Toward a Monumental Black Body

Dex’s Tennis Shoes on Telephone Wire, Corner of Lawton St. and Westview Dr., 2020 [photo: TK Smith]

Share:

Visceral debates about the place and purpose of monuments in the United States reveal the power and perseverance of our grand historical narratives. Grand—or “master”—narratives constitute a method of teaching and legitimizing historical knowledge through storytelling. They create a linear view of history that often erases the experiences of marginalized people to create a plausible narrative in alignment with contemporary political aims. However true or false these narratives may be, monuments are built to grant them physicality and spread selective knowledge throughout public space. Monuments function as totems whose inclusion and exclusion of particular histories shape a narrative of national identity by which citizens are measured. Within the context of the United States, rising numbers of people are pushing against monuments that embody the ideology of grand narratives and demanding new monuments that reflect more diverse narratives, ones closer to contemporary ideals of subjective truth. Artists and activists are working to uncover suppressed histories, commemorate the marginalized, and (attempt to) address wounds of the past by creating large-scale public artworks whose aim is to reshape the American landscape.1

Teddy Bears, Ribbons, and Balloons for an Unnamed Woman, North Ave. and Joseph E. Lowry Blvd., 2020 [photo: TK Smith]

To critically study American monuments, one must interrogate the relationships among power, the built environment, and individual positionality. Monuments function as manifestations of power—the economic, cultural, and ultimately hegemonic power of the state. They are then constructed, maintained, protected, and destroyed at the discretion of the state. The grand narratives that monuments are built to embody are viewed through the lens of those who hold the most collective power. Placed in public space, the structures appear deceptively democratic. Public space consists of the natural and artificial spaces intended to be accessible to all citizens. It is where citizens are meant to express their Constitutional rights to protest and assemble. If you are a citizen of the United States and have full access to the rights and privileges of that citizenship, there is no danger in public space. If your current positionality includes a marginalized identity, your safety in public space and relation to the built environment begin to shift. The concept of positionality understands that one’s engagement with the world at any given moment is shaped by various interconnected constructions of identity. Race, gender, class, and sexuality are just a few of the lenses that affect how a person processes and responds to knowledge. Thus is it true of how people experience monuments, as monuments constitute one way our bodies interact with state power.

I disassociate from my physical body often. I have come to conceptualize my body as something I carry around, not as something that carries me. I understand my body as an object that I use to navigate and interrupt space. My body is large, my body is male, and my body is Black. It is a political object that I can weaponize. I can roll my shoulders back and walk down the street, daring someone to collide with me. I can deploy my body in a certain space to be subversive or humorous. Imagine me, a large Black man, getting trapped in a plastic slide on a public playground while attempting to find some joy. I can dress my body up, sag my pants, or let my kinky hair grow wild, fully understanding that these actions have direct correlations with my viability for survival.

The contested status and legal protection of Confederate monuments in the United States brings to the forefront Black Americans’ relationship to the built environment and the state. Throughout the century following the US Civil War, Confederate Monuments were erected across the country to memorialize the soldiers and sailors of the Southern Rebellion. Confederate monuments glorify support for the institution of slavery and memorialize a war for which Black Americans fought and died—on both sides—with their freedom at stake. Generations of Americans have built their personal, familial, and national identities on the narratives perpetuated by such monuments. As a result, challenges to such monuments’ existence is perceived as an existential threat to some Americans’ sense of their place in history. Although few Confederate monuments feature figurative representations of Black people, they have come to represent the fragility of Black citizenship, a lack of economic and political power, and the various means and methods of White supremacy. Black Americans are forced to measure their citizenship against a built environment that is informed by the legacy of chattel slavery, structural socioeconomic inequity, and the erasure of their labor and cultural contributions.

Lelo Jones’ Ink Tribute to Ida B, an African Queen, Left Forearm, 2020 [photo: TK Smith]

Within the visual history of the United States are innumerable examples of how the bodies of Black people have been objectified and used as political objects to assert social hierarchies and exercise control. In public space, lynchings appropriated the abuse and mutilation of a Black body for spectacle to inspire terror and compliance. Lynched bodies became sites for White Americans to enjoy picnics and fireworks—as have Confederate monuments. The victims’ bodies—hung, beaten, or burned—were routinely left to be discovered by their community and buried without justice or vindication from the law. This practice’s history and its victims have been memorialized by the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, AL. The memorial abstractly references the known totality of individuals lynched through 805 hanging slabs of steel, etched with the locations and names of those victims. The memorial features thousands of recorded accounts of racially motivated lynchings that date from 1877 to 1950. The sculptures that surround the monument are representationally figurative, and they depict narratives of Black bodies enslaved, in pain, in fear, or in resistance to oppression. They are in dialogue with many other sculptures and monuments in American public space that depict Black people through the lens of unrealized citizenship.

Beyond the physical landscape, depictions of Black people in pain and duress are a staple of American visual culture. One could reference the daguerreotypes commissioned by Louis Agassiz in the mid 19th century to serve as scientific evidence of racial difference and white superiority. The series depicts seven enslaved men and women in front and side views, their bare bodies exposed to the lens. The subjects’ listless gazes reveal the extreme vulnerability of their social status, as well as the physical and mental scars of chattel slavery. The photographic documentation of Emmett Till’s lynched body was widely circulated to coerce sympathy for the Black plight and to inspire social change. The image of his body, brutalized beyond recognizable form, had more cultural impact than any words spoken or written against lynching. Even in the realm of fiction, the now canonical work of contemporary artist Kara Walker relies on narratives of the Antebellum South to depict violence enacted on Black bodies. Her silhouette works unabashedly continue a violent narrative of physical and sexual abuse, one which can then be sold and hung in people’s homes. The tradition of widely circulating images—and now videos—of violence against Black bodies creates a culture of desensitization to Black pain. What do you do when you see footage of a Black person being shot on your cell phone screen?

Heroes Don’t Wear Capes, Kaepernick as the Martyr St. Sebastian by @occasionalsuperstar, Corner of Peeples St. and Ralph D Abernathy Blvd., 2020 [photo: TK Smith]

After Michael Brown was shot in Ferguson, MO, they told me he lay in the street for four hours. For four hours his body lay in the street. In response, I laid my body in the street. Four minutes pales in comparison to four hours. When we marched in Ferguson, when we blocked traffic on Interstate 44, when I lied to my mother about protesting at night, I was exercising autonomy. I exercised my autonomy in that moment to use my body as a political object. Michael Brown did not. I remember marching along Market Street, holding the hands of two people I love, shouting out, “No justice, no peace.” Our voices rang through downtown St. Louis and echoed back at us. Our peaceful protest was planned. The city had blocked off streets and stopped traffic to corral our marching along a predetermined path. Businesses were locked up and no pedestrians strayed onto the streets. Behind metal gates, heavily armed police officers watched us with little interest. I can’t articulate the deep sadness I felt while marching through empty city streets and listening to the sound of my own voice echo back at me, “Black lives matter.”

Deeply embedded images of violence against the Black body within American visual culture meet a stark contradiction when the Black body is rendered in triumphant, monumental form. A positionality that is shaped by inhabiting a Black body in the United States becomes fragmented by such pedagogical illustrations of citizenship—ones that teach us who is worthy of full rights and who is not. Monuments function as one expression of power—the same power that is then supported by a web of other expressions, such as the vast inequities of the education, penal, and political systems. Several incidents in the last decade forced the nation to once again contend with the devaluation of Black life. The 2014 death of 12-year-old Tamir Rice, the 2015 death of Sandra Bland, and the 2015 Charleston Church shootings exemplify instances of shock that clarified the relationship of the Black body to the state. The Black Lives Matter movement is an international effort, created out of a necessity to assert the radical belief that the lives of Black people matter. So, of what real value is a public monument to a Black person living in a nation where inanimate objects commemorating the institution of slavery have more legal protection than a child?

Artists—specifically artists of color—are creating artworks that open an imaginative space in which to interrogate what a monument for commemorating the lives of Black Americans could be: ones that do not visualize Black pain or acquiesce to state power. Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War infiltrates the sculptural tradition of European war monuments with the body of a Black man. The sculpture was first unveiled in New York City’s Times Square. It has since moved to its permanent home on the grounds of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, VA. The museum’s campus is adjacent to Monument Avenue, where the former capitol of the Confederate States of America has decorated a series of intersections with monuments to memorialize such Confederates as Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

Lonnie Hood, Rest in Peace, by @MrVitaminD, Corner of Lawton St. and Westview Dr., 2020 [photo: TK Smith]

Wiley’s large-scale bronze sculpture stands 27 feet tall and 16 feet wide, including its limestone base. It depicts a male figure mounted on a horse, his body turned slightly to display his proud, lifted chest and an over-the-shoulder gaze. Modeled after the 1907 statue of Confederate general J.E.B. Stuart found on Monument Avenue, Rumors of War imitates the original sculpture’s mastery of equestrianism, movement, and tension. The figure grips the reins with a single hand. The other hand holds the back of the saddle, emphasizing the twist in the figure’s torso. The horse’s right hoof is raised as it rears, as if to a halt. Rumors of War references a historical sculptural language often denied to the figuration of Black Americans and thereby intervenes into the way we see and understand such structures in relation to ourselves.

Wiley is well known for embedding Black bodies within Eurocentric styles. His large-scale, classical oil paintings encourage viewers to interrogate Black representation and the Black body’s relation to hegemonic power. By adopting the sculptural language of the equestrian statue in his monumental artwork, Wiley makes evident that its purpose is as a political object. His figure is now in visual conversation with the sculpture of Louis XIV at the Louvre, and George Washington in Washington Circle. Where we would traditionally see the body of a White conqueror or general, there sits a Black man. Wiley sculpted the figure using an amalgamation of features from several subjects, creating a symbolic figure to represent all Black men—a reference to the trope of the Unknown Soldier—to represent many unidentified men lost in battle. Wiley presents a man who appears to have no military or political rank, no royal blood or divine inheritance, and places him on a horse. An otherwise anonymous Black man is thereby placed within a sculptural language of power and significance constructed and perpetuated by the dominant culture. If Wiley’s gesture is jarring, or if audiences are made uncomfortable, such an outcome reflects the scarcity of representation within historical narratives afforded Black Americans beyond those of slavery and oppression, particularly within narratives of the Civil War.

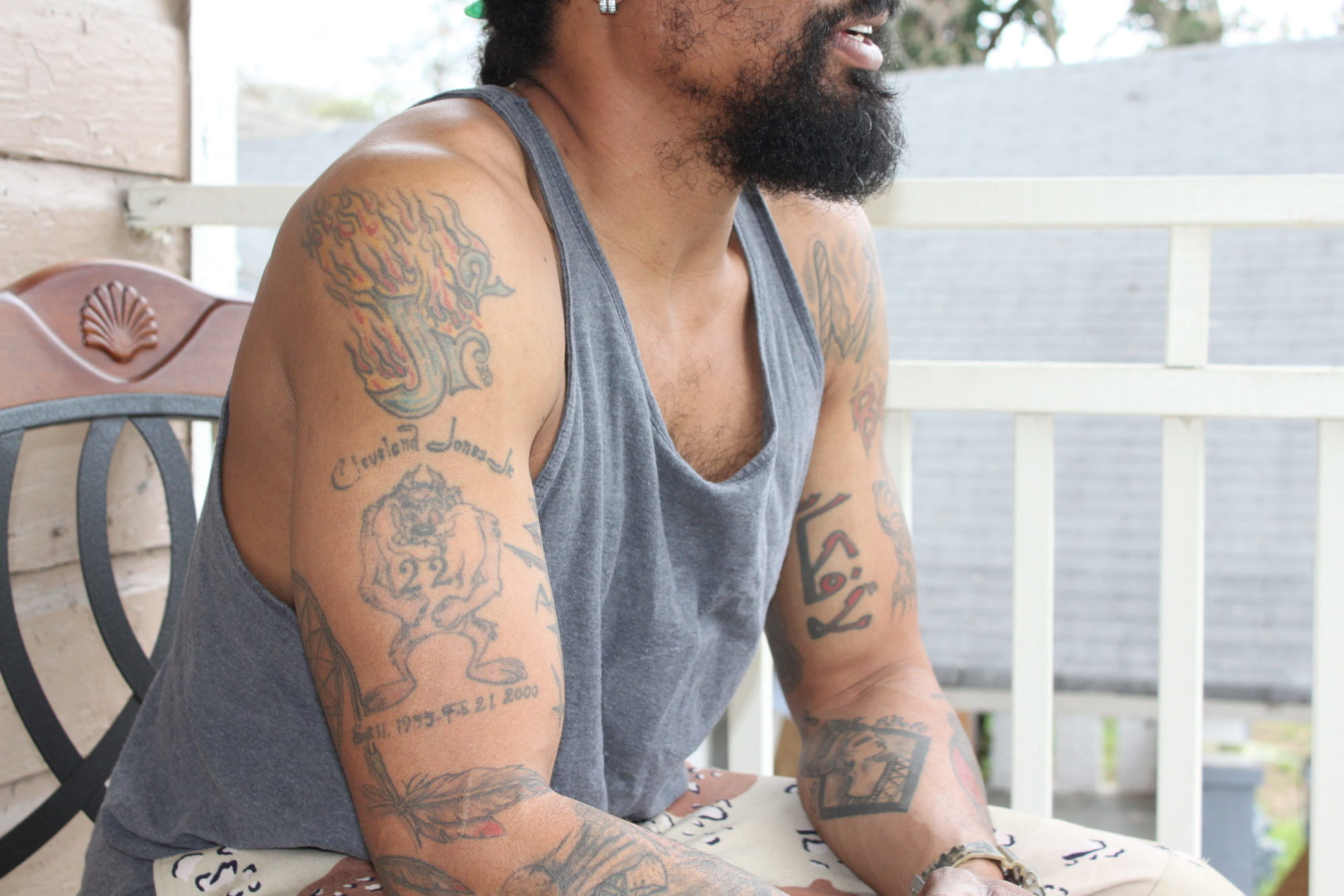

Lelo Jones’ Ink Tribute to Cleveland Jones Jr., a Tasmanian Devil on the Field, Right Bicep, 2020 [photo: TK Smith]

Rumors of War stands in proximity to the Arthur Ashe Jr. monument on Monument Avenue in Richmond. The placement and purpose of this 1996 bronze sculpture of the famed Black American tennis player has been a point of contention for Ashe’s family, as well as for the citizens of Richmond. The monument depicts Ashe standing, tennis racket in one raised hand and a stack of books in the other, surrounded by children who reach up, toward him. The composition is apolitical in form, content, and symbolism. Rumors of War functions as its polar opposite. The bronze figure has dreadlocked hair pulled back into a ponytail. Battles currently rage across the United States—in public and private—over discrimination against Black people because of the personal or religious decision to lock their hair. People have been fired from jobs and children have been denied the opportunity to attend graduation ceremonies, as the legal system failed to protect them. The figure in Rumors of War also wears a hoodie, a contemporary symbol since the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin that references the perception of Black skin as dangerous. The symbolic hoodie recurs in the discourses of activists and artists as a form of protest and memorial. The figure is also wearing Nike athletic shoes, possibly a tribute to the brand’s advertising campaign with Colin Kaepernick, the professional football player and activist who knelt during the national anthem to bring attention to police violence against Black Americans. Rumors of War is therefore a monumental artwork that functions as tribute to those who lost their lives, not during some fight on behalf of the state but during some encounter in which they were killed by the state.

A man I did not know was shot on my doorstep. Early in the morning, I heard the shots and felt them vibrate through the walls of my underinsulated apartment. I opened my front door to find a Black man there, struggling to move. I imagine he was trying to squirm his way around the bullet that pierced him. A woman who was walking along the street stopped and tried to comfort him. We stood with him until police and paramedics came. We didn’t want him to die alone. An officer threatened to arrest us when we wouldn’t back away. Another Black man, this one in a uniform, threatened to arrest me because I didn’t want this Black man to die alone—his body, an armed extension of the state, my body, powerless. I refused to leave until I saw him in an ambulance. I watched for an hour or so as the cop circled like a territorial lion around the dying man. About a week later the news covered the story, stating that the man had died. No public protest, no memorials. I think about him often. I wonder, how evil would it have been for me to have never called the police, to let him die held by two strangers?

RIP Cowboy in Spray Paint and Chalk, Corner of St. Jose St. and Ashby Grove, 2020 [photo: TK Smith]

The term monumental is used to describe large-scale—often public—artworks. Although it emits power in scale, beauty, and sculptural language, Rumors of War cannot perform the function of a true monument—such as the ones it references—because it was not commissioned and is not under the care and protection of a civic body. Rumors of War is a monumental artwork commissioned by an art institution with its own institutional agenda and web of influencing powers, both economic and social. Wiley’s reliance on European aesthetic traditions to imbue his figure with the trappings of power contrasts with Audre Lorde’s assertion that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” In the case of Rumors of War, the master’s tools are the very same visual symbols of a power used to oppress Black people. The Black body has been objectified and used to incite terror, just as it has been used to revise and shift narratives. To address the growing call for diverse representation in public space, the question is: can artists succeed where the state fails?

No, but they can tell the truth.

Inspired by the profound absence of the 9/11 Memorial, contemporary multimedia artist Devin N. Morris and I entered a lively debate on the efficacy of monuments today. The most moving and impactful objects of commemoration I’ve seen are inexpensive, ritualistic, ephemeral. I laid my body in the street for four minutes, I laid a rock where that man was shot. My precious memory of my great-grandmother is tattooed on my neck. White people have torn and reformed the American landscape to suit their desires. Would there ever be a permanent monument that could capture the resilience and power of Black people? Will a monument that features the beauty of Black skin, Black features, and the diverse expressions of Black culture ever represent the power of equal citizenship? Devin smiled and said, “I don’t need a monument.” He shook his head, “I don’t need a monument. I’m a monument. When I’m gone, I’m gone.”

Don’t let them turn me into a monument after they shoot me down in the street.

***

This feature originally appeared in ART PAPERS Spring 2020 // Art of the New Civil Rights Era.

TK Smith is a writer, critic, and curator. He is currently a Tina Dunkley Curatorial Fellow in American Art at the Clark Atlanta University Art Museum. Originally from Iowa, Smith recently relocated to Atlanta from St. Louis, MO, where he received his MA in American Studies from Saint Louis University.

References

| ↑1 | The images included in this feature are part of “West Side Monuments,” a series of photographs by TK Smith of public expressions of mourning in the West End, Westview, and Mozley Park neighborhoods of Atlanta where Smith previously lived. |

|---|