New Territories of Queer Separatism

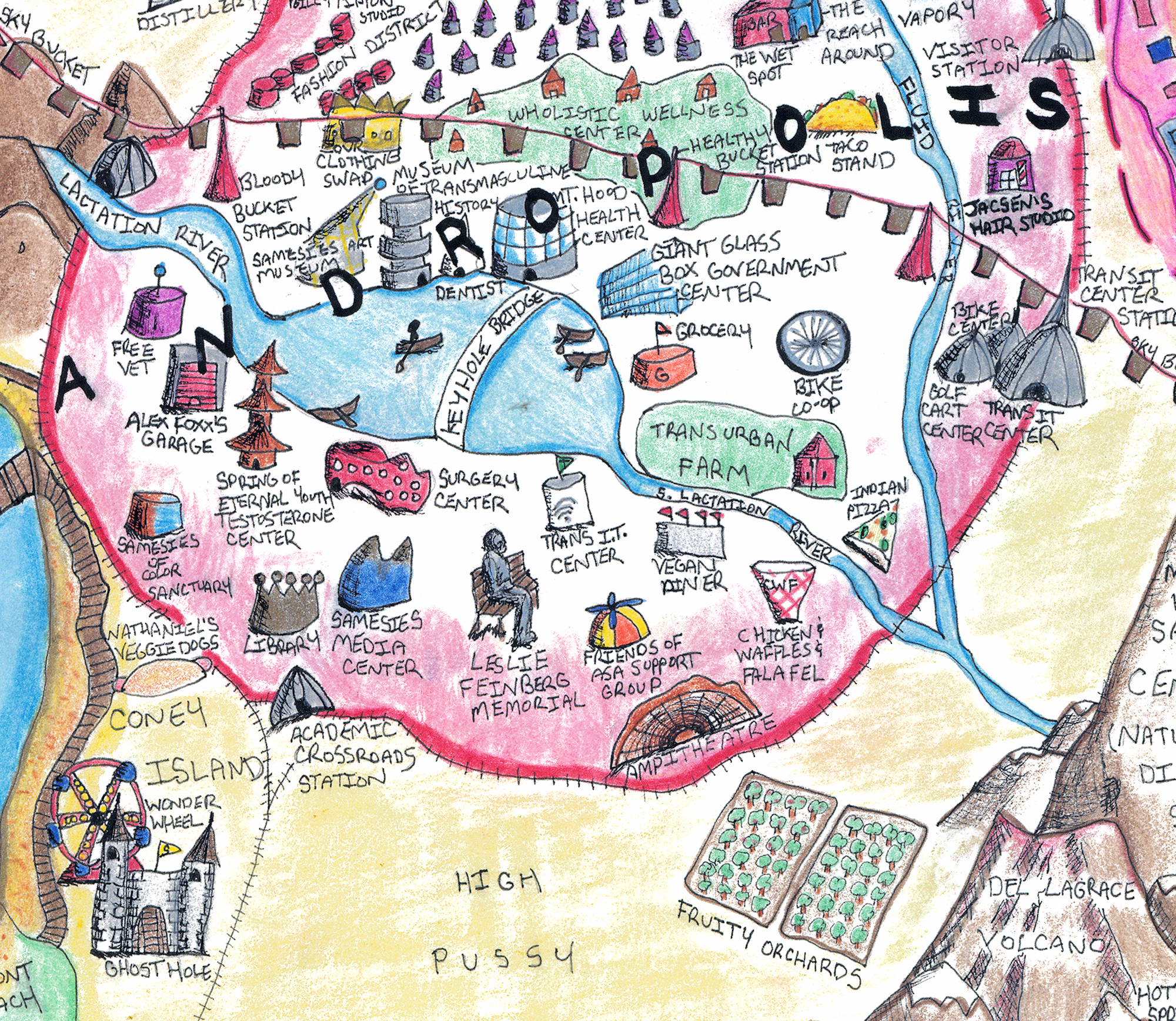

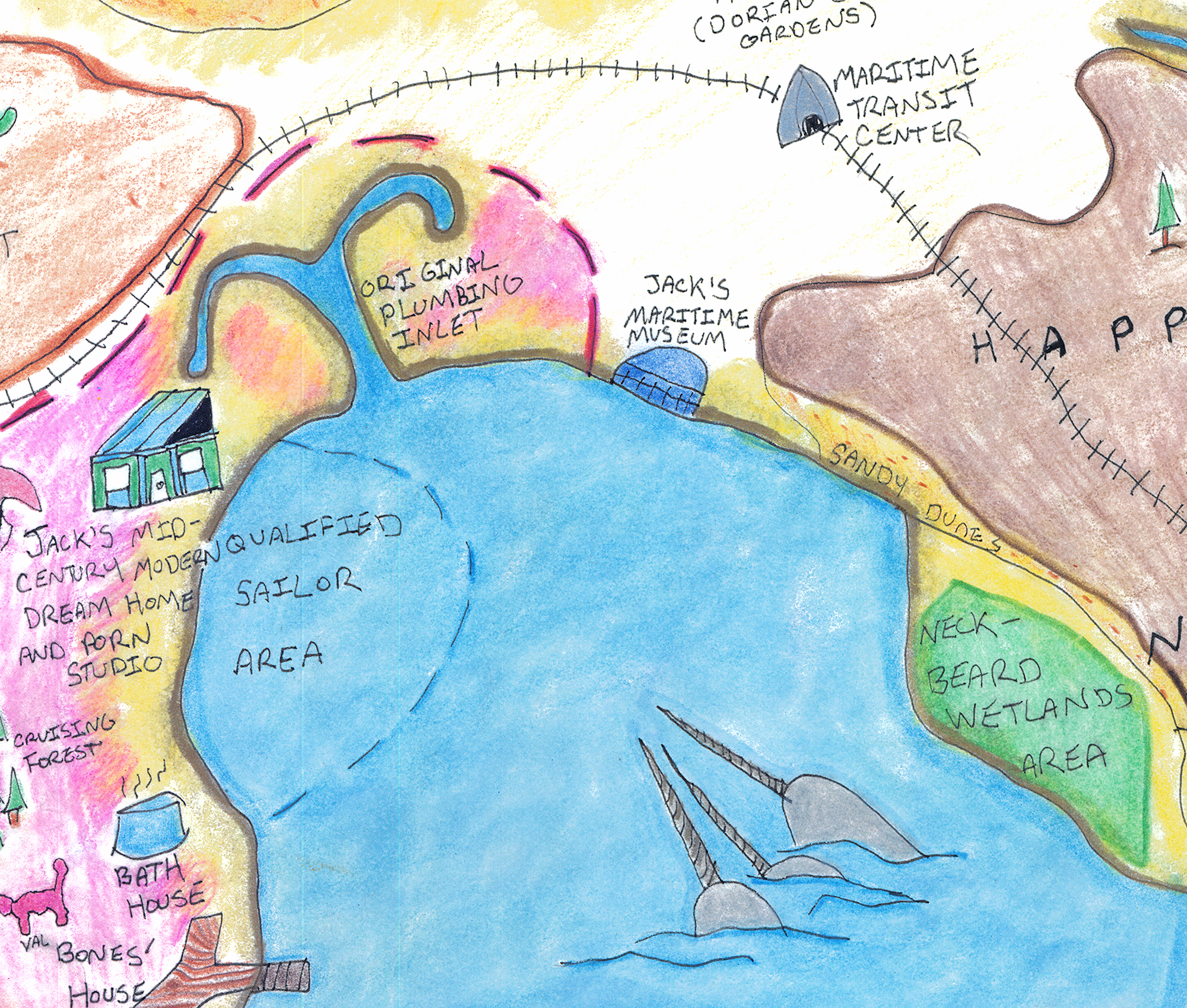

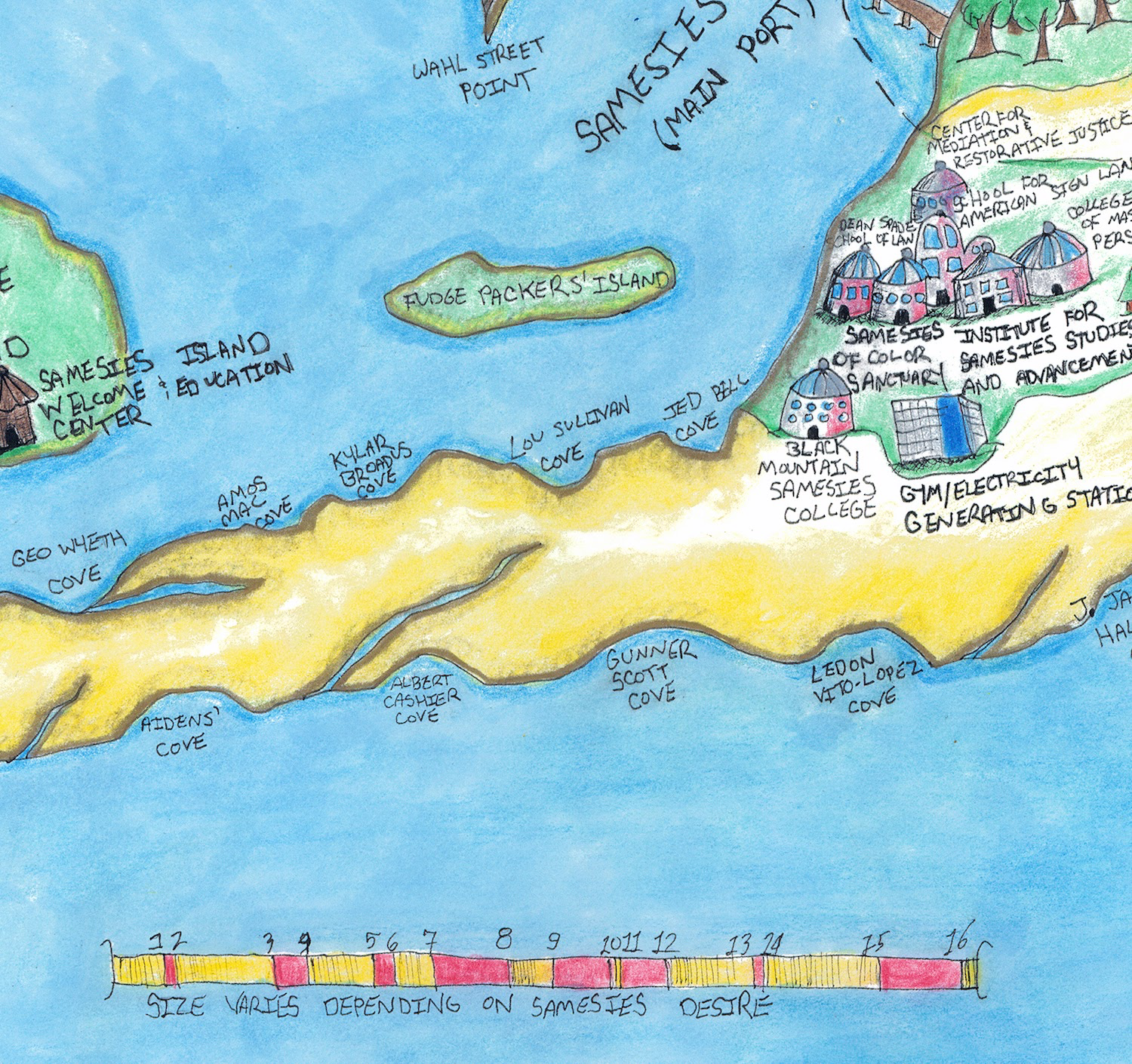

Jaimes Mayhew, “Samesies Island”, 2014 [courtesy of the artist]

Decades after first wave radical lesbians and feminists sought empowerment in autonomous, womyn-only communities across rural America, contemporary artists return to queer separatism with questions of legacy, documentation, and sustainability, commerce and digital media. In doing so, they reveal archival treasures in historically revolutionary social islands.

Share:

In February 1969, Lee Lozano began her conceptual General Strike Piece. Taking physical form as a statement typed on a piece of paper, the work was activated when, in her daily life, Lozano adhered to own her directive to “GRADUALLY BUT DETERMINEDLY AVOID BEING PRESENT AT OFFICIAL OR PUBLIC UPTOWN FUNCTIONS OR GATHERINGS RELATED TO THE ART WORLD IN ORDER TO PURSUE INVESTIGATIONS OF TOTAL PERSONAL PUBLIC REVOLUTION,” and to “EXHIBIT IN PUBLIC ONLY PIECES WHICH FURTHER SHARING OF IDEAS & INFORMATION RELATED TO TOTAL PERSONAL [sic] & PUBLIC REVOLUTION.”

Lozano extended her disengagement from the art world toward another social group entirely with Decide to Boycott Women (1971), a piece which dictated that she refrain from relationships and interactions with women for what would be the remaining 28 years of her life.

Around the same time as Lozano’s conceptualization of nonparticipation, radical feminist-lesbian separatist communes began to appear across the United States. This separatist impulse was one response to feminist and gay liberation movements, which some viewed as unable to account for the specific concerns of lesbians. These activists in turn sought to divorce themselves not only from the normative ideals of patriarchal and capitalist society, but ostensibly from those of liberation groups whose feminism was still simply too straight, leading to what Nancy Groschwitz called, in a late 1970s treatise titled “Practical Economics for a Women’s Community,” a “schizophrenic existence” between the straight world and radical political goals. Deeming society at large irredeemable and taking a stance against superficial educational and reformist measures, this early generation of separatists saw wholesale withdrawal as the only option to build an inhabitable social space.

The logic of refusal rejects any system that in turn denies participation and personhood to individuals based on gender, sexuality, race, religion, age, or ability; the aesthetics of refusal meanwhile tend to be invisible. Lozano’s “life-as-art” works took the form of intangible, and by definition private actions. In parallel, on the opposite pole of lesbian separatism, 40 years after the first wave there remain few accounts of the exoduses and values of the many communities that once dotted the American landscape. To adapt the famous “if a tree falls in the forest” adage: if an artist’s practice takes place out of view—or, if a lesbian separatist community flourishes in rural Arkansas—did it really happen?

In the 21st century, contemporary artists and art collaboratives have returned to the archives and practices of separatism as a strategic tool for (dis)engagement; those profiled below call upon its specifically lesbian heritage, and bring this legacy, its history, and its historiography into focus.

Jaimes Mayhew, “Samesies Island”, 2014 [courtesy of the artist]

As the public art collaborative Dyke Action Machine!, Carrie Moyer and Sue Schaffner turned to womyn’s lands in the early 2000s with Gynadome (2001), demonstrating both a skepticism towards separatism, and its simultaneous impact on their work. More recently, artist Rachael Shannon’s pop-up spaces, such as Breastival Vestibule (2013 – ongoing), have sought to provide environments in which individuals can navigate their senses of self in relationship to different scales of community. Ginger Brooks Takahashi has ex-patriated herself from New York and started a general store with artist and collaborator Dana Bishop-Root in North Braddock, PA, operating outside traditional capitalist structures. For the Samesies of Baltimore, separatism provides the platform for a speculative island fantasy in which members of the group can exercise agency. Yet for Leah DeVun, an artist and historian interested in notions of queer genealogy and intergenerationality, separatism remains a misunderstood part of the queer archive.

Dyke Action Machine! (DAM!) originated as an affiliate of Queer Nation, a direct action group aimed at ending discrimination toward all LGBT people. Yet their sentiment was that Queer Nation’s leadership and initiatives had begun to prioritize masculine identities under the queer umbrella—it was the early 1990s, and activism was increasingly directed toward AIDS awareness—and founding members of DAM! swiftly left Queer Nation to form a separate entity devoted to lesbian visibility. Consisting of various artists and activists in its early years, DAM! eventually pared down to a core duo: painter Carrie Moyer and photographer Sue Schaffner, who worked collaboratively under the name from 1991 to 2008. Both having backgrounds in advertising, the pair blitzed New York streets and public spaces with wheat-pasted poster series such as Do You Love the Dyke in Your Life? (1993), which subverted Calvin Klein’s infamous Mark Wahlberg underwear campaign by recasting it with what they describe as “identifiable lesbians,” in an already homoerotic framework that fetishized the muscle-bound male form. In a cultural context of heteronormative rhetoric about the integration of gay culture into mainstream society—via marriage, the military, and other institutions—DAM! insisted upon the importance of a separate subcultural space. Campaigns such as Gay Marriage: You Might As Well B Straight (1997) and Lesbian Americans: Don’t Sell Out (1998) urged gay consumers to resist targeting by savvy marketers and liberal rhetoric. As gay codes were being cracked from commercial culture to queer theory, DAM! reinscribed encryption, sending direct messages to lesbian audiences.

When DAM! applied their “culture-jamming” and coding methods to the Internet with Gynadome, separatism went from being the subtle strategy behind their work to being its subject. Engaging nostalgia for the womyn’s lands of the 20th century alongside survivalist anxieties about technological progress, DAM! created an ellipse for a projective utopian, science-fictional fantasia. In the project’s narrative, lesbians return from a remote Biosphere—to which they were banished for study by “the Man” to discover they are the sole survivors of a techno-apocalyptic meltdown. The result was Gynadome, a lesbian-only planet accessible through gynadome.com, where live videos “from the future” and a “gyna-chat” function to connect lesbians virtually under the mantra, “Where women are Women, the men have been put out to pasture, and computers are just Big Paperweights.” As a cyberfeminist artwork, Gynadome expresses skepticism about the utopianisms of both womyn’s lands and technological revolution, drawing parallels between the promised and potential impacts of seclusion on the experience of individuality and community – in virtual and physical spaces alike.

Although mostly inactive, the Gynadome website still has its own clock displaying “gynadome time”—DAM!’s parody, perhaps, of the romanticized, often dated view through which womyn’s lands are perceived as frozen in utopian time. Yet some original communities still exist, inhabited by an older population of lesbians who have lived on the land for 40-plus years. In 2010, for a project called Our Hands On Each Other, Leah DeVun traveled across the southern United States to record these womyn’s oral histories while focusing on their architectural infrastructures. Built using makeshift materials with low investment and upkeep costs, womyn’s land architecture is pertinent to ongoing conversations about gentrification, development, sustainability, collectivity, and land trusts.

DeVun had friends and collaborators re-perform scenes from the archival records of the lands as documented by the independent womyn’s magazines that supported these movements and networks from the start. Engaging with history in an embodied, experiential way—rather than recording it, using text and image—DeVun’s approach seeks not only to preserve history, but also to energize it through active participation. This gesture is especially poignant as the women who founded these spaces reach their 70s or 80s, leaving few possibilities for a next generation of lesbians willing to keep their legacy going. By looking to past iterations of women’s spaces, we might understand what they currently are, and what they could be.

An artist whose practice is heavily engaged with historical subjects, objects, and archives, DeVun situates Our Hands On Each Other in the physical spaces of feminism, as well as in the constructed space of history and memory-making. She also investigates the emotional and conceptual spaces created in the discrepancy between nostalgic, festishistic, or overly romanticized approaches to the past, and the critical dismissal of separatist endeavors as “failures” that never met their radical promises or contributed to contemporary discourse—criticisms bolstered by the shifting definition of “woman,” and the matter of the population sustainability necessary to give the movement longevity. In a moment that calls itself “queer,” what can we learn from previous generations of feminists, lesbians and separatists? The answers range from practical skills needed to survive—say, how to chop down a tree—to broader notions of sustained life, such as lineage and intergenerational transmission of knowledge and culture.

Jaimes Mayhew, “Samesies Island”, 2014 [courtesy of the artist]

Of course, coming together in specialized groups is a traditional mode of sharing and disseminating new ideas, and it is with this purpose that tens of thousands of cultural travelers flock to Austin, TX, for the annual South by Southwest (SXSW) music and technology festival. For the past nine years, Austin’s queer community has found its own satellite in GayBiGayGay, a one-day event co-founded by Silky Shoemaker and Hazey Fairless that has taken place in backyards and empty lots on the east side of town. Differing from separatist festivals such as the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival—aimed at womyn-born-womyn, and held every summer—GayBi is first and foremost for queer people, though not exclusively: occurring in a highly visible and porous social space, the event extends its queer world-making to everyone. Such festivals seem to offer a revision to Michel Foucault’s “heterotopia”: a space of confined otherness—a prison, for example—that operates under rules that differ from those of larger society. Because their populations are self-selected, the temporary autonomous zones of the Michigan Womyn’s and GayBi festivals might conversely be called “homotopias”—spaces of radically open and flexible unity. But a space is utopic only to those whose vision is reflected in its physical manifestation. Recent controversies about what constitutes womanhood and who can make claim to the space at Michigan Womyn’s Festival have led some to question the line between separatism and segregation, and the costs and benefits of enforcing systems of enclosure to keep a separatist world intact.

However exclusive or specialized, festivals such as GayBi and Michigan Womyn’s by definition require the involvement of many. Baltimore-based, native Texan artist Rachael Shannon has contributed to both events, which have become integral to her artistic practice and its relationship to community organizing. Shannon created Breastival Vestibule in response to the liberation the artist felt, thanks to attendees’ ability to be topless in these spaces, an experience she sought to remake in the context of the integrated world. The result is a temporary inflatable structure conceived to promote viewers’ exploration of toplessness, and designed to travel to various kinds of public spaces, including conferences, festivals, and simple outdoor plazas. For Shannon, toplessness is an entry point to a discussion about how bodies are regulated and the expectations they’re required to meet. A video playing on a monitor inside Vestibule displays questions to prompt conversation among participants there. Structurally, Breastival Vestibule is a bubble, much like what it seeks to create: a temporary autonomous zone that mitigates the transition between public discourse and private exploration—and, at best, suggests a connection between the sheltered curves of the body and the spheres of community in the larger world.

Examples of the public and political significance of the human body and its contents certainly abound. In 1985, for instance, at the beginning of the AIDS crisis, the townspeople of Gayside, Newfoundland, voted to change the town’s name to Baytona. The artist-members of a collaboration called the Third Leg—Ginger Brooks Takahashi, Onya Hogan-Finley, and Logan McDonald—took the gesture as one of pure homophobic fear in the shadow of a then unknown disease. In response, 20 years down the line, the Third Leg reclaimed Gayside by mythologizing it. Combining various aspects of gay subculture and subverted gay cultural stereotypes into an installation and mapping project, the group created an empowered parody. Their disarming and humorous reimagining of the town with Welcome to Gayside (2006), exhibited in 2007 at Eastern Edge Gallery in St. Johns, Newfoundland, created a space of celebration, with a topography including “Bareback Mountains” and fist- and phallus-shaped islands that fit snuggly into coves. Brooks Takahashi, in collaboration with Dana Bishop-Root, contributed a graphic of the island of lesbos with icons depicting different sites and tourist activities (2009) to Herstory Inventory (2009), a drawing project initiated by Ulrike Müller; referencing Sappho’s home island, the map translated the shape of the land mass into that of a woman’s backside, with tide paths forming legs. Peppered with translations of ancient Greek poetry, as well as passages from Monique Wiitig and Sande Zeig’s Lesbian Peoples: Material for a Dictionary—which appeared, like Baytona, in 1985—this Lesbos conceptualizes community as a tribe, a designator that relates more forcefully to ideas of familial kinship and the back-to-the-land movement.

Jaimes Mayhew, “Samesies Island,” 2014 [courtesy of the artist]

The separatist topographies imagined and conveyed in these maps connect the mythic to the mundane—a crossover that occurs, albeit in more material terms, with Bishop-Root and Brooks Takahashi’s General Sister’s, a store in North Braddock, PA, for which the artists plucked what they saw to be the best ideas from independent, intentional communities. The artists applied these ideas as practical, rather than utopian, alternatives to capitalism. When Brooks Takahashi decided to leave New York three years ago, it was in part because she realized she was operating within a specific ideological position that supported an ultimately elite art scene that fosters sameness. Leaving that particular separatist bubble, she moved to North Braddock, just north of Pittsburgh, to conversely reintegrate into a larger, more democratic society, connecting to people through difference. With General Sister’s, Brooks Takahashi and Bishop-Root create a space of exchange to address the myth of the food desert in rust belt communities, trouble notions of abundance and scarcity, and change the relationship of the consumer to the store. General Sister’s will grow and sell food ingredients when it opens in the spring of 2015.

Samesies Island is another speculative island fantasy, a utopia co-produced in the collective imaginary of a group of transmasculine artists and friends living in Baltimore. According to the group, a “Samesie” is a transmasculine-identified person, assigned a gender or sex other than male at birth, who also dates transmasculine people. Samesies Island creates a space to renegotiate interactions and events in daily life that are particular—and at times, particularly difficult—to the transmasculine experience. Existing in the cognitive-emotional space of a group, Samesies Island thus allows the possibility of imagining oneself and one’s community in a space of agency and power, as a dominant rather than marginal group. Drawing upon aspects of such practices as BDSM, LARP (live action role play), and EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) therapy, group activities on Samesies Island seek to drive traumatic scenarios to healing outcomes, and to turn oppressive environments into safe safe spaces where one isn’t marginalized, pathologized, or harassed.

A year’s worth of conversations among “surveyors” Bones, Mickey Dehn, Jack Pinder, and Asa Kieswetter, and “cartographer” Jaimes Mayhew, has produced in-depth and elaborate maps for the project. The Samesies may have no desire to actualize their island in a physical sense; its primary function is as a tool to think through social infrastructure. Without the constraints of time, space, or money, the island can roam the world at its inhabitants’ collective whim. When I spoke to Mayhew, in December 2014, Samsies Island was positioned at the equator, but its location shifts as the weather changes. The island generates all its electricity through bicycles and is the ostensible home to many ecosystems: deserts, mountains, lakes, volcanoes, etc. Samesies Island has a museum (of Transmasculine History), a university (the Institute for Samesies Studies and Advancement), and a rehab center, among plenty of other amenities. Within this conceptual field of play, the Samesies assume fictional roles in the community: there is a mayor, a role co-inhabited by Bones and Dehn; Pinder is Samesies’ historian and undersecretary of cis relations (“cis” being a descriptor for people whose experience of gender matches the sex assigned at birth). As visa/immigration officer, Kieswetter conducts a thorough vetting process of all who seek admittance to the Island. Samesie status does not guarantee entrance; new recruits must also adhere to the community’s ethos, and once admitted must attend therapy sessions and support groups to heal from the traumas of interacting with the heteronormative world.

Materially, Samesies Island exists only as a map of an S-shaped island resembling a pregnant seahorse (a spirit animal of the Samesies because it is the male seahorse that, famously, carries eggs), a set of flags, each created by an individual resident as that resident’s own version of the island’s banner; and a series of videos in the style of corporate hotel promotions that serve to acclimate visitors and residents. The island motto? “Why should all of the other separatists movements have all the fun?”

This feature originally appeared in ART PAPERS March/April 2015.

Risa Puleo is a curator based in Chicago.