Nate Lewis: Latent Tapestries

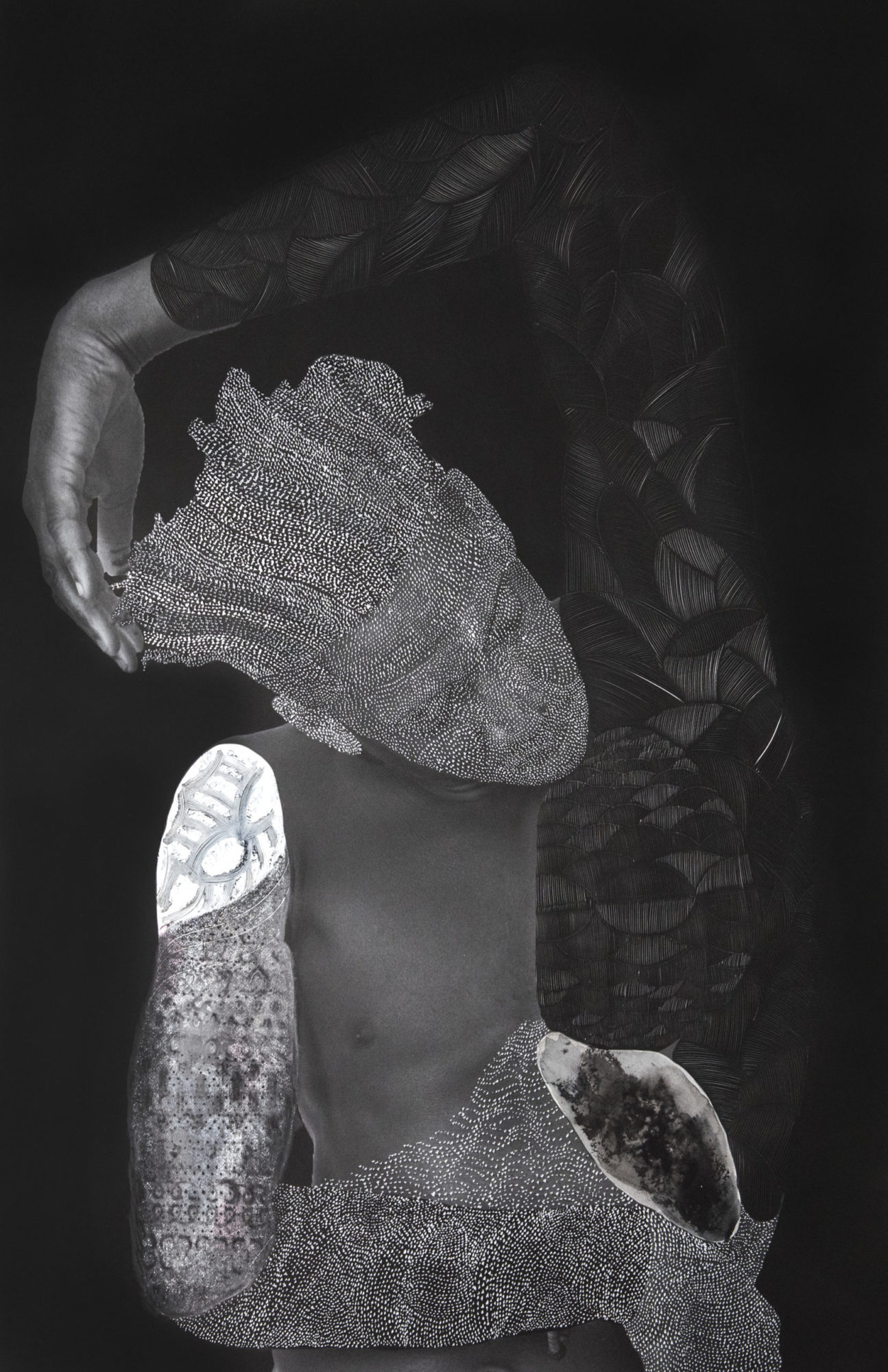

Nate Lewis, “Probing the Land 5,” 2020, hand sculpted inkjet print, ink, frottage, graphite, 44 x 60 inches [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

Nurses, often noted for their disciplined and nurturing characters, act within a pattern of care as they treat patients in highly vulnerable states. Each is held accountable for a multitude of lives. One can sense this same level of consideration and care in each cut and etching made by Nate Lewis in his works on paper. A former intensive care unit nurse, Lewis approaches each of his artworks through a diagnostic lens. Lewis considers his prints as if they are the skin, revealing a deeper complexity with every rhythmic incision he applies.

Our conversation took place in early winter at his studio in the Bronx, where Lewis was deep in preparation for participation in Untitled, ART Miami Beach and for his solo exhibition, Latent Tapestries at Fridman Gallery [March 1–April 5, 2020].

Tash Nikol: I saw your body of work Signals on view at Paris Photo with Fridman Gallery, which is where your upcoming show Latent Tapestries will be on view. How did you become connected with them?

Nate Lewis: I met lliya Fridman during my time with Pioneer Works, and then he came to SPRING/ BREAK, where I showed at the end of my residency. He liked the work, gave me a call, and invited me to the gallery. They were showing Matana Roberts—she’s a composer. A real GOAT [greatest of all time]. In terms of the jazz world, I’d say she’s one of the greatest living artists.

TN: You have a background in music, too, right?

NL: I played the violin. I started my last year of college. I played from 2008 to 2014, then I just stopped because I got into visual art, and I didn’t want to split my time.

TN: Did music leave an impression on your work as a visual artist?

NL: I don’t know if my interest in visual art came from that, but I think when I started playing the violin I started tapping into the right side of my brain. Honestly, I never did any art growing up. I didn’t draw for the first time until 2010.

TN: How did you make the switch from being a nurse to an artist?

NL: When I decided I was going to make the switch, I had the confidence and vision [that] it was going to work. When I first started working with paper, there was a time when—just after making a few cuts with a certain technique—there was something I knew … was going to resonate with people on an emotional level. So when I quit [nursing], I wasn’t anxious about the transition into working as a full-time artist.

I’m just starting to get into the interior of what my art practice can be. I’ve mainly been working with paper and photos. I’m … going to keep digging into paper because it’s a charged material for me. I got into working with paper from working first with electrocardiogram rhythms—heart rhythms from patients [whom] I took care of.

These heart rhythm strips would print whenever the patients’ heart rates hit a set limit. We’d set high and low limits, depending on the patient’s condition and what was wrong with them, and then there are also rhythms that print when the heart rate is irregular, [which] can lead to further complications or be a symptom of something that we should check out further.

I would paint in the little gridded boxes, each box represented 0.04 seconds, and put sheet music and patterns behind them, but they weren’t archival so months later they started to form dots and shit on them, and I was heartbroken. All I wanted to do was work with those heart rhythms. Someone I consider family and a mentor of mine, Stan Squirewell, recommended I scan them and blow them up big. That way I could do what I wanted with them. So, from there, I printed the rhythms out big and started using layers of paper under them, cutting into them, and then I … simplified the process by [using just] the single sheet of paper, which was the rhythm itself, and that was the genesis of my exploration into paper. Really, the reason I started working on paper is because of the rhythms.

Nate Lewis, “Signaling 15,” 2019, hand sculpted inkjet print, ink, frottage, graphite, 40 x 26 inches [courtesy of the artist]

Nate Lewis, “Signaling 26,” 2020, hand sculpted inkjet print, ink, frottage, graphite, 50 x 44 inches [courtesy of the artist]

TN: Can you talk more about your technique of cutting and creating patterns on top of photography?

NL: The interruption of photography, for me, is all influenced by the diagnostic lens we would use when I was a nurse. There were hundreds of ways to see the unseen. The output of images and their density [were] a language. It’s all about subtle changes that you have to pay really close attention to. Those images determined everything. The images were all about understanding. We would have thousands of lenses, and all of them were for understanding how to care for a person. And it’s interesting because if there’s a cardiologist (heart); a pulmonologist (lungs); nephrologist (kidneys)—what’s good for the kidney isn’t good for the lungs, or what is good for the heart is not good for the kidneys or the lungs, sometimes. So they cared for what they cared for but had to negotiate and find balance within the [patient’s] plan of care. It’s all about these lenses and their different ways of seeing the depth of the body.

It’s really tied to thorough assessments. And that’s with whatever I [apply them] to. I did a piece for Untitled, ART Miami Beach where I took images of a Jeb Stuart monument in Richmond, VA—which is one of the controversial Confederate monuments that are under attack. With that piece, I’m thinking about the specificity of the monuments and the truth locked up in them. I’m turning stone to flesh. So I stripped it down to show the anatomy of the horse and took the monument, beyond [being] a rock structure, to be a penetrable, permeable, vulnerable narrative—playing with elements of the stories and their ideologies being eroded away. So, for me, [the work is] about thinking about what it means to understand these times [through] diagnostic lenses, which means critical thinking, nuanced ways to see things, seeing the unseen, allowing things to be complicated.

TN: This is a different way to process things like monuments and our history, but it’s also overall a conversation people tend to shy away from.

NL: Yeah, it’s because I started out thinking from a medical point of view. I wasn’t so aware of the frameworks or lenses that other people were looking [through]. But I’ve definitely changed things that I’ve done from before I moved here [New York], and even when I first moved here, like when I was [in residence] at Pioneer Works.

I have a piece [from 2017 in which] I show the intestines coming out of a Black figure [that I made] shortly after I stopped working as a nurse. I sculpted the intestines in the white paper. It looks like embroidery or fabric, almost, so it looks aesthetically pleasing. It’s subtle. The piece is black and white. Visually the piece is beautiful. I wasn’t thinking, Oh, I’m committing violence on this person. My association with working with paper is [as] a repetitive process. I have a sensibility and care for it. My [process/technique] in and of itself is an empathetic and caring one. I associated seeing and caring for the insides of somebody as the highest level of care. A deep care. Showing organs next to a figure, for me at the time, was about caring for [the figure] and understanding it. I was still in my nursing mode of thought.

I’m not making work like that, with Black figures anymore. My process [for] how I interact with figures has changed continuously. The first images I worked with were self-portraits. [In one,] half of my torso looks like it got a chunk taken out of it. I have another self-portrait that looks like my whole upper body is being cut open from the middle. That was just my world, and incising and cutting the body and taking care of the physical body and interacting with it meant a deep care. It was just honest work that I made without any knowledge of what people would think of it. I was in the medical world. I didn’t know that people would think it was violent or self-mutilating. Or that people would think I was troubled with myself. It was the complete opposite. I was thriving. Things were clear, and I was very in tune with myself.

Nate Lewis, “Static, Cymbals, Vibrations,” 2018, hand sculpted inkjet print, 26 x 40 inches [courtesy of the artist]

TN: How did you come up with the concept for Latent Tapestries?

NL: From thinking about visualizing tissues of the body—the medical lens output imagery, the different layers of tissues in the body, the organs and their tissues, how all these layers interact through networks of blood vessels and lymphatic systems, and electrolytes, and hormones. The sounds that can be heard within the body, the different textures of the sounds: [there’s] a musical composition within. I think about music and sound like textures. They influence how I create … the feel of them, the movement of them. I think about history, and movement, and migration, and data, and maps, and all the networks and paths that interconnect and affect one another as separate and connected tapestries. These ideas influence my work. My finished works come about through pulling out texture from a piece of paper; the feel is textural, and the look is tapestral.

TN: Will this work embody your style of viewing the subject through diagnostic lenses?

NL: Yes, that’s my language. How I assess and the reason I interrupt images [is] linked to my thinking about how history is made up of patterns, and [how] a mode of teaching is following these certain patterns. I think about patterns in everything … how they determine what we understand, what we’re familiar with and not familiar with. Those ways of thinking affect our neuroplasticity and the different pathways in our brains …. That’s where I realized that I, and many people, were taught history [as] a pattern—one that’s not of care for a lot of people …. So, me creating my own language and my understanding of assessment [are how] I understand history now. And to put this language onto work is to undo the patterns that were presented. It’s undoing and disarming those other ways of understanding.

TN: And it sounds like you’re expanding the mediums you work with in this show. Is that right?

NL: Yes. I’m doing a sound installation. I was trying to think about ways to accent the work beyond just painting a wall or [an] area around my work.

My favorite pieces I saw this past year were sound pieces. One was at the High Line [in New York City]. Claudia Rankine was one of the writers for it. It was called The Mile-Long Opera: a biography of 7 o’clock, and it was hundreds of people singing that played randomly throughout this long walk. They were from all different walks of life, all different ages. That one really resonated with me. Then there was this piece at Pioneer Works when I was there, Four Simultaneous Soloists, [wherein] David Grubbs presented [in conjunction] with Anthony McCall’s light works. That was a really transforming space that stuck with me.

Nate Lewis, “Probing the Land 4,” 2020, hand sculpted inkjet print, ink, frottage, graphite, 44 x 60 inches [courtesy of the artist]

NL (cont.): So, back to the show: I didn’t want to paint a wall. I want to be as minimal as possible, but intentional. And I was thinking, with the element of taking care of people, there’s diagnostic imagery, and then there’s this subjective thing, which is what the patients are saying. That’s diagnostic sound. So, we listen to what is being said. Then there’s also ultrasound, which is seeing an image because of sound vibrations. I read this article in the New York Times, “Visionary Musicians Seek Truths for the Future in a Spiritual Past.” It was, like, Oh, damn, musicians are trying to communicate the same ideas that we, as visual artists, are, but through sound. And I let that be a bit of a guide for the musicians I wanted to work with in my show. So, there’s Ben LaMar Gay; Matana Roberts; my friend Luke Stewart, who [sometimes collaborates] with Moor Mother; Kassa Overall; and Melanie Charles, [who] will be featured in pieces in this installation.

I’m thinking about how I’m having Black figures in the room, and I really dove into thinking about music in a different way. It’ll be a little bit jarring, and I want it to be, because the sensibilities these artists have are really incredible.

TN: You mentioned you’ve been working on your monument pieces for this show as well. How will they illustrate this idea of assessment through patterns and, potentially, sound?

NL: The monument conversation is a complicated one with many different angles. I try to show this complication [through] elements of editing, altering, distorting, and showing them physically wounded. There’s a lot of precision and intentionality in all of the cuts and marks I make on the pieces. With the monument pieces, I’m just trying to show their current status in the climate of society. [While] thinking about the energy and efforts that are directed at them to have them removed, I sculpt an anatomy into them—turn stone into flesh to show them as vulnerable. In one of them, I cut away the stone protection of Stonewall Jackson, paint in lungs and intestines that are exposed, as well as render him ghostly on the horse. In that same piece there are intestines that are falling out of the horse. They say that their history is being gutted, so I’m just showing that.

The power of these monuments across the land, and the ideologies they represent, are more vulnerable than ever. I’m just activating them in my own language, putting them in a state of limbo and impermanence.