Nacional Insufficiencies

Cynthia Gutiérrez, Inhabiting Shadows, 2016, Metal scaffolding staircase ascending and descending the pedestal where Lenin’s statue once stood, 248.03 x 59.06 x 550.79 inches [photo: Sergeev Dima; courtesy of the artist and Izolyatsia Platform for Cultural Initiatives]

Share:

In a past issue of ART PAPERS, Emily Wilkerson’s Imagine New Monuments: A Case Study of Paper Monuments studied the New Orleans–based Paper Monuments, a collective effort to reclaim the histories of local heroes as well as an initiative to highlight the “complexities and layers” of the Civil Rights Movement in the city and, more generally, the US. Acknowledging that text is important because it opened a conversation that (almost serendipitously) continues here. Wilkerson’s essay participates in heated conversations about the presence and permanence of Confederate monuments—ones particular to New Orleans—and otherwise present throughout the US with greatest concentrations in the Southern and East Coast states.

In many other cities of the Westernized world, recent years have brought a continual questioning—perhaps too internal to contemporary art, and in too few cases externalized into other social spheres—of the increasing insufficiency of existing memorials. Whether they address national identities, foundational myths, celebratory memorializations, commemorative constructions related to particular communities, or social/political events, questions such as the following must arise. Who is represented? Who has been left out? Who is telling the story? Who is listening? Ultimately, who are these spaces failing to represent or erasing? Do our current memorials reveal or preserve the imbalances from colonial models—of inhabiting the public space amid ongoing fights for social justice and visibility for diverse voices in history?

In various Latin American countries—ones where an ontological condition of underdevelopment, along with consequences of colonialism and influence from early 20th-century socialism hold influence—public spaces are even more derivative of old European models. In cities where the Eurocentric notions of urbanism and shared space prevail, these public symbols are perhaps a secondary concern when more pressing matters remain unresolved. The stories of Spanish conquistadors mashed up with independentist heroes and revolutionary leaders crowd public spaces as statues, busts, and rotundas.

Cynthia Gutiérrez, Inhabiting Shadows, 2016, Metal scaffolding staircase ascending and descending the pedestal where Lenin’s statue once stood, 248.03 x 59.06 x 550.79 inches [photo: Valeriy Miloserdov; courtesy of the artist and Izolyatsia Platform for Cultural Initiatives]

Thinking about this, I present two short conversations with Cynthia Gutiérrez (b. 1978, Mexico) and Carlos Motta (b. 1978, Colombia). In her artist biography Gutierrez describes her artistic practice as a more deliberate effort to articulate “historical elements from a new posture with distorted chronologies that evidence the impossibility of generating accurate memories and reveal the transience of history.” Motta describes himself in his biography as “a historian of untold narratives and an archivist of repressed histories.” It’s fair to argue that both artists profess an interest in rearticulating hegemonical versions of history to acknowledge the layers and complexities of the narratives discussed in their projects, and to recount the other side—silenced voices, suppressed discourses, or erased memories.

Gutierrez’s practice is perhaps more rooted in sculpture and artistic gestures—actions and interventions that point to external references which then establish a dialogue with the work of art. This strategy is clearer in such works as Patria (2016), a site-specific intervention at the Museo de Arte Raúl Anguiano in Guadalajara. The artist carved a hole through a museum wall, which at first glance just appeared to be an irregularity in the architecture of the room. A closer look through the orifice allowed viewers to see one of the city’s oldest and biggest monuments. It is dedicated to los niños héroes (the boy soldiers), a Mexican tale about young cadets defending the Chapultepec castle in 1847, in the midst of the Mexican-American war. In 2016, Gutierrez made a project in Kiev that consisted of an intervention onto a platform where a Lenin statue once stood. After the demolition of many of Lenin monuments in Ukraine after 1991—a salient reference for the aforementioned discussion about Confederate monuments—many of these public spaces remained empty. Gutierrez’s strategy was to create a scaffolding staircase, where new bodies could literally climb up and occupy the space where the statue once stood.

Motta has produced highly symbolic, documentary pieces that document “the social conditions and political struggles of sexual, gender, and ethnic minority communities in order to challenge dominant and normative discourses through visibility and self-representation.” Revisiting a subject or creating iterations of the same project, Motta often uses diptychs, triptychs, or more complex formations such as trilogies. The human body is constantly present in Motta’s practice. Anchored in explorations of his own body, or the voices or bodies of others as they recount stories, Motta’s work is able to encode a human dimension, although it is not always delivered immediately. In 2006 Motta created the Leningrad Trilogy, a meditation (almost in the way Walter Benjamin refers to the detached observations of the flâneur) upon Saint Petersburg and the Soviet Era monuments, through which he revises— not only the space, but testimonies about—two of the most important monuments to Lenin. This point of contact between Motta and Gutierrez—apart from their being born the same year and belonging to the same generation—is that both artists have highlighted the strong connections between the framing of public space within Socialist regimes and the legacy of Socialism within revolutionary movements in Latin America.

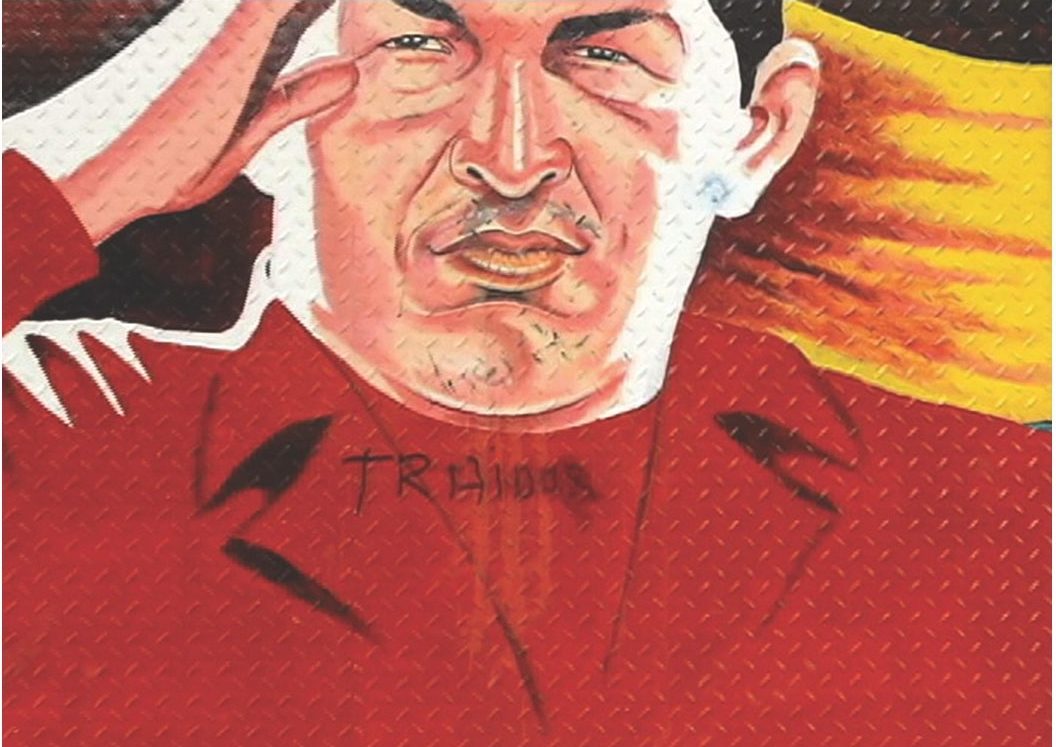

Ideological Monuments/Historical Relations is a series of eight photographic triptychs in which the artist reveals a disparity—a conceptual discrepancy—between monuments erected in cities of Chile, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Panama, Bolivia, Guatemala, and Mexico among others. Motta juxtaposes images of public constructions and spaces. Some honor social justice heroes or feature Catholic iconography. Others are abstract monuments dedicated to such subjects as justice, revolution, students, or guerrillas. Other images in the series show the back of a bust or a detail from a mural. The last image in the series depicts a Hugo Chávez mural in Caracas, Venezuela, that has been tagged with the Spanish word for “traitor.”

Carlos Motta, Ideological Monuments / Historical Relations # 8 (Traitor—Vandalized mural depicting Hugo Chávez (Caracas)), 2012, 11 x 9 inches [courtesy of the artist]

CARLOS MOTTA

Humberto Moro: In projects like Ideological Monuments/Historical Relations (2012) you created a kind of collection, a vocabulary of public space which revealed some of the complexities of symbols of nationalism via monuments in the streets of Latin America. What do you think the traction of these symbols in today’s world is?

Carlos Motta: The world is saturated with memorials to institutionalized forms of oppression in the form of erect men displaying symbols of power. Thankfully, a movement of resistance against these uncritical models of commemorating has formed internationally, sparking conversations about symbols of might as symptoms of a diseased society. Today, we aren’t only critical of memorials, but we also feel empowered to propose alternatives to the tired bronze-white-man-on-a-horse model or historicizing.

HM: Something that strikes me about your working process is that you articulate the many experiences of having traveled through cities in Central and South America, as well as incorporating into your works the voices of citizens and noncitizens of many regions, including the Middle East. Can you talk about this sort of polyphonic mode of operation?

CM: I believe the (self) representation of real-life stories is the most effective mode of addressing the dire social and political conditions that affect bodies, populations, and societies in the present. I have employed the video interview and portrait because they represent unique opportunities to articulate “speech acts” collaboratively. This process is based on communication with the subjects I work with. Together we devise a strategy to tell and distribute their stories within a controlled context, such as an online archive or an installation framed by rigorous conceptual out-and-inlines.

Carlos Motta, Ideological Monuments / Historical Relations # 1 (Monument to Óscar Arnulfo Romero (San Salvador), Monument to the Nameless Guerrilla Soldier (Managua), and Monument to Justice (Tegucigalpa)), 2012, 27 x 9 inches [courtesy of the artist]

HM: Is it fair to say that in the 2000s your work addressed more frontally issues of colonization, subjugation, and insurrection in Latin America, particularly in the public space, whereas more recently your research has focused on addressing issues of social justice in relation to sexuality and gender? And, if so, would you say there is a correlation between the latter and the recent rise of far-right regimes?

CM: Throughout the last two decades I have been interested in how the colonization of territories and the imposition of ideologies have affected bodies and identities, both individual and collective. My earliest projects focused on the relation between Latin America and the US—a complex relationship based upon exploitation on many levels. I have always been interested in the issues of class, race, and ethnicity, but I have come to understand that these are always intersectionally linked to gender and sexuality, and as such they need to be discussed together. It is true that my most recent project focuses on the politics of gender and sexuality, but not exclusively. I am interested in exposing the intricate web of power relations that constitute the field of representation.

HM: Do you think monuments as a format have any future? If you could imagine new forms of collective representation in the public space, how would these be?

CM: The model of the monument isn’t future-less, but our approach to thinking and making them needs to be updated to reflect different voices and experiences, and collective concerns. Monuments become emblems, and emblems should reflect the intersectional and very diverse experiences that take place in public space.

Carlos Motta, Ideological Monuments / Historical Relations #4 (Monument to Salvador Allende (Santiago), Monument to the Constitution (San Salvador) and Monument to the Soldier (Tegucigalpa)), 2012, 27 x 9 inches [courtesy of the artist]

CYNTHIA GUTIÉRREZ

Humberto Moro: In your work, you often use objects and symbols which are associated with ideas of nationalism and identity. Could you describe why you choose to work with these objects, and why you think it is important to speak about these subjects?

Cynthia Gutiérrez: Do we exist only in the present time? What of our existence in the past? Does our existence in the past have meaning? Can a woman or man be defined by one single moment? Can an individual be defined separately from his or her context, from the world he or she lives in? Identity and memory are concepts that intrigue me. So does the notion of nationalism, which takes the idea of identity to a collective level. It seems like the human being needs to belong to something greater than himself—otherwise he’s lost. This need makes him vulnerable to power and manipulation. The construction of collective memory through monuments—more than being the result of the identity of multiple, diverse, different people—is the result of humans’ pursuit for power, which is one of the main problems of nationalism. It is not about roots, history, diversity, community, or identity. It is about containing, retaining, constraining, secluding, confining, and building an illusion of a world that only functions within the borders. Freedom and justice are not the priority in these power structures controlled by only a few. This is the reason why it is important to speak, question, and discuss these issues, for the real essence of humanity is being forgotten.

HM: Unlike other artists whose practice is more localized in a region, you don’t speak about one kind of nationalism. Instead, you work fluidly between different nationalisms, and you identify their commonalities, or the commonalities within their failures. Could you speak about this?

CG: I believe that when a material or structure is rigid and inflexible, it is more likely to fail. That is what nations have built: fixed models, rigid prototypes. I think that through my work, I do speak from where I stand. There are certain traits—certain materials or techniques—that are the result of or that reveal my immediate context, but I believe these topics, although different in form in different times and places, have a common ground. So, I believe that a very particular conflict can be understood universally.

Cynthia Gutiérrez, El fracas del liberated, 2014, bronze, 22.4 x 30.71 x 20.08 inches [photo: Lake Verea; courtesy of the artist and Proyecto Paralelo]

HM: Could you describe the thought process behind Inhabiting Shadows?

CG: IZOLYATSIA Platform for Cultural Initiatives made an open call for temporary interventions. My project Inhabiting Shadows was selected. It consisted of building a scaffolding staircase that went up to the top of the pedestal where the statue of Lenin once stood and then down [again]. The idea was to build a structure that allowed people to transit up the stairs, step on the pedestal, and occupy the empty space for a moment—to be able to reflect upon the past, to substitute the phantom, the shadows, inhabit them and then become new and diverse moving statues that headed towards the light of a new horizon. A temporary monument integrated onto the remains of an older monument, which was not about the visible structure, but mostly about the people transiting it. A sort of monument in construction where everyone was a part of the identity that changes through time and with people.

HM: The notion of what a monument is, or should be, has shifted dramatically in the past decades. Could you describe how/if you envision the future of this format?

CG: The notion of monument as grand, solid, unbreakable, and permanent definitely needs to change. It is because of fixed ideas by imposition that men do not evolve, cannot relate, are unable to understand each other, are incapable of recognizing what is different. I believe that a work will truly be monumental when it aims to include all people. When it is able to change as identity changes. It is a great challenge to rethink public space, and to conceive new ways and formats to reminisce.

Humberto Moro (b. Guadalajara, Mexico, 1982) is deputy director and senior curator at Museo Tamayo, Mexico City; curator at EXPO CHICAGO; and adjunct curator at the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, where he has organized solo exhibitions by such artists as Oliver Laric, Liliana Porter, Cynthia Gutiérrez, Pia Camil, Mariana Castillo Deball, Tom Bur, Yang Fudong, FOS, AES+F, and others. Previously, Moro held positions with ZONAMACO and Museo Jumex in Mexico City. He has curated projects at El Museo del Barrio, Park Avenue Armory, Johannes Vogt Gallery, and the Hessel Museum of Art in New York; La Casa Encendida in Madrid; and Museo de Arte de Zapopan in Guadalajara. Moro holds an MA in curatorial studies from the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College.