Luftmensch

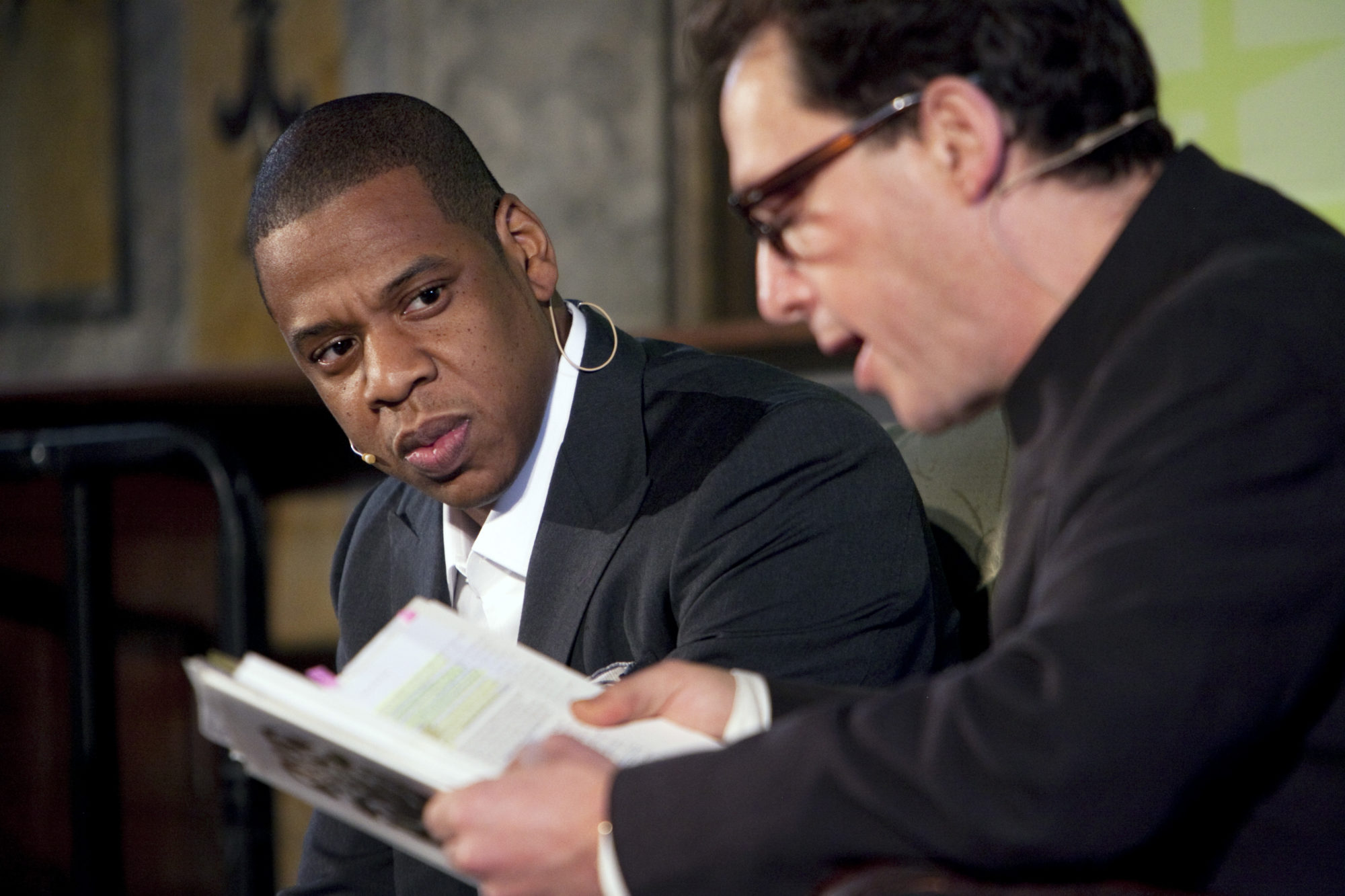

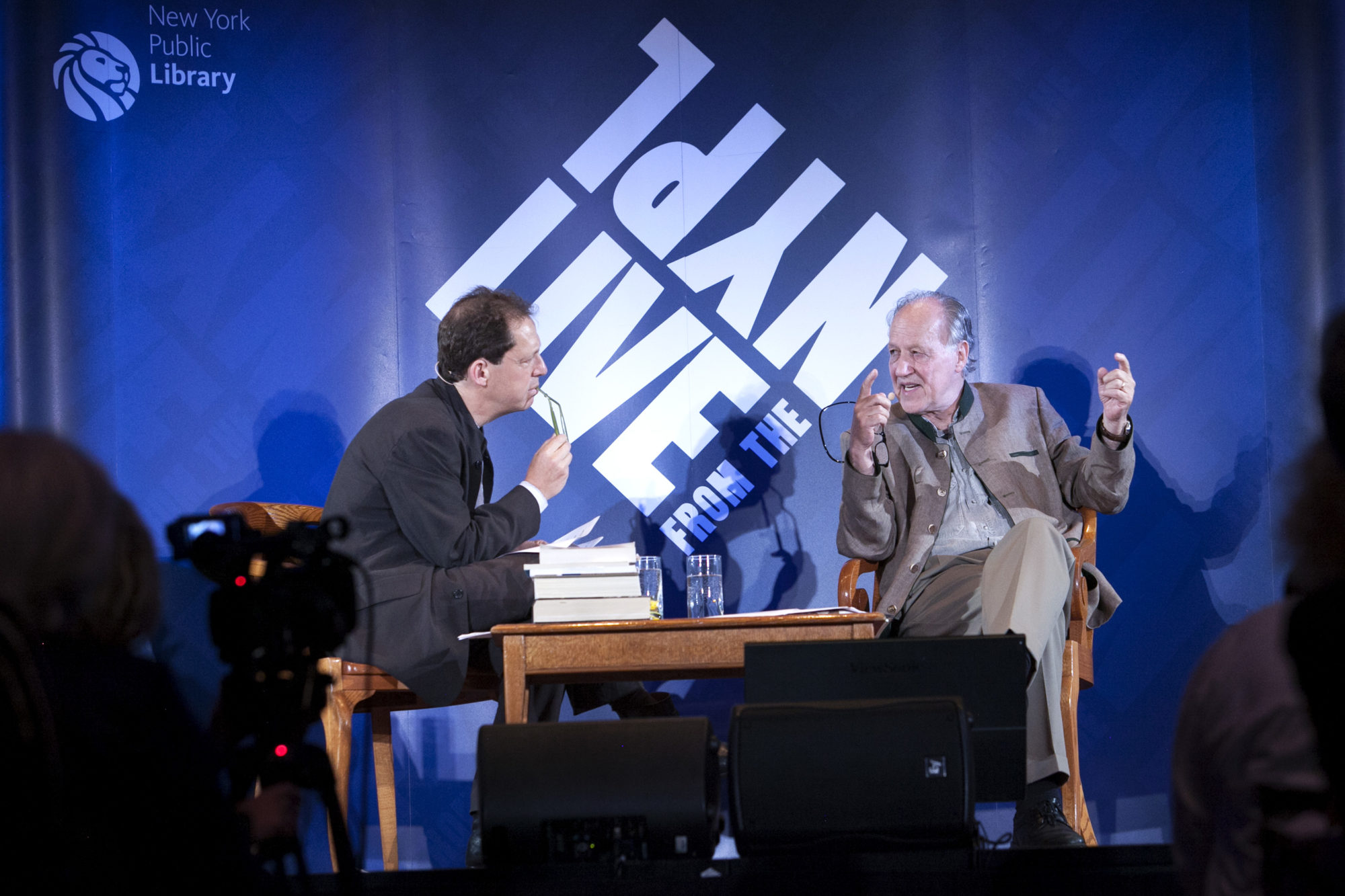

Paul Holdengräber at LIVE from the NYPL [all photos: Jori Klein; courtesy of the New York Public Library]

I have personally seen Paul Holdengräber perform two public dialogues in front of packed houses: one with the painter Anselm Kiefer, and another with the composer Philip Glass. Public discussion — in the agora of ancient Greece, atop soapboxes on city street corners, in debate societies, churches, and lectures halls — has always been a part of Western society; Holdengräber's events are a mix of This is Your Life and a cross-examination.

Share:

Holdengräber has interviewed in many capacities and through many media (on YouTube, in museums), and he’s interested in engaging everyone affecting culture (Patti Smith, Mike Tyson, Werner Herzog, JAY-Z) in conversations presented in an interactive public forum. In his previous position as founder and director of the Institute for Arts and Culture at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, he sought to challenge the notion that museums are “mausoleums” by addressing real audiences with current and in-progress ideas. Now, as director of public programs at the New York Public Library, a role he conceptualizes as “Curator of Public Curiosity,” Holdengräber is not merely in step with the gargantuan institution, but perhaps personifies it—a place second in national scale only to the Library of Congress, and headquartered in Carrre and Hastings’ landmark building, where “LIVE from the NYPL” takes place. It is not surprising that public programming at the NYPL would be voracious for data, with probing questions informed by a seemingly bottomless well of research; under Holdengräber, however, these incisive conversations may well break into French, Latin, or Yiddish quotations, or sometimes into song (or dance with RuPaul). His interviews are sometimes staccato but profoundly enlightening (Kiefer), at other times heartwarming and mellifluous (Glass), and they always confer a sort of cultural authority as he welcomes guests (prey?) into his bookish Bryant Park lair—and onto the NYPL’s popular live-streaming channel. We tasked the person who asks all the questions with answering some of ours.

Paul Holdengräber interviews Patti Smith for LIVE from NYPL

Will Corwin: So, how did you end up being born in Texas?

Paul Holdengräber: My parents were born in Vienna. My father left on the last possible day you could leave Vienna, on the 15th of June, 1938. He emigrated as a medical student to Haiti, where there were a few Jewish families. He became a farmer and grew vegetables.

WC: Was Haiti particularly inviting? Why did he end up in Haiti?

PH: Haiti was not particularly inviting. The “why” presupposes agency; it was luck and chance—there was no quota on Jews. There were a few Syrian Jews but there wasn’t much of a community, a few families. He met my mother while playing chess with my grandmother. He would give her the remains of the day—the vegetables that he hadn’t sold or that he’d kept for the Jewish community.

They married when my mother was 19 and my father was 25; they were married for 71 years. My father had wanted to come to America, but couldn’t come for all kinds of reasons that are less glorious in terms of American history, and he ended up in Mexico, where my sister was born. Because of certain medical conditions that I had before being born, he decided two things: “I didn’t get to America,” and “hospitals in Houston, Texas are very good.” “So, I’ll have an American son.” I spent four very important days in Houston, the memory of which is slight, and most people don’t tend to think I have a very Texan accent. But I have an American passport.

WC: Had your mother seen a lot of tragedy in Vienna, or was she too young to remember anything?

PH: She was 14, so she had seen enough to know it was terrible and to never, ever talk about it. But she transmitted the trauma. When the Austrian government, through the Austrian president, awarded me with the Austrian Cross of Honor for Art and Science—a funny thing to give a cross to a Jewish boy—I said to my mother, “I don’t think I should accept.” She said, very firmly, “Be gracious, don’t mention the unpleasantness, and my story is not yours.” Which is quite something.

WC: My story is not your story: is that the crux of interviewing?

PH: I say, “I’m the curator of public curiosity.” I’m the midwife. When you are in the audience, you are hopefully an interested listener. In some ways, you [William Corwin] want to be in my seat—or maybe you don’t want to be in my seat, but you imagine what you would have asked. But my goal—as I did with David Lynch, Ed Ruscha, JAY-Z, Zadie Smith, Patti Smith, or Philip Glass—is to represent the audience as best as I can, their interests and curiosities. The question that I’m trying to phrase is—I’m hoping—the question that the audience as a whole, and some people in particular, may have.

JAY-Z and Paul Holengräber

I try to be the spokesperson of a general interest that perhaps many people might have for that person. I try to create a common humanity.

– Paul Holdengräber

WC: When you call yourself the curator of public curiosity, it strikes me as a fascination with difference as opposed to similarity. Are you trying to draw the audience into a kind of empathy with the speaker, or are you trying to exhibit the beautiful mosaic of humanity? To make it sound very prosaic?

PH: It reminds me of a Woody Allen line. He said, [more or less,] “I’d like to leave you on a positive note. Will you accept two negatives?” Maybe it can be both. Namely, when my mother said to me, “my story is not your story,” obviously her story is part of my story, but I also have a story. I need to have a voice, and in a sense what I’m trying to get to is my own voice. The origin of the word infant literally means not to have a voice. An infant is someone who doesn’t yet speak, who doesn’t yet have the gift, or the curse, of words. I try to allow for both.

Many people have remarked that the conversations they like best are conversations with people who have nearly no similarities with me. When I speak with Mike Tyson or Pete Townshend or Harry Belafonte, what do I know about so many aspects of their world? I try to be the spokesperson of a general interest that perhaps many people might have for that person. I try to create a common humanity.

I do love certain occasions I’ve had of speaking with people I feel I’ve known forever, even though I’ve only met them two minutes before going onstage. A perfect example of that would be Edmund de Waal. I read The Hare With Amber Eyes. It was a story that naturally struck me, and the whole background of Paris and particularly Vienna, the background of loss and collecting [presented] issues which interest me greatly. When I met Edmund onstage, the line from Baudelaire’s poem Spleen came to mind: “I have more memories than if I was a thousand years old.” I felt I had known him forever.

When we fall for someone, and perhaps even when we fall in love, it is itself so interesting because to speak about the strongest emotion is to speak with the language of vulnerability. We end up trying to find similarities in language to express what we feel, and I think that the people we love are the people whose adjectives we share.

WC: You studied philosophy, and that made me think of Socrates—that information is transmitted via dialogue. Do you ever think, “I would rather listen to this than see it written down,” or “this would be much better as a text than it would be spoken aloud”? What do you think about word versus text in the context of dialogue and ideas?

PH: Yes, I believe deeply that we come to thought through words—thought is made in the mouth, or some such sentence from Tristan Tzara. Philosophy, as we believe it to be, started with a conversation. I don’t particularly think about how it will play itself out when written down. I think there’s such a difference between the written word and the spoken word. Some people speak in paragraphs; I don’t know what I speak in— I suppose my claim to a profession is to make other people speak, to find a way of giving them words and to find a way of bringing about a thought. I feel that through speaking we can discover ourselves. Not dissimilar is the word autobiography: auto-bio-graphein. It literally means “the life coming-to-be through its writing”; so, the self coming to life through writing and discovering itself through writing. Some people discover themselves through writing, if we consider literary history, from Rousseau to other great people who wrote autobiographies.

Paul Holdengräber interviews Laurie Anderson for LIVE from NYPL

WC: Do you think you’d lose too much if you wrote down all the discussions you’ve had? Or would you gain something?

PH: I suppose things would be lost. It’s also the incredible value I put on the evanescent, scripta manent: words remain. Nevertheless I’m pleased that Lorin Stein asked me to interview Adam Phillips, the first psychoanalyst to feature as a subject inThe Paris Review [Spring 2014, No. 208]. I am thrilled that this interview found its way into print. I spoke with Adam for over 10 years, much like an analysis itself, you might say. After 10 years of ongoing conversation, I don’t think there was much choice besides [publishing] text! I was extremely happy when Adam, of all people, as a psychoanalyst, said to me: “For the first time, I have said what I mean.” He recognized himself in the written word which had originated verbally.

WC: So, what is your training?

PH: I studied at the Catholic University of Louvain, which is famous in the world of phenomenology and neo-Thomism. Why phenomenology at Louvain? Because it rescued Husserl’s archive from the Nazis. Why neo-Thomism? Because it has Saint Thomas Aquinas’ archives. So it’s a mixture between the Middle Ages, the birth of phenomenology, and the background of existentialism. I studied with some of the most extraordinary philosophical minds of that time. After Louvain I spent some years in Paris, and those were the years when I would have classes with Roland Barthes, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Vladimir Jankélévitch, and Michel Foucault. It was the late 70s, and they were all there! Barthes was killed a few months later, while crossing the street, by a laundry truck.

I remember Foucault writing a letter of recommendation for me for Princeton, saying—it was about two lines long—”the premises of Paul Holdengräber’s work on European nihilism”—which is what I was interested in then, and the only reason I know I was interested in it then is because I see that letter still in front of me (I have to find it)—”seem to me, solid. Michel Foucault, Chair of the Systems of Thinking.” I came to Princeton, and went to graduate school in comparative literature.

WC: Did you ever imagine you’d end up “curator of public curiosity”?

PH: It happened by buona fortuna. I suppose in philosophical terms, “The owl of Minerva will take its flight at dusk,” and “retrospectively there will be illumination.” My parents did wonder, when I was having great difficulties in school and being rather impish, rebellious, and a smart aleck in one form or another, “What could he do?” My father and mother always thought in some ways I had the makings of an impresario.

Paul Holdengräber interviews Elvis Costello for LIVE from NYPL

WC: Considering that your family were unintentionally nomadic—since it wasn’t their choice to leave Vienna, and then move to Haiti, [to] Mexico, [to have] a brief stopover in Houston, Texas, and then [go] back to Europe—I have two questions. Are you still a nomad? And besides “impresario,” what did they actually expect from you?

PH: I feel I should lie down on a couch! What a complicated question. How can I respond?

WC: Let’s break it down: are you still a nomad?

PH: I love the way you defined this restlessness: an unchosen nomadic world. Yes, my parents left [Vienna] at the last possible moment, and yes, that created a kind of restlessness in them. We moved around a lot. I am surprised sometimes at myself, given how much we moved around when I was a child, how little, comparatively, I travel now that I am older. The way I travel is through words and through other people’s lives. As if visiting other countries, I visit other landscapes by speaking to people who tell me their stories. I think about home a lot, and I think about exile a lot. Edward Said said, “exile is strangely compelling to think about but terrible to experience.” And so in a roundabout way, but without further delay, I can’t say New York is home; I can’t say that I have a home. I know what it means for other people. It does mean to some extent that I could pick up and go. It does feel that I don’t quite have any attachments. I think the attachments come in the form of people whose adjectives I share, people I love.

WC: And the expectations?

PH: What did my parents want for me? When I began studying law and philosophy, I think my father was hoping for a while that law would stick. It didn’t, and I started to become, not a philosopher but someone who studied philosophy. There’s a Yiddish word for someone who may not be terribly grounded. It’s a beautiful word: luftmensch. Luftmensch means someone who has his feet firmly planted—in midair. There’s something of an untethered balloon in me.

LIVE From The NYPL

Luftmensch means someone who has his feet firmly planted—in midair. There’s something of an untethered balloon in me.

-Paul Holdengräber

WC: As refugees, was it possible for them, after their life experience, to ever actually have a concrete expectation for anything?

PH: They wanted to do well, and they wanted not to be hungry. My father’s one regret in life was that he didn’t become a doctor. Haiti didn’t have the ability for him to become a doctor, and by the time they reached Mexico it was simply too late. He had a family to support. He also had his mother and father-in-law, and his own mother and father who had escaped to London, to support. He had sit-downs with me, usually much too late as fathers do, telling their sons about the bees and the whatever-it-is. The conversation was: “You’re going off to university. Don’t forget that the word university comes from the word universe. Don’t forget that the more interests you have, the more interesting you are.” I’m not sure about that one. And lastly [he said], “Paul, don’t only study the soul from a philosophical point of view, but cross the street.” By that he meant go from the philosophy department to the anatomy class—the philosophy department was across the street from the medical school at the University of Vienna, back in his school days.

WC: Did you do that?

PH: If I cut my finger opening an envelope, I nearly faint. I cannot look at blood, and therefore I never crossed the street. But I did cross the street in other ways. That is what I do.

WC: I know that one of your regular conversation “gigs” is with Werner Herzog.

PH: I speak to him at least once a year to remain sane ….

Paul Holdengräber and Werner Herzog

WC: In your NYPL discussion with Anselm Kiefer on May 4 [2017], you pointed out the similarities between Kiefer and Herzog …. Then, reading your interview with Herzog in Brick magazine [Winter 2009, No. 82], I realize there’s a strong relation between Herzog, Kiefer, and yourself. Your lives were shaped dramatically by the same dramatic historical events of WWII. Do you feel a relationship or even a kinship with Herzog and Kiefer for that reason?

PH: My trauma is a secondhand wound; it’s a transmission of trauma. The [words] transmission and tradition are the same in Hebrew: they [translate to] “what is passed on.” So I’m living with the memory of something I never experienced, the memory of something I don’t know. I was inspired by Nathalie Zadje, a psychoanalyst who studied transmission of trauma from the point of view of certain émigré cultures, particularly in North Africa, and how different that transmission is in different cultures. She studied how trauma passes from one generation to the next. But I grew up very obsessed with the Holocaust, very obsessed with my parents’ history, maybe in a way that was unhealthy. I do think that my interest in Edmund du Waal, Werner Herzog, Anselm Kiefer, and Claude Lanzman all comes from the way in which the world was transformed, changed, and to some extent destroyed. When Jonathan Demme invited me to speak to him about Fahrenheit 451, both the Truffaut movie and the Ray Bradbury story, the burning of the books brought back memories that I don’t have.

WC: Did this trauma, both the tangible and intangible aspects, impose a distance on you and your family as well? Is that another commonality with Kiefer and Herzog?

PH: You were there for the Kiefer night. I think my questions to him about that were pointed, and I tried to make the comparison with Werner Herzog—the whole notion of skipping a generation. I’m very intrigued and interested in that. When Werner met my father, he immediately wanted to talk to him about his experience in Haiti being a farmer.

WC: And did your father want to talk to Herzog about it?

PH: My father was somewhat hard of hearing, and Werner asked him what shoes he wore when he distributed vegetables in Haiti. My father, who barely knew who Werner Herzog was, turned to me and said, “I like your friend.”

WC: In your printed interview with Herzog, he talks about his time in the Sudan, a very dark time for him, and he says, “I know the [hearts] of men.” Herzog is on a quest, I think, to approximate some absolute assessment of human morality. You and I are interviewing on a much more lighthearted note. What are you taking away from this whole project?

PH: There’s also a deep difference because Werner Herzog hates psychoanalysis. He says the only reason he knows the color of his eyes is because he shaves. I don’t feel that way; I think analysis is very interesting. Going into the basement or the attic to look at the old furniture is very intriguing.

As I think of it, I’m after the perfect conversation. I’m after the Platonic idea of what the best possible conversation could be, and therefore it eludes me like a collector who would hope in some way never to have the last piece in his collection. If he did, then it would be the death of the collector.

Will Corwin is a New York-based sculptor, writer, and curator. His interviews have been anthologized in The Little Magazine in Contemporary America (University of Chicago Press, 2015), About Trees (Broken Dimanche Press, 2015), and Tell Me Something Good (David Zwirner Books, 2017).