Operating Along Desire: Derrick Woods-Morrow

Film still from Much Handled Things Are Always Soft, 2019 [courtesy of Derrick Woods-Morrow]

Share:

Derrick Woods-Morrow’s photographs and video installations feel like a simultaneous invitation to the past and the present. The warmth, sensuality, and community captured in his images represent a sliver of the abundance he embodies and arranges.

Often black and white, the works are reminiscent of serene visuals from Julie Dash’s 1991 film Daughters of the Dust. They evoke purity and spirituality juxtaposed with disruptions of gender binaries in the American South. Derrick and I met over Zoom to discuss the concepts that guide his current work, the necessity of institutional partnerships, and the creative and personal challenges of working in art.

Much Handled Things Are Always Soft (still), 2019, short film, original duration 8:36 minutes [courtesy of Derrick Woods-Morrow]

Tyra A. Seals: When coming across your work on Instagram, the intimacy and vulnerability were a really impressive, magnetic draw for me. I’m curious what propelled you to begin capturing moments like that and what they signify for you, especially in a pandemic, when we have to rethink how intimacy functions and what spaces allow for intimacy to take different shapes and forms.

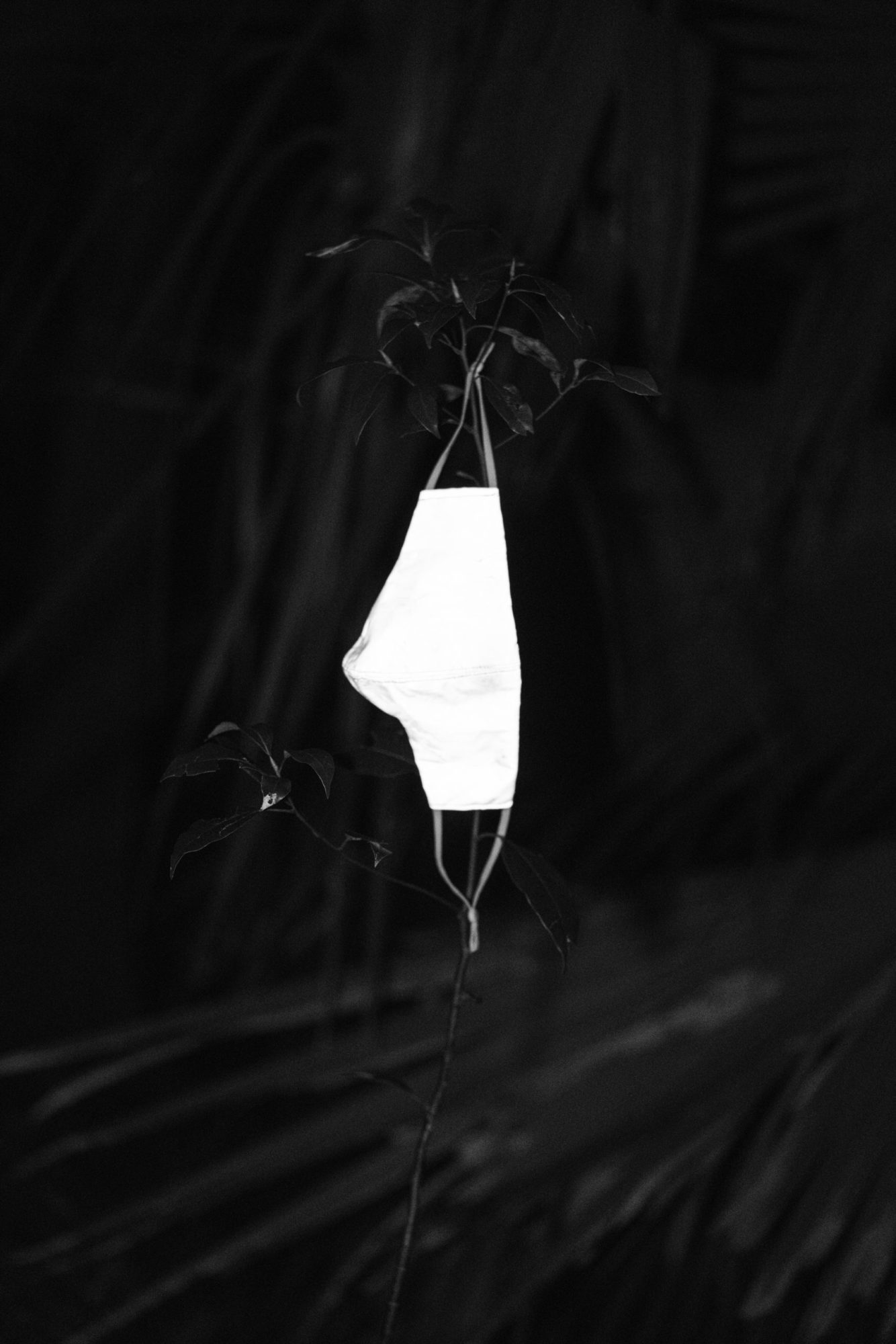

Derrick Woods-Morrow: It’s a process. It’s funny, because I call it selfish, and people go, “You’re not selfish.” But it may have been a defense mechanism. There’s two ways to exist in the art world, or in the world, that shield you. You can either [withhold] a lot of information and not let people get to know you, or you can—[as] a shield—be so transparent that people can’t really attack you or come for you. There’s a way that people talk about my sex life, or my queerness, the way in which I move through the world. In a way it’s all out there. I’m not shamed into not talking about the glory hole that’s sitting in my living room, which is mediating my sex life during COVID. I’m not shamed into talking about when I cry or when I don’t, or that I have a problem doing it sometimes, and whether that’s a masculinity construct. Being quite transparent, I wasn’t ashamed to openly admit—in front of my mother, who has access to my Facebook—to having 2,000 sexual engagements in 2017. There are [things] we—I was brought up in the Christian, Baptist South—just don’t do. I continue to ask myself why we don’t do them, and then do them in my art practice. That discomfort makes better work for me.

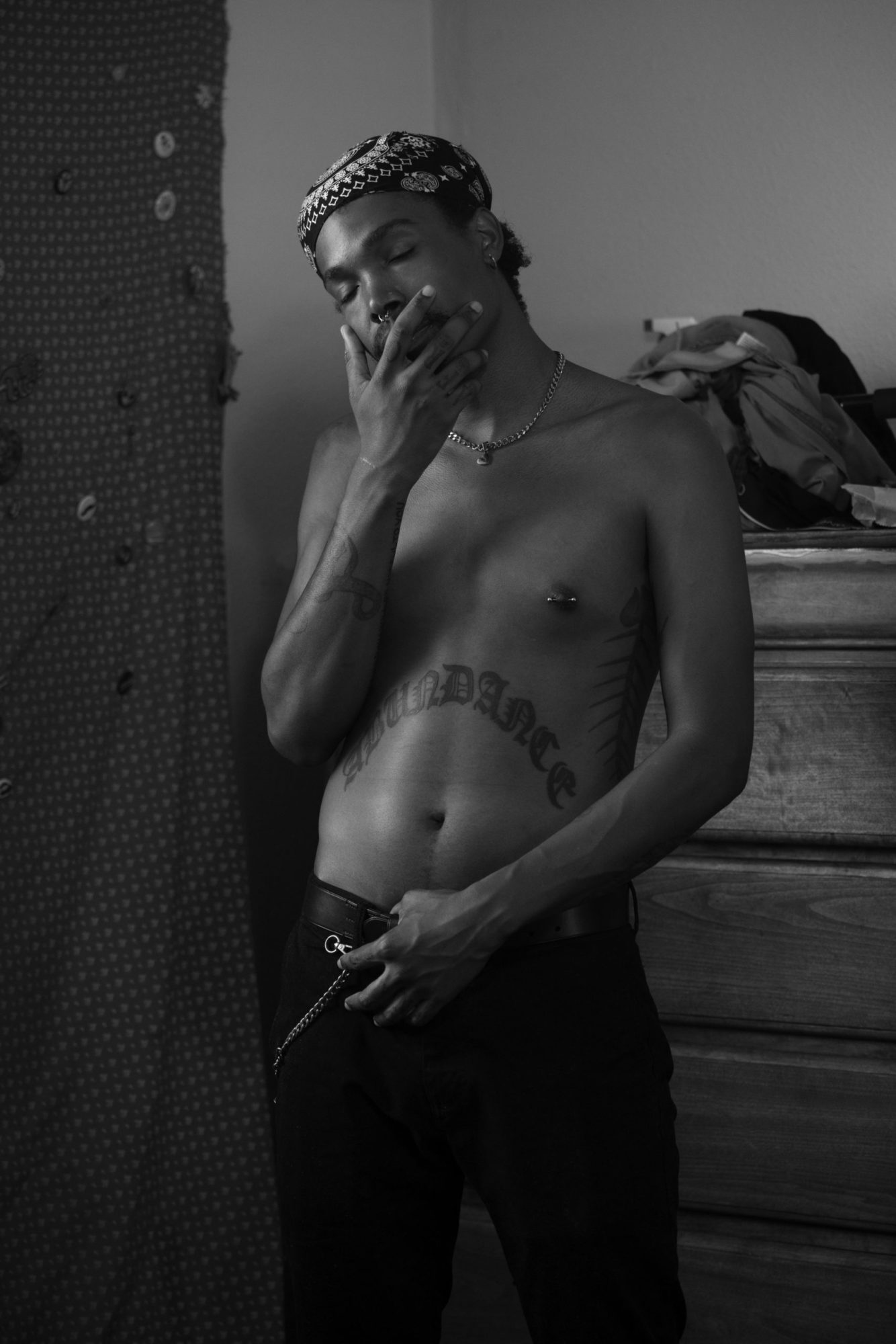

TAS: When pictured, [your subjects are] either particularly obscured, in some sort of motion, or rendered completely invisible. Why [is that] the way you’ve chosen to photograph them?

DWM: In many ways my art practice is [an attempt] to break myself down. We live in a world where the institution of art can become comfortable for Black artists, in this moment particularly, ’cause a lot of Black artists, a lot of my closest friends, are blowing up, and they’re also becoming commodities at the same time. And I’m—I guess we all are—trying to not become a commodity. But we live in a White, capitalist world. I’m really interested in the ways … we mediate and navigate the conversation of capitalism and the commodification of our bodies, of our souls, of the things we do in the world. How do you have dialogue about the Black body and Black soul and connection without it solely being—and I come out of a photography background—a document of the body or the face? How can it be more? How can the relationships we have with each other be more about the connection?

I know when I’m showing work in an institution, the work is different from when I’m showing at a grassroots space. When there’s a different movement happening in the world, like the Black Lives Matter movement, the George Floyd … assassination, that caused me to move my Instagram from a place of showcasing artwork to amplifying Black voices. Oftentimes Black femme voices—and more recently Breonna Taylor’s killing—didn’t get as much buzz at first. A lot of the dialogue that I was trying to have is, let’s build the capacity to talk about things. Making a product out of it, making an art piece out of it, didn’t necessarily get to the root of the trauma I wanted to talk about.

TAS: Being formally trained in photography, how do you consider the medium’s role in documenting this simultaneous pandemic-recession-social uprising that is powered by rage and powered by Black death being put on display? So much of this calendar year has been consumed by that, and is still going on, considering.

Jaylen (from American Intimacies – New Orleans, LA), 2021, photograph [courtesy of Derrick Woods-Morrow]

DWM: I have a love-hate relationship with the image. People commonly talk about the document, or the documentary photograph, being the most neutral photograph. I disagree. I think the viewer forgets this person has chosen a moment to document, authentic or not. It’s not a 360-degree camera, so [in] the other 270 degrees behind and around the other side of the camera, other moments are happening. To even choose to document something a specific way, it’s not neutral—it’s a choice.

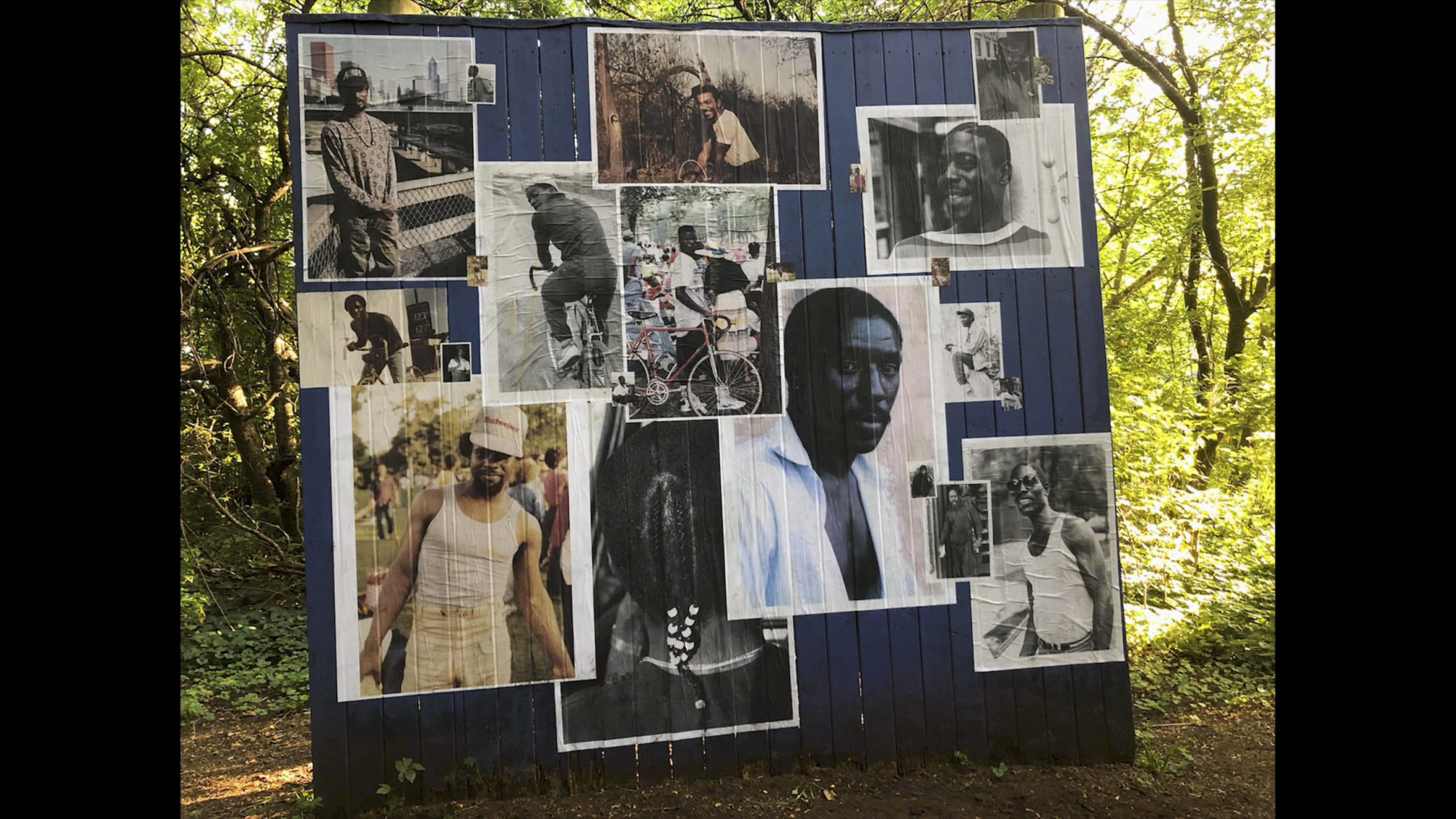

We see [that] all these images being pushed in our faces, oftentimes meant to be seen as neutral, are not at all neutral. I have to continuously ask myself, why was this taken? Who could this be serving? Why is it not serving me at this moment? As someone who’s engaged in making images, I try to expand photographs. Because I have a love-hate relationship with the photograph, I want to make it into a sculpture. Or I want to make it into a performance. I want to extend the conversation with what I see as a still moment that encapsulates so much more drama, pain, so much more happiness, actually, than you can see in a single image. In the process of spending a lot of time over the past two years documenting my experiences with Black queer people as I travel, it’s harder to think about how that functions in a society today, when the pandemic is affecting those people the most. Bringing those bodies together seems more of a danger, so a lot of that has happened via Zoom and also through amplifying the voices around me.

TAS: Have there been significant challenges, in terms of using all manner of platforms, based on what different people can access? Do you feel like that’s been informing the final product of what you’re creating?

DWM: It’s all gray matter. I think there are very positive things to an Internet world. I think—for me, in my defense—I make a lot of work that’s meant to be experienced and seen and does not photograph well. That’s why there’s not as much content on the Internet. What I benefit from is installation space, but people can’t go and see installations. Then what do you do? I think the ability to send people to an installation space via video or Zoom is really beautiful. I’m part of an exhibition in New Orleans right now at the Contemporary Arts Center, and we had a panel talk. Prior to the panel, they screened an eight-minute gallery tour. The way it was done was really beautiful. I think all the artists in the exhibition were from the South or [were] artists making work in the Gulf [region] specifically. If you couldn’t travel to see the show at CAC, you may be able to see it only through scant photographs. To have the opportunity to see it as a video is a really beautiful compromise. At the same time, I don’t know that the magnitude of the photographs or other sculptures in the space from other folks’ work can actually be understood without going to see it in person. I think a lot of us make things that people need to experience, so it’s hard.

TAS: For me, being in community with artists, scholars, and folks who want to better understand the work that’s being made—and make it accessible to those who don’t have formal training—is key, and can exist without the bureaucracy and politics of institutions. I’m definitely thinking more about how independent curatorship and scholarship can work. Granted, there are challenges, but I feel that the peace of mind that comes with that, the autonomy and agency that exist, make it worth it.

Derrick Woods-Morrow, An Impediment to Grace (as Grace Jones), 2015, archival Inkjet Print, 40 × 30 inches [courtesy of the artist]

DWM: The question oftentimes for me is, what is the necessity, and what is fueling the necessity? Where am I content, and where do I feel like I need to grow? Where have I been made aware that I need to grow? But also keeping in mind that if a structure is already in place, it most likely is not meant to benefit you. There are structures being formed by Black radical imaginative people at this moment with you in mind, but in general they haven’t existed before, because academia wasn’t kind to people like you and me. I do think if the structure already exists, it’s probably worth exploring, [as in] how it could exist differently—even if, for someone, it’s working. I think that’s a question for all of us.

There are bandwagons worth jumping on. I jump on those trains to better myself and gain more knowledge with the hope that it inspires me to develop a new way of thinking about language, and the institution I want to create. You have to … consider mental health and safety, because there are many ways that working with institutions can drain [you of] parts of yourself. It may be worth it to you, along a certain line. You just have to measure that for yourself. But the person who’s willing to measure that and say, “You know what, this White institution is going to net me $50,000, and I need that to live for the next year. And I know that it’s going to drain my mental health, and it’s actually going to be a detriment; can I compensate with these things on this end? Can I compensate with more therapy, because now I have the money to go to therapy? Can I compensate with leisure time, because I’ve advocated for myself to get a better benefits package? That’s [referencing] something that’s more stable. When you’re working with a gallery or someone who wants to sell your work then it’s, “Okay, does this build a future, does it build good bones?” I always think about good bones. Maybe it isn’t perfect, but does that help build the structure of the body of what I want my life to be? I used to say yes to everything and not, “Do you think this could help initiate something you want to develop—and how?”

TAS: It’s something that ebbs and flows. There are times when financial needs are urgent and one has to make that sacrifice. I know, in your words, it’s going to be extremely draining to deal with the daily requirements of this role or being in this space on a regular basis, but there is that necessity.

DWM: Going back to the construction of gender—the idea that, in a masculine world, you would find something you’re good at, push it into the ground, until you bully everyone and be the best at that thing. Or you could go, “Things change, people change. You’re allowed to change.” No one taught us that. Or I could make a completely different piece of artwork than I made the day before. Or I could try to deconstruct the ideas of masculinity in my own practice or in my own life. That way, I don’t have to be held to a standard that I learned was the basis of how people should function, the things I should achieve, or the ambitions that I have. Instead, the very sort of queering of masculinity, or my own expectation, is that I can set my own standard of myself, and it doesn’t have to match anyone else’s. As long as I can eat and sleep soundly, at least for me, that’s enough. Even Black people who are, like, “The world’s a mess”: I hear you, but I can only put good energy into it. It’s not my job, or any one man or woman’s job, to fix it. It’s a community decision development …. But beyond that, I want my work to matter for trans and queer folks. I want my work to matter for Black folks.

Film still from Much Handled Things Are Always Soft, 2019 [courtesy of Derrick Woods-Morrow]

TAS: Considering that, how do you feel exhibition opportunities so far have guided your professional journey? I’m curious what kinds of shifts are necessary and what kinds of edits you make, depending on institution size, and if they ever become personal?

DWM: I work best, in my opinion, as an installation artist who’s specifically interested in the space. The space can be metaphysical, can be emotional, it can be the time in which the exhibition is happening. It can be literal space, like the dimensions of a gallery. I think that’s when I feel strongest in a decision. I just installed a piece at the MCA Chicago titled How much does this moment weigh for you? It is a police car, cut in half, crushed by a car compactor, and hung from a small crane. And the thing that works on the police car is the spotlight, so as you move around the gallery the spot goes off, and as other people move around the gallery you become aware of people moving around the gallery, based on that light going off. When people leave, it goes off, so you see it hit them in the back. It’s at face/eye level. Based on the detection of the motion sensor, it hits you right there [gestures toward face] and leaves the afterimage of the spotlight in your head when you encounter it.

My choice to do that, and a lot of other things institutionally, are centered on the audience being White. The room wouldn’t be dark, or the walls wouldn’t be painted black, or the audio wouldn’t be what the audio is in this installation, if it wasn’t for my awareness of what the institution is. I’ve since tried to be immediately conscious of this [reality] since I started making work a few years ago, but I become more attuned to it each time. It’s a lot of throwing pasta at the wall and asking, “Why does it slide, why does it stick? Why is it not perfect, or is it perfect? What is perfect?” These questions continue to hit me, oftentimes …. I always come back to the feeling.

My photographs operate in a different language, but similarly, in that they’re often very dark. And it’s largely about how you come to the darkness in the photograph. Are you willing to see it and dismiss the darkness in the photograph? Are you willing to get into the photograph? Will you search the photograph for the Black body, the Black faces? And if you’re not willing to, then I don’t … I guess I really don’t care. I care enough that I want Black people to do it, but when White people are lazy and dismissive, I just say, “Okay.”

TAS: That’s fine.

DWM: I’m oftentimes operating along desire in the work. It’s true, it’s a very large part of the way I see manifesting expressions of emotion. When I move through feeling, I think the work works the best. I want people to feel what I feel, and knowing that they can’t, and the closer I feel like I can prepare an experience for that, the better I think the work is. Even if I know the failure is coming. I’m okay with it.

TAS: There’s a very specific juxtaposition of things that are considered masculine versus things that are considered feminine. Going back to the difference in what exhibition spaces of varying sizes offer, have you witnessed apprehension toward how those concepts are presented? How has that disruptive tug-of-war with gender outside of binaries been received?

DWM: Yeah, I’m like, can we talk about sex in the Black community, please? We can almost talk about gender now. Like, almost. It’s hard, because the communities and the people who I want to have the dialogue with may struggle with the Whiteness that has clouded our eyes. And the inability to connect with an artwork isn’t always the audience’s fault. But I do think that it’s in the artist’s best interest to try to be aware of the intersectional things that are happening as best we can. I work to be mindful, at the institutions [where] I’m showing, what the demographic is, and sometimes it’s a struggle, because there’s a salient, very strong juxtaposition of sartorial codes in some photographs. Very much like the dress or the garb in relationship to a male-identified body. Whether that body is actually male or not is one of my questions. But the viewer may read that body as male instantaneously and then disregard the further dialogue about why they did that, and hopefully somehow this interview or the language that comes about in a panel with the institution can help bridge that gap. I do think that the language and the conversation around the work is just as important as the work.

One night I cruised the Black maze. Swallowing me whole, tugging ever so slightly, I came into blackness. Relieved, we, blackness, and I, left our masks behind. (30°00’08.8″N 90°05’31.8″W), New Orleans, 2021, photograph [courtesy of Derrick Woods-Morrow]

Whether or not it’s perfect, misinterpretations of your work are going to happen. I truly believe in Roland Barthes’ the artist is dead. The artwork is the artwork, and people are going to interpret what they want. But I don’t expect, no matter what institution I’m at, for anyone to fully understand the work to begin with. I’m also aware that the misconstruction of the language that’s in the work is going to constantly happen. It’s allowed to change.

My second film, Much Handled Things Are Always Soft, which is a Toni Morrison quote from Sula—I think the crowning achievement of that work is that it was streamed on the Jack’d app. Jack’d being a gay social media for Black men primarily, but Black queer folks in Canada and the US with upwards of five million viewers. At a moment during the pandemic, you could go on for a week to see the film, and I saw 50,000 people from around the nation viewing my work at the same time in a way that could never happen at a gallery. That could never happen at the MCA [Chicago] in that way, and that became a language I’d love to speak more of in the future.

TAS: Having a nonlinear path is something I consider to be really crucial. I’m curious: Who do you consider pertinent figures in how your work develops? And I’m curious how you’re interfacing with those figures now being at home, and if they inspire you in different ways, if they manifest differently than they have before, and how that looks for you.

DWM: Instagram is a drug that can be really good sometimes if you know where to place it. I’m a very visual learner, and I recognize that you can watch someone else’s practice develop from afar and be inspired by their work. I can think of lots of names—Cauleen Smith, Martine Syms’ work about language and representation, Jonathan Lyndon Chase, Clifford Prince King—an amazing young photographer. Some of these folks I speak with on the regular, and some of them I don’t. Dawoud Bey and I are very close. The other day I had a question about auditioning an artwork based on an art market standard that I didn’t agree should exist. I asked him to take 20 minutes to talk me through it. He hopped right on a FaceTime instantly. I think that’s beautiful.

TAS: I absolutely love that.

DWM: There’s so much mentorship to be had, and community to be built, with the objects, with the people, with the questions that you don’t yet have answers for. I don’t assume that I know a theorist when I read their work, but that relationship begins to build, and when we cross paths in the future, I get to develop it based on that initial “meeting.” I think life is about relationship-building.

***

This interview originally appeared in ART PAPERS Summer 2021 // Speculative Masculinities.

Tyra A. Seals is an emerging curator of African diaspora art and a PhD student in the Department of Art History at the University of Delaware. Her research re-examines conversations of accessibility, material culture, and sustainability by exploring how Black woman assemblage artists have maintained and transformed their practices across generations. Tyra is a proud Atlanta native and alumna of Spelman College, where she earned a BA in English and minor in art history, cum laude, in 2018.