On the National Mall

Members of the National Guard and US Marshals Service on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, June 2, 2020, photograph taken during protests against police brutality and the murder of George Floyd [photo: Brett Davis; courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

Share:

Someone in the café car asks if she is too early for the seasonal fruit, which as it turns out is a small plastic container of cantaloupe and honeydew. The view from a train is always of the backs and sides of things: loading bays, dead ends, service entrances. In this case, as I travel between a city still in winter and another for which the early weeks of spring have already passed, it is also a sort of vernal time-lapse of the Eastern Seaboard. I have scheduled this trip to coincide with the final week of the National Cherry Blossom Festival, but I have missed the peak bloom.

In Washington that night, what’s left of the blossoms looks sharp and metallic under the flickering streetlights, as if the thin branches are clad in patchy tinsel or barbed wire. The Tidal Basin has flooded, and I follow my more surefooted sister around vast puddles in the dark. Crossing the street to the George Mason Memorial, we dodge double-decker buses from which announcements of the surrounding significance blare even at this late hour.

Lincoln Memorial When Cherries are in Bloom, c.1926, photograph : print on card mount, stereograph, 3.5 x 7 inches [courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington, DC]

On March 27, 1912, First Lady Helen Taft and Viscountess Iwa Chinda, the wife of the Japanese Ambassador, planted the first two of the more than 3,000 cherry trees that now line the Tidal Basin. We glean this “fun fact” the next day from the ballpark scoreboard between innings. Absent from the abbreviated history lesson, I learn later, are several notable personages, not least among them the geographer Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, who lobbied the government with a zeal bordering on fanaticism to bring to Washington the cherry trees she had so admired during her travels in Japan with her diplomat brother.

After 24 years of fruitless entreaties, Scidmore’s fantasies finally found fertile ground with the First Lady, who had a mind to beautify the new West Potomac Park. The city of Tokyo arranged to donate a large number of ornamental Sakura, but the trees arrived infested with insects and nematodes, and agricultural inspectors ordered them destroyed by fire. Two years later, another 3,020 trees were shipped, again by sea and rail—this time in insulated containers—and Taft and Chinda planted the first of these saplings.

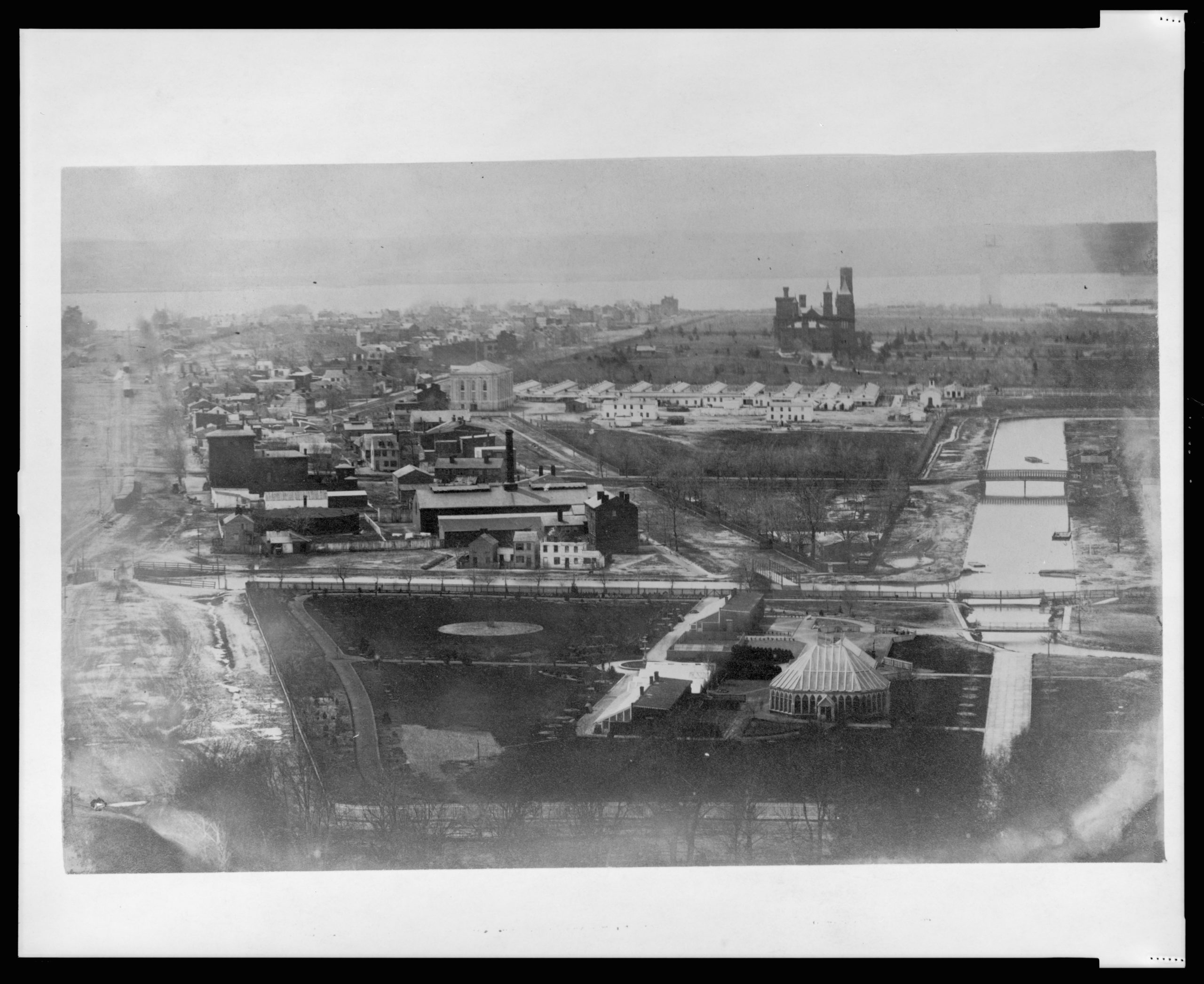

During the Civil War, Union soldiers camped and grazed cattle on the Mall, 1865, photographic print on card mount : albumen [courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington, DC]

We return the following day to the National Mall, bordered now by a long line of food, ice cream, and souvenir trucks and their idling engines’ stench of hot carbon (not altogether unpleasant). Many are decommissioned mail trucks, the eagle-envelope logo thinly painted over in white. The marble and sandstone of the surrounding buildings and memorials blush rose-gold as the sun sets.

The original plans for Washington, DC, were drafted in 1791 by Peter L’Enfant, a member of George Washington’s staff during the Revolutionary War and a sometime portraitist of the general. The polestar of L’Enfant’s federal city was a grand avenue connecting the White House and the US Capitol, including a statue of George Washington astride a horse. L’Enfant made no friends in the process of his surveying, however, and after an eminent domain demolition of a prominent landowner’s partially built mansion, he was relieved of his duties. Although the city is mostly the product of the French architect’s original layout, the grand avenue and the statue were never built.

There have been several regimes of design for the land L’Enfant had intended to be “400 feet in breadth, and about a mile in length, bordered with gardens.” In the first years of the 1850s, just before his death in a steamboat explosion, the young horticulturalist Andrew Jackson Downing, drafted a plan for Victorian landscaping and architecture that would guide the Mall’s development for the next 50 years, intending a “public museum of living trees and shrubs.” The first of the Smithsonian museums was completed in this period, and the Washington Monument was erected approximately where L’Enfant’s equestrian statue would have been. In 1902, the Senate Park Commission’s McMillan Plan dictated the replacement of Downing’s greenhouses and gardens with an uncomplicated expanse of grass, monuments, memorials, museums, and reflecting pools. Today, the National Mall is the nation’s most-visited national park, 309 acres of National Park Service–administered land, with the Capitol at one end and the Lincoln Memorial at the other.

The National Mall and surroundings with Smithsonian Institution Building and unfinished Washington Monument, 1863 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

For seven weeks this fall, the artist Suzanne Firstenberg planted 660,000 small white plastic flags—the kind used to indicate a lawn recently treated with pesticides—in the fields surrounding the Washington Monument, each flag representing a life lost to the Covid-19 pandemic in the US. In contrast to the lavishly personalized panels of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, which has been displayed in the same location, these markers were mostly anonymous, though mourners were invited to leave an epitaph in Sharpie. The project, titled In America: Remember, was a temporary memorial, seemingly a contradiction of terms. The work functioned not so much as a remembrance of an ongoing crisis, but as a recognition of its scale, which overwhelms the personal to the point of dissociation.

The Mall is often called a “stage for democracy,” and one can sometimes hear the muffled sounds of pulleys and curtains from behind the scenes: Two days after the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, at which Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, the head of COINTELPRO marked King in an internal memo as “the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation.” During the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam in 1969, President Nixon privately joked that he should extinguish a candlelit vigil with helicopter rotor downwash. After the Million Man March in 1995, Louis Farrakhan’s dispute of the Park Service’s official crowd estimate inspired Congress to explicitly prohibit such estimates in the future. The George Floyd rebellion in 2020 involved the righteous desecration of several monuments and other property damage, answered by a surge of police and military reinforcements, and by the city’s establishment of Black Lives Matter Plaza, a nearby section of street painted with those words.

The cherry blossoms are blooming in New York. Back in Washington, the repercussions of conservative reaction ring through the halls of power, animated by an originalism that takes its sense of history from equestrian statues. Meanwhile, members of the ruling party draft newspaper editorials and fundraising emails, unwilling or unable to bring about the fundamental changes to our nation that were made necessary by its flawed premise. On the Mall, the National Park Service is installing compaction-resistant soils and rainwater retention cisterns to maintain a healthy lawn. Elsewhere in Washington, its agents lay siege to homeless encampments and evict those who already sleep on the street in a city the Service calls “the second home of every American.”

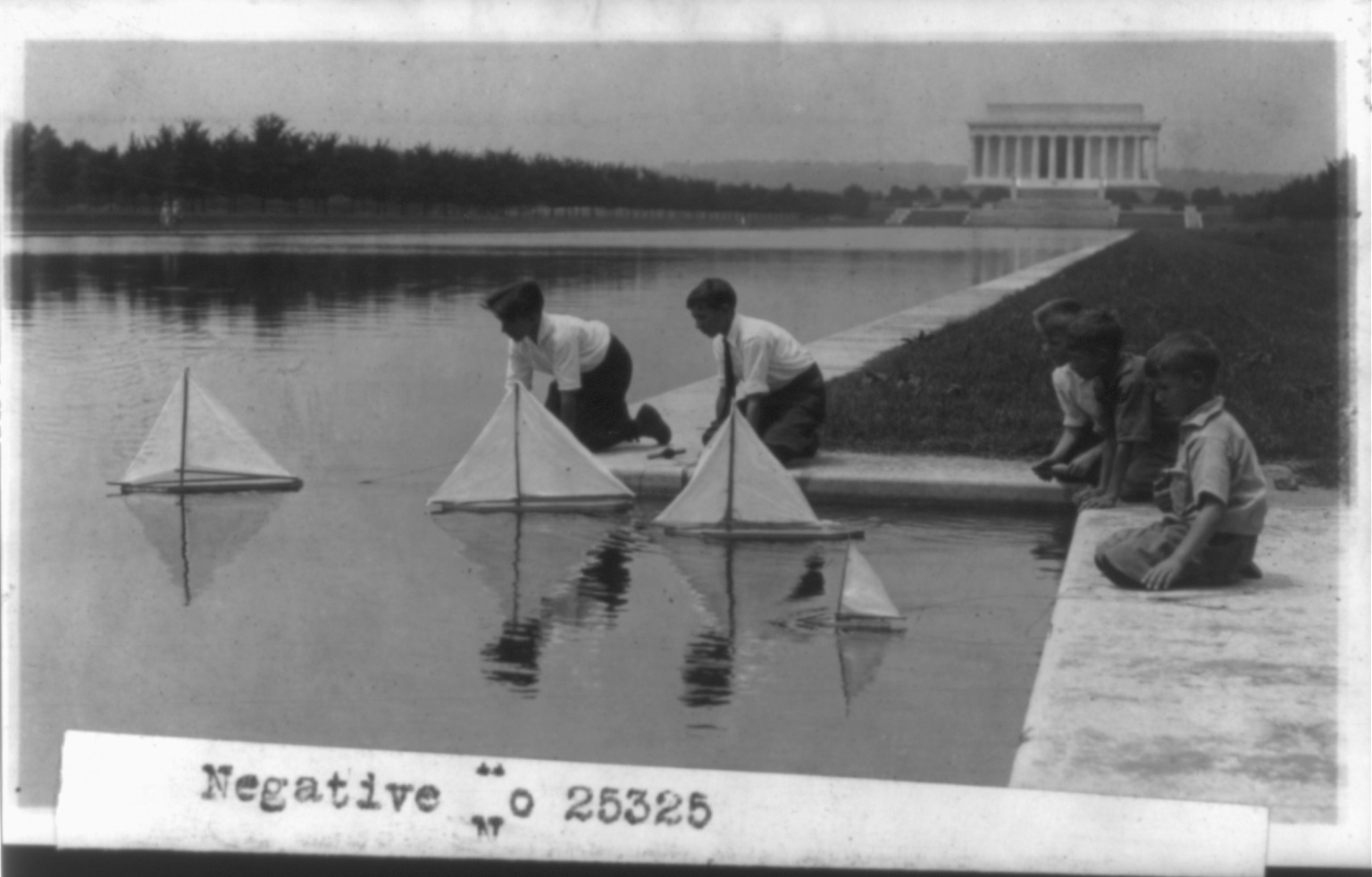

Children with sailboats at the Reflecting Pool, c.1920–1930, photographic print [courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington, DC]

Maxwell Paparella lives in New York City. He is the managing editor of Screen Slate, and his fiction and criticism have appeared in BOMB Magazine, The Brooklyn Rail, Pioneer Works’ Broadcast, and elsewhere.