Monuments Under Occupation

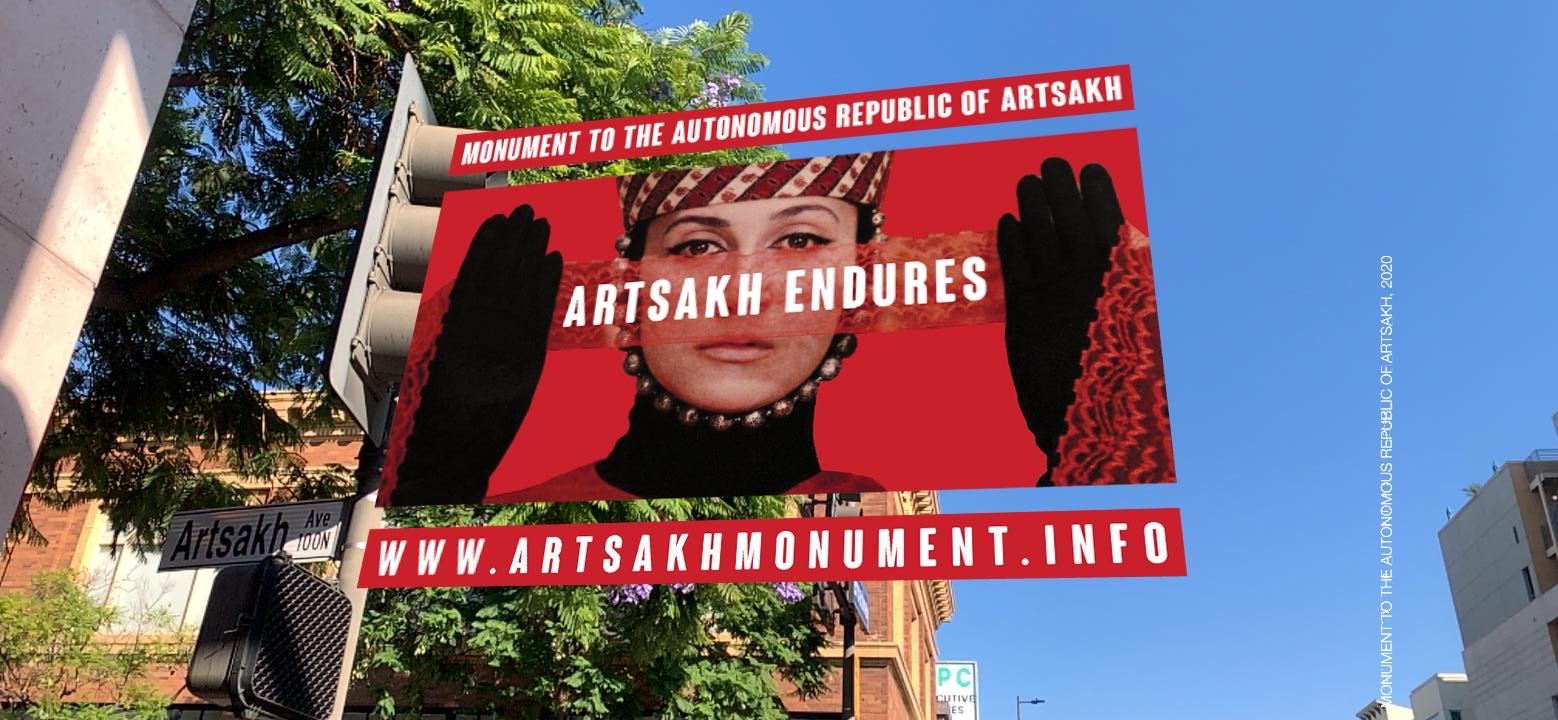

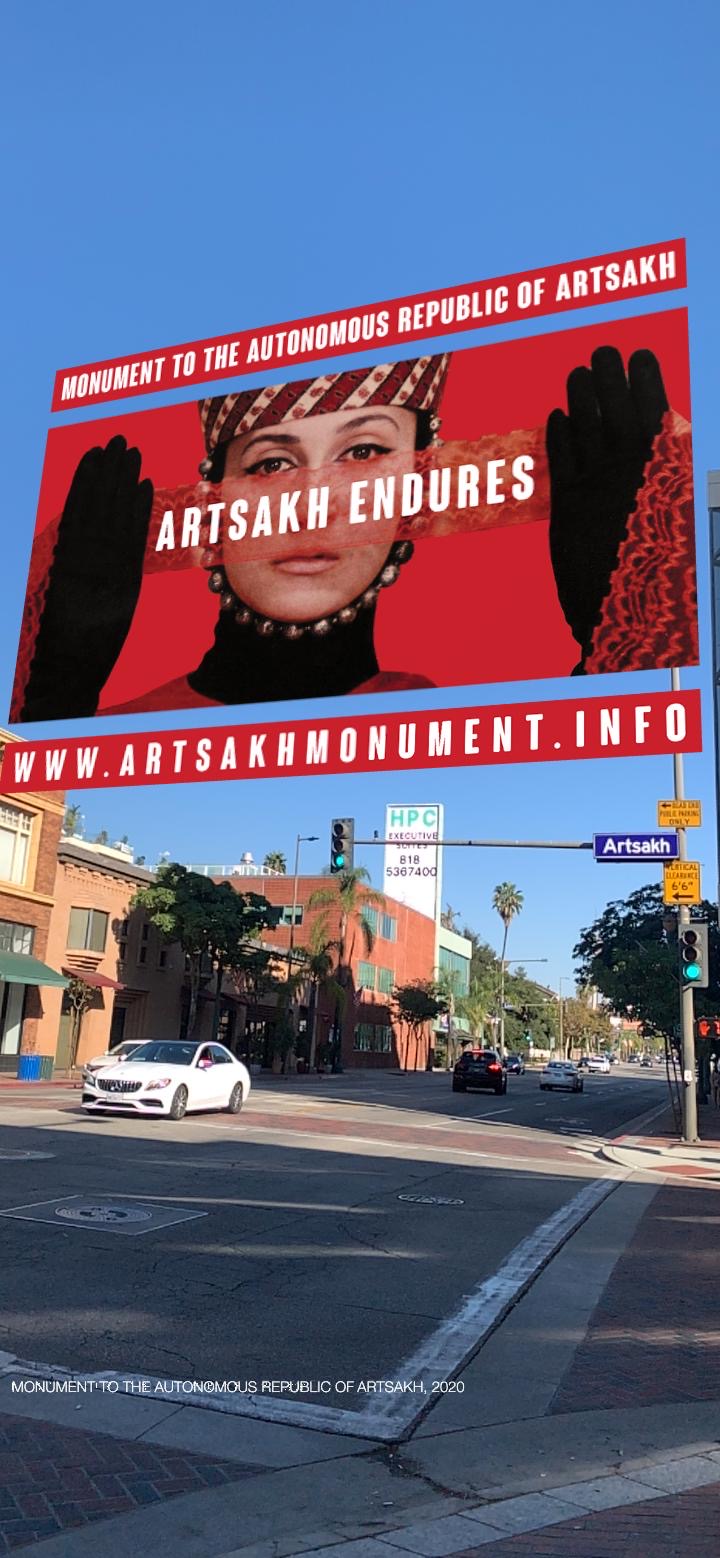

Kamee Abrahamian, Nancy Baker Cahill, Mashinka Hakopian, and Nelli Sargsyan, “Monument to the Autonomous Republic of Artsakh,” (2020), AR monument installed at Artsakh Avenue, Glendale, CA.

Share:

Monuments reaffirm the power and presence of certain communities in specific places. They possess the ability to stretch the memories of individual and collective identities into the future. This unique function of monuments likewise makes them useful sites for political resistance and social reform, as well as for iconoclastic gestures of neocolonial violence and cultural genocide.

In this conversation, Mashinka Firunts Hakopian—Los Angeles–based artist of the Armenian diaspora, researcher, and organizer—explains the ongoing attacks against Indigenous Armenian lives and cultural heritage in the Republic of Artsakh [being] enacted by the states of Azerbaijan and Turkey. The conversation builds upon current public debates around monuments and markers of memory by focusing on cultural heritage. Cultural heritage refers here to the physical objects (e.g., monuments, artifacts, and archaeological sites) and traditions that are passed on through multiple generations; communities depend upon their cultural heritage to be able to assert their continued presence. Erasures of a community’s cultural heritage are thus enactments of oppression, and in Artsakh such erasures are, quite literally, matters of life and death.

Patricia Eunji Kim: Over the past year and a half, conversations and controversies around monuments have occupied public consciousness, especially as activists have advocated for the removal of—and sometimes even toppled and destroyed—racist and colonial statues and markers. But of course, not all forms of iconoclasm are the same. In fact, I believe that the debate around monuments is incomplete without a discussion about cultural heritage. So I wanted to begin our conversation on Armenian monuments and indigeneity by talking a bit about one object that gets to the very heart of this issue.

As an art historian and archeologist of the ancient Mediterranean and western Asia, I’m really intrigued by one of the objects that has been particularly striking; called the Satala Aphrodite, it’s currently housed at the British Museum. What I noticed when I was visiting the museum on one of my many research trips several years ago was that, on the one hand, the British Museum acquired this object in 1873—about 42 years before the Armenian Genocide. And on the other hand, the object, which was “discovered,” and taken from what was Armenia Minor, is identified as coming from Turkey. At that time I was a graduate student, and I didn’t really think anything of it, because I didn’t know that Satala was in Armenia in 1873, so I didn’t put two and two together. It wasn’t until I returned home and was looking closely at where Satala was on the map that I realized this label—and the British Museum—were knowingly or unknowingly participating in what I see as a sort of systematic erasure of Armenian culture. So my question for you, Mashinka, as an Armenian diasporan, is: Can you talk a little about the Satala Aphrodite and what the object means to you personally?

Mashinka Firunts Hakopian: Well, in Armenia the statue is known as Anahit, the goddess of fertility, healing, wisdom, water, and/or war in Armenian mythology. The bust of Anahit is featured on Armenian beauty parlor logos, state currency, stamps. There was a campaign to repatriate the bust—launched in 2012 in Armenia by Armen Ashotyan, the minister of Education and Science at the time, with the support and involvement of the Armenian Youth Federation. Roughly a hundred protesters demonstrated outside the British Embassy in Armenia with posters of the goddess, chanting “Anahit come home,” and presented the British ambassador with a petition of 20,000 signatures requesting Anahit’s return. They also authored a letter asserting that historical justice requires that the statue be “repatriated and find refuge” in its country of origin. Some state officials in Armenia at the time characterized the repatriation campaign as a strategic spectacle with aims to influence an upcoming parliamentary vote by appealing to the affective charge that the Anahit bust holds for Armenian people.

Bronze head from a cult statue of Anahita, shown in the guise of Aphrodite

PEK: I want us to think about this movement to repatriate Anahit to her country of origin—in this case, Armenia—although modern-day Satala is located in a region that is internationally recognized as Turkish territory. I’m wondering if you could elaborate on why this bronze head—why Anahit—is so important to the Armenians.

MFH: Because, I think, of the history that’s effaced through the misclassification of Anahit’s find-spot. The Hamidian massacres of the 1890s and the 1915 Armenian Genocide, executed by the Ottoman Empire, resulted in over 1.5 million deaths, but also displaced and dispossessed hundreds of thousands of Armenians from their ancestral lands. So, to erase the link between Anahit and her Armenian origins is a kind of structural re-enactment of the logics of cultural genocide invoked by Turkey and, as we saw very recently, by Azerbaijan.

Whatever the motivation for the 2012 repatriation campaign may have been, the discourse that emerged around that effort reveals the weight of the role that monuments play. The fact that it was conceivable for a monument fragment or a statue fragment to influence a parliamentary election tells us something. It tells us that cultural heritage serves as an axis around which collective cultural identity coheres, and it produces material effects in the political field.

PEK: So, cultural heritage—which is inclusive of monuments and markers, oral histories, music, food, and so on—really is an actor in creating communal and collective identities. Monuments in particular are these physical things that not only contain collective memories and narratives but also embody a community. Could you tell us a bit more about Azerbaijan’s cultural genocide campaign targeting indigenous Armenian monuments?

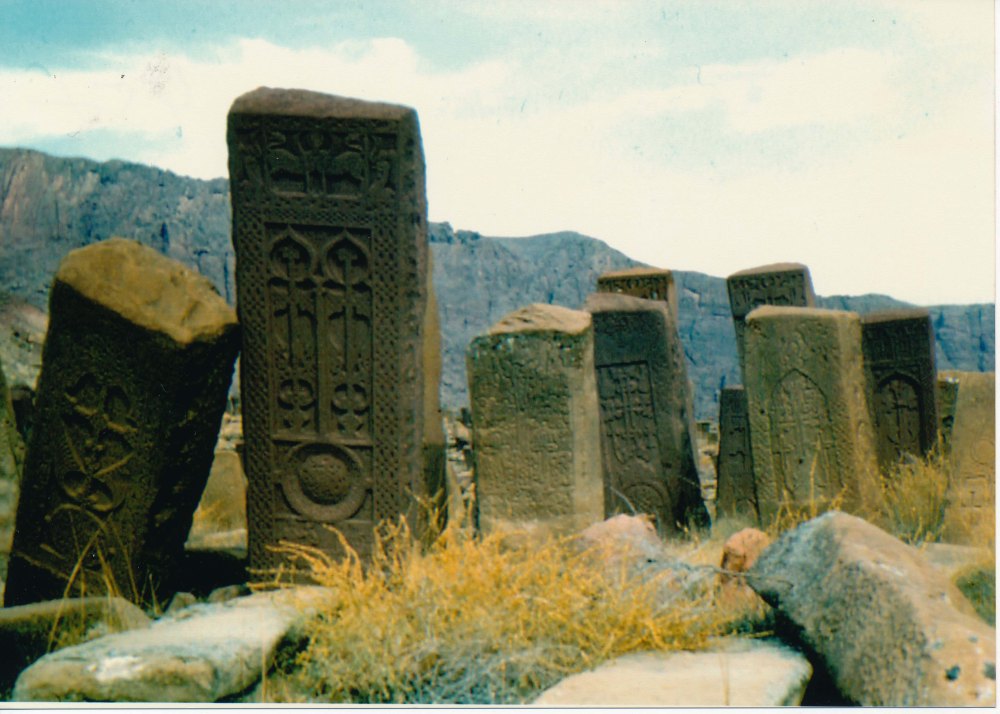

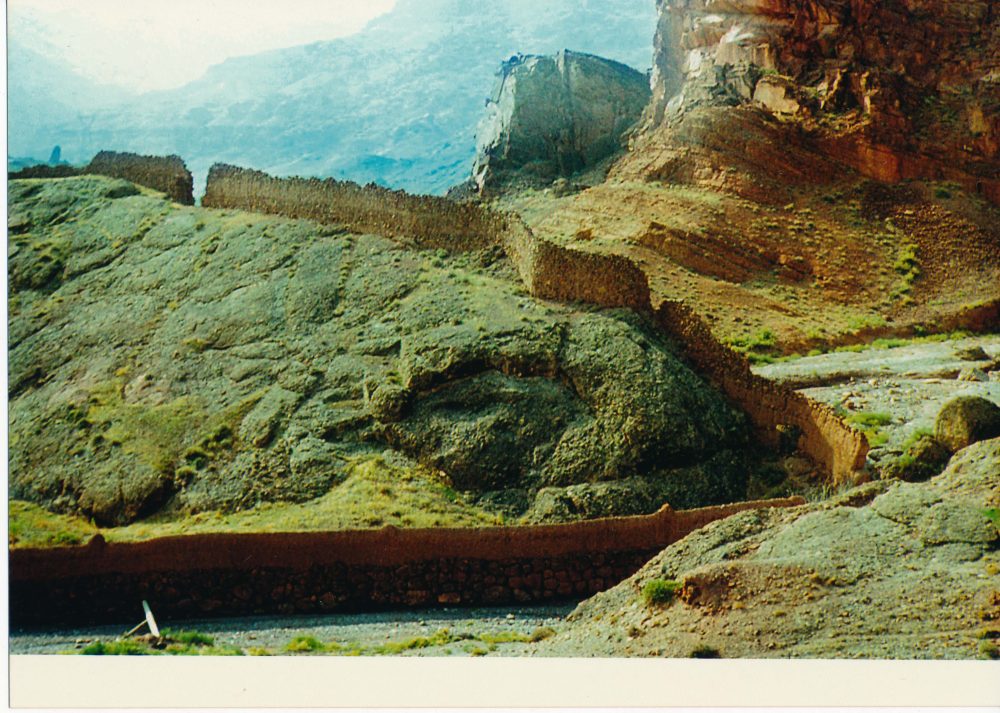

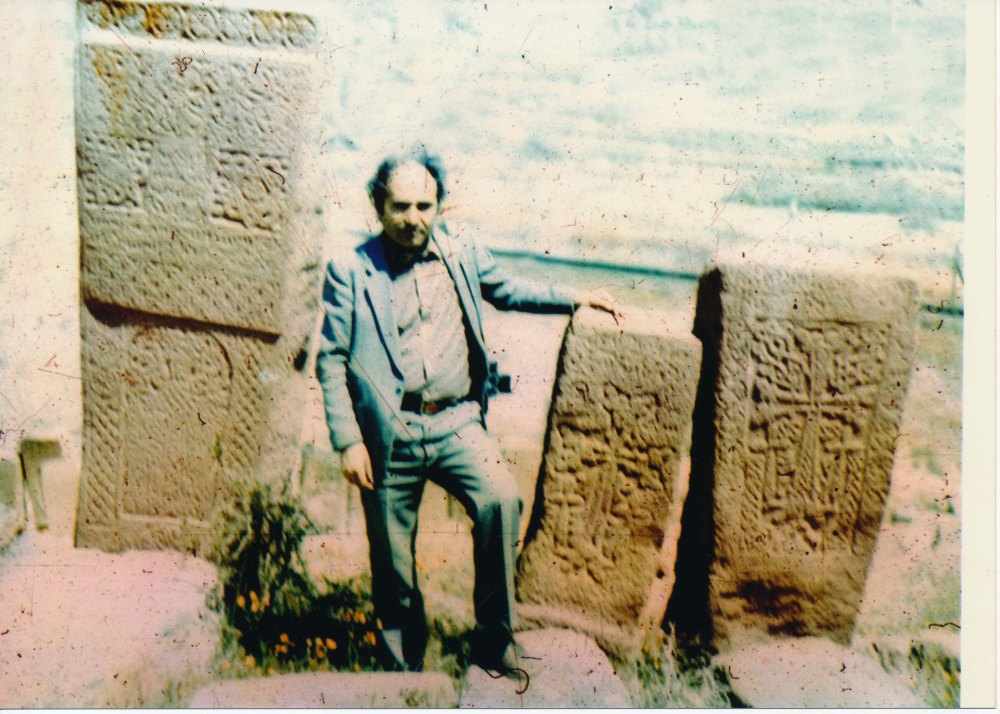

MFH: Azerbaijan’s systematic policy of cultural genocide has a long history. The Azerbaijani state fortifies its ethnoterritorial claim to the West Asian region of Artsakh by falsifying the region’s histories and performing Indigenous erasure, both materially and discursively. Its destruction of the world’s largest Armenian necropolis in the Azerbaijani-controlled exclave of Nakhchivan has been called the worst cultural genocide of the 21st century. And in 2019 the researchers Simon Maghakyan and Sarah Pickman published a forensic report in Hyperallergic on the cultural cleansing of indigenous Armenian monuments and artifacts in Nakhchivan. Their investigation revealed that 89 churches, 5,800 some-odd khachkars—Armenian cross stones—and 22,000 tombstones in the necropolis had been destroyed. But Azerbaijan categorically denies that this campaign of cultural genocide took place, because its officials say that these indigenous monuments could never have been there to begin with, since there were no Indigenous Armenians there at all.

Courtesy of the Argam Ayvazyan Digital Archive, a collection representing more than 25 years of Argam Ayvazyan’s efforts to document the Julfa cemetery.

PEK: You know, I also saw that report, and what’s so striking about that denial is that the destruction—the cultural genocide—is so visible to us. The aerial photographs from 2003 and 2009, for example, over where that medieval Armenian necropolis once was, just demonstrate how complete and thorough that destruction is. Do we know if any monuments and markers, or traces of Armenian existence linger in Nakhchivan, and if we do know, where are they now?

MFH: Because Azerbaijan refuses to allow independent fact-finding missions in Nakhchivan, it’s difficult to know anything with certainty. We know that in some cases the Armenian history of certain monuments has been redacted, and the monuments have been reclassified by the state. This [revision] was done with the 2009 unveiling of a mausoleum in Nakhchivan that originated as an Armenian shrine several centuries ago but is now classified by the state as an ancient Azerbaijani space. And according to Maghakyan and Pickman, roughly a dozen khachkars were removed from Nakhchivan before the destruction of the necropolis. One of these was displayed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Armenia! exhibition [2018―2019]. Traces of the monuments exist in the photographic archive of Argam Aivazian, who documented Armenian cultural heritage in the region from 1964 to 1987. And there’s also the Julfa Cemetery Digital Repatriation Project, which virtually recreates the destroyed necropolis in Nakhchivan. So, some monuments continue to exist virtually, others in our collective memory.

I think your work is instructive here, Tricia. In your essay for the Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, you outline a phenomenon that you call carceral heritage that I think is incredibly germane to this conversation. You define carceral heritage as “heritage that is physically and symbolically policed by historical powerholders, and as an act of process by which a community’s otherness and abjection are reinforced.”

Courtesy of the Argam Ayvazyan Digital Archive, a collection representing more than 25 years of Argam Ayvazyan’s efforts to document the Julfa cemetery.

Courtesy of the Argam Ayvazyan Digital Archive, a collection representing more than 25 years of Argam Ayvazyan’s efforts to document the Julfa cemetery.

PEK: Yes, I think you’re right. I first theorized carceral heritage, actually, as an analysis of a monument called The Statue of Peace, which was constructed by two South Korean artists who wanted to commemorate—and demand justice and reparations on behalf of—the hundreds of thousands of victims and survivors of Japanese imperial enslavement and sex-trafficking. And about 80% of those victims—or those who were kidnapped, essentially—are of Korean descent. But that article was informed by Black feminist scholars who have theorized the carceral state, particularly in the United States. And I was really struck by the ways that their thinking around the aesthetics of carcerality functions and operates in matters of cultural heritage of monuments. So, in other words, what I think is really germane to this discussion is that the visibility of censorship—that is, the redaction—has a particular kind of aesthetic role in the spectacle of violence against specific communities via the violence towards heritage and monuments. [All of] this is precisely the point of the state-sanctioned attacks on indigenous Armenian monuments. So, to summarize, I see this kind of violence towards heritage or monuments as operating through an aesthetics of carcerality by visibly demonstrating that an erasure has taken place, [which] actually leads me to my next question. This kind of state-sanctioned violence is ongoing, particularly now in the region of Artsakh. Could you tell us what’s happening right now, in Artsakh?

MFH: Well, the West Asian region of Artsakh has been home to indigenous Armenian communities since at least the second century BCE. This [past] is important to state explicitly, given Azerbaijan’s ongoing, programmatic efforts to redact the historical record, and to eradicate any trace of Artsakh’s Indigenous Armenian past. So, during Artsakh’s Sovietization, it was transferred over to the newly formed state of Azerbaijan despite the fact that its population was over 90% Armenian at the time, and it was then carved out as an autonomous oblast. Later, as the Soviet was dissolving, Artsakh’s Armenians fought a liberation war for self-governance and self-determination, and they’ve governed the enclave since 1994. Last year Azerbaijan launched a military offensive against Artsakh that resulted in thousands of deaths and displaced 100,000 Artsakhtsis. The offensive was launched with the direct participation of Turkey, a state that continues to deny the 1915 Armenian Genocide executed by the Ottoman Empire. After six weeks of continuous bombardment, Azerbaijan captured the city of Shushi, which was Artsakh’s cultural capital, and succeeded in capturing the ancestral Armenian lands through a trilateral agreement. Notably, after capturing Shushi, Azerbaijan reclassified it as the cultural capital of Azerbaijan. Today, Armenian prisoners of war and civilians remain captive in Azerbaijan. They are routinely subjected to beheadings, summary executions, and the desecration of their remains. The secretary general of the European Ombudsman Institute has called for their release, a group of Lithuanian cultural producers has called for their release, a bipartisan congressional resolution was just submitted calling for their release. They continue to be held captive by the Azerbaijani state in violation of international law. And at the same time, Armenian monuments and artifacts are facing the imminent threat of cultural genocide in Artsakh. When I spoke with Lusine Gasparyan, the director of Shushi Museums, for an article for Hyperallergic, she said “with the fate of Armenian POWs who are still being held uncertain, there can be little hope for the fate of our cultural heritage.”

Courtesy of the Argam Ayvazyan Digital Archive, a collection representing more than 25 years of Argam Ayvazyan’s efforts to document the Julfa cemetery.

PEK: Which monuments specifically have been targeted as a result of Azerbaijani state aggression in the past year?

MFH: The monuments most imperiled are those that bear Armenian script, because it’s those monuments that challenge Azerbaijan’s ethnoterritorial claims. In one particularly staggering maneuver of historical revisionism, Azerbaijan has manufactured a Caucasian Albanian historiography that insists on an unmediated link between Azerbaijanis and the now-vanished Caucasian Albanians who once also inhabited the disputed regions. So, this historiography emerged in the context of the Soviet Union and was championed by the Azerbaijani historian Ziya Bunyadov. And as Yelena Ambartsumian writes … tracing Azerbaijani lineage to the distinct Caucasian Albanians was a way for Azerbaijan to establish a national identity that was palatable to agents of state power in the Soviet, as well as a way to obfuscate the historical Armenian presence in the region. So, notably, Azerbaijan’s claims about its own Caucasian Albanian roots are directly contradicted by historical records and overwhelmingly disputed by non-Azerbaijani scholars. Today, Azerbaijan deploys Caucasian Albanian historiography as a tool of epistemic violence and a pretense for the desecration of monuments. State officials identify indigenous Armenian monuments as Albanian monuments that have been “Armenianized.” Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev has announced, without a shred of supporting evidence, that many historical documents confirm that Armenian historians and impostors have simply “Armenianized” the ancient Albanian churches. So monuments or sites that bear Armenian script and attest to Armenian indigeneity in the region will be marked for destruction.

PEK: And has there already been recorded destruction? How do we know [about] and account for destruction?

MFH: In November of last year, the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensics Research Lab released evidence of cultural destruction in occupied Artsakh. And that destruction included vandalism of the 19th–century Ghazanchetsots Cathedral, the desecration of a monument to Armenian soldiers fallen in the Artsakh liberation war of the 80s and 90s, and other acts of cultural destruction. Because they attest to indigenous Armenian histories in Artsakh, ancient monuments and cultural heritage sites materialize a decolonial gesture—decolonial insofar as they threaten the legitimacy and the ethnoterritorial claims of the Azerbaijani settler-state.

Courtesy of the Argam Ayvazyan Digital Archive, a collection representing more than 25 years of Argam Ayvazyan’s efforts to document the Julfa cemetery.

PEK: What’s really striking to me here, Mashinka, is that there’s recorded destruction—that there are aerial photos, there are eyewitness accounts, it seems. But I hear so little about this ongoing humanitarian crisis in the media today, especially here in New York City, where I’m speaking to you from. I wonder, to your knowledge, has the international community mobilized in support of Indigenous Armenians at all?

MFH: With very few exceptions, the situation in occupied Artsakh has been met with what I would call thunderous silence on the part of the international community and the global arts community. The Met issued a statement, in November, urging heritage protections and noting that the loss of cultural heritage sites would be a “grievous theft from future generations.” The Getty Trust also issued a statement noting that “deliberate physical attacks on cultural heritage are often figurative assaults on the people who identify with that heritage.” But these are, unfortunately, exceptions to the rule. And there’s also a well-documented history of Azerbaijan interfering with the operations of the press through illegal circuits of funding.

PEK: What about UNESCO? Have they said anything?

MFH: Well, not by happenstance, [laughs] Azerbaijan has provided funding to UNESCO in the sum of 5 million US dollars, and has also made payments—a payment of 468,000 thousand to the husband of UNESCO’s former Director General Irina Bokova. And it was under Bokova’s tenure that Leyla Aliyeva—daughter of vice president of Azerbaijan and President Ilham Aliyev—was named a UN goodwill ambassador. Interestingly, UNESCO has also hosted an exhibition titled Azerbaijan: Land of Tolerance at its headquarters. It bears noting this was after Azerbaijan’s acts of cultural genocide in Nakhchivan were revealed. The artist and researcher Nevdon Jamgochian illuminates these circuits of funding and Azerbaijan’s attempts to art-wash its dictatorial regime in his recent Hyperallergic report. So, to your question, UNESCO has remained notably silent. They’ve made efforts to send an independent delegation to inventory monuments and cultural artifacts in occupied Artsakh, but Azerbaijan has repeatedly blocked these efforts. UNESCO has responded by releasing a 327-word [laughs] press release. They’re now reportedly in the process of so-called high-level consultations surrounding the issue, but every day that passes without interventions is another day that centuries-old monuments are imperiled.

Kamee Abrahamian, Nancy Baker Cahill, Mashinka Hakopian, and Nelli Sargsyan, “Monument to the Autonomous Republic of Artsakh,” (2020), AR monument installed at Artsakh Avenue, Glendale, CA.

PEK: So, while these arts and cultural institutions, and states, are staying silent, artists and activists are leading the way. You and your collaborators are only some of these artists and activists who quickly mobilized to address the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Artsakh. You co-created the Monument to the Autonomous Republic of Artsakh, which is an augmented reality monument that lives on [the] 4th Wall app.

MFH: Yes.

PEK: [laughs] Can you talk about this?

MFH: [laughs] Yes, you’re absolutely right that artists have been taking a central role in responding to the crisis in Artsakh, and have been filling what has otherwise been a space of cacophonous silence on the issue. Some of these artists include the She Loves Collective, who I wrote about for ART PAPERS; and Kamee Abrahamian, who is one of my collaborators in the Artsakh Monument. And [Naré Mkrtchyan] … a filmmaker who went to Artsakh to document the situation; [and] Scout Tufankjian, a photographer who also traveled to Artsakh during the crisis to capture what was transpiring. As to our monument, Nancy Baker Cahill, whose incredible work focuses on virtual interventions in public space, very generously proposed that we collaborate on a project related to Artsakh. I’d already been in conversation with Kamee Abrahamian, the artist behind the #RECOGNIZEARTSAKH street art campaign that has cropped up worldwide, and which served as the visual basis for the AR monument. So I reached out to Kamee—and to Nelli Sargsyan, a remarkable scholar at Emerson, about contributing a soundscape for the work. The piece uses imagery from Kamee’s Recognize Artsakh campaign, which takes its inspiration from Armenian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov’s classic The Color of Pomegranates. And the monument bears the text “Artsakh Endures.” It’s geolocated on Artsakh Avenue in Glendale, a city that’s home to one of the largest Armenian diasporic communities in the world. And the impetus for the monument, I think, aligns very closely with your description of monuments for the most recent issue of ART PAPERS, particularly the section where you write that “monuments embody collective identities, as they articulate a set of ideas, values, and truths. Sarah Ahmed instructs us that power works as a mode of directionality, and that things orient our bodies towards certain futures.” So, given the events of the last five months, it often seemed, and seems, impossible to construct a political imaginary around a future for Artsakh. I think that impossibility is precisely what those who have seized power in Artsakh want to cement—a settler futurity that’s exterminated all remnants of indigenous Armenian life and life-worlds. So, to counter the foreclosure of those political imaginaries, our AR monument orients viewers toward the imaginary of a future in which Artsakh remains visible, a future in which Artsakh endures.

Kamee Abrahamian, Nancy Baker Cahill, Mashinka Hakopian, and Nelli Sargsyan, “Monument to the Autonomous Republic of Artsakh,” (2020), AR monument installed at Artsakh Avenue, Glendale, CA.

PEK: I think what’s really interesting about Artsakh Monument is that, first, it reminds me a lot of In Plain Sight, which took place, I think, in southern California. Artists sky-typed—and I believe, actually, some of them did so through the same app, [the] 4th Wall app—they sky-typed messages of solidarity and support of migrants who are interned and incarcerated in US detention centers, and what’s so striking about your monument and In Plain Sight is the way in which you are taking up monumental aerial space as an aesthetic strategy that might bring about attention—public attention—and also provoke a different kind of, let’s say, affective response, to these different human rights violations that are occurring across the world. But I wonder if you could please describe [the] 4th Wall app. Who’s it for, and what are the monumental interventions that this app is trying to make?

MFH: 4th Wall app is the brilliant project of Nancy Baker Cahill, and it was founded in 2018 as a free augmented reality public art platform that focuses on resistant projects, and that expands the definitional boundaries of public art and … the possible modes of experiencing public art.

PEK: This is really interesting, because augmented reality is a relatively new medium for claiming and documenting a community’s presence. And despite its relative newness, I do know of a lot of artists and activists and educators who are working with it, and mobilizing it as a tool towards justice, and as a tool to think about how art and justice can inform each other. I’m thinking of Glenn Cantave’s Movers and Shakers NYC; Cheyenne Concepcion, based in San Francisco; and Ada Pinkston, who is currently creating an AR monument in Los Angeles. But, of course, a lot of the kind of, let’s say, visual documentation with regard to indigenous Armenian monuments has been historically done—executed—by other means. I’m thinking about Argam Aivazian, who you mentioned earlier, who dedicated much of his scholarly life to bearing witness to the traces of Indigenous Armenian life across Nakhchivan, in particular. So, we know that Aivazian didn’t use AR, but he used photography. So, I wonder in what ways does your work in or about Artsakh inherit or respond to the work of researchers like Aivazian—or, you mentioned Scout Tufankjian … who went to Artsakh to document what was happening on the ground.

MFH: That’s a fantastic question. I think that there’s something incredibly generative in AR that enables practices that previously required a tremendous volume of resources, and … the approval or the sanctioning of the state. And what AR allows for is the production of new forms of monumental practice that are unauthorized, unsanctioned, and bottom-up rather than top-down. And, like you, I’m very hopeful about the kinds of aesthetic interventions that can emerge in that space. As to Aivazian—Aivazian’s work, as you note, was devoted to preserving cultural histories that faced the threat of erasure. And that threat of erasure looms larger now in occupied Artsakh than perhaps ever before. Preserving indigenous Armenian histories and the cultural narratives of diasporic dispersion and displacement is at the core of much of my own work, and the work being done by other diasporan cultural producers around the globe. I’m currently co-curating an [exhibition] that deals with that thematic for Reflectspace, a gallery in Glendale, with Anahid Oshagan and Ara Oshagan. The virtual exhibition, which will launch in April, is going to foreground Armenian diasporan artists’ responses to the crisis in Artsakh, and to the ongoing crisis that confronts indigenous Armenian monuments and cultural heritage there.

PEK: I’m really inspired by your understanding—or, rather, your explanation—of the potential of augmented reality, especially as a diasporan cultural producer, when you cannot physically be in that place that you have explicit heritage links with. I also think what’s really powerful about what you’re saying is that, in lieu of being able to go to that place—to your ancestral home—you can bear witness, and you can claim that connection to that place through this new mode of technology in a way that expands different possibilities, or that allows for people to imagine embodying and occupying that space, if you will. I do have a question about [the] 4th Wall app. How does it work, exactly, and how can people who want to engage with your monument—Artsakh Monument—do so?

MFH: [The] 4th Wall app is free to download, and it collects no data. In order to experience a work that’s hosted by [the] 4th Wall app, you need to visit the site where the work is geolocated. So, in the case of our monument, it’s geolocated at the corner of Artsakh Avenue and Broadway, in Glendale, CA. And viewers need to be on site with the app loaded for the monument to appear. It’s crucial to note, given that this is a monument to indigenous Armenian self-determination, that the site is situated in the unceded, ancestral lands of the Gabrielino/Tongva peoples. And this [history] is something we were acutely aware of, that our monument to indigenous Armenian self-determination is virtually sited on indigenous lands where we ourselves are uninvited guests.

PEK: Those were all of my questions. This was such a productive conversation for me. I learned so much, Mashinka. Do you have anything else that you want to add?

MFH: Only that I am enormously grateful for the work you are doing in this space, for your work on carceral heritage, and for the labor that you’ve undertaken in bringing the role and the weight of monuments here in the US, and globally, to light.

PEK: Oh, thank you.

***

Research for this conversation has been made possible by a grant from the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU).

Many of the images in this conversation are courtesy of the Argam Ayvazyan Digital Archive, a collection representing more than 25 years of Argam Ayvazyan’s efforts to document the Julfa cemetery. It is important to note that the Argam Ayvazyan collection includes photographs taken by Aram Vruyr and others. It also contains images of the destruction of Julfa cemetery by soldiers in 2006, taken by an Armenian Bishop from the Iranian side of the Arax river.

Mashinka Firunts Hakopian is a writer, artist, and PhD candidate in the history of art at the University of Pennsylvania. She lives in Los Angeles, where she teaches in the Department of English at UCLA. She is a founding member of the performance group Research Service alongside Avi Alpert and Danny Snelson, with whom she has presented projects for the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, and The Drawing Center in New York. She is a contributing editor to ASAP/J, and her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Art in America, Los Angeles Review of Books, Performance Research, Cinema Journal, and elsewhere.

Patricia Eunji Kim PhD is an art historian, curator, and educator based in New York City. She is assistant professor/faculty fellow at New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study, associate director of public programs at Monument Lab, and editor of the Monument Lab Bulletin. She is writing the first book on the art and archaeology of royal women from the Hellenistic world, and is co-editor of Timescales: Thinking Across Ecological Temporalities (University of Minnesota Press, 2021) and Shaping the Past (Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, under contract).