Monumental Collapse

Jillian McManemin, Toppled Monuments Archive (Christopher Columbus Monument after its removal), 2020, Chicago, IL [photo: Paul R. Burley, courtesy of the Toppled Monuments Archive]

Share:

A recent surge in toppling monuments across the United States has provoked questions about the life of a monument after its destruction or removal. Such questions prompted me to create the Toppled Monuments Archive—an artist-run digital archive documenting toppled and removed colonialist, imperialist, sexist, racist, or Confederate monuments. I wanted to speak with Che Gossett about the archive, in particular after I read their tweet:

“Tear down all the monuments to slavery, especially jails and prisons.”

Che Gossett: One question I had about the archive is, do you think that there’s a risk that it could be captured by the state and used for criminalization?

Jillian McManemin: I momentarily paused uploading content to the website because I have to put everything through anti-facial recognition processes.

CG: Opacity, great! I think that’s the solution. I was watching some of the videos in the archive today, and I was thinking about artists and activists wanting to document a moment of uprising and how that also can be twisted by the state against the people involved.

JM: Absolutely. I was looking at the content in the archive, and I was, like, is this dangerous? I’m just an artist. I don’t have a hacker setup. I felt very naive but have since figured out which software to use.

CG: A lot of protesters in different cities have had their images tracked, and they’re followed up with.

JM: Yes, and there have been arrests made based on images and videos. Thinking about how my hand as an artist will be going in and changing these images is strange and interesting. There is a touch in that digital process of erasing someone’s face. In so many ways this relates to not necessarily my art practice but [other] contemporary art practices. If the images and videos of toppling monuments relate to performance documentation, then do anti-facial recognition processes relate to painting? How can we use contemporary art and technology in a way that takes the conversation out of this space where it’s all about these objects that are just dead weight? I want to use art in an impish way to approach something that feels really heavy and laden with importance. There was an article in Hyperallergic about one of the Confederate monuments being brought to the Houston Museum of African American Culture. John Guess said that putting the sculpture in a museum was an act of healing; giving context to the monument was an act of healing. I don’t agree with that. I’m wondering about different ways to approach this entire thing [so that] the object isn’t central.

Jillian McManemin, Toppled Monuments Archive (digitally manipulated and protected video of the toppled monument to Christopher Columbus on State Capitol grounds), 2020, Saint Paul, MN [courtesy of the Toppled Monuments Archive]

Jillian McManemin, Toppled Monuments Archive (digitally manipulated and protected image of the toppled monument to Christopher Columbus on State Capitol grounds), 2020, Saint Paul, MN [courtesy of the Toppled Monuments Archive]

CG: Saidiya Hartman says the afterlife of slavery is not only a social but also an aesthetic problem. I’ve been thinking about that a lot and thinking about the relationship between aesthetics, technologies, and abolition, and how artists are responding to carceral, anti-black, and state violence. The work of American Artist, for example, is about surveillance technologies, policing, anti-blackness, and the weaponization of the color blue by the police.

JM: I had my reservations, and with the elections we’re really standing in this spot where we don’t know. Things are escalating very quickly; it could escalate even faster in a way that could leave us—

CG: Especially when Biden is just as focused on the protesters as [are] Trump and the mayors and the governors [many of whom are Democrats] in states [where] a lot of the prosecutions of BLM activism are happening. It’s bipartisan, law and order as counter-insurgency. Racial liberalism is carceral liberalism.

JM: As soon as I started something that felt exciting, I got this bitter taste in my mouth. I [started] the project because I wanted to remove a need to preserve these objects at all, just to preserve the action. But then I was questioning myself even wanting to catalogue something ephemeral. On the flip side, if we don’t have radical archives, or people putting things together on another end, then it’s monolithic. It’s just the museums or it’s just money doing things. That’s the tension for me.

CG: I think it’s really powerful to watch [these monuments] get toppled. I wrote the tweet … out of that spirit. It’s demystifying racial liberalism that is so embedded. There’s the Confederate ones, and then there’s tearing down ones that are white supremacists [who] aren’t Confederates, showing the extent of the monumentalization of white supremacy in this country. The tweet was about [asking], how can we account for that? The same people [who] are tearing down these monuments are addressing those same issues. The activists are [also] involved in anticriminalization and prison abolitionist work. There’s such an intensity, but also an anticolonial and abolitionist continuum, right? It’s not just a residuum. It’s a present violence. Activists are connecting the historical monument to slavery and contemporary monuments to slavery—which [are] the jail, the prison, Wall Street, and property.

JM: As I continue the project, different things are coming out. A lot of what art does is make the revolution look really sexy, giving it that cinematic aesthetic, whereas revolutionary practices are actually about the long haul, not just those bursts of something falling down. But I was like, build this platform for this cinematic sensory experience so that people can get excited—it’s like listening to a song. For me, it’s not just visual, it’s the noise. People screaming in joy and the thud. I toyed with the idea of, when it seemed too scary to post these videos, just having audio.

CG: That would also be very powerful.

JM: There are all these potential art practices and materials. I’d like to consider this documentation as sculptural material, moving away from the sculpture of the monument. Like, no, this is the stuff; that’s not the stuff.

CG: It’s also about justice, because many of the monuments are being guarded.

JM: Yes, I was thinking about the act of toppling as an act of performance and as an act of resistance. A lot of these monuments are being removed by the cities. There have been other removals, and more after Charlottesville, [and] after topplings. These actions exist in pockets [of time]. This is maybe the biggest pocket—right now—that we’re in.

CG: That goes to show how change happens, right? That’s how activism works.

Jillian McManemin, Toppled Monuments Archive (Jefferson Davis monument before removal), 2020, Richmond, VA [courtesy of the Toppled Monuments Archive]

Jillian McManemin, Toppled Monuments Archive (base of the Francis Scott Key Monument after the statue was toppled by protestors), 2020 [courtesy of the Toppled Monuments Archive]

JM: But there’s a bitterness. I was contacted by this guy in Richmond [who was] working on Monument Avenue, running the crew [that was] taking the monuments down. He was sending me so much footage every day, super chaotically, but it was really exciting. I asked, “Where are they going?” He said that they’re going to storage and that the city would decide. Well, what does that mean? There are a lot of instances in which [cities say] that they are removing these monuments, and they just relocate them, or they get sold. There’s a Robert E. Lee monument in Dallas, which was removed in 2017 and was recently sold for $1.4 million [and moved to a private golf course]—

CG: —which is the history of the paraphernalia of racial slavery and lynching …. It’s an anti-black libidinal economy [see Jared Sexton and Frank Wilderson on this term]. It either circulates in the mainstream with racial liberalism—“honoring the past,” and even if there’s the demonization of the Confederacy, that’s a racial liberal kind of alibi—or it circulates in as private property and in spaces of white domesticity—homes—and in this case, the space of White, [male], middle- and upper-class leisure—

JM: —at a golf course. I decided the archive had to change again. What’s happening to these monuments after they get removed is a continuation of all of these other issues. Also, when these objects go to museums, they cost money. To store these objects costs money. To conserve these objects costs money. Big sculpture like this costs a lot of money. It’s cumbersome.

CG: What does the city do with the $1.4 million?

JM: I have no idea.

CG: There’s been a lot of momentum around defunding the police. The defund movement reveals how municipal budgets are devoting millions and sometimes billions of dollars to police. Settlements are paid out by municipalities after police violence and killings, and Wall Street—banks and corporations and firms—profit off of this arrangement, such as Wells Fargo and others, who were also central to the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis and the dispossession of Black poor people and communities. Thinking about abolitionist activists organizing for defunding makes me curious about where that money went.

JM: A lot of taxpayer money goes into the preservation of these monuments and Confederate landmarks, [such as] locations where they give Lost Cause tours [but] don’t talk about slavery. So, as exciting as a lot of these images are, there’s more going on.

CG: I think in terms of abolition, of the struggle against the prison. Carceral ideology can absorb the opposition to prisons and refract it back. Something like, don’t put trans people in prisons. As Cece McDonald states, prisons aren’t safe for anybody. Prison shouldn’t exist can get reformulated into a carceral feminist version of trans inclusion—in a jail cell—and the idea that prisons can be made safe. Abolition means keeping track of the shifting morphology of how the prison system works and justifies its existence and knowing that abolition is a protracted and perennial struggle. I think it’s interesting—just to go back to a continuum—how the energy of the flashpoint versus [how] you’re thinking about the afterlife of the toppling … didn’t end when it was fallen.

JM: They’re actively not ending the object in ways that are very creative. Private companies have gone with scuba divers into harbors, to fish these monuments out with cranes. The efforts are incredible. I think about sculpture a lot, and I’m totally mind–blown by these efforts. Then I feel nauseous because the amount of effort letting these objects live is so much more than letting so many people live.

CG: The resources, you’re saying.

JM: Yes. What you were saying about absorbing the opposition: I think about art in this way. It reminds me of the aesthetics of punk or modernism. How it meant something so anti-establishment, and then it gets absorbed. If I could build an archive that slips away at the same time as it upholds itself, then it would be successful. Which is why I’m thinking about the blurred–out faces and the audio tracks, making [the archive] less formal, because the project is anti-academic and anti-object in a lot of ways.

CG: I also think it’s really powerful, what you’re doing in terms of tracing the afterlife of these objects. It shows [how] it’s not just the white supremacist statue; it’s the institutions that are invested in its preservation and resituation in history. “The museum is a neutral space to host this object” is [an] antagonistic [claim]. It’s showing that the actors and the agents in this situation are bigger than the monument itself.

JM: When you think about this piece of material getting yanked from people’s hands, and pushed, and pulled out, and moved, it’s this control and aggression that’s hyperfocused on, maybe, a broken piece of marble face that used to be a cheekbone. It’s really fetishistic.

Jillian McManemin, Toppled Monuments Archive (red paint-soaked statue of George Washington in Washington Square Park, NYC), 2020 [courtesy of the Toppled Monuments Archive]

CG: The philosopher Giorgio Agamben asks, “Why does power need glory?” I think that’s a really interesting question in relation to monuments.

JM: The aesthetics.

I’ve been looking at all these images and thinking about Leni Riefenstahl films, how they’re composed, their composition and their symmetry, and [about] the insane beauty of Italian fascist architecture. Why are we drawn to these shapes and lines? But the monuments, there’s ribbons and drums unfurling … onto angel’s arms and wilting men.

CG: Although the Columbus statue got redecorated, right? I think that’s pretty cool. This counter-aesthetic thing—

JM: There’s been some really great ones. In Washington Square Park, someone just threw red paint on one of the statues, and it looked amazing. In Baltimore someone hung plastic Halloween severed hands—

CG: On Columbus.

JM: There have been a lot of interventions that are really amazing. There was a statue of Juan de Oñate in New Mexico, and in the 90s protesters sawed his foot off because that’s what he did to the Indigenous people [whom] he encountered. There are these interventions that the archive will find a way to represent. Power does need glory to exist. I think people are held, obviously by racism, but they’re also held by glory. It couldn’t exist without that veil of beauty. It just wouldn’t function in the same way. People who give the Lost Cause tours of the plantation houses, they talk about the crown molding for hours.

What would your creative solution be? Should we melt them down, take them into the middle of the ocean?

CG: Maybe it’s like following the money and thinking about redistribution. I think more about how abolition forces us not to just think about it as the struggle [ending] when the monuments come down. But there [are] monuments that still exist that have to be opposed. What do you think? I’m also curious what the activists who are doing it think.

JM: I’ve talked to a lot of artists and activists who want to have them melted down, and for the material—bronze—to be used in a different way. I want people to think of these monuments as public sculpture, because I do feel like there is potential there [for] seeing the absurdity of these objects in space rather than accepting them as parts of history.

CG: There’s the criminalization and this executive order. That’s recent? That’s the president?

JM: Yes.

CG: The criminalization of toppling monuments as its own archive of lawfare, basically.

JM: I was thinking about the curfew in New York City—

CG: The curfew is just such a signature of slavery, like lantern laws and congregating. Du Bois wrote about the criminalization of Black sociality. The curfew is part of a plethora of laws designed to prevent the assembly of Black people in public space.

JM: I was struck by how toppling monuments and the anxieties of looting were intertwined.

CG: Right, and the valuation of property over people, which is inscribed in the law.

JM: If we talk about the criminalization of toppling monuments, specifically, I feel as if that [valuation] would find life in other laws, like other property damage laws during the protests, and how that [focus on property over people] kind of unfurls ….

CG: That’s powerful because it brings it back to abolition, thinking about those nodes of criminalization.

JM: Right, and then, how do you convince people that objects aren’t living?

CG: Because you already value property that’s inanimate over animate people. Right?

JM: It gets a little bit mind–bending to try to talk to someone about that, because it seems so obvious that human life is more valuable.

CG: Already, inside the [statement] “life of the human,” there’s a racial hierarchy. “Human” is already predicated on Black death and Indigenous death—and the symbolic death of Black indigeneity. People have to unlearn a lot. The reason people wouldn’t value human life over property has everything to do with how the figure of the human is constituted through racial slavery and anti-blackness and colonialism, this has been shown in the work of Sylvia Wynter, Frank Wilderson, Fred Moten, Zakiyyah Imani Jackson, and other critical theorists in Black Studies. America is all about protecting property, like that couple with the guns [who] came out in St. Louis.

JM: Yes. And, where do objects—and where does sculpture find itself in this process of unlearning? What do objects look like if they’re not so important? Are they as beautiful? I’m not specifically talking about the monuments, but sculpture. Artists are obsessed with objects. We make them, and we want to put them out there. I keep finding myself wondering how to hold space for those desires while wanting to undo, and [to] find ways to let things be ephemeral, which is contradictory when we’re talking about archives. The monuments being pulled and pushed into people’s hands is about ownership. These evil objects on auction blocks replicate systems in a way that is exhausting—

CG: —how they mean so much to the state, and to society, and the level of criminalization and police showing up to surround and defend monuments.

JM: Of course, it is about what these things stand for. But when you zoom out a little bit and see police and two rows of fences around a sculptural object, there’s a wild level of absurdity. It’s a surreal portrait of what’s happening. I know that you can’t take the content away, but just thinking of them as objects offers a [glimpse] into the physical reality of police guarding stone statues. What modern sculpture and what minimalism tried to do was a total focus on material. All of those movements were really patriarchal. But focusing on the material, then watching the drama unfold around it, is madness. It would force an unlearning, and it would force a detachment from the symbolism that’s being so protected.

Jillian McManemin, Toppled Monuments Archive (removal of Stonewall Jackson statue from Monument Avenue in Richmond, VA), 2020 [courtesy of the Toppled Monuments Archive]

CG: I think about the Frank Rizzo statue in Philly, in front of the [Municipal Services Building], and how anti-gay he was, and his war on the Panthers and the RAM [Revolutionary Action Movement]. It’s a symbol of pride for some people, and something you have to walk by every day.

JM: It’s not just the police but [also] civilians with guns, guarding the statues. The toppled Columbus statue in Baltimore was not dredged from the harbor by the city but by private companies funded by Italian-American groups.

CG: It shows a mutual investment—whether it’s [by] the police or the White citizen—in the same symbols of white supremacy.

JM: In [Kenosha] the police let an armed teenager walk right by [them] after [he was allegedly] killing people; they are operating [at] different levels, but together. You have the police, and you have terrorists, and the lines are blurred, and that’s because they have been totally blurred this whole time.

CG: Whiteness is the blur.

JM: Blur makes me think of anti-facial recognition processes again, [of] trying to get a grip on all the different actors in the cinema of it, [of] people giving their personal money to do whatever they want with these monuments that were technically supposed to be for the public. The protesters are [toppling] them, and other civilians are retrieving them, and a lot of cities are upset because they aren’t even involved anymore. But when they are involved, and people are excited that they’re involved, there’s this huge disappointment, because these things just end up in storage. The public reckoning that’s promised is lost.

CG: I’m just thinking about the difference in registers, even, from a museum that wants to preserve history versus the kind of energy of saying this is part of a broader movement. You can’t disentangle those things for the people [who] are toppling the monuments. All symbols of white supremacy, all material realities of white supremacy, are supposed to come down. That’s what the project is about. It’s resisting a politics of redemption and recuperation.

Jillian McManemin, Toppled Monuments Archive (the remaining plinth of the Christopher Columbus monument), 2020, Baltimore, MD [courtesy of the Toppled Monuments Archive]

JM: In a macro way we’re looking [at] how we relate to each other. We can’t do it in a compartmentalized way. It just doesn’t work. That’s the point where I get really frustrated with museums. You can’t just surgically remove this object from the situation and put it on a petri dish and expect to be aligned with radical thought and radical thinkers and artists. People keep asking me, where do you see this archive going? Would you work with an institution? I don’t know. I’m frustrated at that kind of violent compartmentalization. Museums just keep failing. What we just saw with the Whitney—

CG: —yes. The limits of the museum. And continued audacity to do keep doing that.

JM: No limits to the audacity—

CG: —[of] taking Black anything and appropriating it, and using it for your own purposes, including Black struggle. These limits also speak to the institutional need for changes, the need for Black curators at museums. A 2015 study by the Mellon Foundation showed that only 4% of curators are Black. So there’s a need and a demand for a total shift in museology and curatorial praxis.

JM: There’s this trust people have that, if the monuments have plaques, and if they go to museums, that the problem will be solved. I don’t believe that at all. I wanted to make this archive because of that. We are watching cities, museums, preservationists, and archivists interrupt activism. All it does is make more work for people to preserve these things—to conserve, to archive—and it doesn’t look at the bigger swath of activist efforts, history, and resource distribution. That’s where my specific anger came from: watching one of these monuments get dredged up by the city. You just ruined this toppling. You wouldn’t let this toppling live, and you wouldn’t let this object die. That was where I got involved, because I’m tired of the interruptions.

***

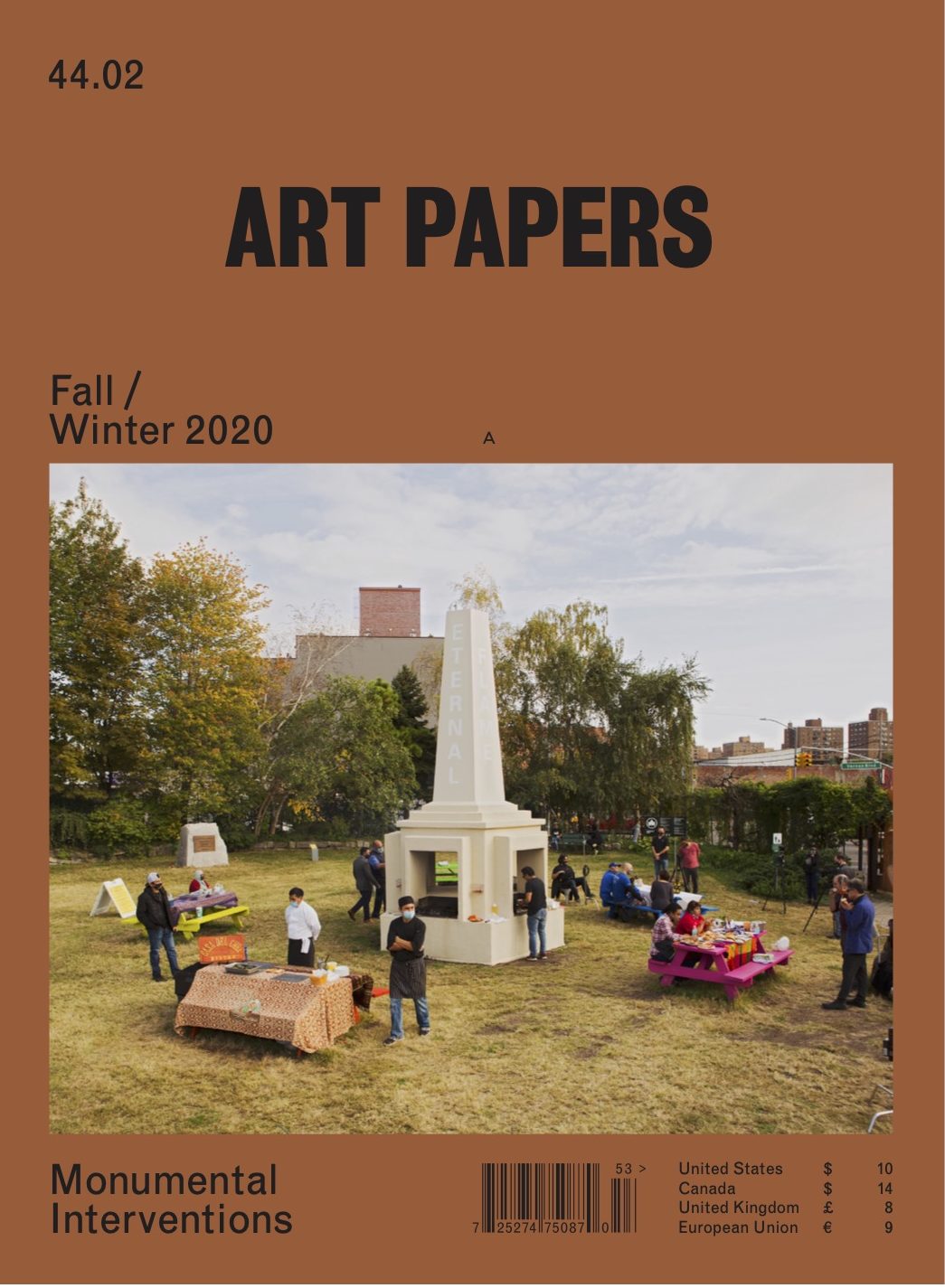

This interview originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Fall/Winter 2020 // Monumental Interventions.

Che Gossett is a Black nonbinary femme writer. They are a 2019–2020 Helena Rubinstein Fellow in Critical Studies, a Whitney Independent Study Program participant, and a 2020–2021 graduate fellow at the Center for Cultural Analysis, Rutgers University New Brunswick.

Jillian McManemin is a queer multidisciplinary artist and writer whose work has appeared in BOMB, Hyperallergic, Art-agenda and The Brooklyn Rail, among other publications. She has performed and presented work at Anthology Film Archives, MetLiveArts, The Poetry Project, Dixon Place, Invisible Exports, and the Knockdown Center. She recently founded the Toppled Monuments Archive, and she is working on her first book, Sculpture Kills. She is based in Brooklyn, NY, and is currently the exhibitions manager for the estate of David Smith.