Mae Ling Lokko: On Coconuts and Earthships

Share:

Mae-ling Lokko—an architectural scientist from Ghana and the Philippines, and an assistant professor at Yale University’s School of Architecture—is best known for her research and work on agro-waste and renewable biobased materials. In her artistic and design practice, she focuses upon investigating and prototyping participatory models of production. In preparation for the Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, the Ambasz Institute spoke with Lokko about upcycling and material repurposing in architecture, the future of sustainable architecture, and asked her to comment on an early upcycling experiment of the 1970s by architect Michael Reynolds. Reynolds’ first “Earthship”—located in New Mexico—was a low-energy, self-sufficient house made from aluminum-beverage-can bricks and rammed-earth automobile tires.

Eva Lavranou: Architectural scientist, artist, designer, educator, entrepreneur. Your practice brings together many disciplines. How did you get involved in natural materials and upcycling?

Mae-ling Lokko: At the time I was in boarding school in Ghana, the dormitories had no green space. For some reason, at that age, it really agitated me. So, I began this landscape design project, which became part of our weekly community service program, and therefore [everyone in school became required] to work on [it]. I think my classmates still hate me for that. What I didn’t understand was that the school was sitting on marshland. All of these plants we were importing onto the site to grow just wouldn’t survive, no matter what we did. This bothered me for years after.

So a few years after [that], I was in college as an undergrad in the States, [and] I got a grant to go back and continue the landscape project. And again, I tried everything. One of the things that our vice principal brought to the table was to use the husk byproduct, the husk of the cocoa bean, as a soil additive. I remember being fascinated at the fact that this waste, which was incredibly prevalent and abundant—and also free—could be used to improve the quality and health of the soil. This stayed with me, and while I was doing my PhD at the Center for Architecture Science and Ecology, which was this academic industrial program between Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, I decided to go back to agricultural waste, because it was the one material resource that I felt could scale. It was also in the hands of people who typically didn’t get to access value from the products they were producing.

I first discovered the work of El Anatsui, the Ghanaian sculptor, when I was an undergrad. I was blown away at the fact that his shimmering large-scale sculptures were made from bottle caps, discarded byproducts of containers that we use to drink everything from Coke to alcohol. In his work, there was such an intricate suturing, almost like a surgeon’s care in joining these bottle caps together to form these beautiful sculptures, which, to me, reinvented classical West African art textile traditions into something incredibly new. I always go back to this element of transformative care of these discarded objects. El Anatsui has been a north star for me. He has inspired a generation of West African artists, who are doing incredible things and [who are] also working with byproducts from industrial and colonial economies. El inspired my generation of creatives to become colleagues in the work that we’re doing right now around design and art with overlooked materials.

Mae-Ling Lokko, CASE Upcycling Pavilion, installation view, 2016 [photo: Sarah Reynolds; courtesy of the artists and Ghana Agrowaste Rotch Studio]

EL: You grew up between many culturally different places. England, Malaysia, Grenada, Philippines, Ghana. How do you think all these unique observations in different social, economic, and racial contexts affects your design and your teaching approach?

MLL: Looking back now, when I was a kid and moving through these very different cultures, it was difficult. None of these cultures—from Saudi Arabia to England to the Caribbean, or to Asia in general—were necessarily cultures that were easy to transition between, from the food, to the humor, to their race systems. The only person who looked like me was my brother. We didn’t even look like our parents. I think that aspect of being an outsider is something that has held true till today. There are strategies and skills we used to quickly adapt, and over time, [that] I didn’t realize I was practicing … that have become very important for me as a designer today. Being able to immediately understand the spoken language, and also the things that are not said, makes you become an insider, despite the fact [that] you look different.

My work sits between a range of disciplines, as you mentioned. Moving between arts, the sciences, engineering, very different cultures in the classroom, in the workshop, in the machine shop. I think the apprehension, in terms of entering those spaces, is something that got lowered and lowered through my childhood experiences. Also, for teaching, I imagine my students as outsiders who are entering a movie in the middle of the film—they’re joining a discourse, they’re joining a discipline that has had a long history. Being able to see that with fresh eyes, the eyes of someone who’s just walked in, is something that is really helpful, because I can put myself in their shoes, coming to these topics for the first time.

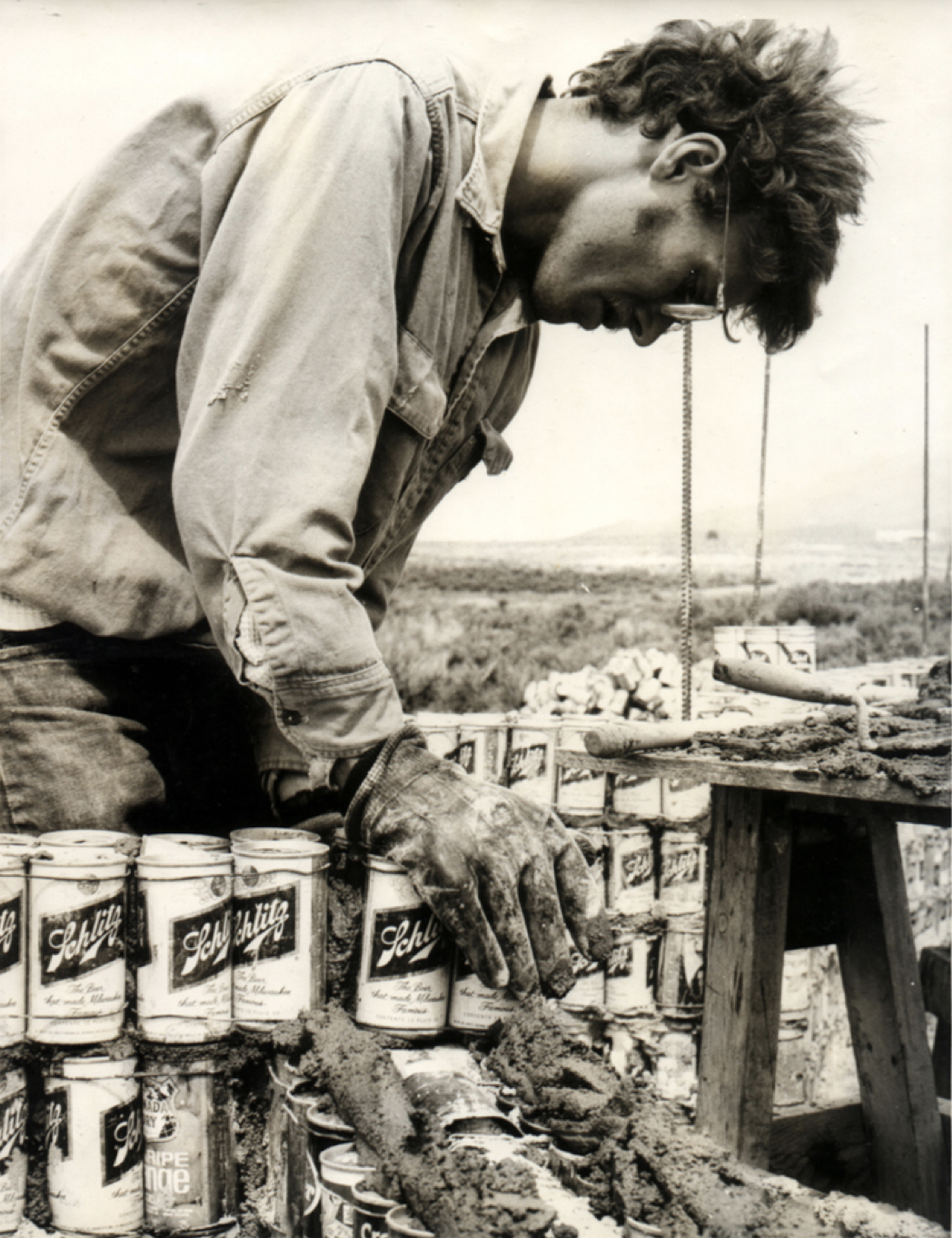

Michael Bailot laying cans to construct the first beer can house in Taos, New Mexico, 1972 [courtesy of Collection Earthship Biotecture]

EL: I would like to go back to the topic of materials reuse and discuss an early upcycling experiment in US architecture, the work of architect Michael Reynolds, in the 1970s, who produced houses made of beverage cans, the so-called Earthships. What do you think about reuse and material repurposing in architectural production today?

MLL: For me, Reynolds brought to the surface this critical issue in our modern material economy around the fact that the end of life of the material wasn’t something that was critically thought about or designed for. In his view, everything from the beer can to the rubber tire became the new natural resource. The fact that, today, the problem is the solution, that “waste is the resource,” got inoculated in a contemporary way in the 70s, during the energy crisis. Another thing that Reynolds [built upon] was that all of these material systems could interact in a very specific way, based on properties of the environment. So, the rubber tire packed with earth forms a new type of thermal mass, in place of a brick wall or a rammed earth masonry system. This became a new wall that was buried in the ground. It also had properties and energies that we needed to recognize, to see, and appreciate fully. This layer of value that Reynolds added onto reuse is something that I think we’re still grappling with today.

Today, the options that exist at the end of a material’s first life span from reuse to recycling to landfill. Of all those three, reuse is the most powerful one in terms of extending the material’s life. But what does that really mean for those of us who are designing today? How do you actually design so that an object, or whatever material, has three lifetimes in mind? We have very few tools for thinking about the long now, and I think this is where a lot of energy is focused. Recycling is very complex, because mixed materials need very difficult or energy–intensive ways to separate them. And if we do, we end up creating tons of pollution or even higher–embodied carbon materials that cannot return to our land.

EL: You do a lot of work in the material life cycle. I would like to hear more about your research. How can the materials that you experiment with return to earth?

MLL: When I started doing this research, we were working with coconut husks, which were the byproduct of this superfood and a growing cosmetic industry. [About 60 million] metric tons of coconuts are produced every year, and all their skins, their husks, are just deposited and combusted on streets or on farms, which becomes a huge source of land pollution. Initially, the goal was just to figure out how to make really high-value, beautiful building materials from these husks. But what happens to those coconut building materials that you’ve just made? And this is where designing for longer lifetimes became more intentional. And also, what new material labor economies were being thought about to enable the production of these upcycled building materials? So, I began to think about the life of a material in a very different way.

Finding a way of valuing everything in the material and directing it in flexible ways, according to where [it’s] needed—the pathway for a coconut husk isn’t necessarily just about producing a really strong fiber board that can replace plywood. Maybe there’s a need for the cocoa peat derived from the husk to become a soil substitute, because the land has been incredibly exhausted from monoculture coconut plantation farming. Or maybe it’s needed as a fibrous roof assembly, because heat gain in houses is intense in the tropics, on the roof. So, there was this spectrum of possible lives, possible careers. Lastly, thinking about how they return to our environment safely, because they’re not going to last forever: Everything we do to make them live longer, in terms of putting in glues and coatings and resins, usually ends up suffocating the material and giving us huge problems in terms of degradation.

Mae-ling Lokko, Coconut Mother Prototype, 2022 [photo: Tanner Whitney; courtesy of the artist]

So, the question of what it would really mean to design a material for soil health emerged. In some ways, I’ve started working backwards, looking at these long-standing indigenous practices of farming that were able to nurture the soil over long periods of time. Those farming practices were incredibly biodiverse. No crop was the emperor. They always had collaborators and friends around them. They also engaged with other kingdoms of life, like fungi, that were very good chemists at re-engineering and breaking down these materials. The human labor systems around these forms of farming were very sophisticated. How do we support that and scale up those ways of growing and processing materials?

In many ways, your building material, or whatever your design, is going to look so different once you take into account that vision of producing. So, if, in the rainy season, certain types of crops grow, I know that I might produce an acoustic panel made from a diverse byproduct inventory based on what’s abundant at that time and place, and it’s going to perform fantastically in that place because it was nurtured in those climatic and geological conditions. That way of working backwards has been a productive roadmap, rather than starting from everything everywhere all at once—infinite possibilities.

We have to look back at our historical systems and societies that had a lot of intelligence and wisdom [about] how to grow and transform materials. It brought a lot of actors who haven’t necessarily been in the design space, at the table, whether that’s a farmer, or a trader of agricultural goods, or the waste collector. Because, most of the time, a lot of these people are never talking to one another and may not realize how one decision they make impacts someone down the line. The sooner and more urgently we can have these conversations, the more chances we have at accelerating a shift in our built future.

EL: It’s very inspiring that you’re trying to bring all these people together. It’s not only about healthy materials, but the entire complex system behind the materials. I would like to go back to the Earthships for a moment to talk about this. Reynolds started also exploring passive energy systems, water harvesting, and food production. How can architecture investigate all these connections between consumption, waste, and production to restore the environment toward a more regenerative future?

MLL: What’s so powerful about the Earthship is that there’s a certain relatable scale. It’s the scale of the home, at which a homeowner could build with a certain group of people around him. At that scale, he was able to define these really core and legible principles around sustainable living.

The first aspect that I find compelling in the Earthships, because it recalls principles from vernacular architectures around the world, is that they are not sitting on top of the land but are burrowed into the ground. New Mexico, where a majority of these Earthships are built, is a desert climate where you have these huge fluctuations between day and night. The ground is the most slow–moving material in environments. Its temperatures don’t change as quickly as the extroverted air that’s hovering above it. The house being buried in there, particularly at a specific level, keeps the temperatures of these materials quite stable. This relationship to land, as a passive approach, is the foundation. Whether he’s using the rubber tires or adobe earth masonry doesn’t matter, really. The fact that there’s a thermal mass being made of something to retain those qualities of the earth, or in conversation with the earth, is the foundation.

Michael Reynolds, Exterior view of Beer can house, Taos, New Mexico, 1972 [photo: David Hiser; courtesy of United States National Archives and Records Administration.]

Movement of water around the Earthship is also [among] the most fascinating things. There’s a beautiful section from “Earthship space,” a thesis on Reynolds’ work, which personifies water in the Earthship. In this work, you are asked to imagine that you were a droplet of rain or water moving through the building, and then it hits the roof surface. It basically gets accumulated in certain systems, cistern systems. It moves through plant modules, where it’s filtered and cleaned. “Clean” in these systems just means that all these components dissolve in water, which may not necessarily be useful to us as humans, [but those components] are being used by plants. And you get water for washing in your kitchen, in your bathroom, which introduces new types of materials in there, from urea to anything coming out of your food, your plate, or whatever. And those are nutrients that go into the external plant system. The gray water goes into the exterior landscaping system.

This journey of any material, especially water, because it’s fluid, is so important in changing the way we see and build infrastructure. We see all these things as static, and we hide them away. We don’t think about their quality—or their quality of life—while they live in our building. Particularly, the water cycle in the later generations of the Earthship houses, where they introduce the food growing, comes full circle when you can actually grow plants. Reynolds writes about this potted plant, which was fed from his kitchen drain, and which grew to be a very strong tree. It’s robust, it’s super healthy—like, an eight-inch-thick diameter over the years. And that’s a one-to-one relationship—where the human and this plant that’s growing up from one’s kitchen sink—that is so relatable and visceral.

Mae-Ling Lokko, Healing Meadow, 2022 [photo: Selma Gurbuz; courtesy of the artist and Z33 Gallery, Belgium]

You see the growth of another organism, another being in your domestic environment. This is one of the most powerful things, because it translates this cold, abstract, technological view of controlling matter and materials to something that’s cultural. It’s changing your domestic rituals in relation to life within your house.

There’s a really beautiful passage from an interview in a research thesis I found. [It’s] with one of the inhabitants of an Earthship home. I’m just going to read it, because I think it summarizes how the rhythms of the Earthship foster a connection of humans with the outdoor world.

When it rains for days on end, we become conscious about conserving power and appreciate the simple joy of reading, playing Monopoly, or doing a puzzle under a single light with my mate in the evening. While we rejoice in the bounty of rain, which will provide our water, we simply switch over to less power–consuming activities because the sun’s gone. But when the sun shines again, we reverse our behavior. We use power to run the washing machine, which uses restored water resources. When we enter a long period of drought, water conservation takes priority.

Our thought processes change from the plants needing watering (go and fill the watering can from the sink), to the plants needing watering (go and wash the dishes, or do a load, and make them some gray water). And so, the sort of relationship one has to a plant, to the climate right outside, and the things that one’s doing in the domestic space is reconnected, which I think is different to the way we live today, where it is the flipping of a switch or the pressing of a button that controls the climate inside. We don’t necessarily think so much about all of these forces of nature and other kingdoms of life that are living with us. This power of reconnection is key in the ecosystem of the Earthship.

EL: It’s fascinating to realize how much intelligence there is, throughout history, in Indigenous cultures connected to the earth. As you speak, I’m picturing a living architecture, instead of a static one, where humans, plants, the building, the food, are all connected in one system. You mentioned scale as an important factor to control the Earthships. I’m wondering how we can incorporate all this land knowledge into today’s complex system.

MLL: This question gets to the heart of what I think is probably the weak point in the Earthship concept. There’s a lot to admire about it, but the one thing I always hark back to is the autonomous self-sufficiency paradigm in which it operates. One goes off, into the desert or some kind of depopulated area, and constructs an environment that doesn’t need anything else or anyone else. I think there is, obviously, the material intelligence, the connection with resources—being resourceful—that is powerful. But looking at the population around the world today, the kind of housing we need to provide, and the density that our species has in cities today, the Earthship is not a plausible model for us to scale.

Mae-Ling Lokko, Grounds for Return, installation view, 2022 [photo: Selma Gurbuz; courtesy of the artist and Z33 Gallery, Belgium]

This issue of connectedness and ecosystem thinking is something about the Earthship methodology, or Earthship paradigm, that I think needs to be looked at further I think a lot about the types of people who are attracted to Earthship homes, and they may range from environmentalists all the way to groups that want to be isolated and to control their borders and resources, so that no one else can enter or take away what they have. This question of autonomy is at the heart of it. For me, one of the biggest challenges—and we’re still grappling with this today—is how do we provide energy, food, water, shelter for a society that is incredibly divided in terms of equity, diversity, and inclusion?

One of the most inspiring examples I’ve come across recently, in terms of an ecosystem approach to scaling access to electricity, is in central Africa, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where [about] 20% of people today have less access to electricity. They envision a metro-scale energy infrastructure where wealthier stakeholders—for example, industry or larger commercial enterprises who can afford higher rates for energy—are always living in contact with labor economies or domestic settings where the majority of people cannot afford electricity at that price. Furthermore, where such systems exist next to each other, there’s an opportunity to invest in and design an energy infrastructure that maximizes renewable sources of wind and sun, [as does] the Earthship, but also has a reliable energy source—geothermal or fossil-fuel based.

There’s always a priority to reduce in the Earthship—whatever you’re taking from a nonrenewable resource, and instead using, first, those renewable sources like the sun and wind, which may vary. So, that vertical energy infrastructure that is democratically distributed to meet the reality of different levels of affordability in our society. It’s one that I find, at least, captures the complexity of our world today, rather than going off into isolation, into this self-sufficient mode, which, for a period in time, can provide us comfort and security, but ultimately will catch up with us.

In a recent podcast interview with Reynolds, I realized he was very aware of this problem, and he actually responded to this question of autonomy, after a client group came to him and wanted to grow plants in their Earthship, and also have an underground chamber for guns to prevent anyone [from coming to] steal from them. In response to this, he says the ultimate form of security is not walling ourselves off and preventing anyone from getting what we have. The ultimate form of security is to make everyone around you sufficient. Ultimately, that aspiration of Reynolds’ is something I share, and that I think requires an ecosystemic sort of thinking, as opposed to this atomized paradigm that we’ve seen in the completely “autonomous” idea of the Earthship.

EL: Well, making everyone sufficient through interconnection—so based on that, what do you think should be the focus of architecture for the future?

MLL: I think architects and designers have occupied a very specific place in this ecosystem: somewhere between the owners of these production enterprises—the people who accumulate value, much more value than everyone else does; those are the people who can afford an architect—and the consumers. And that’s a static business model that hasn’t evolved much for a long time. It’s my hope that If architects will be able to position themselves in other parts of this framework, especially in the underbelly—where one is working with a new inventory of materials and emerging 21st-century community enterprises or corporations that are trying to do the right thing, especially farmers or producer communities who may have traditionally been alienated within this value framework. I think that opens up an expansive role for what new material futures, or the role of the architect, can be.

From an education standpoint, [all] this requires rethinking what goes into architectural education. We’ve been entrenched in learning, particularly from a technological standpoint around the physics of a building. Very little attention has been paid to chemistry and biology, and those are the fundamentals of seeing our buildings as living organisms. That [education] also helps us become able to reconstitute the DNA of how we design materials. So, I’d love to see those types of interdisciplinary convergence opportunities.

From a cultural standpoint, I think a lot of the work we have to do is within. The biggest barrier that I see to using a coconut panel today, in places where you have tons of coconut husks—like Ghana and the Philippines—is not that the technology doesn’t exist, but people don’t desire it, because these materials are attached to an image of development that is perceived as “regressive.” Everybody wants concrete, glass, and steel. Those are the “materials of the future.” They communicate wealth. And that’s something that we’ve inherited from centuries of colonialism and [are now living with] in a post-industrial era.

Mae-Ling Lokko and Hayley Eber with Cooper Union School of Architecture, Everything’s On The Table, installation view, 2022 [photo: Evert Palmets; courtesy of the artists and the Tallinn Architecture Biennial]

And so, how do we shift our cultural affiliations with materials—that have a lot to do with being comfortable, with being who we are, where we’re from, connecting with what’s around us, figuring out what our own identities are, rather than this sort of globalized consumer identity that we’ve bought into. This shift cuts across every facet of our lives, our food, our clothes. So, it’s a universal problem, but until that mindset shifts, we may not see the kind of demand that is needed to normalize these ways of living, and these ways of working, with our material resources. These cultural forces are going to be some of the most important ones in inoculating a different architecture.

EL: Where do you currently spend your energy?

MLL: As a Ghanaian-Filipino, young female architect operating between Africa and here, in the United States, I think my most important project right now is a book—trying to distill how we might return value to these generation mechanisms, which is our land, and our labor. And this is where I’m hoping to spend a lot of my time over the next year. I think the thinking, the doing, the making, the teaching are all feeding off each other, almost like an ecosystem. But yeah, it’s kind of schizophrenic.

This exchange has been edited for publication.

Eva Lavranou works at the Ambasz Institute at The Museum of Modern Art, assisting in exhibition and publication planning and in environmental design research. She holds a Masters in Design Studies: Art, Design and the Public Domain at Harvard Graduate School of Design (2022) with Distinction. She has previously studied architecture at the University of Thessaly (2018) and at the Politecnico di Milano (2014–2015). While at Harvard she worked as curatorial assistant for the Department of Exhibitions and as curator at the GSD Kirkland Gallery. In 2021 she participated in the Venice Biennale. Her work focuses upon design research, curation, activism, and public space interventions that promote social change.