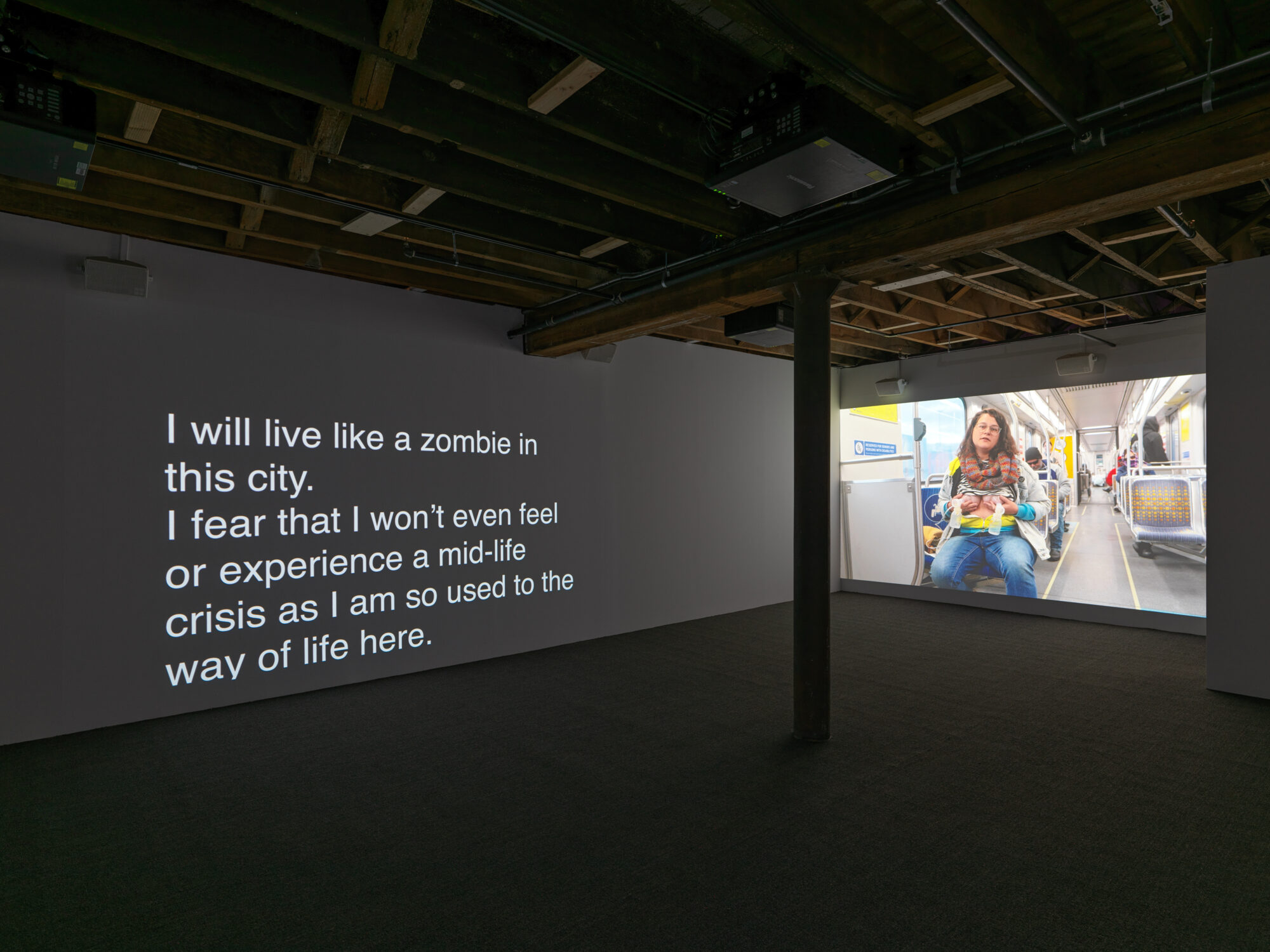

As many as five screens flicker on and off in Milk Debt, with different videos playing simultaneously. The list, typed in a large sans serif font against a black background, occupies one screen and sometimes more, and scrolls by like a teleprompter of dystopia imagined and reimagined. Still, Milk Debt is far from menacing or angst-ridden. Chang directed each actor to “just read like you’re reading a list.”1 The result is a blasé performance that washes over the viewer in a pleasant wave, at least until the implications of the text sink in. Even then, each statement follows the next without time for deep contemplation, an effect compounded for the viewer by reading the text while hearing multiple women speak out of sync. Although the list can be organized into broad categories—climate change, politics, health and personal relationships, financial worries—the effort to remember specifics is like cupping water and watching it stream away in shallow rills.

Patty Chang: Milk Debt, installation view, 2021 [courtesy of Pioneer Works, New York]

Chang has worked with fluids—in literal and metaphorical form—for much of her career. During her travels in Uzbekistan, Chang created Letdown (2017), a series of photographs of her own discarded breast milk. The act of dumping breast milk into the environment “collapsed into the [same] representational space” Chang’s lactating body, depleted of milk, and the Aral Sea, a geographic body shrinking thanks to extensive irrigation.2 Photographed next to crumpled bits of paper, dirty cutlery, and heels of bread, breast milk registers in Letdown as abject, debris to be thrown away. Though Milk Debt also explores movement and bodily fluid, the significance of the milk differs. The whoosh of the performers’ pumps is as regular as a heartbeat, a reminder of milk’s purpose to sustain and nourish human life. The visibility of the pumping mechanism, clad in clear plastic and accompanied by zippered cases, further emphasizes the fluid’s status as a valuable and harvestable resource.

Patty Chang: Milk Debt, installation view, 2021 [courtesy of Pioneer Works, New York]

Central to the work is the tension between extraction of a finite resource and that which flows, unrestrained, outside the vocabulary of capitalist extraction. The title Milk Debt comes from a term in the late David Graeber’s book Debt: The First 5,000 Years (2011), which refers to a Chinese Buddhist belief that the value of a mother’s milk can never be repaid by the child. But, as Graeber notes, the difference between debt and other forms of obligation is that the former is quantifiable and thus transferable. “Milk debt,” then, is something of a misnomer. The exact amount of breast milk produced by a lactating body is almost impossible to measure, a resistance to quantification underscored in Milk Debt. In one part of the work, actress Kestrel Leah sits in a tub and pumps directly into the bathwater, which turns into a murky solution of diluted milk—waste that has neither use value nor exchange value. Another woman lactates near a stream where water gushes past rocky banks. Milk Debt draws attention to this flow of liquids, slippery and elusive, that challenges the vise grip of collection and exploitation.

Patty Chang: Milk Debt, installation view, 2021 [courtesy of Pioneer Works, New York]

Of course, to take the title at face value would be to miss what’s at stake. Milk is a metaphor for care, which hinges on the specificity of social relationships and the obligations needed to maintain intimacy. Debt is impersonal, obligation interpersonal. To pump breast milk is more than to transfer a resource; biologically, the activity bonds the mother and infant by producing oxytocin, a hormone that stimulates feelings of love and affection. The act itself is one of care, sited in the female body.

Chang does not abstract the body, though. Rather, she locates it within messy political realities, many of which are mentioned in the list. One actor from Hong Kong staged a live performance of Milk Debt during the anti-extradition bill protests. Another actor speaks from the US/Mexico border, still others from kitchens and living rooms via Zoom. The performers serve as conduits for the fear of being deported, of becoming stateless, of losing a job. They stand in for the kind of body abused by society. Brown bodies. Black bodies. Bodies that protest. Bodies that are disabled, that are unemployed, that lack a stable home.

Patty Chang: Milk Debt, installation view, 2021 [courtesy of Pioneer Works, New York]

Milk Debt channels our anxieties about the future into a generative discussion about what we owe one another. But where do we start? Milk Debt centers the female body as a site of care that is specific and political. In doing so, Chang seems to echo Adrienne Rich’s exhortation: “Begin, though, not with a continent or a country or a house, but with the geography closest in—the body …. Begin, we said, with the material, with matter, mma, madre, mutter, moeder, modder, etc., etc.”3

References

| ↑1 | Patty Chang and Malvika Jolly, “New Social Environment #284: Patty Chang with Malvika Jolly,” The Brooklyn Rail. Video, 00:31:16, online. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Chang and Jolly, 00:23:26. |

| ↑3 | Adrienne Rich, “Notes Toward a Politics of Location,” Blood, Bread, and Poetry: Selected Prose 1979–1985 (NY: W.W. Norton, 1986), 213. |