The Otolith Group, Sovereign Sisters, installation view, 2014, computer animation transferred to black and white, no sound, wood, glass reinforced plastic and purified water, 3 minutes 47 seconds [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

Living Worth Repeating—

On the Xenogenesis of the Otolith Group

Share:

Set across four galleries and three courtyards of the Sharjah Art Foundation’s Al Mureijah Art Spaces, the Sharjah chapter of Xenogenesis, conceived as a cross-section of works created between 2011 and 2018 by the Otolith Group, could not have better complemented the collective’s ethos. The exhibition was co-curated by SAF Director Hoor Al Qasimi with Annie Fletcher, who curated the show’s first iteration in May 2019 at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, which traveled to Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University and Alberta Art Gallery in North America and Buxton Contemporary in Australia, before arriving in Sharjah in November 2021, ahead of its opening at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, where Fletcher is now director, in July 2022. Accompanying the exhibition is an extensive catalogue, The Otolith Group: Xenogenesis, from which come many of this essay’s quotations.

Founded in 2002 by artists Kodwo Eshun and Anjalika Sagar, with an expansive practice that explores the material scales of deep, immediate, and multidimensional space-time, the Otolith Group integrates essayistic audiovisual compositions with writing, performance, curating, and discursive programming. They do this work to illuminate, magnify, and complicate the affective textures and enmeshments of lived histories to open avenues of relation through them: a movement that was echoed in the very architecture of SAF’s Al Mureijah complex.

Located within Sharjah’s historical quarter, with its traditional stone-courtyard houses and creek-lining souks, the Al Mureijah Art Spaces were completed in 2013, with an emphasis on integration and adaptive reuse. Designers Mona El Mousfy, founder of SpaceContinuum Design Studio, and cultural worker Sharmeen Azam Inayat transformed five buildings into white cubes and converted others to outdoor enclosures. Each renovation weaved into its surroundings, framed by the communities and landmarks encircling the complex, from residential blocks near Al Zahra mosque, serving Sharjah’s Shia communities, to the 18th-century pearl merchant’s home housing the Heritage Museum. Labyrinthine corridors between buildings lead to, and at points create, internal courtyards, naturally fragmenting any exhibition across the complex. That dispersal speaks to Otolith’s interest, as Sagar was quoted in a 2010 Frieze article, in “opening up the question of the postcolonial to a series of complex interlinkages that are implied, but which need to be unfolded project by project, so that what emerges is a complex and baroque aesthetic of constellations.”

The Otolith Group in conversation, 2021 [photo: Sahanavas Jamaluddin; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

Questions of the postcolonial fit the context of the Sharjah Art Foundation, whose recent March Meeting—the foundation’s annual convening, this year titled The Afterlives of the Postcolonial—fed into the upcoming 15th Sharjah Biennial in 2023, which materializes the late Okwui Enwezor’s vision for the show. But postcolonial concerns extend beyond SAF’s programming. There is the foundation’s place within the administration and civil society of Sharjah, and more broadly within the context of the United Arab Emirates’ statecraft and its navigation of a post-war international order since gaining independence in 1971—the year the country joined the Arab League, and two years before attending its first Non-Aligned Movement summit. In 2013, SAF formalized its allegiance to histories of Afro-Asian solidarity and Third World liberation, when Yuko Hasegawa’s Sharjah Biennial 11 announced a re-alignment toward the Global South. This pivot took into account the local and global communities SAF serves, political tensions brewing regionally at the time, and exhausting criticisms from a predominantly Western art press that refused to engage difference.

The Otolith Group, Anathema, installation view, 2011, 16:9 HD video with colour and sound, 37 minutes [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

All of which may explain why Sharjah’s iteration of Xenogenesis seemed to depart from an alternative starting point versus the Van Abbemuseum’s opening sequence of Anathema (2011) and From Left to Night (2015). In Sharjah, the HD video Anathema was screened in a roofless stone shell after sunset, as if in analogue resistance to the digital conditions that Anathema unfolds. This speculative visualization of what a smart screen sees when it looks out onto the world is filtered by grainy static. Images flow through. There’s a city seen from above; two people kissing; an experiment conducted in the Manchester Centre for Nonlinear Dynamics in the year 2000, introduced as “the transition to turbulence in liquid crystal hydrodynamics.” At points, television news broadcasts come on. In one from 2011, reporter Serene Branson is seen, while reporting from the Grammys, losing control of her speaking faculties as a result of an extreme migraine—an organic malfunction in a molecular matrix.

Anathema exists in what theorist Mark Fisher called cyberspace-time: “bitty, fragmented.” Embedded into a narrative of glitchy, magical surrealism—or, as the artists put it, a science fiction of the present, to borrow from J.G. Ballard—the work draws on Isabelle Stengers and Phillipe Pignarre’s writing on capitalist sorcery, and imagines smart technology with its own sentience, capable of enchantment.

Recalling curator Shumon Basar’s declaration that humans have become extensions of their phones and not vice versa,1 the swipe is reframed here as an ominous sorcery—what Fisher called, in a virtual lecture titled “Crisis Complex,” “Touch Screen Capture”—enacted not by humans but, as curator Anselm Franke put it, by “the phantasmagoric animism of undead capital.”

There’s a Promethean curse embedded in the title, wherein the mythological gift of fire, as with the biblical crime of knowledge, finds its pharmakon equivalent in a smartphone’s mesmerizing blue screen. The term anathema, ancient Greek for “a thing devoted or dedicated to,” is broadly defined today as curse, but its etymological roots are neutral. Apparently, it’s used in the Old Testament to refer both to revered objects and things that cause destruction in God’s name. Considering the smart technologies that define so much of contemporary life originated as tools of conquest, surveillance, extraction, and control for the US military industrial complex, it all sounds pretty familiar.

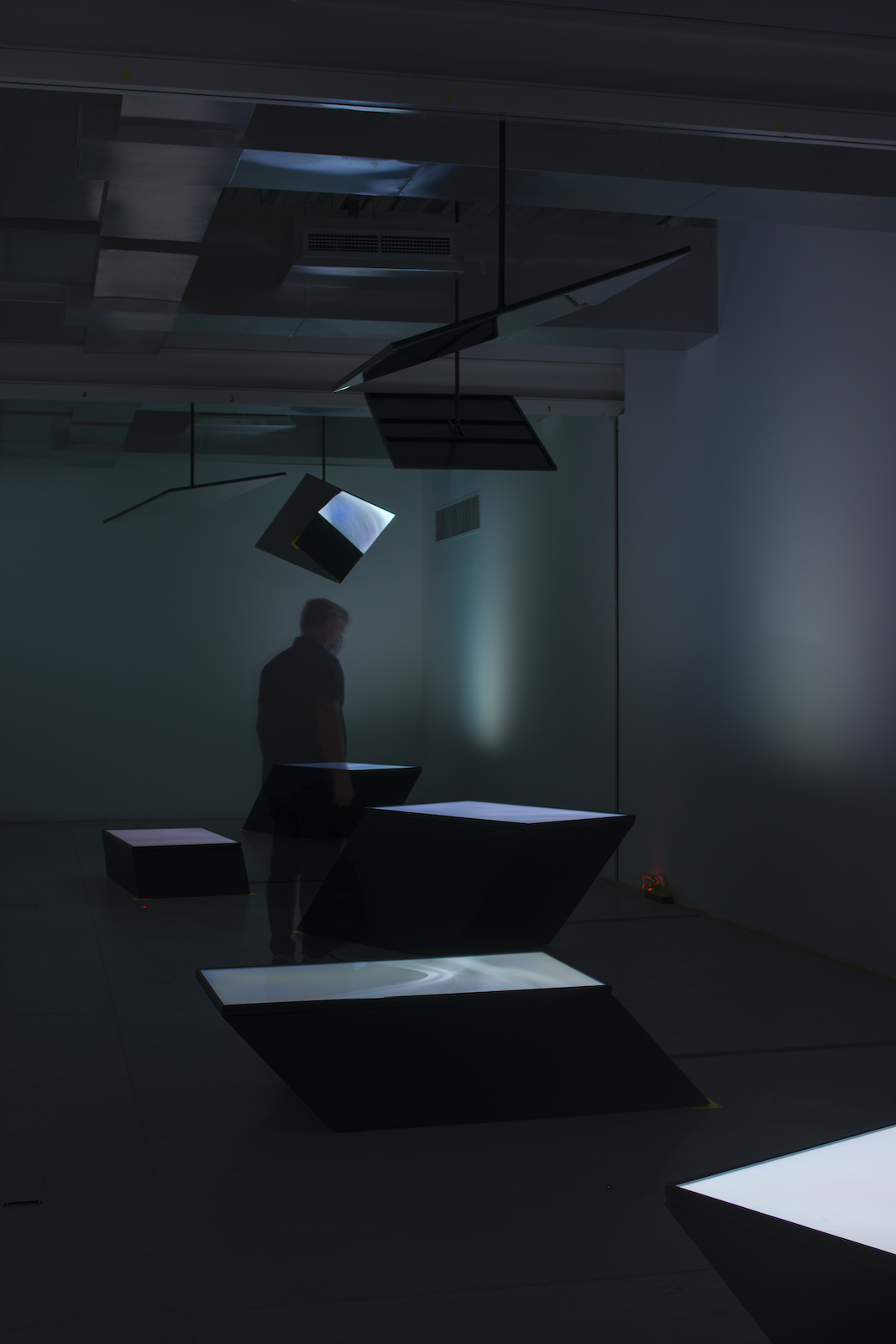

The Otolith Group, From Left to Night, installation detail, 2015, 5-channel 16:9 HD video installation with colour, no sound and mirrors, digital screens; variable duration [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

The Otolith Group, Anathema, installation view, 2011, 16:9 HD video with colour and sound, 37 minutes [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

The screen’s tactility is misleading, then. Although “images promise immersion, proximity and touch,” Franke writes, they do so “across a specular threshold that can actually never be crossed.” So, Anathema loosens the net. “We wanted to enter into the fantasy, and show how that fantasy operates, to show the dream that communicative capitalism has of itself,” the artists state. “Every screen becomes a portal, every portal becomes a threshold, every threshold becomes liquid,” and “If you zoom into the skin of all those smiling faces, what you get is this animated geometrical landscape.” That terrain is further abstracted in the five-channel installation From Left to Night. Black mirrors angled above five screens duplicate, warp, and extend the crystalline, digital abstractions forming below them—like the lights of a city seen from the sky after sundown.

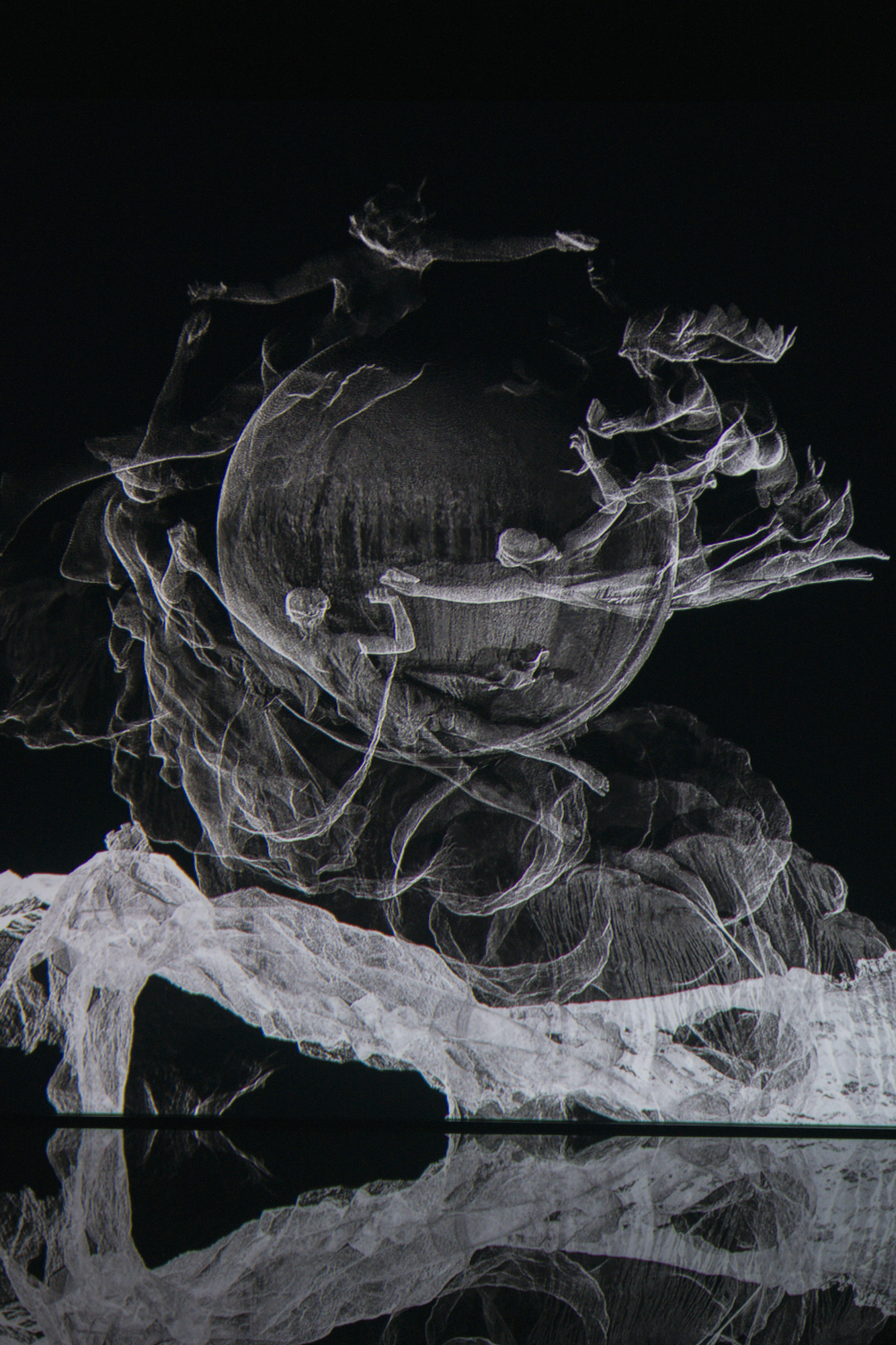

From Left to Night was shown in a room closed off from a cavernous Sharjah gallery, where the monumental Sovereign Sisters (2014) held court. The artists used 3-D LiDAR technology to scan and animate Autour du Monde, a monument inaugurated in 1909 by the Universal Postal Union in Bern, Switzerland, consisting of a giant globe flanked by five flying women, each representing a geographic region: Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe, and Oceania. On its website, Otolith describes the sculpture as an exaltation of the UPU’s imperial ambitions as a global communications network2—“a portrait,” Eshun put it in one interview, “of Europe’s imperial vision of a planet united under white rule.”3 Since its inception in 1874 as the General Postal Union, the UPU, as it was renamed in 1878, has standardized postal communication worldwide, and in 1948 the organization became a specialized agency of the United Nations, under which it “continues to plan the planet’s postal networks.”4

The Otolith Group monumentalizes this shifty continuity by producing a simulacrum that magnifies what’s at stake. Autour du Monde appears, as if in the round, on either side of a large, black screen that sits in a wide, flat pool of black water, amplifying its use of women’s bodies to symbolize territories—a classic imperialist trope that adorns the corners of some of the oldest world maps, and, in the case of Milan, the interior arches of Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, one of the world’s oldest shopping centers. “The language of female allegory suits the voices of those in command,” writes Marina Warner. A worded statement can be more easily refused, but the body’s image “draw[s] us to consent to its meaning” because it puts our “identity as human beings … at stake.”

Questions of consent and obfuscation speak to the UN’s own shady origins as a project led by Euro-American colonizers seeking to protect their interests. This history is exemplified in the story of a South African politician who participated in the design and implementation of apartheid, and who is credited with adding the phrase “fundamental human rights” to the UN Charter’s preamble. (In a 1947 letter addressed to the UN General Assembly, W.E.B. du Bois called the hypocrisy of this endeavor a “basic problem of humanity,” so long as nations commit such atrocities as Belgium’s enslavement and murder of the peoples of the Congo, and America’s continued denial of Black Americans’ rights.)5

The Otolith Group, Sovereign Sisters, installation view, 2014, computer animation transferred to black and white, no sound, wood, glass reinforced plastic and purified water, 3 minutes 47 seconds [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

More than an animation, then, Sovereign Sisters is a spectral data-point indictment that raises “the undead spirits of infrastructure and automatism that lie dormant and sublimated within Saint-Marceaux’s patriarchitecture ….” It does so to resist that sublimation of a still-unfolding project of global capitalist capture, which Otolith consistently disrupts: a Sisyphean deposition against the amnesia and paralysis brought about by forces that keep hoisting dead White men on dead horses.

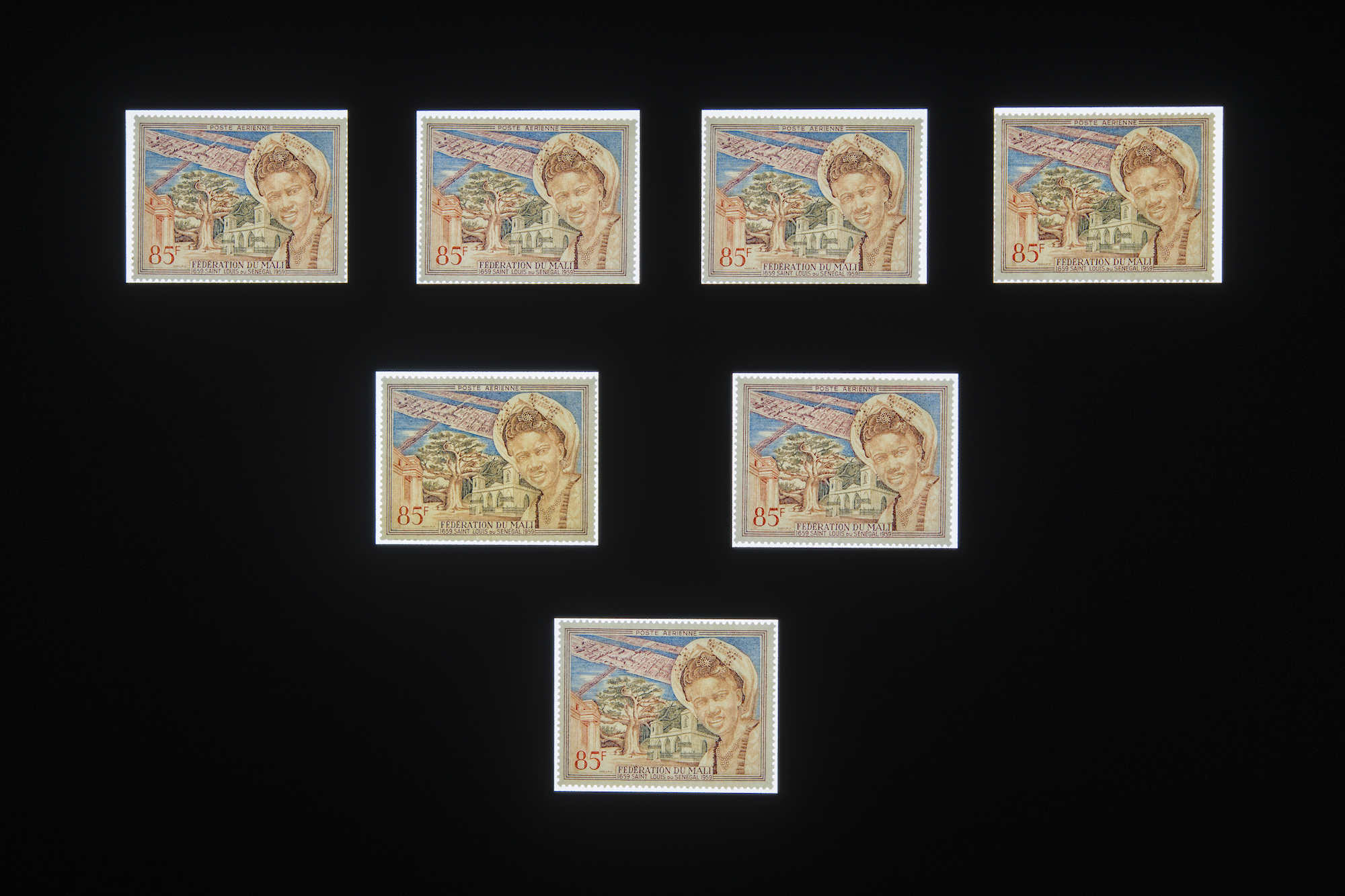

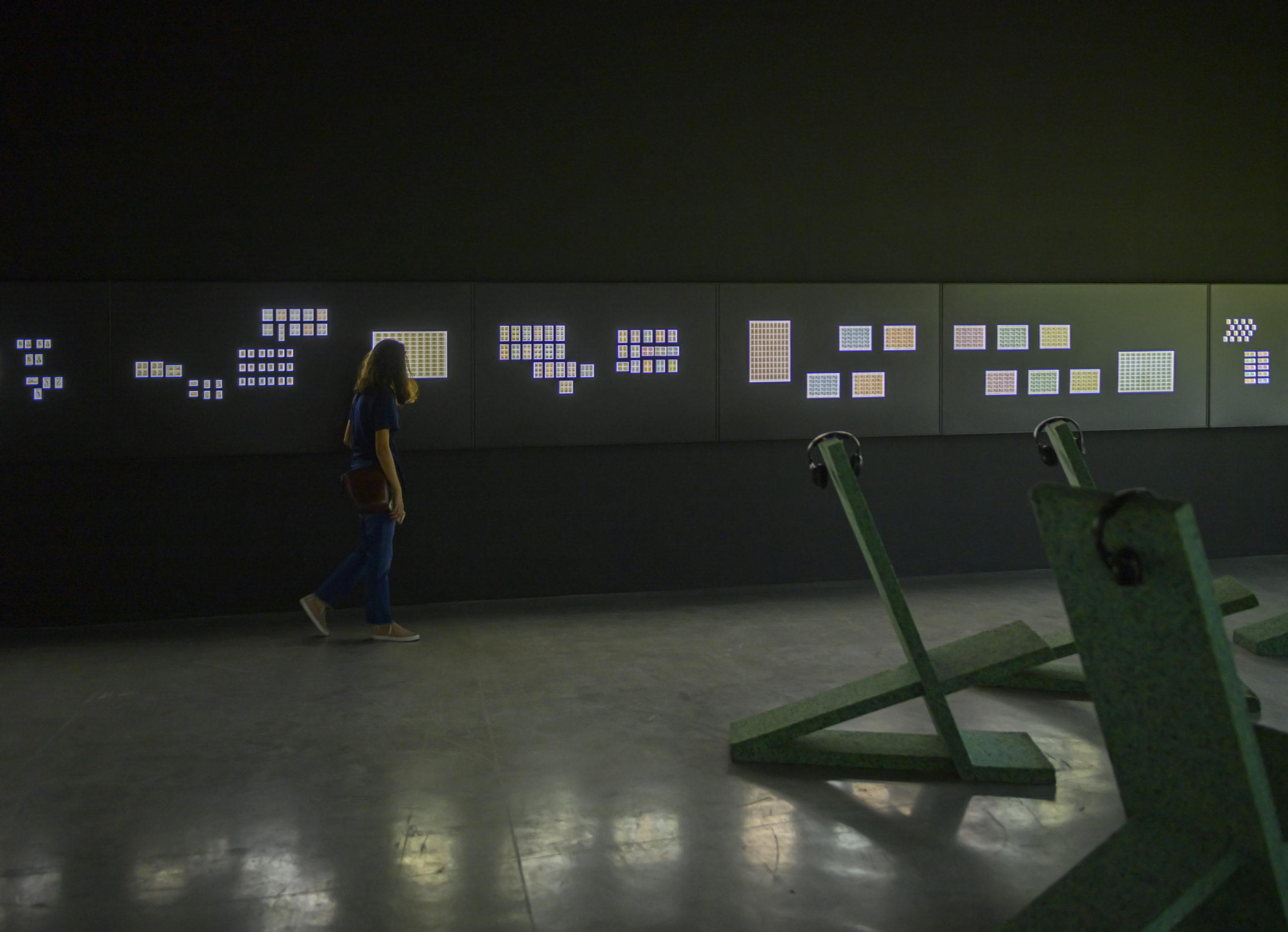

The Otolith Group, Statecraft: An Incomplete Timeline of Independence, installation view, 2014–2019, installation with postage stamps, lightboxes consisting of various materials, LED;1 x 60 meters [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

With that, it makes sense that Xenogenesis began in Sharjah with a different pairing, or so it seemed based on the small vitrine housing otoliths—acquired by the Environment Agency of Abu Dhabi—positioned, like an introduction, next to the exhibition wall text at the entrance to one gallery. (Otoliths have appeared in the collective’s others shows: at Van Abbemuseum, on loan from Rotterdam’s Natural History Museum; at Buxton Contemporary, from the School of BioSciences, the University of Melbourne.) Installed in a pitch-dark space are the two other works in the postal politics trilogy, which Sovereign Sisters concludes: the single-channel In the Year of the Quiet Sun (2013), and a taxonomy of stamps lining the walls that constitute Statecraft: An Incomplete Timeline of Independence (2014–2019).

In the Year of the Quiet Sun refers to the decrease in the solar surface’s temperature that occurs every eleven years, which became the subject of an international scientific inquiry between November 1964 and November 1965. The event was commemorated around the world with postage stamps whose designs featured hyper-optimistic projections that masked what was transpiring in real time. Zeroing in on Ghana, whose flag’s Black Star came to symbolize the dream of a united Africa, the video essay opens with an intertitle describing stamps issued by the new state between 1957, when Kwame Nkrumah became the republic’s first prime minister, and 1966, when he was deposed by military coup. (In a call-back to the UN’s Euromerican foundations, we later learn Ghana’s stamps were created in New York by the Ghana Philatelic Agency.)

The Otolith Group, Statecraft: An Incomplete Timeline ofIndependence, installation view, 2014–2019, installation with postage stamps, lightboxes consisting of various materials, LED;1 x 60 meters [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

The Otolith Group, Statecraft: An Incomplete Timeline of Independence, installation view, 2014–2019, installation with postage stamps, lightboxes consisting of various materials, LED;1 x 60 meters [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

Among the first stamps to appear onscreen are those bearing the name of the Universal Postal Union, each featuring the profile of George VI looking at yet more female personifications: the world-as-woman in one, the Autour du Monde making an appearance in another. Closeups of Queen Elizabeth II and Nkrumah follow, as does an image of the Ambassador Hotel in Accra. “It’s March 6, 1957, the day of independence,” Sagar tells us in a steady voice. Someone is reading an article about the stamps being issued with the head of the king replaced by that of Nkrumah, who is regarded as a father of Pan-Africanism. “Is this the first step towards dictatorship? Or the next stage in its decapitation?” asks Sagar—questions that find no neat answers in the decades that followed, as Africa’s decolonization gave way to debt, “development,” and geopolitical intrigue.

Taken from Joachim Hellwig’s 1964 documentary Black Star, archival footage in In the Year of the Quiet Sun shows scenes tracking Ghana’s Volta River Project, which, as with projects instigated by other industrializing nations at the time, sought the energy of hydroelectric dams. There are clips of a ship at port, presumably Tema, Ghana’s first planned city and key node in the Volta River scheme, which began operating around 1962, the year after Congo’s first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, was assassinated amid a crisis of sovereignty.

Eshun describes Lumumba’s murder as one of the 20th century’s most consequential. (The Belgian government finally took responsibility in 2002, whereas the CIA has been less forthcoming.) It occurred amid a series of shattering events that derailed the decolonial momentum propelled by the entry of Africa’s newly independent states into the UN General Assembly.6

This moment was, as South African writer Ruth First observed in 1970, when the Pan-African liberation project went into reverse.7 “We watch Ghanaian and Nigerian military watch Congolese soldiers coerce politicians,” Sagar says in the video. Her words infuse the frame as a slideshow of stamps acknowledges the first anniversary of Lumumba’s death. The stamps come from around the world, not just the continent, including Mongolia and the United Arab Republic, the latter an expression of a Pan-Arab movement that was equally ambitious, and which met with an equally nebulous fate. At that time, the colonized peoples of the world shared an intense solidarity, after all. As Sagar says in her narration, with images from Indonesia—independent since 1945—coming into view: “Each liberated territory [was], for a certain time, promoted to the rank of guiding territory.”

Ghana was one of those territories, with Nkrumah’s writing foreshadowing the neoliberal counter-revolution to come, whereby colonialism, as a process predicated upon territorial acquisition, would give way to imperialism as an economic form of subjugation. The Non-Aligned Movement sought to dismantle this dynamic when, in 1974, its call for a New International Economic Order—taking into account the entrenched asymmetries created through chronic colonialism—was adopted by the UN General Assembly. One year earlier, NAM held a meeting in Algiers within days of General Augusto Pinochet’s military coup in Chile against Latin America’s first democratically elected socialist president. Although some call Pinochet’s crime the birth of neoliberalism, it was in Ghana, in 1966, says Eshun, where the ideology found its footing on the continent. There, too, a coup d’etat opened the door for the International Monetary Fund and World Bank—institutions established at Bretton Woods in the United States—to lock the country into their debt-based principles.

Holding all this history in view, In the Year of the Quiet Sun steadies its gaze on a time saturated with immeasurable affect and appalling indifference, fetishized triumphs and nostalgic failures, actual wins and devastating losses. It possesses a heady, poethical intensity—a turbulence of densities and overlapping histories of empire, decolonization, and Cold War binarism—that resists the “futurist triumphalism” characterizing the “rhetorical gambles,” which leaders including Nkrumah took—gambles, Eshun says, that “could not actually guarantee their own outcomes.”

The Otolith Group, Statecraft: An Incomplete Timeline ofIndependence, installation view, 2014–2019, installation with postage stamps, lightboxes consisting of various materials, LED;1 x 60 meters [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

Statecraft takes a similar position. The 60-meter sequence of stamp collections celebrating the independence of African countries wraps around In the Year of the Quiet Sun like a frame, lining the walls of the gallery from start to finish. Each mini-document is a monument to, and remnant of, “a project of national internationalism, of Pan-African socialism, which was interrupted, terminated and destroyed,” says Eshun: “small items that spoke to an epic political project: to change the continent and thereby change the world.”8 It begins with stamps, captioned by an engraver in Philadelphia, that mark the centenary (without explicitly stating so) of the year 1847, when freemen of the American Colonization Society declared the Republic of Liberia, with a medley of national symbolism, including a five-pointed Lone Star; the goddess Liberty; and a monument to Joseph Jenkins Roberts, the colony’s first Black governor and the first president of Liberia. The timeline concludes with stamps dated 2012, each depicting an animal—a Nile lechwe, shoe-billed storks, and bearded vultures—to mark the first anniversary of the Republic of South Sudan’s independence.

As with Anathema, Statecraft is an exercise in speculative looking; one that, writes Eshun, “neither elucidates nor celebrates the ways in which the newly independent governments celebrated the ceremony of independence.” Rather, it “visualises Pan-Africanism in the same ways as the states themselves,” and “sees like a state by restricting itself to the ‘internal construction of image’ produced by the state.9” That focus is amplified by the alien presence of the stamps in the gallery, each backlit, their bright and, at times, melancholy acid tones reflected in the colorization of In The Year of the Quiet Sun. The result is what Sagar describes as a productive alienation. The kind engendered by the generative displacement of the stamp as a ubiquitous marker of global infrastructure, “whose monumentalism,” writes Eshun, is a form of “mass-manufactured miniaturism.”10

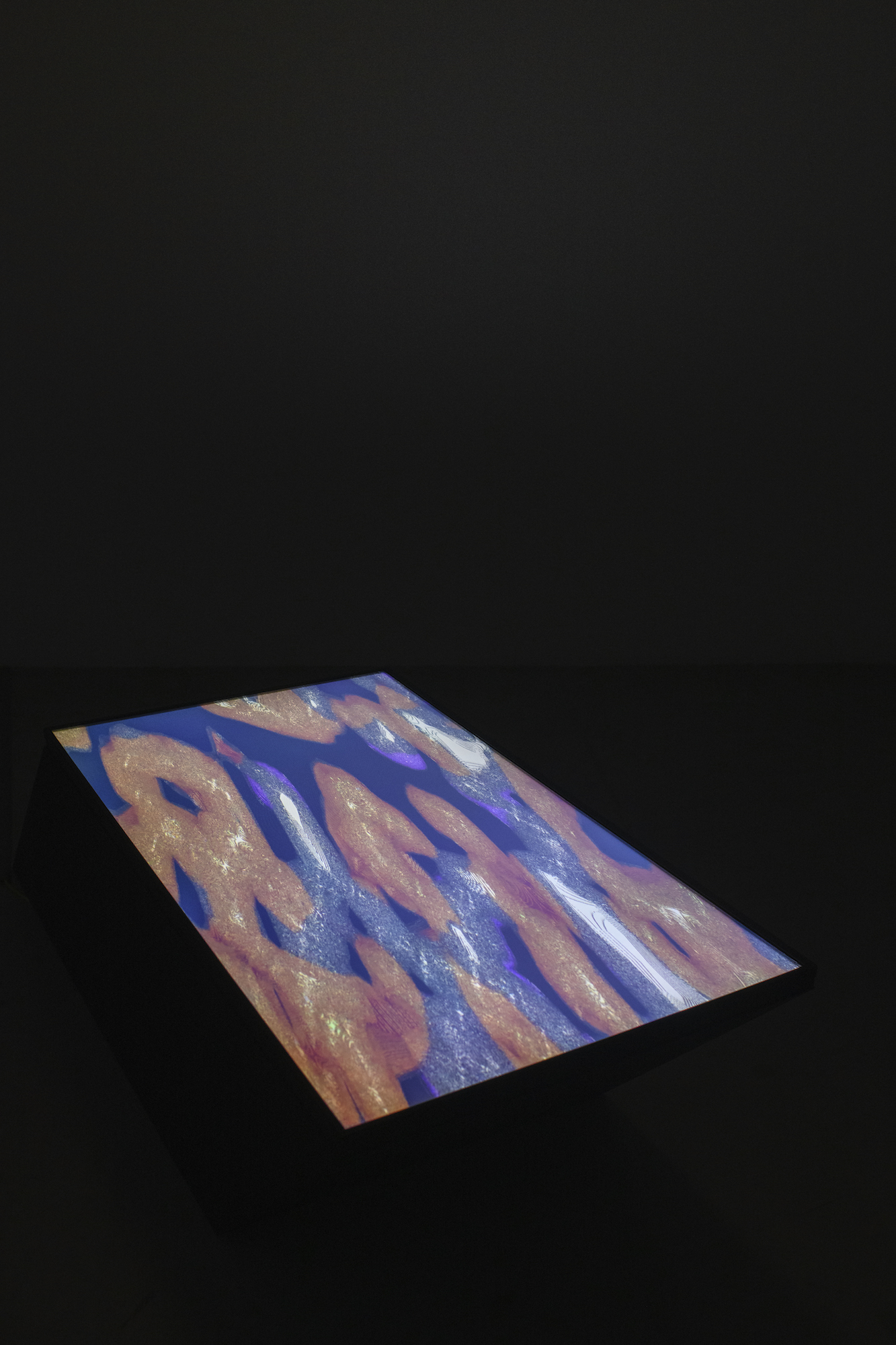

The Otolith Group, From Left to Night, installation detail, 2015, 5 channel 16:9 HD video installation with colour, no sound and mirrors, digital screens; variable duration [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

The Otolith Group, Statecraft: An Incomplete Timeline of Independence, installation view, 2014–2019, installation with postage stamps, lightboxes consisting of various materials, LED; 1 x 60 meters [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

Like an assemblage of temporalities, Statecraft creates the cognitive conditions to see in transtemporal dimensions. Here, the miniature is magnified to make “colossal forces” visible, distilled into their tiny frames with a scale that is “never less than planetary.”11 Each stamp propels itself back in time, to the moment when alternative political futures—ones that deviated from already-laid imperialist tracks—became foreclosed, and then propels itself back again to those futures, in order to trace their roots and offshoots in all directions. The intention is not to revisit the past and fight the same fight, or to complete a scientific breakdown of what worked and what didn’t, says Eshun, but to open up what Glissant described as “the prophetic vision of the past.”12 New questions and answers arise accordingly. “Every time we return to a moment in history, you register that you’re in a different problem space from that time,” Eshun points out.13 Today, for example, there are those who would prefer to declare decolonization a failure located in a fixed moment in time, rather than to acknowledge that it was a process which never had a chance to really take root.

To walk into the open air to be a welcome reprieve after an installation so all encompassing. While traversing corridors and turning corners, I found room to consider the lingering echoes of what had been seen, heard, and felt. Moving between the spaces tempered that dizzying experience Otolith often invokes, leaving viewers to search for the same horizon that Sagar once described when explaining the collective’s name. “Otolith are basically crystals in your inner ear that guide your sense of orientation and balance in the world,” she told an audience at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2019. She became aware of them when floating in “zero gravity” while filming the collective’s first video cycle, The Otolith Trilogy (2002–2009). Cosmonauts advised Sagar to avoid motion sickness by looking for the horizon line.14 The metaphor suited the collective’s aims, Sagar remembers—to seek out a horizon amid agravic fragmentation. To find balance within imbalance.

Horizons come in many shapes and forms. In one courtyard in Sharjah, they appeared as monumental portraits of science fiction maven Octavia Butler and queer Black American composer Julius Eastman, who are enduring influences on the collective’s work. Otolith borrowed the title of Butler’s 1980s trilogy for the exhibition, as well as a broader project focused upon Black feminist thought, DXG: Department of Xenogenesis. Merriam-Webster intriguingly defines xenogenesis as “the fancied production of an organism altogether and permanently unlike the parent.” It’s a fitting definition for a show such as this one and the political project it represents, encapsulated by In the Year of the Quiet Sun’s close-up shots of stamps depicting a white sun eclipsed by black: a visualization of a nascent Black universal that emerged when colonized peoples actively sought common ground. Or, to quote Sagar quoting da Silva: “difference without separability.”

Otolith Group’s members, born in 1966 and 1968, came of age in and around that moment and its aftermath. They grew up in a Britain defined as much by the abhorrent politics of Margaret Thatcher and Enoch Powell as it was by Stuart Hall, two-tone, and a conception of political Blackness that, out of necessity in a hostile environment, had Afro-Asian diasporic communities forming allegiances among themselves, in an echo of what was happening in the world at large. The deferral of these ruptures, these visions of some future otherwise, is something Otolith’s members resist in their insistence on working together and picking up where the Black British Arts Movement left off, as the YBAs (Young British Artists) became the art world’s counter-revolution equivalent, and a fetishized group of mostly young, White artists eclipsed the crucial decades when Black art in Britain, and political Blackness more broadly, not only constituted a challenge to centuries of erasure, but opened up horizons for the future.

Sagar and Eshun formed Otolith Group amid the aftermath of September 11, as a new racist axis formed. Since then, they have insisted on confronting histories that were stunted but not entirely erased, all while exploring what it means to embody difference without separability in a world that has yet to grapple with its intrinsic, organic, and always potentially combustive interconnectivity. For da Silva, to live with difference and connection is to abolish the modern text, with its “scientific imaging of The World as an ordered whole … composed of separate parts relating through the mediation of constant units of measurement and/or a limiting violent force”—all of which “feeds a racial grammar whose articulations of cultural difference with scientific signifiers has resulted in … an unbridgeable ethical divide.”15

The Otolith Group, Statecraft: An Incomplete Timeline of Independence, installation view, 2014–2019, installation with postage stamps, lightboxes consisting of various materials, LED; 1 x 60 meters [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

To build bridges in the context of seemingly irrevocable divisions, then, becomes a radical task—the kind that poses simple questions that require complicated, collective answers. Like how to live together on a suffering planet, and how to confront traumas of the past without re-enacting them.

Otolith splays these thoughts on the editing table to find new points of departure, and it follows those who showed the way. As is the case in The Third Part of the Third Measure (2017), a monumental performance of three compositions by Julius Eastman, whose “militant minimalism,” Otolith states, “initiated a black radical aesthetic that revolutionised the East Coast’s new music scene of the 1970s and 1980s.”16 The work’s title comes from a speech that Eastman gave ahead of a concert at Northwestern University in 1980, during which he explained both the logic of the composition—the third part of the measure has to contain all the information of the first two parts and “go on from there”—and his incorporation of racial and homophobic slurs into his composition titles, which drew consternation among faculty and students. (“Either I glorify them or they glorify me,” said Eastman, “and in the case of guerrilla, that glorifies gay.”)

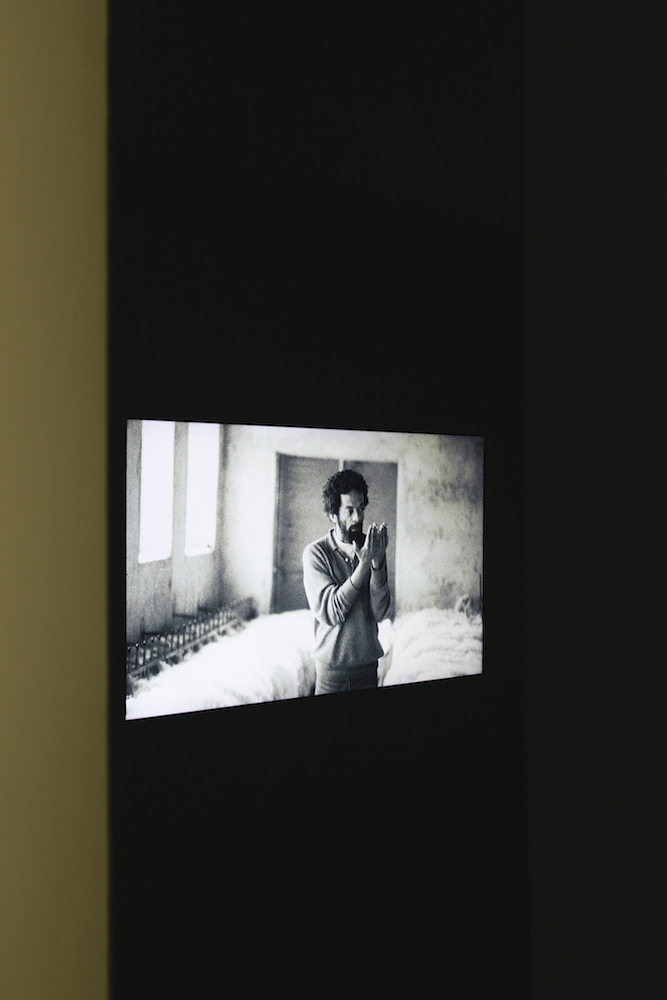

The Otolith Group, The Third Part of the Third Measure, installation view, 2017, 2-channel 16:9 HD video installation with colour and sound; 43 minutes [photo: Shanavas Jamaluddin; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation, and ICA Philadelphia]

For The Third Part of the Third Measure, Otolith Group restaged Eastman’s 1980 performance by using four pianists, two pianos, and three cameras, with male and female actors—Dante Micheaux and Elaine Mitchene—each performing Eastman’s speech at either end of the composition. The music is a wall of rising, pulsating, spiraling sound: a cyclical flow of overlapping notes, three descending down and a staccato two-tap up in tandem, where Eastman built up and peeled back layers of the composition. As is its method, Otolith took great care to ensure this work would be one of music, rather than one about music: “an experience of watching in the key of listening,” or a sonic image, whose intensity the artists attribute to how Eastman’s music became the method by which the work was made. The implications of this mode are limitless, especially when one considers how music, designed for interaction, participation, improvisation, and engagement, might offer the most effective diagram to illustrate what “difference without separability” could mean as praxis.

Otolith illuminates this potential in People to be Resembling (2012), a 21-minute montage that pays homage to post–free jazz music trio Codona, founded in 1978 by multi-instrumentalists Collin Walcott, Don Cherry, and Naná Vasconcelos, who produced three albums before Walcott’s untimely death. The work’s title quotes Gertrude Stein’s 1920s novel The Making of Americans, with an excerpt from the book appearing on the back of the band’s first album’s sleeve. In the film, we hear and see parts of Stein’s text—for example, “always repeating is all of living”—as black-and-white photos of Codona from 1978 depict the three days the bandmates spent in Ludwigsburg, Germany, recording their first album. Statements on living and being stretch into tautologically rhythmic lines whose syntactical recombinations conjure a charged, contradictory sense of monotonous yet unpredictable repetition and momentum rooted in keywords that punctuate the flow of images and sounds: of living, being, knowing, having, resembling, repeating.

The Otolith Group, People to be Resembling, installation view, 2012, 16:9 HD video with colour and sound digital scans and archival photographs, seating, rug, flat screen, 21 minutes 42 seconds [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

The Otolith Group, People to be Resembling, installation view, 2012, 16:9 HD video with colour and sound digital scans and archival photographs, seating, rug, flat screen, 21 minutes 42 seconds [photo: Danko Stjepanovic; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

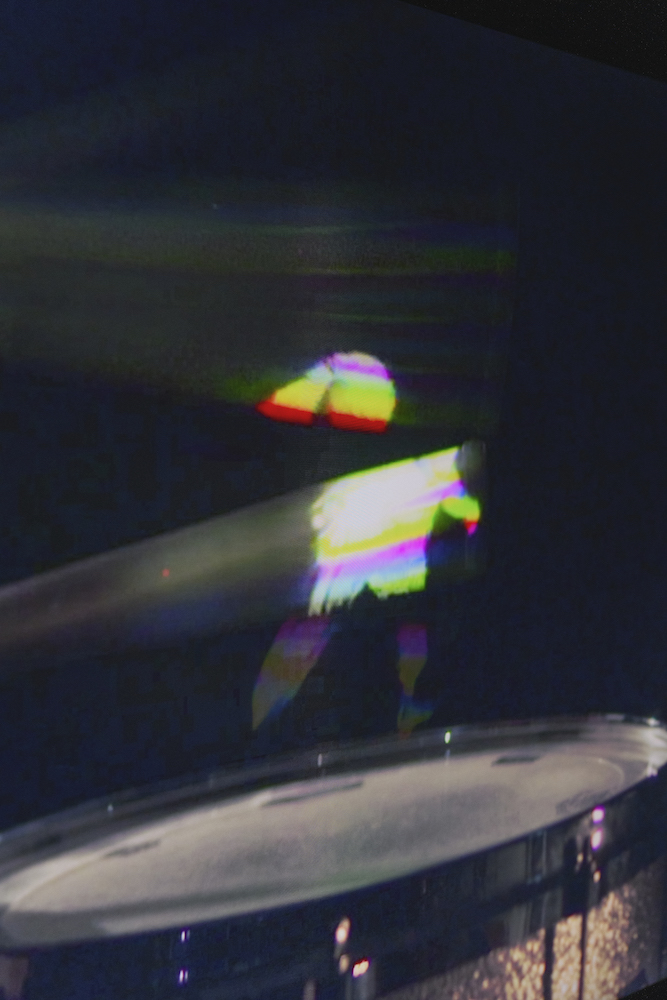

The photographs that appear throughout, mostly sourced from the archives of Roberto Masotti and Isio Saba, are among the few documents that show Codona playing as one. The images are threaded together with film of experimental drummer Charles Hayward—who uses gongs, cow bells, darbukas, and other instruments to create the percussion sounds that drive the work—as well as footage from the archive of ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax that depicts Asian and African folk dancers, each in a moment of heel-turning rotation. Codona music is finally heard in People to be Resembling at the end, when Otolith focuses the camera on Hayward playing with a pair drumsticks, their movements creating a “screen” on which a hologram-like image of students performing capoeira emerges. At points, the black-and-white projection transforms into a rainbow glitch.

Xenogenesis, then, is a conjuring: of people and places from within and from beyond the present frame of time and speech, and of testimonies scored forth from an earth that holds all our stories, whether it tells them or not. Such was the experience of Medium Earth (2013), a tectonic portrait of Southern California that moves from a subterranean car park to cuts of boulders, roads, the sky, and back again. In Sharjah, it was screened in a large courtyard at night, where ambient sounds punctured the space between screen and speaker to augment the sonic composition. That same spatial experience took place in another enclosure, where Medium Earth’s grounded frame expanded into O Horizon (2018), a moving portrait of Visva-Bharati University, established in 1921 in Santiniketan, West Bengal, by polymath and Pan-Asianist Rabindranath Tagore, whom Sagar describes as the beating heart of Indian modernism.

The Otolith Group, O Horizon, installation view, 2018, original format 4K video installation with colour and sound, projection screen, cork, rubber, seating, 81 minutes 10 seconds [photo: Shanavas Jamaluddin; courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation]

Tagore founded the school at Santiniketan to restore and reimagine cultures of care, craft, and connection between people and land that had been severed by British imperialism, says Sagar. But even though O Horizon acknowledges Tagore’s legacy at the outset, opening with lines from his poem “1400,” which addresses a poet “A hundred years from today,” what follows is not a hagiography or chronicle of Tagore’s life. Rather, it is an expansive capturing of what Tagore left behind: a living legacy of such quotidian monotony and grounded continuity that it becomes a profound and enduring monument to a vision and its survival, diluted through time but with potency all the same.

Slow and sweeping, the camera evokes the work’s title (the O horizon is the top layer of organic matter on the Earth’s surface), as it holds everything in equal perspective, scrolling slowly sideways as often as it tilts up to the sky, then back down to the soil, and back up again, creating an expansive frame that renders the school’s day-to-day activities epic—whether Hindi or Chinese lessons, or outdoor performances by dancers wearing opalescent noh masks, as they move, trance-like, to the sounds of cymbals, drums, and flute. “We were interested in cohering the site in its fragments,” Sagar explains. “To think about what it proposes as a thinking space.”

To create the conditions to think together in a broken world and take up what too often feels like a floundering struggle; to honor the groundwork already covered and commit to being together in difference; to flip the bird at those who are more concerned with dividing people by race rather than with uniting to abolish and confront the crime of race; feels like a good place to (re)start. A living worth repeating.

Stephanie Bailey is editor in chief of Ocula Magazine, a contributing editor at LEAP, and a regular contributor to Artforum International, Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, and dɪ’van: A Journal of Accounts. Formerly the senior editor of Ibraaz, where she worked 2012–2017, Bailey is also a member of the Naked Punch editorial committee; a managing editor of Podium, the online journal for M+ in Hong Kong; and the current curator of Art Basel Conversations in Hong Kong.

References

| ↑1 | Stated at 2022 Global Art Forum press conference at Art Dubai. Author present. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Sovereign Sisters,” on the Otolith Group website, http://otolithgroup.org/index.php?m=project&id=215, online. |

| ↑3 | Xenogenesis as a Diagram for Thought: The Otolith Group interviewed by Annie Fletcher,” in Otolith Group: Xenogenesis (Archive Books: Berlin, 2021), 19. |

| ↑4, ↑11, ↑13 | Ibid. |

| ↑5 | W.E.B. Du Bois, “An Appeal to the World: A Statement of Denial of Human Rights to Minorities,” published on Blackpast, May 3, 2011, https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/primary-documents-global-african-history/1947-w-e-b-dubois-appeal-world-statement-denial-human-rights-minorities-case-citizens-n, online. |

| ↑6 | As Adom Getachew outlines brilliantly in the book Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination. |

| ↑7 | “Artists Space Dialogues: Ciarán Finlayson and The Otolith Group,” Artists Space, published on YouTube.com, May 6, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RwzUzv07Rjw, online. |

| ↑8 | “Instant Ancestry: A conversation with The Otolith Group’s Kodwo Eshun and Anjalika Sagar,” Maysles Documentary Center, YouTube.com, November 14, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6J80iZicCpY, online. |

| ↑9 | Eshun, 228, cites: Siemon Allen, “The Image of South Africa” NEWSPAPERS: A Project by Siemon Allen, (Anderson Gallery Drake University, 2004), 21. |

| ↑10 | Eshun, 224. |

| ↑12 | “Artists Space Dialogues: Ciarán Finlayson and The Otolith Group,” Artists Space. |

| ↑14 | “Let’s Talk: On Asian Futurisms with Kodwo Eshun, Anjalika Sagar, Heri Dono and Anita Dube,” Kochi-Muziris Biennale, August 31, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bFplnCgbnMQ, online. |

| ↑15 | Denise Ferreira da Silva, “On Difference Without Separability,” in 32nd Bienal de São Paulo: INCERTEZA VIVA (Living Uncertainty), eds. Jochen Volz, Julia Reboucas, and Isabella Rjeille (São Paulo: Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, 2016), 57–58. |

| ↑16 | Quoted by George E. Lewis in “The Idea of Eastman: The Otolith Group’s The Third Part of The Third Measure,” in Otolith Group: Xenogenesis (Archive Books: Berlin, 2021), 343. |