Myriam Ben Salah: Missed Connections

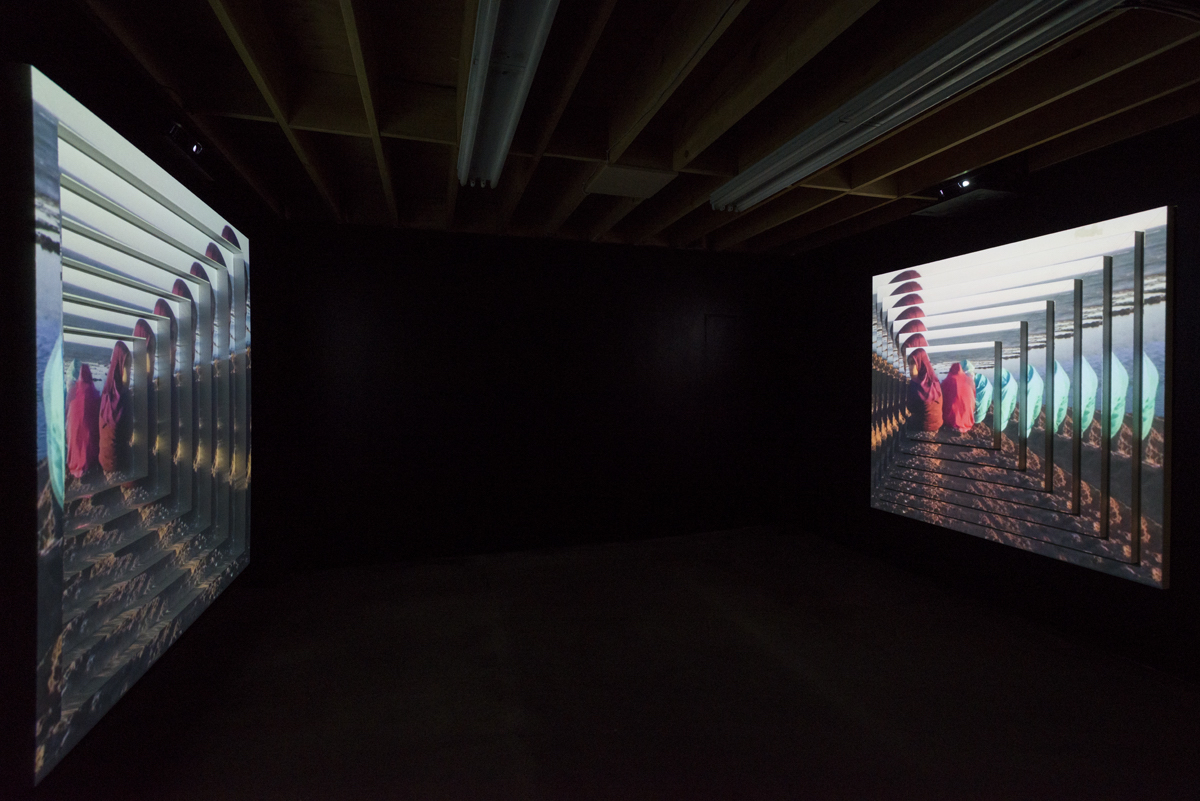

Myriam Saleh, Cool Memories, installation view, 2016 [photo: Anatole Barde; courtesy of the artist and the Occidental Contemporary, Paris]

Share:

Exiles always find one another in crowded rooms. Myriam Ben Salah and I first met last fall in Milan at an event for Kaleidoscope, an Italy-based, English-language magazine for which she served as editor-in-chief, starting in 2016; currently, she is its editor-at-large. In the space of 60 seconds, I witnessed her speak Italian and French, field a short call in Arabic, notice a tattoo of Samuel Beckett on my arm from several feet away, and then walk over to greet me in English—or at least that’s how I remember it happening.

Myriam was born in Algeria, raised in Tunisia, and educated in France. She moves between several cities to work as a writer and curator. She is currently co-curating the 2020 edition of Made in L.A.,1 alongside Lauren Mackler. Between jet lag and frequent time zone changes on both sides of our conversation, we sat down to talk about the impact of exile on her endlessly mobile, polyglot curatorial practice.

Mahfuz Sultan: Let’s start with language. How many do you speak?

Myriam Ben Salah: I speak five languages: French, Arabic, English, Italian, and Spanish. My friend—the curator Nadja Argyropoulou—keeps talking to me in Greek, convinced that I understand, but I actually don’t. We should have a Mediterranean Esperanto.

MS: There was! There used to be a Mediterranean lingua franca that all the sailors spoke, a mix of Greek, Arabic, Turkish, Spanish, Italian, et cetera. What language do you dream in?

MBS: I dream in French. But I get angry in Arabic.

MS: And you work as a curator in all of the languages to a varying extent, right?

MBS: I do. From very early on, I had to learn to adapt. When I was six years old, my family moved from Tunisia to Belgium. The French school there rejected me because I barely spoke French at the time (I grew up speaking Arabic). I still remember my mother crying when I got rejected. I ended up in a Catholic Belgian school—you know, because they have to accept everyone. Talk about adaptation! I promised myself I would never make my mother cry again and have tried since then to speak my interlocutor’s language.

Take Italian for example, I never learned it formally, never took any classes. In 2011 I started hanging out and collaborating with artist Maurizio Cattelan and the TOILETPAPER magazine crew, and I ended up speaking their language. Out of interest, out of empathy, and to be able to be as close as possible to their creative process. Things get lost in translation and I want to know the people I admire in their original soundtrack. We tend to use English by default, but that is a bit lazy and makes so many things slip into the cracks. It’s not always easy. You speak several languages as well, right? Don’t you feel that you’re a different person when speaking each one of them?

MS: I really think they’re all just one broken language at this point. I hardly speak Arabic anymore and I still instinctively speak it sometimes around my father, without realizing it. I often dream in Amharic. I curse in French.

MBS: I’m personally way funnier in French. I feel you about the one broken language; I’ve had the same feeling recently. I sometimes suffer linguistic schizophrenia but ultimately I feel lucky to be able to navigate these different frames of reference. Language shapes thoughts, so changing languages is a healthy form of mental gymnastics that allows me to change my frame of reasoning all the time. It gives so much distance and perspective on things, and it keeps me from getting comfortable in terms of thinking, which I believe is crucial. When I’m in France I think like an Arab, when I’m in the US I think like someone French, when I’m in Tunisia I think like a stateless soul.

Myriam Ben Salah, Cool Memories, installation view, 2016 [photo: Anatole Barde; courtesy of the artist and the Occidental Contemporary, Paris]

MS: Discussions around refugees, exile, et cetera, tend to revolve around travel between the MENASA [Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia] regions, and then Europe and North America. However, having grown up in the Middle East, I know as well as you do that dispersal and movement within the region itself is a central fact of life there, and perhaps the more significant historical question. Can you help me think a little about terms like “diaspora,” “migration,” “exile,” et cetera, and how that impacts your practice, especially given how much you continuously travel around the regions?

MBS: I went to see a therapist once and described myself to her as a nomad. She said, “Well, nomads travel in a tribe. You don’t. You’re in exile.” I had to go see another therapist to get over that. [laughs]

My grandfather spent most of his life in exile. He was a Tunisian politician and trade union leader who tried to implement his ideas for a planned economy. He ended up tricked by his detractors and condemned to 10 years of hard labor. He managed to escape from his prison in Tunis, dressed up as a woman, and fled to Algeria, where he lived as a political refugee—then Switzerland, Austria, Sweden, [and] France, where he was allied with the international left powers.

That might have influenced my sense of place and displacement. After I moved to Paris from Tunis, 15 years ago, I didn’t identify with the Tunisian diaspora. At the time I was so happy to leave—the dictatorial and corrupted regime of Ben Ali, the bourgeois environment of the Lycée Français, my (dis)comfort—that I fully immersed myself in Frenchness. I had never defined myself primarily as “Tunisian” or “Arab” (or as a woman, for that matter), and it was never a prism that I looked at things through. An “Arab” in France is much more of a social status than an ethnicity. Coming from a rather modest but still “bourgeois” background in Tunisia, I wasn’t identified as “beur” [a nickname for French people of Northern African descent]. So I always felt like a rootless cosmopolitan with very little knowledge about the politics of identity. And then the Charlie Hebdo attacks happened in France, and suddenly I “became” Arab in the eyes of others. I was asked to speak up for “my community,” to condemn the acts of “my peers.” I realized you can’t escape identity, and it became an interesting subject of study in and of itself.

I find it interesting how all the terms you describe are actually ruled by a class system: the diaspora is seen as the higher class, the migrants who made it; migration is the low-income foreign population that nobody wants; and the exiles are the political class. Reality is way more complex than that.

MS: To my mind, you were among the first curators after the Arab Spring to swerve away from questions of conflict, chaos, post-9/11 doom and gloom towards a lighter, pop aesthetic. One that used humor and irony to poke fun at contemporary life in the regions, particularly in the Gulf states. Can you go back to that time a little bit and describe it?

Portrait of Myriam Ben Salah [photo: Ilyes Griyeb; courtesy of the artist]

MBS: I always quote “The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents,” an article published in Artforum’s February 2006 issue, where art critic Claire Bishop states “the typical Western viewer seems condemned to view young Arabs either as victims or as medieval fundamentalists,” describing the media’s selective production and dissemination of images from the Middle East. I think it is precisely the same situation right now in France, although the postcolonial ghost makes the situation quite specific. Right now, young Arabs in France are either demonized as potential terrorists or victimized as submissive individuals (aka women).

I guess I’ve always been fascinated and saddened by the way a region with such a rich cultural legacy has traditionally … been looked at only through the prisms of failure and conflict. There is usually little attention paid to pop culture within the region: the wit and the humor, the irony and the irreverence, the sensuality and the kitsch. Middle Eastern or North African culture does not tend to be associated with laughter and levity in the global imagination. The West has alternately romanticized and fomented fears of the Middle East, keeping it a “serious” subject matter. I am not saying it isn’t or that trauma shouldn’t be a subject in art, but I feel like some artists have been obsessed with struggle narratives and a rhetoric of the past, creating works that were almost a response to a tacit commission, arbitrarily linking authenticity with traumatic backstory and storytelling.

Also, as you know, when you live in Morocco you hardly have anything in common with someone from Kuwait. You barely understand each other’s dialect, and yet you belong to the same imaginary representation of a region. Tunisia feels more like Africa than [like] the “Middle East” to me. Anyway, I tried through my curatorial practice to contribute to the deconstruction of the outlines of that imagined “Middle Eastern” aesthetic and to playfully question the stereotypes. I’ve worked with artists—… Meriem Bennani, GCC, Sarah Abu Abdallah, et cetera—who digested both the rich cultural history of their respective countries and the contemporary connected world that we live in. They are not rootless, but they defy any presumed homogeneity or audience expectations.

MS: What about Tunisia and its contemporary art scene?

MBS: Before the revolution of 2011 in Tunisia, no one could talk, no one could think, no one could even dream out loud. The corrupted dictatorship kept the contemporary art scene within a straitjacket for too many years. When the revolution happened, there was an outburst of creativity. It was abundant, it was messy, and it was necessary. These past [few] years the scene has been structuring itself, with new, artist-run structures popping up (B’chira Art Center, Association l’Art Rue), or spaces funded by bigger foundations (B7L9 by the Kamel Lazaar Foundation), citywide events [such as] Dream City or Jaou Tunis, and galleries being more present on the international scene (Selma Feriani Gallery, Elmarsa, Gorgi, et cetera). I think what’s lacking right now are exchanges: sending Tunisian artists out and bringing international artists in. It is something I’m currently invested in through collaborations with B7L9 art station.

MS: Rather than cultivating a specific area of expertise, you have worked through long-term, evolving relationships with a set of artists … dispersed all over the world. It seems that curatorial practice and friendship are inextricably linked for you. Is there anything that ties them all together?

MBS: I see the role of the curator as a companion to the artist: a conversation partner, an ally. My friendships always came after my interest in someone’s work. I don’t work with my friends, but I become friends with the people I work with. I am deeply attracted towards people who are intelligent to a point that I almost can’t comprehend, people … I will be constantly learning from. I think friendship is the best form of collaboration because it allows exciting ideas to permeate everyday life. There is also this notion of creating an intellectual gang. In an environment that’s more and more individualistic, it feels important to stake the claims of a generation and to foster informal conversations about important projects.

Their practice reinvents a language that’s new for me to learn. I think that’s probably what ties all these wonderful humans together. They are brilliant minds, unafraid of the complex and the morally ambiguous; they cultivate nuance and complexity in their practice, and they experiment with form. Oftentimes they are also people [who] question the art world as a system and are open [to] other realities. They have a true sense of community and support.

Myriam Ben Salah, We Dance, We Smoke, We Kiss, installation view, 2016 [photo: Jeff Mclane; courtesy of the artist and Fahrenheit, Los Angeles]

MS: Can we digress for a moment and talk about Bidoun and the broader group of artists it put in conversation? I definitely feel—to a certain extent—like an intellectual child of the publication. I know that you have close relationships with several of the artists they have collaborated with over the years ….

MBS: I’ve been a longtime fan and diligent reader of Bidoun magazine, which after 9/11 had started to carve a path for contemporary art within the loosely defined region of the Middle East with a perspective that felt irreverent, very often funny, surprising, and almost always personal. The magazine created what I call a “vernacular disorientalism,” decongesting the stigmatized visions of the region. I love that they were able to talk with equal intellectual rigor about Gulfiwood, Hafez al-Assad’s Iron Bladder, Cat Stevens, Naguib Mahfouz’s white linen suit, Egyptian gangsta rap, Pakistani horror porn, Iranian pop music, and Larry Gagosian’s Armenian origins. They offer stories from the perspective of almost (but not totally, or maybe not at all) native informants—or at least those “who grew up speaking multiple languages, maybe all of them badly,” as my dear friend and Bidoun’s senior editor, Negar Azimi, puts it. See, it always comes back to language.

MS: And now Made in L.A.. What does it mean for you to curate a show of primarily American artists in an American context? How do you “think” America—or, more specifically, California—in the context of a museum?

MBS: California is a place that feels familiar in relation to my upbringing in Tunis (the climate, the car-dominated lifestyle), but also so strange in the way it epitomizes all of America’s contradictions. Los Angeles feels like a third world city; the backstage of its perfect sunrises and beaches is dark and messy. I came to Los Angeles for a residency program in 2016, and I was struck by the physical and mental space that the city offered (compared to Paris, for example). The cliché of the last frontier is somehow relevant, at least at first sight. One has a feeling that anything is possible in LA.

I am personally fascinated by the relationship Los Angeles entertains with fiction, and I feel like my work on Made in L.A. has been a quest for reality where they manufacture make-believe. I’ve been revisiting Jean Baudrillard’s thoughts on hyperreality because the misrepresentation of what’s real drives that city’s most prominent industry, the movies, and everyone aspiring to belong to it. I think this will manifest in the work that we’ve been doing with Lauren around the exhibition.

However, as much as I thought of myself as a product of an American-dominated globalized world, I never thought there would be such a culture clash in working in the United States. Conceptions and perceptions of identity, of representation, of integration, of property and appropriation, of morality, of nuance are so different from [what they are in] France or … the rest of the world as I know it. That was definitely a challenge for me. It was as enriching as learning a new language.

Myriam Ben Salah, We Dance, We Smoke, We Kiss, installation view, 2016 [photo: Jeff Mclane; courtesy of the artist and Fahrenheit, Los Angeles]

MS: You have a very close relationship with several Los Angeles artists, as well as The Underground Museum …. Can you talk about that space a little? What about your experience more generally?

MBS: I watched Kahlil Joseph’s video “m.A.A.d” when it was at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in 2015, then I came across it again at Art Basel the year after, and I was like, “Who is this person making these mesmerizing films?” When we finally met, I had a million questions for him about his work. He eluded me entirely and asked questions about Tunisia instead, which I liked. Then he asked me, “Do you know about The Underground Museum [UM] in LA?” I didn’t.

Serendipitously, I was coming to LA a few weeks later, and I spent my whole summer at the UM, as we call it, watching movies screened in the Purple Garden and hanging out. I had never quite experienced anything like it when it comes to art spaces: what Noah Davis and his family conceived defies any expectations. The soulful place is constantly alive, and it is refreshingly not catering to the art crowd. I met the most committed people from the UM’s tight family circle, as well as many of the most brilliant creative minds in town. I always remember something Megan Steinman, the museum’s director, told me: “The UM is a magical vortex. If you hang out long enough, everyone you need and love will show up.” I remember watching Arthur Jafa’s first version of his acclaimed video Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death on Kahlil’s laptop in the museum’s kitchen and meeting the artist himself across from the UM’s bookstore. I remember sharing a smoke and scattered thoughts with the immutable Henry Taylor around the garden fire pit. I remember getting a ride across town from Deana Lawson while she was in residency at the museum and discussing the pictures she was shooting in Compton—[ones] that would end up at the Whitney Biennial a few months later.

The Underground Museum is also a place where I learned a lot regarding the issues I mentioned to you before. Honestly, the place feels like a home away from home, and I’ll be forever grateful to the family there for letting me in.

MS: To my mind, something like UM is inconceivable right now in Paris, certainly at that scale. If so, then why not? What are the possibilities for alternative/experimental art spaces in Paris?

MBS: The Underground Museum is a model for me in terms of audiences. I don’t think of it as alternative or experimental in terms of programming. The exhibitions organized there are ones that you could see in major museums or galleries. But it is the only institution … I know that understood how to bring art to larger audiences, truly, sincerely. You know, everyone is always talking about diversity in the artists presented in museums, in exhibitions. That’s important to a certain extent. But I think the focus should be more on diversity within the audience. Most museums, most galleries cater to a white, higher-income audience. Even alternative spaces, they attract people with a certain cultural capital. The Underground Museum created a space that raises the bar culturally while remaining comfortable, welcoming. A friend of mine once formulated it pretty well: “You can feel that they care.”

In France there is a fatwa against anything that has to do with communities, and what is called “communautarisme” is the object of a witch hunt. So I am not sure that something like the Underground Museum, with a focus on art made by or consumed by minorities would be possible. However, something interesting is happening in Paris right now where artists from second-generation immigration are creating a shift in narratives and taking control of how their production is framed, talked about, and distributed. I think about Mohamed Bourouissa, Sara Sadik, and Soufiane Ababri, for example. This might be the beginning of something, and it is something that I’ll keep on supporting as a curator and a friend.

Myriam Ben Salah (b. 1985, Algiers, Algeria) is a Tunisian French curator, writer, and editor based in Paris. France. She was in charge of special projects and public programs at Palais de Tokyo from 2009 to 2016, focusing especially on performance art, moving image, and publishing initiatives. Ben Salah is currently the editor-at-large of Kaleidoscope. She also co-edited FAQ, an image-only magazine, with artist Maurizio Cattelan, as well as FEB MAG, the publication of The Underground Museum in Los Angeles. Her writings have appeared in Artforum, Mousse, and Numéro. She is currently working on the Hammer Museum Made in L.A. Biennial to open in 2020.

Mahfuz Sultan is a writer, researcher, and designer living in Los Angeles.

References

| ↑1 | This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS Winter 2019/2020 “Global(isms).” At the time of publishing this interview on ARTPAPERS.ORG, the future of Made in L.A. at the Hammer Museum is uncertain, as the museum closed indefinitely due to the COVID-19 crisis |

|---|