Lois Mailou Jones

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS September/October 1991, Vol. 15, issue 5.

Lois Mailou Jones was interviewed for Art Papers in conjunction with her exhibition at Hammonds House in the autumn of 1990. Mildred Thompson studied watercolor and drawing with Ms. Jones from 1953 to 1957 at Howard University in Washington. D.C.

Mildred Thompson: When did you first go to Europe?

Lois Mailou Jones: In 1937, during my first sabbatical leave from Howard University. I went there to teach in 1930, when I was twenty-five, and taught at Howard for forty-seven years. You will remember that I was a dedicated teacher. I not only had to get over what I was teaching to those students as strongly as possible, but I had to be a professional artist, to produce and to exhibit. Of course, the first exhibit, since the white galleries wouldn’t take us—Hale Woodruff or Wells or any of us—was one of the Harmon exhibits. I remember my first painting, The Ascent of Ethiopia, which was inspired by Meta Warren Fuller’s sculpture Ethiopia Awakening and Aaron Douglas. And when I came back from France, Alain Locke said, “Congratulations, I love what you did, I love your street scenes, and your studies of the Luxembourg Garden, in fact I’m using Rue Norvins in my book The Negro in Art, but you’ve got to do something with your heritage, the black subject.” Locke, with DuBois and Marcus Garvey, really instilled in us the philosophy of the “Black Is Beautiful” period. It hit me really hard, that maybe this was something I should do. However, being trained at the Boston Museum School, studying Sargent and Winslow Homer and all, was very important, very strong, and very inspiring. At the same time I felt I did owe something to myself and to my people, to the extent that I did Jenny, which was an oil painting of a black girl cleaning a fish, a very strong painting. It was an impressionist painting, which is what I did in Paris, when I was studying at the Académie Julian.

Thompson: When did the African period start?

Jones: It began in the ’20s when I was doing costume designing for Grace Ripley, the costume designer for the Denishawn dancers in New York, and the branch school. Many times they wore masks, and I loved to make them. And in doing research for them I came upon African masks. Even at Columbia University, in 1934, I did my graduate research on the history of the mask. The strongest things that hit me were the masks from Africa.

Thompson: But you went through a marvelous period of impressionism in Paris, as strong as anyone’s work I’ve ever seen. And the things of yours I’ve seen since then don’t have that quality. Why could you not have continued a style that you seemed born to?

Jones: The Black Art period came in. And you can say, well, it was a wonderful thing for the black artists to get together and to decide that we’re going to have black art shows—but to me, it sort of blocked my career.

Thompson: But you were going in your own direction, as in that impressionist painting of the girl with the fish…there was no need to leave that. The things since then are interesting, and they’re strong, but aren’t they a whole different thing?

Jones: I think going to Haiti did a lot to change me. And you know, I believe that every black artist should participate in the movement—but I don’t limit myself to the black subject. I may see a beautiful landscape I want to interpret, and since I paint from feeling, I’m liable to do something that has nothing to do with black art. I’m absolutely free as to what I express; I cannot be dictated to. As I said to the students yesterday, “Remember, I am not an African. I have to do research, I have to study.” But when I did that painting in Paris, way back there in ’37, and I took it down to the Académie Julian, they were amazed; they said, “But this doesn’t look like a Lois Jones painting.” They were used to my street scenes up in Montmartre, impressionism and such, and to do a thing like that, they couldn’t understand, and I said, “But remember Picasso and Braque and Matisse and Modigliani and Brancusi—look what they did, going to African art. It’s my heritage—I mean, I can make it mine, because I’m more a part of it than they were.” In Paris, everything was African art—in the art galleries, all along the streets in Montmartre, Montparnasse, they were promoting the beauty of African art. I went back to the mask sketches I had done for Grace Ripley and something really happened to me, I just felt I had to do that painting. By the way, the National Museum of American Art just bought it for $37,500 for the permanent collection, and they’re presenting it the way they did Catlett’s sculpture last year, along with about eight paintings which cover the changes that I’ve been through in my career. I’ve changed three times because of environment. The Haiti work, the Africa work, and the first, of course, was the impressionism and the watercolor at Martha’s Vineyard. And to think, I’m just now being recognized by the National Museum of American Art.

Thompson: But really and truly, how do you think your life would have been different if you had received this attention, say, thirty years ago? Fifty years ago?

Jones: As a black woman, I wouldn’t have received it.

Thompson: But if you had.

Jones: It was so hard, anyway, for women to gain recognition, and here I come along, a black woman doing impressionism—I was hurt to think that those paintings weren’t accepted, but it helped to build me up and put me where I belong—I mean, I’m very late with these things happening.

Thompson: Yes, but women like Louise Nevelson and Georgia O’Keeffe didn’t sell work until very late. And there are many male painters who didn’t. I’m fifty-four, and my financial circumstances are extremely limited, but by hook or crook somehow, I always have things to work with, I have money to buy paint. I probably could exhibit much more, but I always say why, what am I exhibiting for? Because usually I just hang things up, and then I go get them, and I bring them on back home. Really and truly, I don’t need to take them in the first place. You have your works hanging in your house, that’s your collection, and that’s the way I feel about my work. And I love it; if I didn’t I would destroy it. How do you feel about selling your work?

Jones: Money isn’t the thing that you really think of. I don’t like it when a student comes to me and asks, “Where can I exhibit my work?” Let’s get through with the study and the preparation before you think of exhibiting. I love to work, and when I’m doing a painting I’m not thinking of what I’m going to sell it for; I can live with it. In fact, I think I’ve held on to too many of my paintings. When Toby Benjamin and I went to see “Against the Odds” [a traveling exhibition of works from the Harmon Foundation shows], we checked the paintings as we went through the exhibit, and the labels said “Schomberg Collection,” or this or that collection, and when you get to Lois Mailou Jones, it was “Lois Mailou Jones Collection.” I’m still holding things that were done way back in the ’30s, never thought of selling them. Now, at eighty-five, though, I’m very concerned about what’s going to happen to the paintings, to the extent of talking with Barry Gaither, who’s said, “Lois, we’ve got to get them into museums. When you’re gone, that’s where they should be, whether you sell them or give them, let’s get them where they’ll be taken care of.” We made a list of all the museums where I would like for them to go, but it’s all coming very late. The museums aren’t necessarily coming out to buy black artists, and it’s just now that I’m really getting out there where I should have been thirty years ago. Thinking now not of selling, but of getting into the mainstream and gaining recognition—that’s the thing I’ve been fighting for, to pave the way for, especially, the black artists who follow after me. You know Catlett was one of my first students, and the things that she’s doing today, she did in design class when I introduced the idea of incorporating black heritage and black people into the works. I introduced that, along with the things that were probably inspired by important white artists, like John Singer Sargent and so many of the others. Anyway, the first thing was to pave the way, to get out there. We were being ignored, and we have to get into the mainstream.

Thompson: Yes, but recently I saw the small biographies in the catalogue of the Wes Cochran collection of African-American art. And of these sixty-five or so black artists, probably sixty-three studied at places like Columbia or the Art Students League. We have been exposed to the best education that this country has to offer. We have also received all of the major grants; there are many who have received Guggenheims, many who have received the Fulbright, not three out of sixty-five, but twenty, thirty-five, forty. You talk about not being mainstream, we are as mainstream as you can be mainstream in this capitalistic society.

Jones: But we’re still not there.

Thompson: We’re not there, but nobody is there.

Jones: I was on a panel discussion in New York, with about six women including Isabel Bishop and Alice Neel. I said that I had studied at the Boston Museum School, I had scholarships…and Isabel Bishop had tears in her eyes, and she said, “But where have you been? We’ve never heard of you.” And I said, first I’d been teaching at Howard University, I don’t get up to New York too often, and I just didn’t have the contacts with those women. They came to the house, they almost fainted, looking at the impressionist things. They said, “But you’re a great American artist.”

It seemed like doing the things that were inspired by Haiti, in terms of Haiti’s relation to Africa, inspired by Voodoo—because as a designer, I was particularly interested in the design of the vèvè—that began to change me, the vèvè, and I did a whole series of paintings, using Haitian beads from jewelry in some of them. I did a whole series of works depicting the life of those people. The color changed in those works—it was no longer the silvery greys and the mysticism of Paris. It was Haiti, the black people, the wonder of them, the marketplaces, the way they paint their houses in these colors, and my whole palette changed.

Thompson: A while ago we were talking about audience. Who would you like your audience to be?

Jones: I want to be accepted worldwide, and not only by black people. I don’t paint just for black people, I’m painting for people to enjoy works that I have done as an American artist who happens to be black.

Thompson: Do you feel that you would not have accepted the black movement—the movement that says you have to be black, you have to paint black subjects—if you had not had the peer pressure? Do you feel that if it has to be black art, it has to be for a black audience?

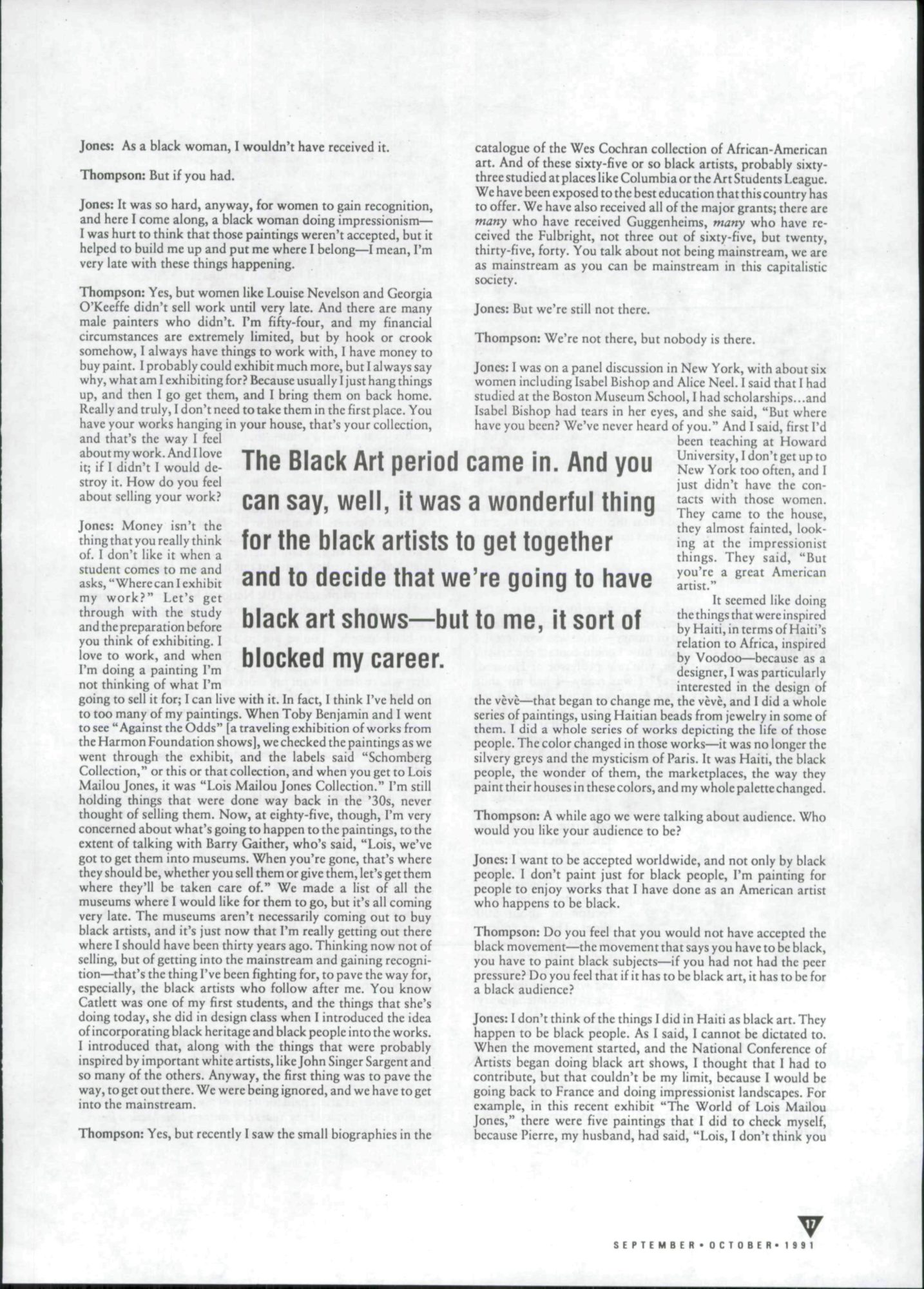

Jones: I don’t think of the things I did in Haiti as black art. They happen to be black people. As I said, I cannot be dictated to. When the movement started, and the National Conference of Artists began doing black art shows, I thought that I had to contribute, but that couldn’t be my limit, because I would be going back to France and doing impressionist landscapes. For example, in this recent exhibit “The World of Lois Mailou Jones,” there were five paintings that I did to check myself, because Pierre, my husband, had said, “Lois, I don’t think you can ever go hack to impressionism.” And I went back to France a year ago to prove that I could do it. Something happened to my palette, working with so much color in Africa and Haiti. People commented, “Looking at those first landscapes that you did in Paris, and then looking at these that you just did in France, your palette is stronger. It looks like you have arrived at something very strong.” And in these recent paintings, I’m sort of enjoying painting—I have to enjoy what I do. And the masks were so important—I think they’re still important. And the things that I have done. Moon Mask and Damballah, go back to Haiti, because Haiti has never broken her ties with Africa. When I’m there, and I hear the drumming and I see the people dancing, something comes back to me, and I feel that in my work.

Thompson: Have you lived in Africa for any length of time?

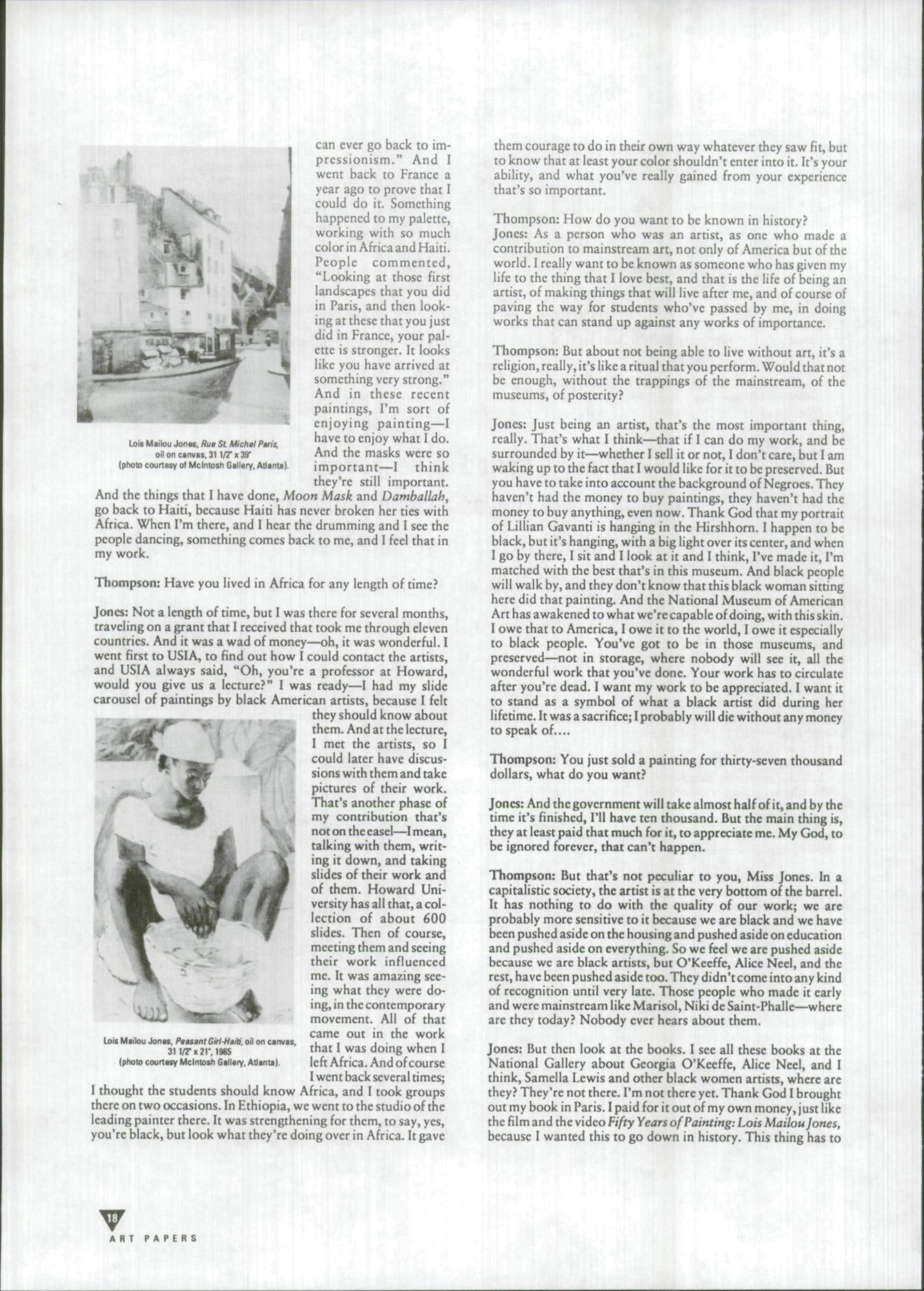

Jones: Not a length of time, but I was there for several months, traveling on a grant that I received that took me through eleven countries. And it was a wad of money—oh, it was wonderful. I went first to USIA, to find out how I could contact the artists, and USIA always said, “Oh, you’re a professor at Howard, would you give us a lecture?” I was ready—I had my slide carousel of paintings by black American artists, because I felt they should know about them. And at the lecture, I met the artists, so I could later have discussions with them and take pictures of their work. That’s another phase of my contribution that’s not on the easel—I mean, talking with them, writing it down, and taking slides of their work and of them. Howard University has all that, a collection of about 600 slides. Then of course, meeting them and seeing their work influenced me. It was amazing seeing what they were doing, in the contemporary movement. All of that came out in the work that I was doing when I left Africa. And of course I went back several times; I thought the students should know Africa, and I took groups there on two occasions. In Ethiopia, we went to the studio of the leading painter there. It was strengthening for them, to say, yes, you’re black, but look what they’re doing over in Africa. It gave them courage to do in their own way whatever they saw fit, but to know that at least your color shouldn’t enter into it. It’s your ability, and what you’ve really gained from your experience that’s so important.

Thompson: How do you want to be known in history?

Jones: As a person who was an artist, as one who made a contribution to mainstream art, not only of America but of the world. I really want to be known as someone who has given my life to the thing that I love best, and that is the life of being an artist, of making things that will live after me, and of course of paving the way for students who’ve passed by me, in doing works that can stand up against any works of importance.

Thompson: But about not being able to live without art, it’s a religion, really, it’s like a ritual that you perform. Would that not be enough, without the trappings of the mainstream, of the museums, of posterity?

Jones: Just being an artist, that’s the most important thing, really. That’s what I think—that if I can do my work, and be surrounded by it—whether I sell it or not, I don’t care, but I am waking up to the fact that I would like for it to be preserved. But you have to take into account the background of Negroes. They haven’t had the money to buy paintings, they haven’t had the money to buy anything, even now. Thank God that my portrait of Lillian Gavanti is hanging in the Hirshhorn. I happen to be black, but it’s hanging, with a big light over its center, and when I go by there, I sit and I look at it and I think, I’ve made it, I’m matched with the best that’s in this museum. And black people will walk by, and they don’t know that this black woman sitting here did that painting. And the National Museum of American Art has awakened to what we’re capable of doing, with this skin. I owe that to America, I owe it to the world, I owe it especially to black people. You’ve got to be in those museums, and preserved—not in storage, where nobody will see it, all the wonderful work that you’ve done. Your work has to circulate after you’re dead. I want my work to be appreciated. I want it to stand as a symbol of what a black artist did during her lifetime. It was a sacrifice; I probably will die without any money to speak of….

Thompson: You just sold a painting for thirty-seven thousand dollars, what do you want?

Jones: And the government will take almost half of it, and by the time it’s finished, I’ll have ten thousand. But the main thing is, they at least paid that much for it, to appreciate me. My God, to be ignored forever, that can’t happen.

Thompson: But that’s not peculiar to you. Miss Jones. In a capitalistic society, the artist is at the very bottom of the barrel. It has nothing to do with the quality of our work; we are probably more sensitive to it because we are black and we have been pushed aside on the housing and pushed aside on education and pushed aside on everything. So we feel we are pushed aside because we are black artists, but O’Keeffe, Alice Neel, and the rest, have been pushed aside too. They didn’t come into any kind of recognition until very late. Those people who made it early and were mainstream like Marisol, Niki de Saint-Phalle—where are they today? Nobody ever hears about them.

Jones: But then look at the books. I see all these books at the National Gallery about Georgia O’Keeffe, Alice Neel, and I think, Samella Lewis and other black women artists, where are they? They’re not there. I’m not there yet. Thank God I brought out my book in Paris. I paid for it out of my own money, just like the film and the video Fifty Years of Painting: Lois Mailou Jones, because I wanted this to go down in history. This thing has to live, as a statement about a black woman artist. I’m very proud of my people. You may say that black people didn’t buy my work, but I still have to think over and above that, that my work must contribute to raising the cultural standards and the place of black people.

Thompson: But at the same time that you’re saying that we must raise the cultural standards of black people, you must realize that the whole cultural scene in the United States is a wasteland. If that were the case, it really should be to bring

the cultural standard of the country up, and the blacks just reflect what everything else in the country is. I have taught in all-black institutions and I have taught in all-white institutions, and the caliber of the students, as far as intellect is concerned, is about the same, and their cultural orientation is the same. And it has to do more with caste and class. None of them know anything about culture. None of them has been taught to love the culture, or to listen to classical music, or to appreciate anything that’s not of the persona.

Jones: But there’s a lot that we have to do as black people. Those of us who are in a position to really raise the standards. You really should do something that at least speaks of black people. I’m very happy that the National Museum of American Art will hang that painting up for the American public, for anybody who comes there to look at it, “and you know she’s a black woman,”—because we need that status to encourage us of what we’re capable of, having been downtrodden for so many years, and belittled, and underrated. There’s been so much holdback that anything I can do to prove what a black woman can do, I do that.

Thompson: How do you respond to the new generation of artists? Do you feel that the kind of dedication and commitment one used to see thirty years ago still occurs today?

Jones: I don’t see any great art in the younger artists.

Thompson: Is this because of a lack of skill or technique?

Jones: No, it’s in their mind, what they’re thinking and what’s happening in the world—all of this is affecting them. I mean, they’re confused by what they’re seeing at the museums—even the museums are confused.

Thompson: Do you feel it’s because of the teaching? I find that most of the work lacks skill with bringing the material together, the paint on canvas, the pencil on paper. There’s so little behind that, and because the skill isn’t mastered, it’s impossible to express, to have something to express. I had four years of life drawing.

Jones: They don’t do that anymore. They just dash away at something, and say, when can I have a show?

Thompson: It’s a kind of capitalist attitude that makes that child who has had two lessons in art want to know, when can I have my exhibition. I tell them, if you came here and had two piano lessons, you would not ask me, when can I have my concert at Carnegie Hall, so why do you think you can come here and have a show after two art lessons?

Jones: But that’s it, it’s just this greed that’s overpowering minds to want to get what they want out of life as quickly as possible. All of that is entering into everything, into the art museums—let’s hope that those of us who are balanced can keep the situation stabilized. I mean, you’ve got to advance, to do things that really express our abilities and all of that, but there’s really a limit as to how far we can go with all of this happening in the world.

In my career, I have had many ugly experiences, but I have never grown bitter, because it would have hurt my work. And that’s fortunate. And I think living abroad was such a wonderful experience, in France where I was treated so well.

Thompson: Had you not had that experience of living in France, would you have been the artist you are today?

Jones: No. I often wonder if that was not your case, that living abroad…

Thompson: My experience in Hamburg sealed my fate. I had wanted to be a painter more than anything else in the world. It really began at Howard with Mr. Porter, who gave me my first courage, my first little bit of confidence, and then again at Skowhegan, with Isabel Bishop, and not anything at all at the Brooklyn Museum School—I had no problems there, but I didn’t feel I was being supported at the Brooklyn Museum School. I was the only black who had that grant, I was the only black in my class; when I applied for a Fulbright my teacher was on the committee and announced to the class that he could nominate only one student and he had nominated Fred because Fred would probably go on and paint but that Mildred who was equally as good would probably not be painting more than two or three years. Then I went to Germany, and I was treated like royalty—open the store, give her all the supplies, anything she needs. Then I had my first single show in Germany, and when I came back to the United States, I was so strong that nothing could affect me.

Jones: Well, that’s what I owe to France. I’m planning now to give France two of my works. I hope you’ll do the same with Germany.

Thompson: The Germans have already bought the work, it’s already in their permanent collections.

Jones: After a career of sixty years, my work will live. It’s at least established to that extent. I have that satisfaction. Enough has been done and said so that it will live. But at the same time, I think it’s timely that I do something in making it happen while I’m alive, because I think I owe it to my country and my people. I feel that I owe it to them to see that some of these things happen.