Monumental Futures

Wangechi Mutu, The Seated I – IV, installation view, 2019 [photo: Bruce Schwarz; courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels]

Share:

Monuments—as heritage, artifact, or art—constitute an extension of state power, similar to public school curricula or privatized prisons. Symbols, when produced, protected, co-opted, or propagated by the state, still exist and function beyond state control: They are permeated by the philosophical underpinnings of a culture’s values and the aspirations of its people. Traditionally, when Americans pledge allegiance to the United States flag we remove our hats and hold our hands over our hearts to pay respect to this symbol of national strength and pride. Yet when civil unrest erupts in the streets, the flag becomes its own battleground: waved boldly by the radically conservative and liberal alike. Flown inverted—according to military protocol—the flag can be used to signal life or property in dire distress. Unarmed protestors have controversially co-opted this action in efforts to protect themselves against militarized police.

Activist Bree Newsome takes down Confederate Flag at South Carolina Statehouse (screenshot), 2015 [courtesy of Vox and Youtube]

Filmmaker and activist Bree Newsome’s iconic 2015 act of civil disobedience—in which she scaled a 30-foot flagpole to remove a Confederate flag that was regularly flown outside South Carolina’s State House—revealed the precarious power of symbols. Threatened by police below her, Newsome gathered the flag in her fist and shouted, “I come against you in the name of God. This flag comes down today.” She risked her safety and freedom in an attempt to sever the bonds between Lost Cause Ideology and contemporary state power. This symbol of the Confederacy, pregnant with myth, was brought down by the hands of a Black woman and revealed for what it really is: nylon. A stretch of nylon held together by wisps of negationist histories and overt white supremacy. She was quickly arrested and charged with defacing a monument. Newsome’s act blurred the line between protest and performance. Although the Confederate flag was replaced within 60 minutes, this event reverberates through our culture as an act of defiance and an assertion of power. It was monumental.

Now, as contemporary art discourse and activist initiatives of removal intersect within the public landscape of monuments, we must consider their symbolism and how it can be used to empower or oppress. In Toward a Monumental Black Body—published in ART PAPERS’ Spring 2020 issue—I drew upon personal experiences to ponder whether figurative depictions of Black people in monumental form could ever escape centuries of objectification of Black people’s bodies or racist depictions in visual culture. Faced with empty plinths and pedestals, an often-distasteful American response is to instrumentalize a famous Black person in hopes of filling these absences. This process often involves mobilizing the person’s likeness and accomplishments, placing the burden to perform anti-racism squarely onto that Black body, with minimum impact upon the state’s unchanged agenda. New York’s Central Park monument to Dr. J. Marion Sims was removed in 2018 and is soon to be replaced with a sculpture honoring Vinnie Bagwell. Bagwell’s monument will depict an angel in the form of a Black woman, dressed in a skirt adorned with sculpted faces of various other Black women. As impactful as Bagwell’s monument may be, it does not absolve the damage Sims did to Anarcha, Lucy, Betsey, Henrietta, Laure, and the countless other victims of his torturous procedures. The city of New York is not absolved, after relocating Sims’ monument safely to Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. The exchange of figures does nothing to address the medical racism that living Black women still experience. The bodies of Black people cannot function as a bandage to cover the festering wounds of white supremacy, nor as a salve to placate Black anger and pain.

Activist Bree Newsome takes down Confederate Flag at South Carolina Statehouse (screenshot), 2015 [courtesy of Vox and Youtube]

Unfortunately for us all, replacing the statue of an enslaver, a rapist, a murderer, or a nation-traitor with one of Harriet Tubman will not solve the race problem. As Newsome’s act of civil disobedience revealed, we need more than acknowledgment; we need action. We need more than sentiment; we need power. We are witnessing a shift in the place and purpose of monuments, championed by the united efforts of activists and artists. Activists are claiming agency over their shared public spaces by contesting, defacing, and removing symbols that no longer serve their communities. Contemporary artists are producing powerful and innovative public artworks that illuminate suppressed histories and reclaim power over the narratives told in public spaces. By working outside the channels of production and approval of government-sanctioned monuments, artists can explore and expand what is understood as a monument, transcending traditional forms, materials, and symbolism. These interventions by artists not only critique traditional monument-making practices but propose a future for monuments to function for all people.

The Washington Monument, Washington, DC [photo by David Bjorgen courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

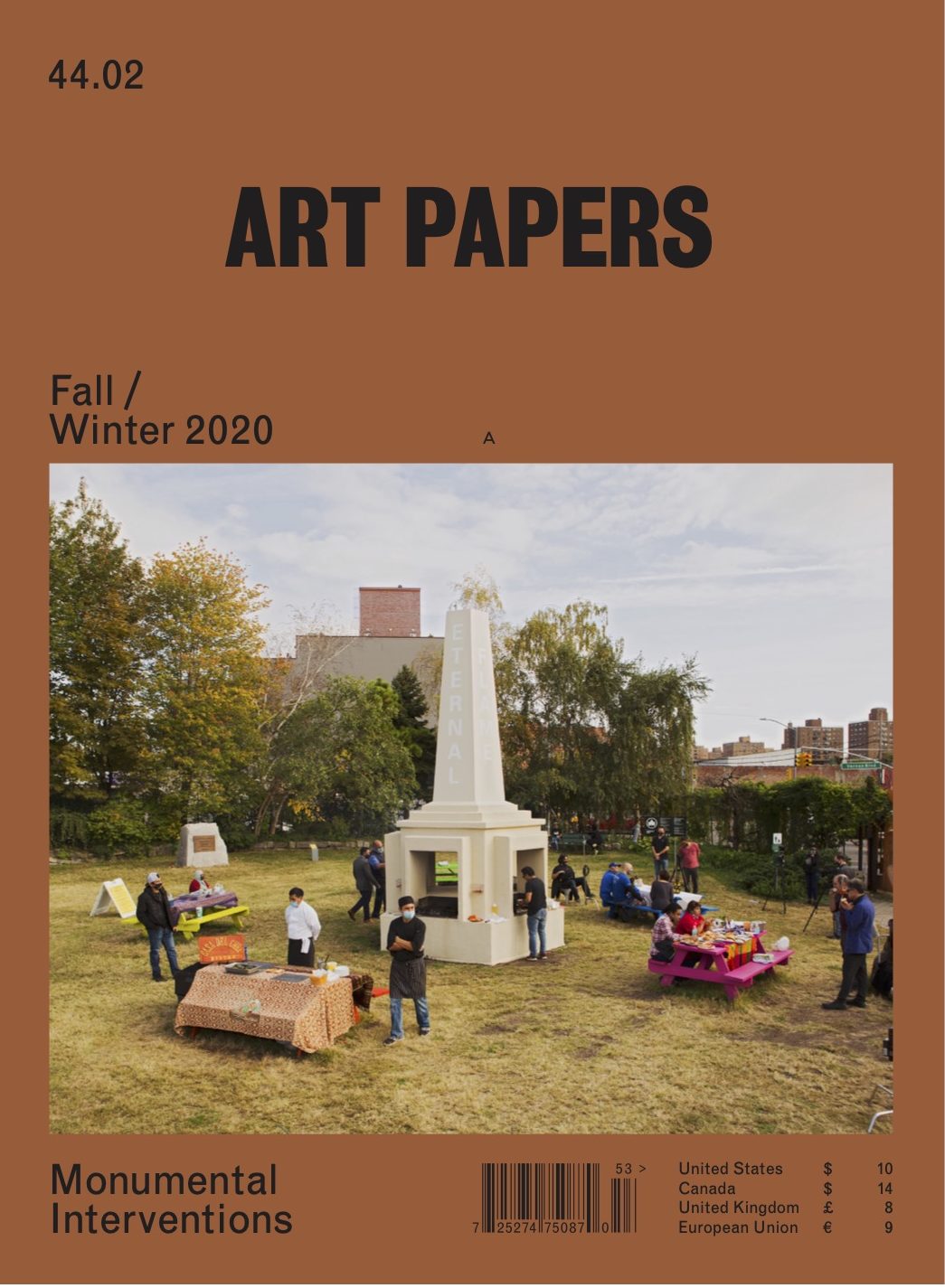

Within the American monument tradition, visual and architectural references to Sumer, Egypt, Greece, and Rome form the foundation of governmental visual culture. These references have allowed us to imbue American figures, such as George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Confederate generals, with symbolic power of the ancient world. Consider the obelisk form of the Washington Monument, the Doric columns that support the Lincoln Memorial, and the equestrian form of J.E.B. Stuart’s statue on Monument Avenue. By subverting, appropriating, co-opting, and outright rejecting conventional monument-making traditions, contemporary artists are making significant interventions into this history. Traditional monuments articulate their power from their seemingly permanent structures and endurance over time. Whether thanks to the slow process of litigation, the swift collective might of protestors, or the vengeful winds of Hurricane Laura, however, no structure is permanent. Contemporary artists are also exploring alternatives to permanence by creating monumental public artworks built with the intention that they shall change, adapt to new contexts, or be removed when they no longer serve the people. One of the most powerful and performative aspects of American artist Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War is its revelation to the world that, regardless of scale and material, monuments can move, from city to city, and from context to context.

Although Toward a Monumental Black Body critiques Wiley’s Rumors of War for referencing traditional Western monument aesthetics, the sculpture does make an art historical intervention into canonical depictions of Black bodies on the American landscape. A Black man, cast in bronze at magnificent scale with locked hair and Nike shoes, remains an iconoclastic image in American visual culture. Rumors of War is one of several recent high-profile monumental interventions made by contemporary artists. Another is Kara Walker’s Fons Americanus (2018), commissioned by the Tate Modern in London. This artwork is modeled after the Victoria Memorial near Buckingham Palace, which was commissioned after the queen’s death to commemorate her 63-year reign over the British Empire. Like Wiley, Walker references a traditional Western monument form and canonical works of art history to form her fountain. Walker, however, is successful in subverting the form to contest and ultimately undermine the tradition of triumphalist monuments to empire. Fons Americanus is a sprawling, multitiered fountain installation constructed of recyclable cork, wood, and metal. The work depicts narratives of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, using water—as a means of transport and escape—to represent power. Walker presents a series of alternative historical narratives, symbolism, and mythologies that, when placed in conversation with the Victoria Memorial, create a truer depiction of the cost of empire.

Wangechi Mutu’s four monumental bronze figures, collectively titled The NewOnes, will free Us (2019), were commissioned to fill empty niches in the historic façade of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Individually titled The Seated I, II, III, and IV, the works are representational sculptures of Black women who appear simultaneously human and alien. Their elongated necks and oblong heads evoke an otherworldly futurity, while Mutu’s use of African sculptural aesthetics evokes the ancient. Mutu enlivened their metallic skin by using patina processes and dressed them in thick coils that wrap around their bodies like protective armor. Referencing East African lip plates, they are adorned with round mirrors that redirect sunlight. Mutu created The NewOnes, will free Us within the sculptural tradition of caryatids, a historic African art form that uses representations of women’s bodies to bear the weight of a structure. Mutu’s “caryatids” defiantly reject the weight of the Met’s facade—and ultimately that of the sculptural tradition—with their stolid and attentive postures. Instead of bearing weight, they sit high on stone pedestals and gaze beyond onlookers. Their power is innate, conveying a rejection of objectification and permanence. Now that they have been deinstalled from the Met’s façade, Mutu’s sculptures will find new homes—perhaps in private or museum collections—and, in those future contexts, generate different articulations of defiance.

Wangechi Mutu, The Seated I – IV, installation view, 2019 [photo: Bruce Schwarz; courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels]

Simone Leigh blends West African sculpting traditions and Black American iconography to create a unique visual language that expresses Black femininity and power. Steeped in this radical visual mode, Leigh abstracts the figure into expressive forms of utility to depict Black women’s bodies as crafted vessels. Her clay sculptures incorporate crude forms of the built environment such as thatches of raffia, corrugated Quonset huts, or corroded piping blended into feminine forms. The heads, shoulders, and upper torsos of her figures cannot be separated from jug, calabash, or cast iron pot. Leigh provides an alternative to classical Western renderings of the body that have been used to other, objectify, or erase Black women. Leigh’s sculptures materialize knowledge and trauma held in Black women’s bodies. Her sculptures lack eyes, signifying that they are not representations of individuals but an embodiment of Black women’s consciousness. Brick House (2019) is a large-scale public sculpture commissioned for New York’s High Line Plinth. The 16-foot-tall sculpture towers over onlookers to evoke a sense of self-determination and inaccessibility. Leigh has stated that Black women are the intended audience for her work, making Brick House one of the few structures in the American landscape that is by and for Black women. Brick House contrasts the cityscape, appearing like a fortress, a totem for self-sufficiency, endurance, and self-love.

Simone Leigh, Brick House, 2019, a High Line Plinth commission, on view 2019 – Spring 2021 [photo by Timothy Schenck; courtesy the High Line]

Hank Willis Thomas, All Power to All People, Washington D.C., 2020 [photo by Avi Gupta, courtesy of the artists and Human Rights Campaign]

Hank Willis Thomas rendered a classic afro pick at monumental scale to articulate its enduring symbolic power and cultural significance. Thomas’ 28-foot-tall, 7,000-pound sculpture, All Power to All People (2020), exemplifies the notion of monumental intervention through its insertion into multiple public spaces in Philadelphia, followed by a tour of various cities across the US. Thomas elevates Black material culture by placing the comb in direct conversation with other monumental objects on public display, such as the Liberty Bell. Philadelphia’s iconic bell represents liberation and independence for the United States. Similarly, the afro pick has become emblematic of liberation and independence for Black people throughout the African diaspora. Popularized in the 1970s, the “Black Fist” afro pick represents a convergence of the Civil Rights, Black Power, and Black is Beautiful movements. Designed for use on afro-textured hair, it also represents the rejection of Eurocentric beauty standards and empowerment through self-love. The afro pick features a single closed fist emerging as its grip, which gestures to every strong fist raised in solidarity with Black liberation. Different iterations of Thomas’ sculpture have been acquired by art institutions, displayed on the grounds of Philadelphia’s city hall, and installed in a North Philadelphia community garden. Thomas’ work asserts that power lies in the people’s hands, and that liberation of one people has the potential to liberate all. All Power to All People functions much like Newsome’s act of civil disobedience: to remind us of our individual and collective agency. The power to incite change is held in our own closed fists.

Public monuments are currently being contested, recontextualized, and removed from public space almost daily. These removals threaten the stability of the ideologies such monuments represent and leave a landscape tense with absence. In addition to political and economic uncertainties caused by the recent presidential election and a persistent global pandemic, we must also confront the empty plinth and pedestal. Schools and city streets have lost their names, football teams go without mascots, and communities face empty public squares. Many people are living in a state of agitation; when it is unclear where the power lies, anxieties can be exacerbated. Americans are struggling with an existential crisis, one that calls upon us to redefine who we are and who we aspire to be. This new and fervent energy directed toward the public landscape reveals a nation poised for unprecedented change.

Lincoln Memorial, East Side, 2013 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

Wangechi Mutu, The Seated I – IV, installation view, 2019

A dossier highlighting the work of seven artists was originally published alongside this text as part of ART PAPERS Fall/Winter 2020. The featured artists, who are in various stages of their careers and hailing from multiple nations, have interrogated and intervened upon the symbolic and formal language of monuments. Monumental Interventions presents possibilities for a radical reformation of monument traditions. These artists, in concert with many others, have fought—and continue the fight—to transform their public spaces by uncovering suppressed histories, resisting oppression, and telling formerly silenced truths.

***

This feature originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Fall/Winter 2020 // Monumental Interventions.

TK Smith is a Philadelphia-based writer, art critic, and curator. He is currently a PhD candidate in History of American Civilization at the University of Delaware, where he researches art, material culture, and the built environment.