Mark Thomas Gibson, Harsh Negotiations Over Land and Property in a Southern Dialect, 2019, ink on canvas, 48 x 70 inches [courtesy of the artist and Loyal Gallery]

Mark Thomas Gibson: Chaos Is The Season

Share:

When proposing this interview with Mark Thomas Gibson, I suggested the theme The Empire Strikes Back, an allusion to the necessity of finding the momentum to keep working after a perceived political success. As an artist who deals with politics in his paintings and graphic novels, Gibson has, over the last four years, produced a body of work about the corruption of individuals, ideals, and information. His book Early Retirement (2017) presents a recurring character, Mr. Wolfson, a prophet whose warnings of a coming fascist apocalypse go unheeded. When I visited Gibson in his Philadelphia studio this past May, we discussed the exhaustion that comes with prophesizing, the daunting inertia of Whiteness, and the burden of calling things as you see them, being right, and finding that—for the most part—nobody cares.

Mark Thomas Gibson: A few years ago when I had my first show in New York, I was really freaked out, or pissed off, [because] I had done all this research [in order] to have a very specific conversation around the Alamo. I wanted to talk about White victimhood, about the narratives that we keep telling. Like today, hearing about this “1836 Project” that Texas is going to do [“to promote patriotic education”]. That’s their counterpoint [to The New York Times’ “1619 Project”], to talk about the patriotic nature of Texas and its founding—which is not even hardly the story.

Will Corwin: I always thought Texas was a traitor state [in] the beginning?

MTG: They were a traitor state: a bunch of people who fled the [United States], who had debt, or had wives and families they left behind, or had other shit going on; they fled, and they were able to get land for cheap. They didn’t want to pay taxes on that land, so they pulled a kind of “taxation without representation” card, and they—all of a sudden—started to talk about their grandfathers or their fathers who had fought in the Revolutionary War, but it was just patriotism-as-land-grab—manifest destiny. It was the 1830s.

What I recognized in that show was that—at first, I thought what I needed, when I came out of school, were sales …. [I thought,] I need to eat, I need to pay rent, I need to pay bills, I need to pay for everything I have, and I don’t actually have enough time to make the work. I realized that I just needed to communicate. It pissed me off that I was not being asked to be a resource, to communicate that information [about the Alamo], nor was anyone interested in that level of communication. It was like Give me the elevator pitch and if I like the [gist] of it, or it feels like it fits inside of something I understand already, then we’ll go there.

A big part of what I’ve been thinking about watching this year [is] watching the revisionism, watching the memory get lost, watching the support of the government to help in that memory loss. Don’t you see the ruptures are getting larger? The weird plastering-over isn’t stopping the cracks. I’ve been thinking about the foundation of what this place is built on and whether you can build something on a foundation [that is] so fucked up.

There [are] a lot of people trying really hard to do the excavating around the foundation, to look at the base of it, to look at the history, to understand how things formed this way, so that we could possibly salvage the larger being of it and then uphold some type of constitutional morality that was somehow also baked into the pie. But, at the same time, there are a lot of other people just sitting there going, Lighten up, or [I’d] rather not. [They’d rather] just keep with the lie narrative of the 20th century, like, Let’s just think about John Wayne movies. That keeps getting at me, and I think it’s been noticeable just seeing the shift in art, [in] the art world, getting back to Let’s just not talk about politics, or Let’s talk about politics in a very obscure way: There’s a figure. That figure looks like this, so that’s political. And that’s it.

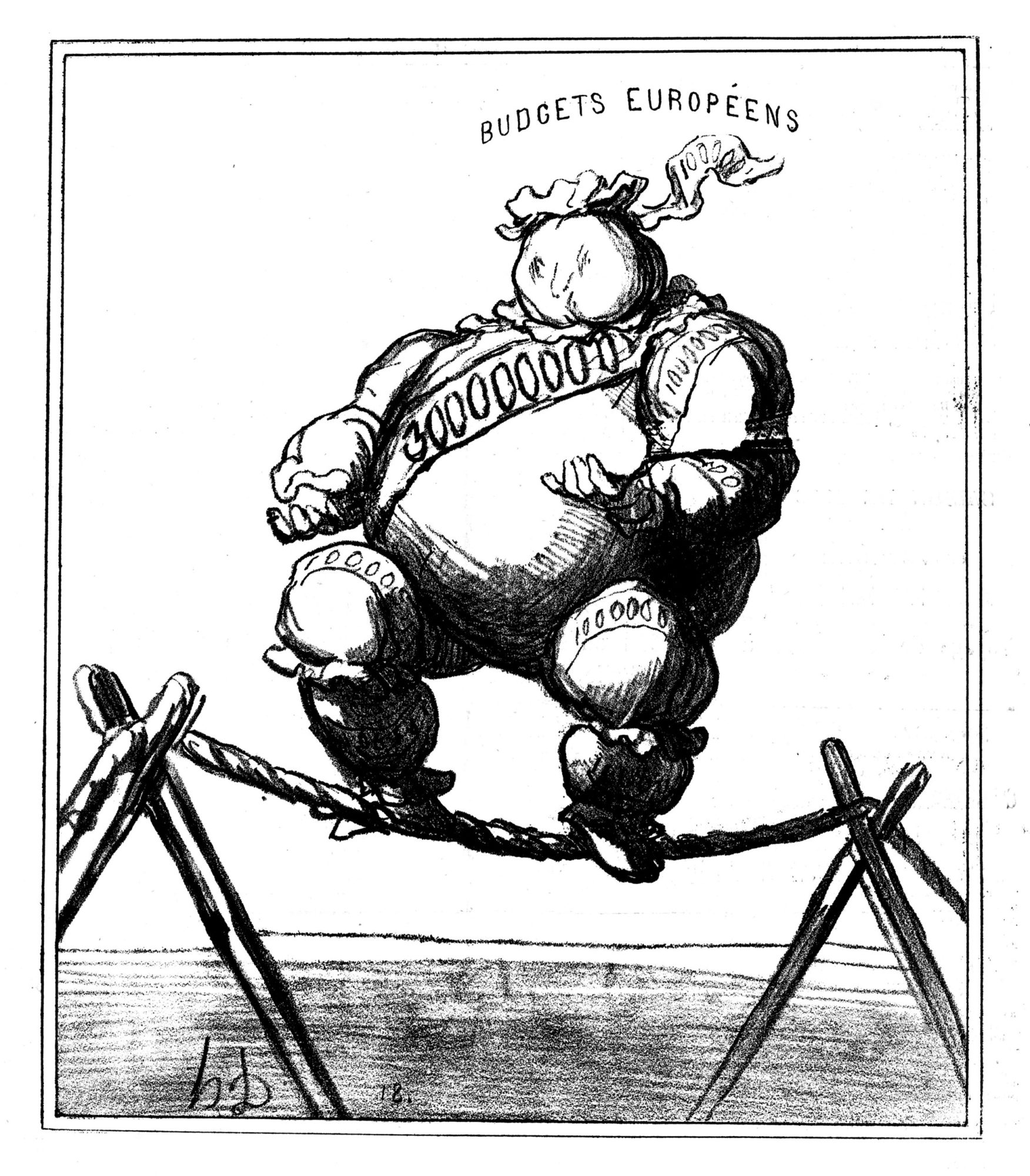

Honoré Daumier, Doucement!, 1868, lithograph on newsprint [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

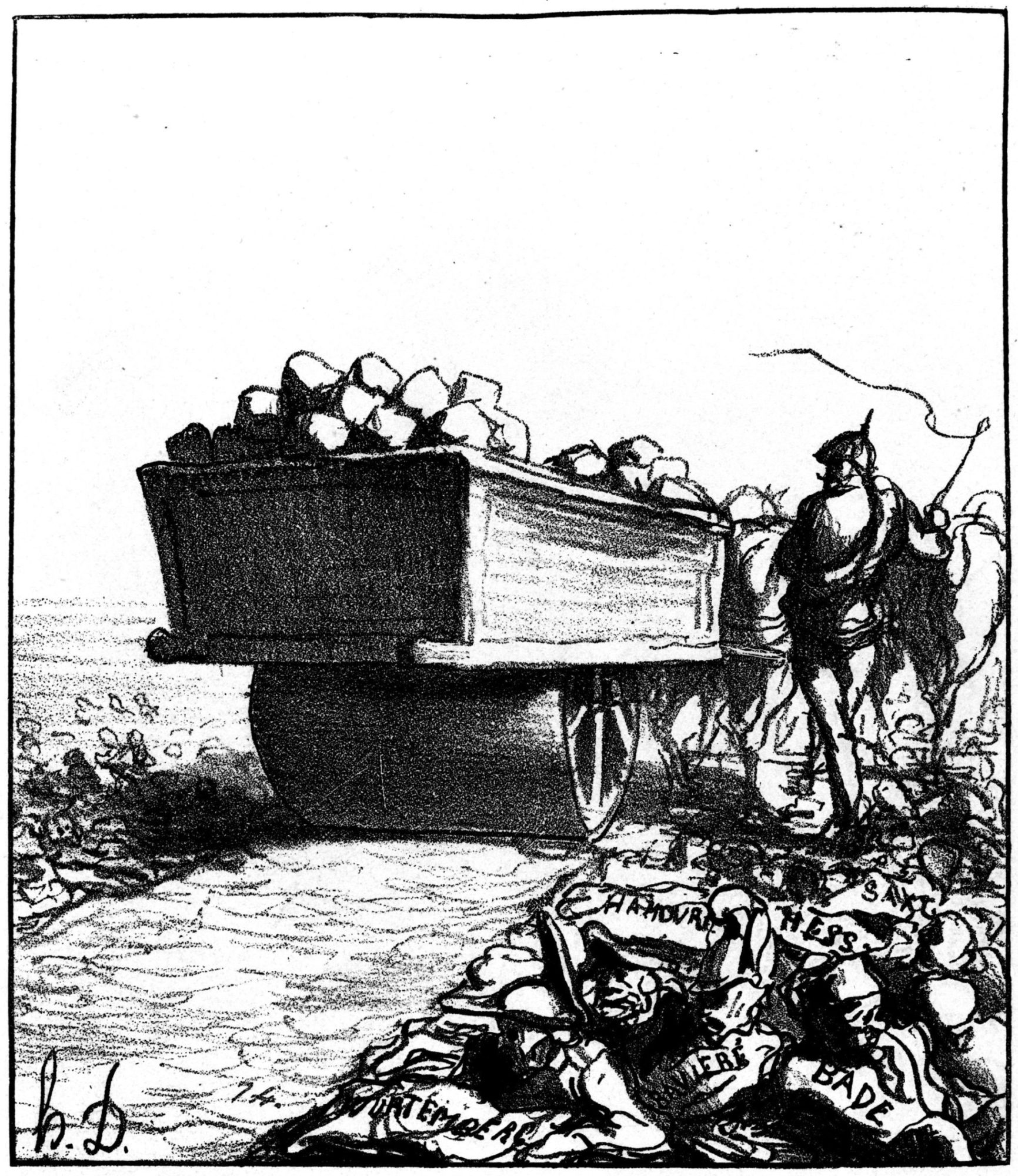

Honoré Daumier, L’unité allemande, 1870, lithograph [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and the Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund]

WC: I want to talk about the character you created for Trump in Early Retirement: the warthog.

MTG: I was looking at a lot of different stuff. I’m always looking back toward 19th century French work; looking at [Honoré] Daumier. I was looking at the patterns of representations of power, and [of] unjust power. It took me a while to draw [Trump] that way because … that’s the thing with caricature: Sometimes the person fits the mold so well that it’s like, how am I not thinking about this deeper? Is there something else underneath that I could bring to light?

WC: Did you try any other alternatives?

MTG: Yeah, like I tried different bird types, but it was like, no, they’re too sharp, there’s flight involved. He’s not a penguin, he’s not a wobbly penguin. He is a hog. Yeah. It’s a hog-man. It’s something that roots in shit.

WC: It made me think of those Star Wars characters—

MTG: —Yeah the Gamorrean Guards, that kinda thing. But I wanted him to be so large that you’d walk into a room and he’s taking up a whole bed, similar to Jabba [the Hutt] in that way. Because he is a tall man, and [some people, in his presence,] would probably be impressed by his scale. They’d be impressed by just the size of his head; the size of the hair; the size of the suit, you know? As a tall person [myself], my father used to tell me that “You’re going to give off a certain energy that other people are going to take in because [of] your scale. They have to contend with it.” With a body like [Trump’s], that exudes a boorish attitude he’s aware of it. The book has a lot to do with the idea of prophesizing, and being the crazy person, and being the one who sees it as it is, and trying to tell everyone, and not being heard.

I’m not an activist. I’m an artist who thinks about politics. But there’s a type of labor and work ethic [that organizers have] that I do not … and I would never want to take that from them or want to glom onto that. I find [that] when I’m doing the work, and when I’m making things … the politics of it, the drawing of it, the motion of it, the absurdity of it—it does feel like channeling sometimes. It does feel like I’m saying something, and I’m calling a shot, and people are like, Yo that’s kinda dark, and that’s kinda weird. But if you don’t see that history occurring, if you don’t hear the demagoguery, if you do not see that [Trump] is taking you down this road, then you’re slowly ticking toward [fascism]. You’re not calling it out. When everyone’s using phrasing and language that was used in the Holocaust to describe the impending doom that’s possible in this moment. When people are saying, “First they came for…,” that whole storyline. When [survivors of fascist regimes] are telling you that this [time] reminds them of something, and you still do not listen to them, you are being callous. You are being cold and dry.

And that’s the thing. When a [callous] person is in power … it brings out callousness in other human beings. People are saying [racist, hateful] things, and they’re feeling emboldened, and [those] people are not being checked on it. And the left is checking themselves while not checking the other side, like everyone is counterpunching the wrong thing. I’m seeing these things, and I have to make something about it. So when I originally started to form that story [for Early Retirement], I was thinking a lot about utopias.

Mark Thomas Gibson, The One Where Donald Trump is a Hoarding Dragon, 2019, ink on paper, 59 x 125.25 inches [courtesy of the artist and Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery]

WC: Like which particular utopias?

MTG: I was thinking about starting off with Sir Thomas More. Then rereading [Utopia (1516)], and going, wait, slavery is a big part of this utopia. I’d totally forgotten from reading that book when I was younger. It definitely started [me thinking about] what it is that people want, and how we all have different perspectives on different needs. It’s imperative that we come together to have conversation so we can understand what those wants and needs are, and we can argue as to why slavery is not a great idea. It seems like, for many, it would be an easy thing to say, That’s a bad idea. But we also realize that there are people that need to be walked through it. Because if we do not do it, if we say, I don’t like to talk about these things, or, Oh, I don’t really want to get uncomfortable about these things, or, Oh, just move the work, instead. … Someone’s going to give an opinion, someone’s going to historicize it, and they may do it in a way where you are going to be the next victim.

I’ve [been] around White people my entire life. There’s this lack of introspection … about [their] actions, or [their] history and [their] culture …. That’s infuriating because you’re like, Well, I’m stuck holding this bag. Some people are like, Fuck it: I ain’t holding this bag anymore. I’m 41 now, and I’ve been going to talks, performances, and readings since I was in second grade. I’m tired of … singing the Black national anthem to a group of White people, who will never remember the words, or [else] doing some type of outreach work trying to bond people together, or [else] working inside of the school system. What I would always see, almost immediately, once the program had served its purpose from an optics point of view, [was] that anybody who was there in a place of power doesn’t give a crap. The next action, almost within a breath [snaps], will be something along the lines of reinstituting the structures and the power systems that were there.

WC: So in the post–2020 election feel-good moment, how do you recalibrate your … Trump narrative? How do you re-spin that narrative so that it deals with the more [infuriating] fact that people are relaxing? What’s the next step?

MTG: Yeah, the Biden years are something that I’m thinking about …. There’s still stuff that’s going to go on, like you might get a pipeline canceled here, but we are still [filling concentration camps] at the border and not talking about it in a real way. It’s kind of whatever irks me, and I’m always going to be irked. I think that’s the thing about being a curmudgeon.

Mark Thomas Gibson, White Flight, 2020, ink on canvas, 66 x 88.75 inches [courtesy of the artist]

WC: So you own your curmudgeon-ness?

MTG: Oh, fully! During this presidency, I’m still looking, and I’m still noting what’s going on, and I’m still thinking about the bigger projects of what’s happening at the moment. I think it played very well into what people believe [about] who I am, or what my narrative is, when I was attacking the Trump administration, because it fits into a binary kind of logic. But when you start to question, let’s say, what you’re going to do, or what’s going to happen, or what’s not going to be accomplished in this [Biden] administration—

There are things that are on the table right now. We could [contain] the powers of a president. Like Andrew Jackson, when he changed the authority of the president and went against the [Second Bank of the United States], and overstepped a lot, people were like, A president’s not supposed to do this in the executive branch. But … no one ever gave that power back. And presidents [rarely] ever give the power back that the previous [president] gained. And that’s so scary. If [Biden] were to step up and say, “You know, there are certain loopholes here that a president should not be able to use. A president shouldn’t be able to hide this information, a president shouldn’t be able to do this, a president shouldn’t be able to do that,” then we [would] really have a shot. But no one’s going to give up that power.

In [Daumier’s] war works, he was talking about when the ruler comes in. We [the public] are like, “Oh great, reform, or change.” And [King Louis Philippe I] was like, “We have a little war we have to take care of.” And [they were] like, “War, that’s horrible, but let’s do it.” Then [King Philippe was] like, “There’s another war.” And they’re like, “Okay another war—why are we doing another war? Why are we doing this other thing?” Then, by the end of it, they’re like, “The king is garbage.”

But there will be this continuation of power and what power does in this country, because of how [power is] formed, how we respect it, what we respect in this country. I haven’t sat down to prophesize where I see this thing going yet. I just see a lot of sitting on hands and waiting out a clock. Pretty much by August if a lot of this legislation [voting rights, infrastructure] doesn’t pass, and it isn’t really being moved on, it ain’t happening. We’re about to go right into an election cycle. We’re in limbo. We’re not in a space of joy, and praise, and happiness.

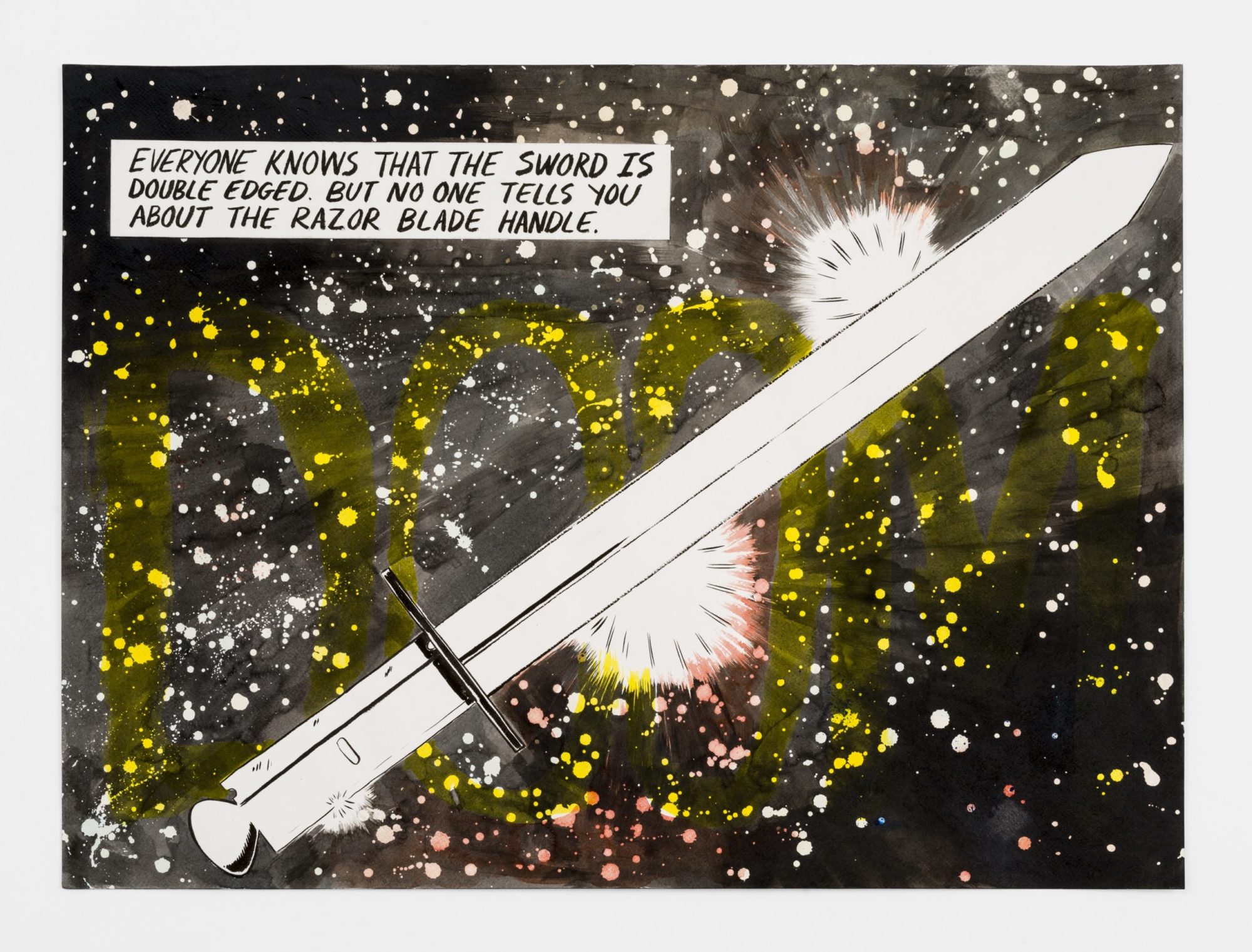

Mark Thomas Gibson, The Razor Blade Handle, 2020, ink on paper collage, 22 x 30 includes [courtesy of the artist and M+B Gallery]

WC: The work in Stockholm [American Psyche at Carl Kostyál Gallery, June 11 through July 11, 2021 ]: Do you think it will read well to an audience in Sweden?

MTG: I hope it does …. I was thinking about the idea for a show about this black Pegasus, a creature that’s captured—maybe it’s me—and [trying] to capture this idea of being seen, being witnessed, being dragged into a situation where you’re asked to perform. You’re doing these things and you’re being manipulated for the pleasure of others, and then—all of a sudden—you’re released back into the world. That thread could speak to slavery, it could speak to education, it could speak to other forms of institutions.

WC: It could be the art world?

MTG: It could be the art world. It could be a lot of things where I feel like, in my life, I’m asked to be, or asked to perform, or asked to participate. And then at the same time, how do you stay in your head? And I think that part of the story, or the part of the visual narrative of the story, is that I always wanted to be the face of this character [the Pegasus]. There’s always the eyes. The eyes are what’s telling you what’s going on inside of this character, so that we can connect to that character, so that it’s not about Uncle Sam. It’s not about the other people inside of the narrative [depicted in this cycle of images] it’s about this humanity, it’s about this body.

I recognized when I was making Early Retirement that all of us have our different associations of what we think is a good life, and the only way we’re going to actually get by is if we have the conversations. We have to, because I know that I might have some politics that some people will say are crazy. Then there will be someone else, and I’ll be like, “Whoa, I can’t go that far, bro.” What you do is you develop that friendship on those other things that you have [aside from politics], and then—all of a sudden—you can bring in this other part where the friction is, and there’s a little more trust, and a chance to have maybe some understanding on some things. But if the whole policy of the culture and the structure of what we’re living is all about creating wedge issues that cannot be described, cannot be worked out, or cannot be really talked about, [then] they’re just there to separate people.

We have to then be conscious of how we un-wedge that.

Will Corwin is a sculptor and journalist from New York. He has exhibited at Clocktower, La MaMa Galleria, and Geary gallery in New York, as well as in London, Hamburg, Beijing, and Taipei. He writes regularly for ART PAPERS, The Brooklyn Rail, BOMB, artcritical, and Canvas—and formerly for Frieze.