Meredith Monk & Nurit Tilles

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS September/October 1988, Vol. 12, issue 5.

These interviews were conducted when Meredith Monk appeared in concert, accompanied by Nurit Tilles, at Seven Stages Collective Theatre, Atlanta, February 5 and 6. Monk has been performing for the past two decades as a musician, vocal artist, dancer, choreographer, and filmmaker. Her works connect and transcend the boundaries of traditional art disciplines. Tilles is known for her performances of contemporary avant-garde compositions and is a member of Steve Reich and Musicians. Both interviews were arranged for Art Papers by Quantum Productions.

Mildred Thompson: I find your music extremely visual. I was wondering if music is visual to you.

Meredith Monk: Yes. I love to do music concerts because they give the audience a chance to have their own images. I’m always trying to combine these elements so that you get a full experience, not only musically but visually as well.

MT: There were sounds reminiscent of the out-of-doors, of open space, of auctions, or tobacco sales; the songs with insect sounds made me wonder if you have some special involvement with the natural world.

MM: All of our environment is inspiring in one way or another. It took a long time for me to actually think that New York could be inspiring as an environment. You could say that a lot of my work has a pastoral quality. Because it’s very difficult to find space and silence in our culture, I wanted to hear and see those things in theater. “Songs From the Hill” is very much built on silence as a real element in the music.

MT: And the insects?

MM: Once I was in New Mexico and I just started listening to the sound of an insect. Suddenly I started looking at the insect’s movement, and listening in a way I hadn’t before. I realized that there are all these things that are going on all the time that our awareness is not attuned to. It’s interesting how much we miss all the time. A lot of it has to do with slowing down enough to be able to literally appreciate reality.

MT: While watching your film Ellis Island the term genie de lieu kept coming back again and again in my mind.

MM: I felt it very strongly the first time I went there—I almost started crying because I felt that all those people’s souls were dancing around in the halls. It had such a haunted feeling to me, so I felt that I wanted to make a ghost story. The project was a chance situation. My friend Louise Steinman called me up one Saturday and said “Would you like to go out to Ellis Island?” It was very haunting—June 10, 1954 was the day the last person was there (not going through as an immigrant, because for a while the Coast Guard had Ellis Island) and everyone just left and left everything there. So the calendar was still on June 10, 1954, the keys were still on the doors, and there were even little baby shoes and clothing from the immigration time. It was as if it was an archeological site with all the layers left intact. I was stunned by the timelessness of the place. I realized that it would have been hard for me to do a theater piece there and bring an audience out to Ellis Island, so the best thing to do with that experience was to try to make a film. It also became a film about processing human beings. It’s done in a light way, but there is an iconoclastic aspect on a political level, because it was a really horrifying experience for everybody that went through it.

MT: Do you feel that the avant garde in music is futuristic or is it more involved in recreating something from the very distant past?

MM: I actually think of it as both. I try to make it as if time is a circle. I think that the voice can uncover whole levels and shades of feelings that are probably less refined than they were, especially in this country now where everything is so fragmented and television is numbing everybody’s senses and there’s a lot of suffering. I think that these feelings are something art can affirm. Certainly the voice can. It’s very emotional, there are a lot of subtle colors to it. It gets between the feeling states that we have words for. In some ways it brings back that memory that we all have in our unconscious, that legacy of full- heartedness and full-feelingness. At the same time, it also goes to the future. You could say that the only reason to do art at a time like this is to affirm some of these things we have lost. Otherwise, other things, like technology, can do it better. For example, Western culture is the only culture that separates music, dance, and storytelling or theater. That’s already a direction that’s so fragmented in terms of the human organism or the human body. People still have a very hard time with that separation; I’ve had a terrible time with people being terribly upset because they can’t categorize me. “Well, you’re not really a musician because you also do theater. So then it can’t really be music because you’re such a good actress. How could it be that you’re a good musician?” “Well, you’re not really in theater because you’re spending almost all your time doing music. So it can’t really be theater because it’s not a play.” “Well you’re not really a dancer…” It just goes around and around. It’s been twenty five years of that for me. It’s sort of like banging your head against the wall, but what else can we do? I ask myself many times what the point of doing art is; maybe I could be more helpful working for the homeless or working in a hospital. But I think there’s a real need for this kind of affirmation of the human spirit. I think the voice itself is a language, and so it is the text. What I try to do in every song is to make it as specific as text would be. Emotionally, it’s that specific.

MT: That is its strength. It isn’t imitating anything except…

MM: What it is. There’s a sound for almost any human experience, and I think that basic goodness also includes pain. Pain and joy are part of the human experience, and if you cut off one half there’s something that’s not truthful about it. You need to have that shadow side expressed; otherwise, a whole culture pretends that that side doesn’t exist and then it ends up happening like 1938. It doesn’t make any sense. It’s much more interesting and vital to live all the human experience than to pretend that something doesn’t exist and then numb out.

MT: What did you do in Germany?

MM: I’ve done a lot of work in Germany, which is ironic because I’m Jewish. My best audience is in Germany, which is interesting for me. I worked with an ensemble in West Berlin, on a big piece called Vessel in 1980, an old piece which I revived. It had about 150 people in it in three different places. The audience took a bus from one place to another. Berlin became the subtext of this piece, as New York had been in 1971. In 1983 I went back to Berlin, and made a piece called The Games in collaboration with Ping Chong.

MT: And who do you think is your American audience?

MM: Now I think once we get to an audience, almost anybody. The problem we have now is the government, the way the money has been taken away from the arts and education. People have a difficult time bringing in something that can’t guarantee a sold-out house. I don’t think they’re afraid themselves, I just think they have to answer to someone else, have to make sure their big houses are sold out. So they’ll bring in someone like Frank Sinatra. At the same time, ironically, I think the audiences are much more interested in listening to music like this now, they’re ready for it almost everywhere. Generally, there are all kinds of people in a music audience, but in the theater, I think they’re more conservative. When we did Vessel in Berlin (1980) at the Schaubühne it was in a young people’s area and a Turkish community. Now it’s on Kürfürstendamstrasse and it’s almost like Fifth Avenue. Those audiences! I used to sit in the back of the theatre and say “That one’s going to leave, that one’s going to leave…” The poodle crowd was definitely not going to stay to the end of the piece. In a way, that was the end of the Schaubühne when they changed to a monolithic new theater, because I think they lost the vitality of their audience.

MT: You are now working on an opera?

MM: Eventually I am, for Houston. Right now I don’t have my total libretto or theme; it’s not going to be an opera that has many texts, so these poor opera singers are going to have to learn how to do different kinds of extended vocal techniques in opera format. I went a few years ago to teach them Dolmen Music in Houston, and it was like “when worlds collide.” But they ended up singing it very well. Incidentally, I think that the black singers were able to deal with this music better than the white opera singers. I think that’s because their musical education was more varied; dealing with a different kind of sound level didn’t give them as much trouble mentally.

MT: A lot of black children’s games are related to an African heritage where music is still very much a part of life.

MM: I think there’s a very full-bodied idea of music, a very kinetic sense where the voice and body are one. Somehow within black culture, music is not so isolated from experience. I always do physical warm-ups at the beginning of rehearsals, and one of the black singers in Houston told me he felt that it was such a cleansing way of working. Some of the others had a harder time with that. I felt that the black singers were more open-minded to different ways of singing. They didn’t think their instrument was going to be hurt by doing something else. Other kinds of voice production are not so foreign to them, whereas people who have only done classical singing have been taught that there’s only one correct way to make a sound, and if you do anything else your instrument is going to be ruined. It makes for incredible neurosis. But it ended up that everybody sang from the bottom of their hearts, and they didn’t hurt their voices. They worked through a lot of their resistance, and sang it very well. The audience loved it, too. That was my first experiment with opera; now I’m going back to work on another piece with the working title Three Nights. It’s going to be three different nights in history, based on one element— night—but with three different acts in different places of the world. Three different atmospheres, but all at night.

MT: I wanted to ask you about your workshop, The House.

MM: My company is called The House. There’s also my vocal ensemble, but the people in The House are more “mixed pickles” types like me with music and theater backgrounds. The members of the company teach workshops two or three times a year. You just call up my office and find out who is teaching; anybody is welcome. The workshops combine movement warm-up, vocal work, and some theatrical problems.

MT: Do you think there should be a new language for this kind of “new” music? That we should remove words like “concert” or “opera”? Are these stigmas?

MM: Definitely. I think that’s one of the reasons why there isn’t much of an audience for opera now, because it implies a 19th century form or format. I like to think of it all as “music theater,” because that includes everything— what is called opera, Broadway shows, anything that combines musical and theatrical forms.

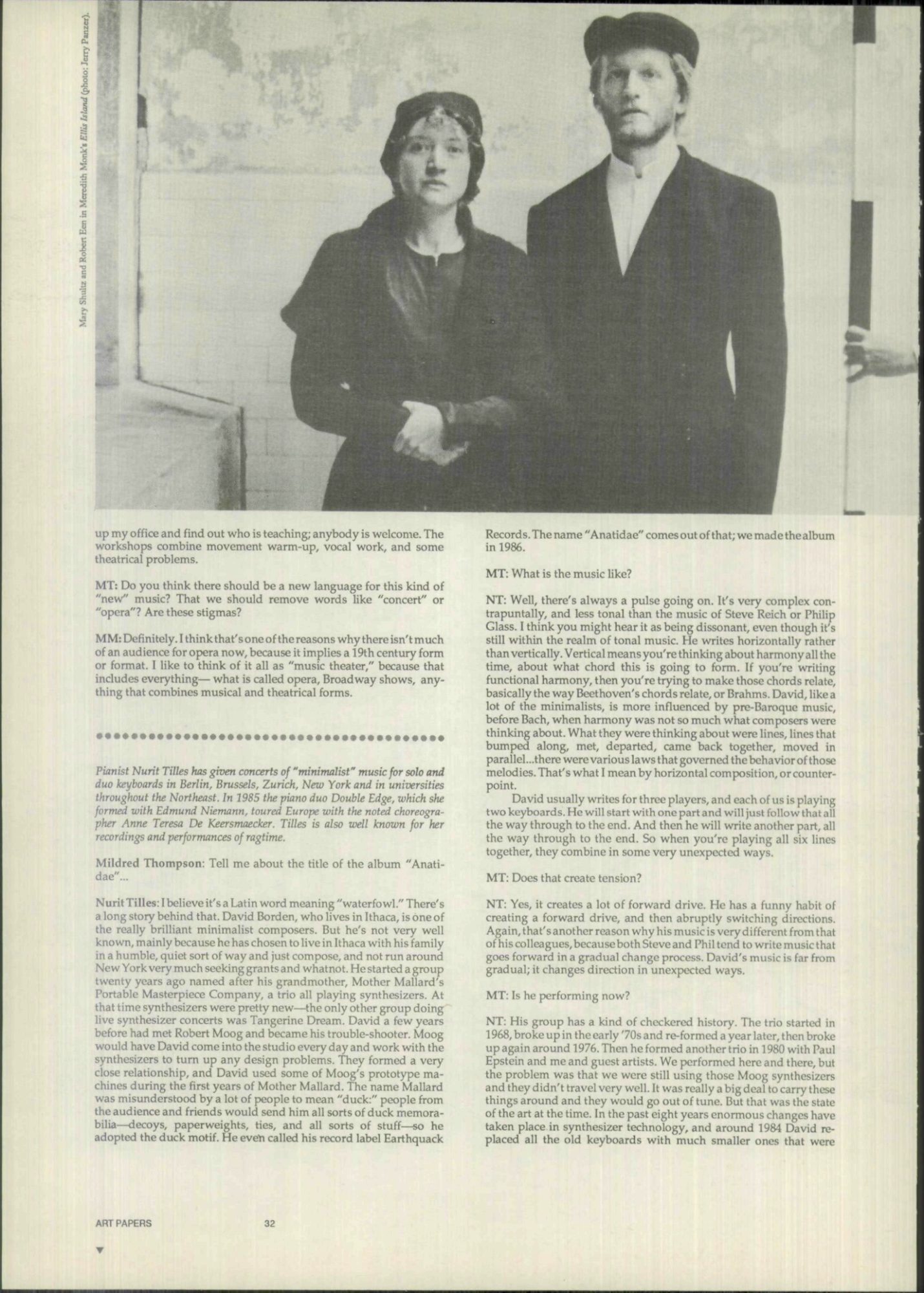

Pianist Nurit Tilles has given concerts of “minimalist” music for solo and duo keyboards in Berlin, Brussels, Zurich, New York and in universities throughout the Northeast. In 1985 the piano duo Double Edge, which she formed with Edmund Niemann, toured Europe with the noted choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaecker. Tilles is also well known for her recordings and performances of ragtime.

***

Mildred Thompson: Tell me about the title of the album “Anatidae”…

Nurit Tilles: I believe it’s a Latin word meaning “waterfowl.” There’s a long story behind that. David Borden, who lives in Ithaca, is one of the really brilliant minimalist composers. But he’s not very well known, mainly because he has chosen to live in Ithaca with his family in a humble, quiet sort of way and just compose, and not run around New York very much seeking grants and whatnot. He started a group twenty years ago named after his grandmother, Mother Mallard’s Portable Masterpiece Company, a trio all playing synthesizers. At that time synthesizers were pretty new—the only other group doing live synthesizer concerts was Tangerine Dream. David a few years before had met Robert Moog and became his trouble-shooter. Moog would have David come into the studio every day and work with the synthesizers to turn up any design problems. They formed a very close relationship, and David used some of Moog’s prototype machines during the first years of Mother Mallard. The name Mallard was misunderstood by a lot of people to mean “duck;” people from the audience and friends would send him all sorts of duck memorabilia—decoys, paperweights, ties, and all sorts of stuff—so he adopted the duck motif. He even called his record label Earthquack Records. The name “Anatidae” comes out of that; we made the album in 1986.

MT: What is the music like?

NT: Well, there’s always a pulse going on. It’s very complex contrapuntally, and less tonal than the music of Steve Reich or Philip Glass. I think you might hear it as being dissonant, even though it’s still within the realm of tonal music. He writes horizontally rather than vertically. Vertical means you’re thinking about harmony all the time, about what chord this is going to form. If you’re writing functional harmony, then you’re trying to make those chords relate, basically the way Beethoven’s chords relate, or Brahms. David, like a lot of the minimalists, is more influenced by pre-Baroque music, before Bach, when harmony was not so much what composers were thinking about. What they were thinking about were lines, lines that bumped along, met, departed, came back together, moved in parallel…there were various laws that governed the behavior of those melodies. That’s what I mean by horizontal composition, or counterpoint.

David usually writes for three players, and each of us is playing two keyboards. He will start with one part and will just follow that all the way through to the end. And then he will write another part, all the way through to the end. So when you’re playing all six lines together, they combine in some very unexpected ways.

MT: Does that create tension?

NT: Yes, it creates a lot of forward drive. He has a funny habit of creating a forward drive, and then abruptly switching directions. Again, that’s another reason why his music is very different from that of his colleagues, because both Steve and Phil tend to write music that goes forward in a gradual change process. David’s music is far from gradual; it changes direction in unexpected ways.

MT: Is he performing now?

NT: His group has a kind of checkered history. The trio started in 1968, broke up in the early ’70s and re-formed a year later, then broke up again around 1976. Then he formed another trio in 1980 with Paul Epstein and me and guest artists. We performed here and there, but the problem was that we were still using those Moog synthesizers and they didn’t travel very well. It was really a big deal to carry these things around and they would go out of tune. But that was the state of the art at the time. In the past eight years enormous changes have taken place in synthesizer technology, and around 1984 David replaced all the old keyboards with much smaller ones that were digital, hence stable in tuning. Touring would have become much easier, but some other complications arose, for instance, the difficulty of rehearsing with two members of the group living in New York City and one upstate. Nothing stops David from composing, but the business end of it is not his cup of tea at all. He really is just interested in the creative end of it.

Around 1982, I said in a rather surly way to David, “Well, this synthesizer stuff is all very well, but I’m really a pianist, I wish you would write some piano music.” And he actually did write a duo for two acoustic pianos, called The Continuing Story of Counterpoint, Part 2. Then a couple years later, David wrote another duo, The Continuing Story of Counterpoint Part 11 for me and Edmund Niemann, who had joined the band. Ed and I perform together as a duo-keyboard team, Double Edge. Last year I asked David for another duo for Double Edge’s debut in Town Hall, and he wrote us a beautiful piece called Double Portrait.

MT: So the music that Double Edge plays is…

NT: Well, we play much more than David Borden but our repertoire does include the three duo pieces. So in that way David’s music is heard. Also he reformed the trio yet again with a very good wind player and composer named Les Thimmig, who is from the Midwest, and David Swaim, a keyboard player who specializes in synthesizer improvisation. They’ve gone in more of an improv direction. In the meantime he’s finished up “The Continuing Story of Counterpoint,” a series which he began in 1976. He planned it to be composed of twelve pieces, each about ten minutes long, and as he would compose a new part we would premiere Parts 1-3, Parts 5-7….Part 12 has finally been finished. So now the whole “Continuing Story of Counterpoint” exists, and we would like to give it somewhere.

Double Edge performs pretty much the range of everything that’s been written for two pianos, but most of our repertoire is 20th century, with an emphasis on the minimalist works. That’s how Ed and I met, in Steve Reich’s group. We began as a duo in 1978, playing Steve’s Piano Phase and a piece by Paul Dresher called This Same Temple.

MT: There are comments lately that music is going in the direction of poetry in that poets are writing for other poets, and musicians are composing and performing for other musicians.

NT: I think it’s definitely true of certain branches of composition—the serialists, the whole movement that began with Schoenberg and Webern, and what has been termed the academic composers. There exists music that is fairly inaccessible to the non professional listener, that can be appreciated most by musicians, by looking at the score and admiring the structural intricacies. What we try to do with that is to have a balanced program with respect to “difficult atonal” music. That’s really to represent that style, just to show it as one of the things that’s being done in music today: there is something to be said for it, there are certain enjoyments to be gained. I do think it’s very unhealthy when musicians are composing and performing solely for other musicians.

MT: It is said that there is a sort of incest that results from this very strong academic, intellectual thing, and it becomes very closed like esoteric mystical groups.

NT: I question whether the parallel fits. Because the esoteric mysticism to me is necessary only for those who don’t have the immediate grasp of truth that children have. It’s kind of the adult’s way of seeking something that’s right under our noses. If you follow that, to me as a listener, the academic composers are not in direct contact with any kind of very simple truth. That’s where one kind of esoterica does not equal another kind of esoterica. Those musical esoterics, although individuals among them are brilliant, in their artistic expression are not exploring simplicity or balance. I don’t think mass audiences are an absolute good either. A limited audience is not necessarily sterile, but it’s not necessarily in possession of truth. I can think of some other kinds of music that are also going to have very limited audiences. Eastern traditional music, taken outside of its culture, does not receive a mass audience. But that’s for a different reason—because it’s based on totally different cultural assumptions from our own, and a different language, we can’t receive it in a way that’s truly meaningful to us. The problem with the academic composers is that some have developed various languages that are only self-referential. It’s so far removed that it would be like you and I going to a lecture on a very familiar topic, but in Sanskrit. We can only admire from afar, and say “What wise men these are.” I don’t want to speak Sanskrit to people; I would like to introduce some fascinating new words that I happen to know because I’ve travelled somewhere else, but I want to introduce them speaking the language of the people I’m speaking to. This is one of the reasons that I work with Meredith Monk, because although her musical language is unusual and experimental, her communication with listeners is direct and immediate.

When an art really works, to me it’s because it appeals on the sensual level, on the emotional level, on the structural level, and on the craft level, of being beautifully finished. To me even the finest serialist works lack some of the qualities necessary for balance. One of those is a kind of wildness. A good work of art is always paradoxical, there’s always a freedom versus the limitations of thought; we could say everything, but then it will be chaotic. We’re after contained chaos. That’s one of the things I think goes through all of Meredith’s work, and of other composers I admire, this wild emotionalism which is very carefully crafted. That is artistry to me, and that’s what I don’t find in works composed for the sheer intellectual joy of it. There is joy in intellectualism, but it’s not enough to be art. Art has to have all kinds of craziness in it, emotions and an understanding of people’s physical selves. If it doesn’t appeal on a kinetic level, it fails as music.

MT: That’s true of a visual piece as well. I tell this to my classes all the time. So much visual work is so slick, it’s devoid of emotions. That’s probably true of all of the arts: the more it gets away from the human level, the more shallow it becomes. So many artists are either ashamed of that or afraid of it.

NT: In musical performance there are certain standards that are drilled into us which we must respect. We as performers are at the service of the composers; in a sense, we are not such independent beings as they are. Nevertheless, even within our field of performing, there is the issue of balance between wildness and craft. There are the “slicks,” the note-perfect performances that don’t have that hint of freedom. In the great artistic performers there is that paradox again. You have the highest standard of refinement and control over the instrument which in the best hands leads to a feeling of soaring freedom. You can do anything you want because you have so much control. My life is devoted to trying to get maybe a few glimpses of that. I started working with Steve Reich in 1975, when I was in my early 20s. I was delighted to find him and his music. I was going through a lot of anguish about what kind of music 1 was going to play. I had been trained very well in classical playing, and I loved it, but I didn’t see why I should spend my life playing Beethoven when there were lots of other piano students about to do the same thing, some of them much better than me. I wanted to contribute something else. I was at Oberlin at the time, and started to play 20th century music, but I ran into those problems of not feeling a kinetic and sensual connection to them. So I began to study ethnomusicology, but then I felt, well, I’m a nice Jewish girl from New York; as interesting as all these non-Western traditions are, I am not about to run off to India. It doesn’t make sense. I don’t have a right to do that. I can do it, but it’s kind of a substitute life.

MT: No matter how much you understood it…

NT: I could never be inside their culture. In 1974, I met Steve, and he had found a very beautiful and creative solution to this dilemma, which was to take from some non-Western traditions certain principles, and then integrate them into a Western instrumentation. He wasn’t stealing it blind or making an exotic thing; he was being inspired by it. I’ve had the good fortune to be in his ensemble, I’ve had the good fortune to be in Meredith’s ensemble. I’m in contact with some of the really wonderful composers of our time. 1 think it’s their destiny to have thought of something very new and very old, and to have integrated and connected it in work that is individual but still means something to many people.