Making Time: Mildred Thompson’s Magnetic Fields

Mildred Thompson, Magnetic Fields, 1991, oil on canvas, triptych, 70.5 x 150 inches [courtesy of The Estate of Mildred Thompson and Galerie Lelong & Co., New York]

Share:

Color, line, form move toward an undefined but perceived center—by moving out of it. Density builds, decimates, then replenishes. There’s a knot threading.

Ten feet? Twenty feet? The implication is forever. Blue anchors and guides the eye. The yellow is a blanket. It is the proper height, density, and protrusion in relation to the floor. In relation to the ceiling. In relation to the body. In relation to space. It floats. It sings. It stills—although it won’t stop moving. The blue is nearly sublimated, though I see it threading through. Is there a barrier hidden? One may not want to evoke volatility. Or ruse.

The painting expands. It contracts. It’s breathing. The lower right side of the painting looks edible, looks, specifically, like I can eat it. Here’s a flaunting of Wayne Thiebaud. There’s a shadow visible along the bottom of the painting—otherwise one might think it recessed into the wall. The image feels apportioned. Dissevered. As if I’m only getting a glimpse of something. The layering of color and line gives the impression of the minutiae of an idea and the audacity of one grand statement. The painting is immersive. Subversive. It’s disarming. Grind these colors to a pulp. Put them out in the sun (or moon) for 800 days and you get Rothko. It’s too easy to say that Thompson’s painting dazzles.

It does. Of course. But what else does it do? Every time I look up at it, it’s teeming with light. Energy. Tune. If I had to reimagine it as sound, it would be Oliver Nelson. Thelonious Monk’s “Nutty.” Billie Holiday—“I Loves You, Porgy.” Earth, Wind & Fire’s “In the Stone,” Prince’s “Erotic City,” even Van Halen’s “Jump.” There’s that lyric from “Life Can Be So Nice,” when Prince confessed “no one plays the clarinet the way you play my heart.” Yeah, totally.

I see a memory board, a Lukasa, transmitted to me from the Luba of the Congo. And the mind work of African fractalism. Bit by bit. Part by part. The fractal complicates things. How to gauge tactility? The imagery winds around itself like a tightly wound clock, but there’s a spring out of place. Depth isn’t given means just by linework, but also by the expanse of yellow burrowing and laying waste. Upending time. Keeping rhythm. Brandishing light. This painting is redolent of night vision. I keep coming back to the blue—cobalt/cerulean/turquoise—conferring. Not just any blue—celestial. From a distance I hear sparks. This is a global union.

There’s plucking. Those three dollops of burnt orange in the upper left pose a threat. Not pose a threat—stage a coup. Not stage a coup—a coup de grâce.

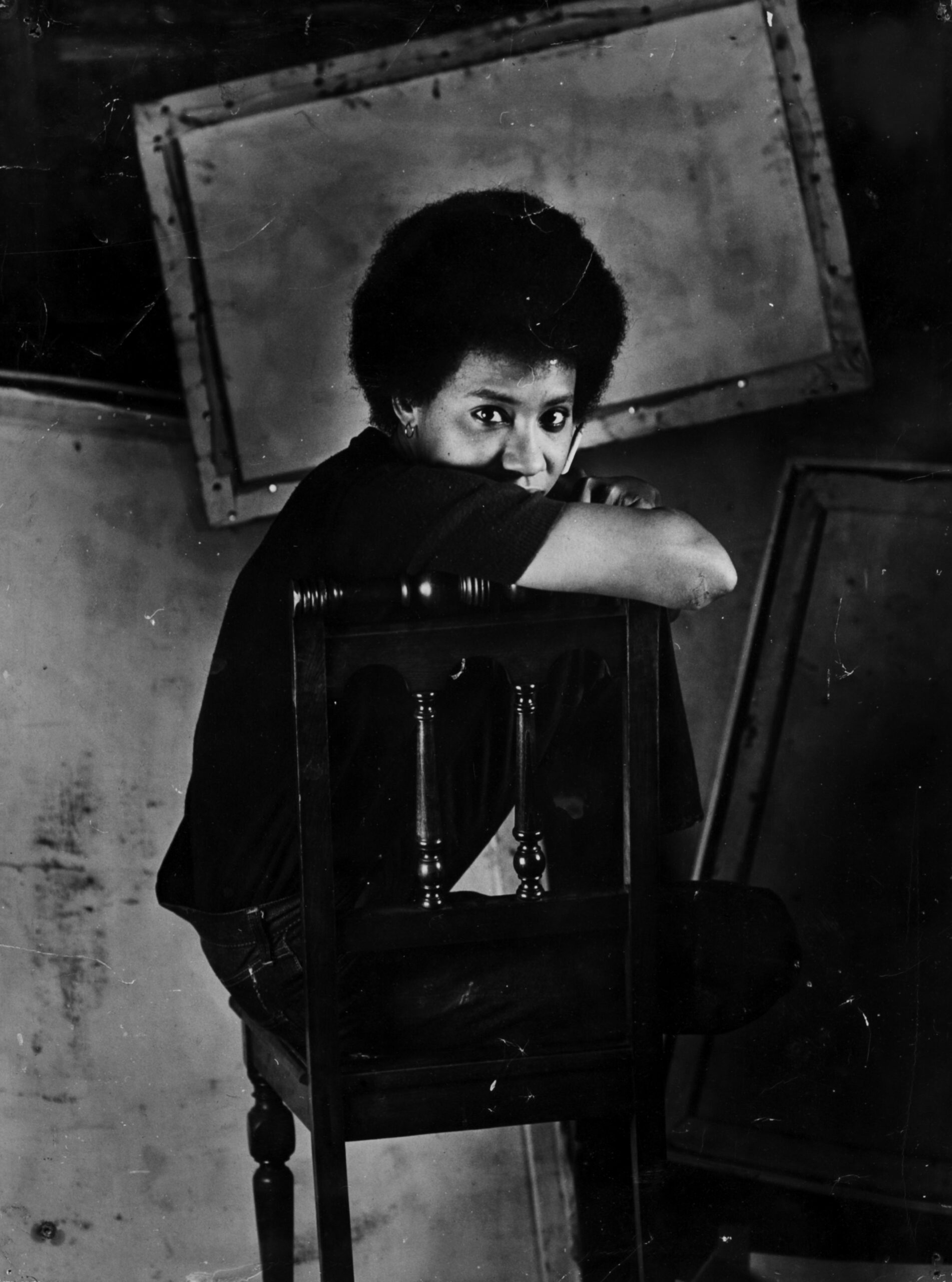

Mildred Thompson, c. 1995 [© The Estate of Mildred Thompson; courtesy of Galerie Lelong & Co.]

Not “strike of mercy” but an annotation of colors materializing then rebelling. Annotative to sound. This painting surges. I feel its energy. I look, and it’s as if I’m seeing it for the first time, each time I look. Systems building. Thompson has dared to align space, to make it a compendium. The painting moves closer to me. I jump into the eye of a storm—the seed gate. I can hold the painting in my hand or let it envelop me. It can signal, me, while I truncate hope. Unearth this thing. Crystal. Fuming. Scope. Incision.

Think of the painting in relation to Figure (11th–17th century). Mali, Niger Delta region—a seated terracotta figure with its arms folded across its knees, head bowed. The knobby statuette could be a visitation tweaked from Magnetic Fields. At midday, or, say 3 pm, light leaps out of the painting in wide shafts. Light holds there. In the morning it glows. Soon it will crest. The paint is built up in dense patterns. Mildred Thompson allows us to see each layer—portions of which still look wet. Fuchsia operates in counterpoint to a vortex. The mode. What looks to be an impasto technique hacks away at the image while loading it up. There’s “pudding” in spots. A world is sliding. One’s sense of perspective and delineated space yields to a kind of armature. Thrust. Yields to thrust. It’s certainly magnetic. The colors hold on for dear life. Drawn in. Discs slicing the plane for life to walk through. Rounding out space to make it bend. Are these molecules? Eight slashes of pure green. Plowed. Defiant. The brown is a hex. I’m experiencing it frontally, but also through a concave flux. Sideways, stretched.

I can’t wait until night hits. I think it makes the heart ache. Ignore the seams of the three panels segmenting the image—divulging that there are three canvases at stake. Left. Center. Right. Viewers complete the frame. We lay on top of it. We’re pulling out all the ribbon. Slash. Brick. Splotch. Path. A circumference. An interior. A tell—the mound formed by the accumulated remains of ancient settlements. Is the light dimming? The colors never muddy. I always locate my body in terms of its space. Cessation never enters the frame. Something’s swelling. I see faces and planets and rifts. I wonder where she began. There are bridges that turn into daggers. Whole synths as hybrid. Synth as programmatic sound. A reverse culture. Spinning. Torque. Durational. A statement on time. Shields. Inner space.

Mildred Thompson, Magnetic Fields, installation detail, 1991, oil on canvas, triptych, 70.5 x 150 inches [photo: Caroline Philippone; courtesy of The Estate of Mildred Thompson and Galerie Lelong & Co., New York]

Mildred Thompson, Magnetic Fields, installation detail, 1991, oil on canvas, triptych, 70.5 x 150 inches [photo: Caroline Philippone; courtesy of The Estate of Mildred Thompson and Galerie Lelong & Co., New York]

I think the gesture—line—is continuous. Each one. What I thought were hatch marks is actually a clustering or spray. Linework compiled of dashes, swirls, circles, pathways, cubes, dots. Let me come back. A red, red rectangle just popped out at me. Then it turned pink. The painting floods the entryway with light. With life.

I saw Mildred Thompson’s painting Magnetic Fields at the Menil Collection. It hangs near the museum’s entrance. I visited the painting over the course of three days and sat with it for hours. Standing in front of the painting, up close, I see now where she emerged. Abstraction is a refusal. Light is always present. Emanating, diffusing. Movement is an expulsion of form—disintegrating, galvanizing, igniting—out, out.

Sherae Rimpsey is an artist and writer. Rimpsey is the Mildred Thompson Art Writing and Editorial Fellow.

The Mildred Thompson Arts Writing and Editorial Fellowship is a collaboration between Art Papers and Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane University. Funding for the two-year editorial position was provided to Newcomb Art Museum by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for an emerging Black arts writer/editor to gain hands-on experience as part of Art Papers’ editorial team. The fellowship also honors and builds upon the legacy of Mildred Thompson, associate editor of ART PAPERS from 1989 to 1997.

Conceptualized as part of Art Papers’ Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility efforts, the fellowship received seed funding from AEC Trust and The Homestead Foundation to pilot the program in 2022.