Men in High Castles

Since last November, for reasons that feel obvious, counter-factuality is in the air. Assumptions have been upended, and even the most basic logic of cause and effect has slipped out of our hands. Will we find out that this election was all a dream and wake up in the real world? We can't predict the future. We also can't explain how we got to the present, not really. We're left with endless, head-spinning revisions of the past.

Share:

In short, it’s a prescient moment for season two in Amazon’s ongoing adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s 1962 novel, The Man in the High Castle. Dick’s vision of a world where the Axis powers won the Second World War is expanded and rewritten by show-runner Frank Spotnitz to suit the way we watch things now. Each episode flows into the next, the gray opening credits streaming past striking graphics representing German and Japanese armies as they converge on a map of the United States, silhouettes of airplanes and parachutes on US icons, shadowy and half-real, and dreamy.

Then we wake up in Spotnitz’s postwar America, and—as is true of our own 2017—it is no dream. The light is sharp; the details are stylish and precise. Wholesome, whitebread touchstones arrive distorted, and evocative, but not evoking what we think we know about our country in 1962, making us question our own assumptions about what those touchstones signify. We follow Joe Blake, Juliana Crane, and Frank Frink as they face distinct dilemmas. Who will collaborate? Who will resist? Conspiracies pile on top of conspiracies, tangles erupt between the German and Japanese forces, and you can assume that the kindly old man who rescues you in his pickup truck will talk like a member of the resistance, and then put a gun to your head and turn you over to the Reich.

As they say in Spotnitz’s old show, The X-Files, The Truth Is Out There. But what on earth does all of this have to do with Dick’s original novel? What would a fan of the series make of the book?

The answer, it seems: they’d be befuddled. One reader who couldn’t get past the first few pages said to me, “It seems to be mostly about antique stores.” I’ve also heard criticism about the novel’s portrayal of Mr. Tagomi, the Japanese trade minister, who speaks in a kind of pidgin English. Granted, as Ursula K. Le Guin pointed out in her 2015 introduction to the Folio Society edition, everyone in the book speaks in that same telegraphic, fragmented, and article-free English. And yes, there are numerous scenes in antique stores, and very few Nazis. The novel takes place almost exclusively in Japanese-occupied San Francisco, and in the Rocky Mountain States neutral zone where Juliana lands after a failed marriage to Frank. She runs into an Italian truck-driver named Joe Cinnadella (who becomes Joe Blake onscreen) and they have energetic, excellent sex; then he buys her fancy clothes and plans to take her to meet Hawthorne Abendsen, the famous author of The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, who’s also known as the Man in the High Castle.

In fact, Dick’s novel has none of the torture chambers depicted in the Amazon series and no Nazified American flag, but it does have many, many pages in which very little happens. The story opens with Childan, an upscale dealer at American Artistic Handicrafts, preparing to sell antiques to elite Japanese occupiers. As in the adaptation, Frank works in a factory that creates counterfeit antiques. Over and over again, Dick fixates on questions of authenticity. What passes as the story arc concerns a German official posing as a Swedish industrialist. Still, the false names and subterfuge feel petty and disjointed. An antique gun gets fired. A German agent gets his throat slit with his own razor. These desperate actions are isolated and don’t add up to any picture of widespread conspiracy. It’s striking—particularly after viewing the series—to return to Dick’s novel and realize that it describes no organized resistance to the Japanese or the Nazis.

In fact, Dick’s novel has none of the torture chambers depicted in the Amazon series and no Nazified American flag, but it does have many, many pages in which very little happens.

Stills from The Man In The High Castle, 2016

Spotnitz’s adaptation asks, “Whom can I trust, and what should I do?” Dick’s novel asks a different question: “What’s true or false, and how can I tell the difference?”

In short, Spotnitz is a show-runner, and Dick is a Gnostic.

In 1974, after a trip to the dentist to remove an impacted wisdom tooth, and under the influence of sodium pentothal and Darvon, Dick came to believe he’d achieved direct, intuitive understanding of all knowledge, human and divine. This state of grace—along with epileptic/psychedelic light-shows, and conversations with a wise ceramic pot and someone named Thomas who lived in the Roman Empire during CE 70—lasted until his death, five years later, and resulted in boxes of notes that were eventually edited and published as Exegesis in 2011. In that book Dick observes, “The schizophrenic is a leap ahead that failed.” As far as Dick was concerned, he wasn’t schizophrenic, and he hadn’t failed, any more than any Christian mystic. His heightened awareness was heightened sanity, and the culmination of his life’s work as a thinker and a writer. In a series of posts for The New York Times, “Philip K. Dick, Sci-Fi Philosopher,” Simon Critchley makes the case that Exegesis should be taken seriously, and that all of Dick’s work should be read in light of Exegesis and most centrally in the context of Gnosticism.

Gnosticism is a second-century synthesis of Christian and Pagan philosophies. Gnostics believe that the universe was created by a “Demiurge” (“public worker” or “craftsman”). This subordinate god maintains a material world that is inherently flawed and filled with needless suffering. In some ways Gnosticism is an elegant solution to the problem of evil. If God is omnipotent, omniscient, and benevolent, why do people suffer? They suffer because the “craftsman” that created us is not, in fact, benevolent at all. The Demiurge follows a relentless, amoral logic, like an illness spreading through a human body. Evil exists. Nothing can justify that evil or make it go away.

However, there is a real, all-powerful God in a separate, secret realm beyond material creation. This God creates nothing, stands outside of time and space. A divine spark of this true God lies within each of us; it is the possibility of salvation. This revelation does not come about through an act of will, certainly not through loving our neighbors and doing good works. We cannot know when and how salvation will emerge. Thus, Dick rejects the craftsman’s conventional belief in cause and effect, the correspondence between a character’s action and its consequence. It’s no coincidence that, in Exegesis Dick writes: “the core of my writing is not art, but truth.”

In his novel The Man in the High Castle, Dick is no craftsman. Most of the characters appear to have no will of their own, and the free choice that drives contemporary fiction eludes them. When faced with a crisis, they turn, again and again, to the Taoist oracle: the I Ching. Using coins or yarrow stalks, Americans and Japanese alike consult the oracle, and they spend a long time poring over its answers. Frank, Juliana, and Tagomi all use it regularly. Here, Tagomi addresses Baynes, the faux-Swede whom the trade minister knows is not the man he claims to be, yet inherently trusts, and explains, in his elliptical way, why he chooses to trust him (because Tagomi had consulted the oracle):

“We are absurd,” Mr. Tagomi said, “because we live by a five-thousand-year-old book. We set it questions as if it were alive. It is alive. As the Christian Bible, many books are actually alive. Not in metaphoric fashion. Spirit animates it. Do you see?”

One of Dick’s American characters notes that the I Ching is a method of divination of Chinese origin. One can’t help wondering whether Dick, who worked for years in a record store, was thinking of John Cage, who composed so much of his music by consulting what Tagomi calls “the oracle.” Ritual and chance, on one hand, both open up a way to let truth in. Art, on the other hand, is another word for artifice. In other words, it’s just another lie.

Frank also consults the oracle; on its advice, he quits his job in the factory that makes counterfeit American artifacts and starts to create silver jewelry of his own creation instead: abstract, free-style forms, “designs which to some extent the molten metals had taken on their own.” The pieces find their way to Childan’s shop, and a Japanese client informs him that they have “wu“:

[the] hands of the artificer had wu, and allowed the wu to flow into this piece. Possibly he himself knows only that this piece satisfies. It is complete … and by contemplating it, we gain more wu ourselves. We gain the tranquility associated not with art but with holy things … I have come to identify the value which this has in opposition to historicity.

What is wu? Dick does not translate for us, but it is a Chinese character for “shaman, or spirit medium.” How is the state of having wu in opposition to “historicity”? Spirit exists outside of time.

If art is created by chance, rather than intention, can it transcend the Demiurge, the prison of our material world? Can it be a medium for transformation? Can it tear the veil between material and spiritual, false and true? In fact, can Dick’s own novel, which—rumor has it—was constructed, Cage-like, in conversation with the I Ching, make the ground shift under our own feet?

It’s clear that Spotnitz envisioned his adaptation of Dick’s novel as homage, and that he also understands that an adaptation demands flexibility—extended or excised plot lines, new characters, and (most of all) the visual treatment that Dick addresses minimally. Yet these adjustments to the original materials change their deeper structures and meaning in ways that Spotnitz himself may not realize.

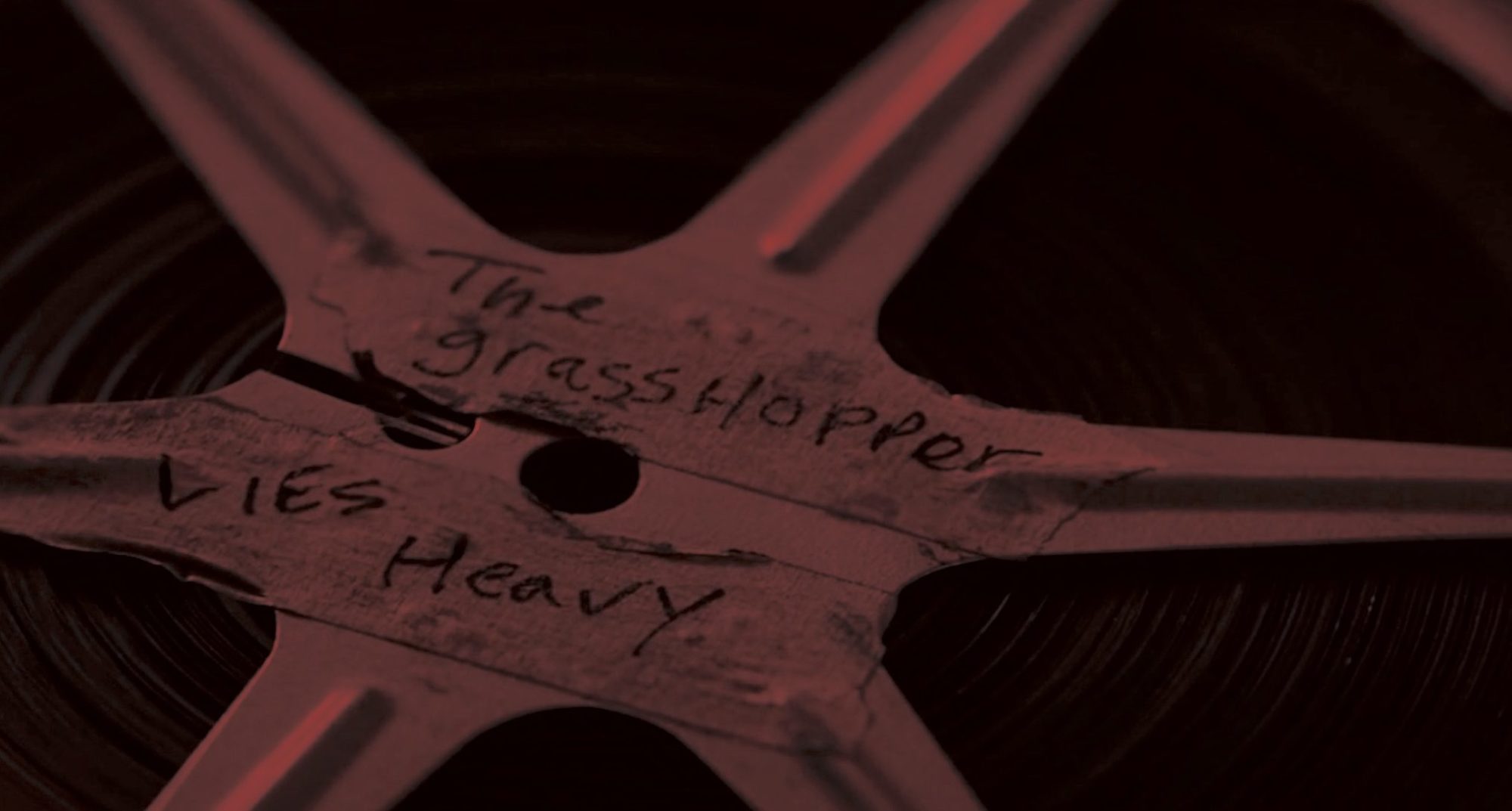

Perhaps the clearest example of Spotnitz’s impact is his most critically celebrated choice to turn Abendsen’s The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, the novel within Dick’s novel, into forbidden films within a film. In Dick’s book, The Grasshopper Lies Heavy isn’t forbidden, at least not on the West Coast. It’s even a best seller in Japan. Everyone seems to be reading it—a counterfeiter’s mistress, Joe Cinnadella, even the Reich’s Consul in San Francisco, who reads a copy in secret while contemplating the assassination of its author, yet acknowledging that its version of history and Germany’s defeat felt “somehow grander, more in the old spirit, than the actual world.” Distinctions between Abendsen’s alternative history and our own world are marked, with Rexford Tugwell rather than Franklin Roosevelt as president in the 1940s, and England and America engaged in a trade battle that leads to a new world war, but this imperfect truth is subversive, and it’s public knowledge. This knowledge doesn’t lead to much of anything but knowledge. That’s enough.

Stills from The Man in the High Castle, 2016

Compare this to a reel of The Grasshopper Lies Heavy in Spotnitz’s treatment, screened by Juliana as she gazes with tear-filled eyes upon images of Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin at Yalta and the bombing of Hiroshima. These newsreels are so iconic to us real-world viewers that we’re not surprised when Juliana instinctively knows they’re true with a capital T. That Truth—embodied by those reels of film—is Out There, X-Files style, though shrouded by conspiracy and mystery, passed from hand to hand at great cost. It’s the foundation for resistance to the German and Japanese occupation. Juliana, Frank, and their comrades don’t trust each other. They trust the film. Or if they don’t, they should. And then they take out their maps and load their revolvers and prepare to change history.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the Gnostic term for the god of the material world, demiurge, is sometimes used to describe a person who is the creative force behind a successful enterprise, as in “Frank Spotnitz is The Man in the High Castle‘s demiurge.” Certainly, Spotnitz is a craftsman. There is nothing random about the world he has created, and at points this reasoned approach has put him in an untenable situation because he clearly seems to love the random, often incoherent, novel he adapted. Spotnitz stepped down as show-runner in the middle of the second season, citing creative differences, and as of this writing, details of his departure are unclear. In a December 2016 interview with The X-Files Lexicon, he said, “I had a very different idea about where I wanted the show to go and what I wanted the stories to be.” Could the creative differences have involved Spotnitz’s insistence on using Dick’s book as a touchstone?

In some respects, the show might be better served if it shook some of the Dick novel’s dust from its cowboy boots. Nothing Spotnitz translates directly from the book quite works. Frank turns into a failed assassin and incompetent rebel because watching someone polish jewelry is just too boring. Juliana, who is on her own in the book, gets an extended family and a travel allowance, but she has no discernible personality. Joe Cinnadella-turned-Blake is worst of all, a puppy dog of a double-triple-quadruple agent, seemingly designed by a team of market researchers as a love interest for Juliana and a foil for Frank, as he’s more “likable.”

Some of Spotnitz’s attempts to reference the book feel oddly arbitrary. In a season one episode called “End of the World,” the antiques dealer, Childan, shows a member of the Japanese elite a piece by Frank. Unlike in Dick’s novel, the piece is not original jewelry, but a counterfeit of Sitting Bull’s necklace, the meticulous work of a craftsman who was determined to raise money to leave the Pacific States with Juliana. The client looks at the merchandise and gravely declares that it has “wu.” But this wu is not Dick’s wu. In fact, the client clarifies that the item was made by a man who had suffered “great sorrow.” Clearly, the viewer must forgive Frank for his terrible decisions. He will transcend his own mistakes. At least his heart’s in the right place. He has wu.

When asked, in an interview with SciFi Pulse, how he wanted people to remember his adaptation of The Man in the High Castle, Spotnitz replied, “I hope it’s a show that stays with people. One that makes them think about the world they live in and appreciate that history is made by us. We can’t assume the good guys will win—and in fact, they won’t unless we fight to make it happen.”

It’s hard to imagine a statement less faithful to Dick’s worldview. Spotnitz’s versions of Juliana, Frank, and Joe, and their involvement in what Amazon persists in calling their “Resistance family” are the weakest aspects of his adaptation. Given Spotnitz’s convictions, they can’t just do things because they consult the oracle. There has to be a real reason.

Matters improve when Spotnitz and Amazon leave Dick behind. Consider the role of African-Americans—as yet unexplored but tantalizingly implied by their central role in the resistance—or the stiff, earnest, and sincere Japanese bureaucrat Inspector Kido, or most of all, Obergruppenführer John Smith. Smith, a high-ranking Nazi officer in the American Reich is, as far as I know, a Spotnitz original. He’s effortlessly charismatic, utterly watchable, and, at least in the first season, unapologetically ruthless. His family—wife, son, and two cute little girls—mirror the configuration on Father Knows Best, which is certainly no coincidence, and in their wholesome acceptance of the American Reich we recognize our country’s own history of genocide. Nice work.

Then, there’s Tagomi. Unlike Frank, Juliana, and Joe, he survives Spotnitz more or less intact, in part because he’s given less to do. In the show, he’s also the only character who consults the oracle. Well, he does once or twice in the first season. Then the oracle disappears altogether.

Tagomi is an odd character, and a key to the deepest themes in Dick’s book. Past middle age, a woolgatherer with a weak heart, Tagomi may represent an occupying power, and he respects traditions and conventions, but, Gnostic-like, he uses ritual to see the world around him clearly. During a striking moment in Dick’s novel—as the résumés of potential successors to Hitler are described to Japanese officials in horrifying detail—he has an attack of vertigo and suddenly knows:

There is evil! It’s actual, like cement.

I can’t believe it. I can’t stand it. Evil is not a view. He wandered around the lobby, hearing the traffic on Sutter Street, the Foreign Office spokesman addressing the meeting. All our religion is wrong. What’ll I do? he asked himself …. It’s an ingredient in us. In the world. Poured over us, filtering into our bodies, minds, hearts, into the pavement itself.

Why?

We are blind moles. Creeping through soil, feeling with our snouts. We know nothing.

So, Tagomi is trapped in evil. Evil is an ingredient in him and all around him. He blindly feels his way forward through the poured concrete of evil, without hope or direction. He has taken on a Gnostic view of the world. Not long after this passage he tries—again, blindly—to act against evil: he’s the one who fires that antique gun. The result leads him to seek new ways, new rituals, to wu.

And of course, it is a formless piece of silver jewelry by Frank that Tagomi holds and contemplates in the book’s climactic passage, which starts on a park bench. That’s when the wall between the false world of Dick’s novel and our “real” world is torn at last, and Tagomi finds himself—briefly and somewhat brutally—in our own 1962 San Francisco.

The park bench scene is replicated almost precisely at the end of the adaptation’s first season: Tagomi has been contemplating a necklace made by Frank that was left on his desk by Juliana. He grips it on a park bench, and abruptly, the screen blurs, then sharpens. A radio station plays “The Twist,” hot-dog vendors shout at customers under rows of American flags, and a paper with a Cuban Missile Crisis headline lands at Tagomi’s feet. It’s a wonderful moment, with precision that feels all the more surreal because, at last, it is dead-on familiar.

Readers of the novel who also watched the whole of season two know what Spotnitz ultimately did with Tagomi and our own version of 1962. Spotnitz laid out the overall story arc for that season, but he left the show after the fifth episode. Almost immediately, the writing and the pacing collapsed into conventional melodrama, and even John Smith became—Lord help us—likable. Still, somehow, Tagomi managed to carry on, in his neat little suitcoat, seeming to consult the oracle even though that oracle wasn’t in the script. He retains wu—at least the Spotnitz translation—and indeed, the word’s inclusion in a season one scene proves to be far from arbitrary. As Tagomi knows, evil is real, “like cement.” It covers everything. Suffering is the transcendent quality that allows Tagomi to move between worlds, bearing the novel’s legacy on his shoulders, a canister of film in his hand,

Turning, again, to 2017, we might consider what legacy and responsibility we bear. We won’t wake from some dream of Trump’s presidency into the “real world.” We’re here, and Spotnitz’s and Dick’s visions of the alterative past seem to represent two ways of looking at the actual present.

Spotnitz clearly believes that history is made by human beings, and that we can change it. We can uncover truth through our choices and our actions, and even blind action is better than no action at all. Find a Resistance Family. Be prepared to suffer—at least you won’t be trapped.

Dick, on the other hand, believes that we can’t change history. He also does not appear to believe that anything about suffering is transcendent. Furthermore, we’re always trapped, and we’re always blind. Admit this, and acknowledge that you can’t change history. History won’t budge. It’s not alive. Books are, sometimes. Find the right one, and consult it. You won’t change history; maybe you will change yourself.