Liv Bugge: The Consequence of Touching Oil

Liv Bugge, Goliat, Draugen & Maria (screenshot), 2021, film, 4K video finishing on HD Video, stereo sound, sculpture and AR installation, 23 minutes [photo: Marte Vold; courtesy of the artist and Volt, Bergen]

Share:

Oslo-based artist Liv Bugge’s video Goliat, Draugen & Maria (2021) opens with a close-up of a small glass bottle filled with dark viscous liquid. A pair of hands turns it about between curious fingers. An off-screen voice explains—in Norwegian, with English subtitles—that the bottle contains a sample taken in 1997 from a particular oil field in the North Sea. The voice’s tone is informational, pitched low as though to a small group of people seated inside a room. The voice instructs the person holding the bottle to “just feel [the liquid] and pass it on.” The person on whom the shot centers dribbles a small amount of petroleum onto one fingertip. “I’ve never given oil a chance to rub into my skin before,” admits another voice, as the liquid spreads and pools in the creases that line their palms. Earlier, a person comments that the oil smells good, like “all these things from childhood, actually. Like lawnmowers, and fathers with little canisters of oil.” The shot changes from the image of oil spreading across skin to archival footage from a film, probably shot in the 1960s or 70s, during the start of a very lucrative period of oil exploration on the floor of the Norwegian continental shelf in the North Sea. Two slim men in blue worker’s overalls are boxing on the deck of an oil rig. The camera focuses on them, on their dancing, their playful fighting. The film speed is slightly faster than normal, distorting their movements. Frenetic and boyish, they have an unconcerned air, yet they are imbued by the film stock and the pace with an edge of charismatic competition characteristic of adventure stories. The surface of the sea rolls in the background, opaque and full of possibility.

“Within the industry,” another participant explains, speaking about the oil industry in general terms, “there is a sense of ‘What do we need to reveal, and what can we get away with not revealing? And, also, how much do we even need to understand?’” The oil is just “down there,” she observes, in a parody of the industry’s mindset. It need only be gotten up from the depths. Although she is speaking from the perspective of companies responsible for the drilling, her comment is also suggestive of the Norwegian public, who benefit directly and indirectly from five decades of exploitation in some of the world’s largest underwater oil reserves. Since the 1990s, Norway’s central bank has also carefully invested oil revenue to maintain a financial buffer against market volatility. Consequently, the nation’s welfare benefits have been virtually guaranteed into the foreseeable future. The imperative to not contemplate the experience of oil is collective; everyone in Norway—including all those people’s children, present and future—is implicated.

Liv Bugge, Goliat, Draugen & Maria (screenshot), 2021, film, 4K video finishing on HD Video, stereo sound, sculpture and AR installation, 23 minutes [photo: Marte Vold; courtesy of the artist and Volt, Bergen]

The woman’s words are illustrated by a different archival film sequence, this one depicting oil barrels lashed together into a kind of honeycomb, suspended from a crane, and hoisted into the air. The sea behind this conjoined form is dazzling, the long rays of the setting sun glancing off the water’s mobile surface. For a moment, the honeycomb bundle is silhouetted by a luminous sea: figure and ground, oil and water, steel barrels and steel cabling. A mythical image of industrial romance.

Like any romance, there comes a moment of reckoning with the less ideal aspects of the love object. Sometimes attachment itself is toxic. In such cases, to understand the experience of the other, in a profound sense, requires owning one’s own capacity for violence, as well as the destructive nature of one’s own unwillingness to know. The voices in Bugge’s film confront this toxicity, this unwillingness to know, head-on. The camera centers on a woman in middle age with short-cropped hair and eyes the color of the sea, gray blue. She reads from her own notes about her experience with the oil coating the skin of her hands: “We don’t know how to quit you. We don’t know who we are without you. We are scared to find out who we are, and how … maybe small? … and powerless we are. Without you.” Her tone is searching and grave. Enormous political questions of petrochemical dependence and the way oil production has enmeshed Norway’s economy in suicidal global economic momentum are expressed as desire, loss, fear, abandonment, and self-knowledge.

Liv Bugge, Goliat, Draugen & Maria (screenshot), 2021, film, 4K video finishing on HD Video, stereo sound, sculpture and AR installation, 23 minutes [photo: Marte Vold; courtesy of the artist and Volt, Bergen]

The film’s opening sequences and the off-camera voices come from a listening session of the type Bugge has employed in her work informally since 2006. Participants are asked to sense and communicate nonverbally with animals and inanimate substances, and then to relate the insight gleaned from those nonverbal experiences in a group session. In 2014, as part of her doctoral work in artistic research and practice at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts, Bugge underwent formal training in the method. She describes it as a

practice that involves looking not only with your eyes but with your whole body …. After a meditation that grounds you, you are able to enter into a conversation on a telepathic level. Visualization in different ways is useful to get the conversation started. Then, during the conversation, deep listening, feeling, and seeing is the main goal.

Bugge conceives of these sessions as moving in parallel to theorists Donna Haraway and Karen Barad’s work on diffraction. These writers theorize diffraction as a nonlinear, historical record-making method. “Unlike reflections,” Haraway writes, “diffractions do not displace the same elsewhere, in more or less distorted forms, thereby giving rise to industries in story-making about origins and truths.” Haraway proposes diffraction as a visual alternative to objective methods that privilege rational thought, arguing that “diffraction can be a metaphor for another kind of critical consciousness.” Bugge brings this idea into her practice by refusing to “mirror” inanimate objects—such as trilobites, in her PhD project, or unrefined oil, in Goliat, Draugen & Maria—with her body. Instead, she organizes situations in which she, and others, can open up their perception from their bodies and diffract the discourse of objects or substances. In Structural Magic (2019), a book based upon her doctoral research, Bugge writes,

These sessions serve the purpose of being exercises in non-linear ways to relate to historical existences and concepts of time, as well as using my body as an image-making apparatus. The exercise also allows us to imagine a collective circulation of images and experiences; a shared knowledge and information.

What is the consequence of touching oil—of coming to know it in an embodied sense? What gets destabilized when oil slips out of the category of the inhuman, even momentarily? To make an image with the body requires revaluation of the discursive function of touch. I propose that Bugge’s document of people touching oil and becoming aware of its aliveness, its animateness, awakens those people to the violent relationship humans have not only with oil, but also with the world beings that humans broadly consider inanimate.

Liv Bugge, Goliat, Draugen & Maria, installation view, 2021 [photo: Marte Vold; courtesy of the artist and Volt, Bergen]

The camera settles upon a woman wearing lavender pendant earrings, made to resemble large feathers, that move slightly in the room’s air current. The woman is still, her eyes closed, her hands clean and resting lightly on her thighs, as if she is in meditation. She appears to be in her late 30s or early 40s. Her straight, dusty-brown hair is cut with slanted bangs that brush the tops of earnest-looking eyebrows. This carefully dressed, thoughtful woman seems to value sincerity, but she also understands the value of bright colors. It is surprising to hear a voice—probably her voice—on the voice-over track as the camera pans slowly across her sleeveless shirt, which is vividly-patterned in tones that match the lavender feathers framing her face. She says she can feel the safety of the oil’s enclosure in rock, followed by “the silence and then the trauma of extraction, and the vibration.” She is relating an experience of existential disorientation as the oil is evacuated from the seabed and pushed up, up, into the sky. There is discomfort in her voice. Some minutes later in the film, her voice returns, this time played over archival footage of waves lapping against the concrete pylons that hold the oil rig in place:

The thing about being down in the rock, and then … being kind of penetrated? In terms of the extraction method … because of the drilling and the vibration. There is a moment of trauma, and everything is shaking. And I know that feeling, because I have heard it described by people protesting against fracking …. I was sympathizing with the oil. This experience of this forcing in and forcing out again. The violence of the extractive moment … is quite amazing.

Another woman interjects that in North Sea fracking, as opposed to what’s occurring inland, they pump seawater into the underground reservoirs that used to be filled with oil to maintain the integrity of the continental shelf. The first voice, the woman amazed at the violence of the process, responds that this technique must mean that thousands of microscopic organisms in the water must also find themselves suddenly cut off from open sea, buried alive in the oil’s former gravesite. A pause follows as both women seem to contemplate this consequence.

Liv Bugge, Goliat, Draugen & Maria (screenshot), 2021, film, 4K video finishing on HD Video, stereo sound, sculpture and AR installation, 23 minutes [photo: Marte Vold; courtesy of the artist and Volt, Bergen]

“Are you going to let us kill ourselves by setting you on fire?” asks the women with short-cropped hair and gray-blue eyes, the camera once again centered firmly on her solid figure and quiet but searching expression. “Or are you a kind of witchcraft that we can contain by other forms of rituals than burning? ’Cause we have used you to extend our lives, and extend our power. Do you like being violated? Should we violate you again, or are you going to fight back? Is this you fighting back? What we’re seeing?”

Liv Bugge, Goliat, Draugen & Maria (screenshot), 2021, film, 4K video finishing on HD Video, stereo sound, sculpture and AR installation, 23 minutes [photo: Marte Vold; courtesy of the artist and Volt, Bergen]

Liv Bugge, Goliat, Draugen & Maria (screenshot), 2021, film, 4K video finishing on HD Video, stereo sound, sculpture and AR installation, 23 minutes [photo: Marte Vold; courtesy of the artist and Volt, Bergen]

Bugge’s work doesn’t respond directly to the woman’s interrogation of oil, but it offers a scene that parallels her testimony. It shows archival footage of an oil-spill clean-up. The specific spill is unnamed; given the sources listed in the credits, though, I assume it to be in Norway, during the early period of oil exploitation. A child’s hand, extended toward the camera and toward his mother, is smeared with oil. The child wears swim clothing. The setting is outdoors, perhaps on a beach. The child may have been in the water, or maybe just playing on the rocks. He has come back to show his mother what he has got on his hands. The mother rubs frantically—again, in part because of the film speed—but manages only to spread the oil more completely across the skin of the boy’s forearm. The shot changes before anything about this child’s fate is conveyed. I read this passage as an admission that the violence inaugurated by the oil rig—its extractive technology—is infinite. The child here figures as the human capacity to imagine the future, and the consequence of oil un-homed, violated, for this child and everything he represents are unknowable.

During the course of our correspondence about this text, Bugge sent an excerpt from Canadian poet Dionne Brand’s book A Map to a Door With No Return (2001). It is a complex work, but the piece Bugge sent focuses upon spatial problems for those who seek an impossible return to a sense of belonging that was lost during the Atlantic slave trade. Return is impossible because the maps were drawn by people whose sole ambition was extraction. Slave traders and the companies that employed them never made a spatial language that encompasses the possibility of return for those considered nonhuman or inanimate. For Brand, this spatio-linguistic impossibility is the philosophical inheritance of the Atlantic slave trade. In the introduction to the book, she writes:

To the Door of No Return, which is illuminated in the consciousness of Blacks in the Diaspora there are no maps. This door is not mere physicality. It is a spiritual location. It is also perhaps a psychic destination. Since leaving was never voluntary, return was, and still may be, an intention, however deeply buried. There is as it says no way in; no return.

Brand is not suggesting that the diaspora lacks direction in an objective sense, but that there is no schema to structure its members’ wayfinding. Their ancestors were violently extracted from a frame of reference, thereby disabling the construction of a schema capable of supporting a way back. The same is true for oil, as figured in Goliat, Draugen & Maria. No loop exists in which oil might leave the ground and then settle back into it, once whatever task it had been called forth to achieve was completed. As Brand describes for the enslaved, Bugge illuminates the fact that there are no mental schema for oil that allow for the possibility of return to the sea floor. There is only extraction, transport, and then consumption until extinction.

Liv Bugge, Goliat, Draugen & Maria (screenshot), 2021, film, 4K video finishing on HD Video, stereo sound, sculpture and AR installation, 23 minutes [photo: Marte Vold; courtesy of the artist and Volt, Bergen]

Bugge sent Brand’s writing in response to a correlation I made (during a seminar in March 2022) between the broad scope of her artistic practice and the theoretical work of geologist and philosopher Kathryn Yusoff. In A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (2018), Yusoff argues that the discipline of geology was developed in tandem with the transatlantic slave trade. The discipline’s function, in Yusoff’s view, was to make the natural world knowable and to mark a clear distinction between animate and inanimate. This distinction could be used as the foundation for one between human and nonhuman life, as well as for further distinctions between different humans, in terms of their agency. Thus, a logical spiral was built that could accommodate the extractive needs of settler colonialism.

For Yusoff, as for Brand, the problem lies in the mental schemas that geologic epistemologies—the theories that constitute valid knowledge in the field of geology—made possible. The way geology defines materiality, or the way it establishes how knowledge about the earth as material is validated, produces a kind of mental structure. This structure is like a navigational map for understanding the stuff of the earth. For Yusoff, the structure of valid knowledge in geology is grounded on a basic (and flawed) division between living and nonliving material. Humans are alive, rocks are not. This epistemological split “facilitated the divisions between subjects as humans and subjects’ prices as flesh (or inhuman matter).” Geology drew a map with a crucial error in thinking about the binary division of the world, and that mistake grew into a justification for the objectifying of human beings. People became objects of enslavement, and so it was unnecessary to think about trading maps with their return in mind. Non-agentive life does not belong somewhere to which it might make a sensible claim of the right to return. Brand argues that this status is true for the enslaved; Bugge represents the realization that it is true for oil.

Crucially, Yusoff is not arguing that geologists, political activists, and artists need to make the earth appear more intelligible by anthropomorphizing it, or causing it to appear more clearly in our own human image. Rather, Yusoff calls into question all the ways that the maps are drawn, or the organizational rules for the language games played by those in power:

The attachment to writing with and against a social geology is not to “humanize” geology so much as it is to understand how the languages that already reside within it are mobilized as relations of power—and how a different economy of description might give rise to a more exacting understanding of geologic materiality that is less deadly (by refusing the routine brutalities of economies of extraction and the legacy of colonial asset-making through geology).

Such a narrative, in Yusoff’s view, “refuses this account of the earth and its subjects as units of economic extraction” by changing the language of world-making or by opening to the many perspectives that are excluded by “the enlightenment project of liberal individualism.”

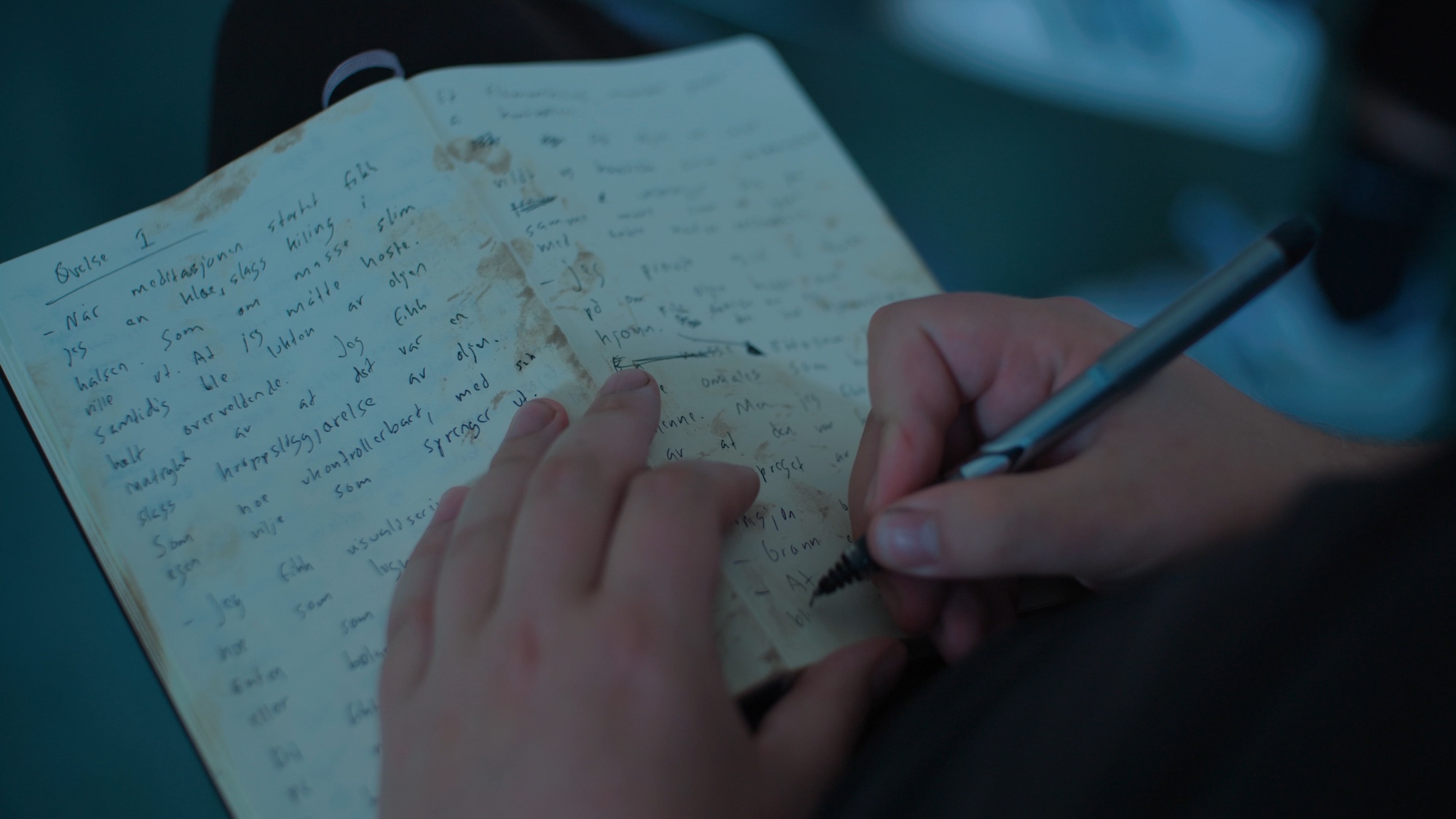

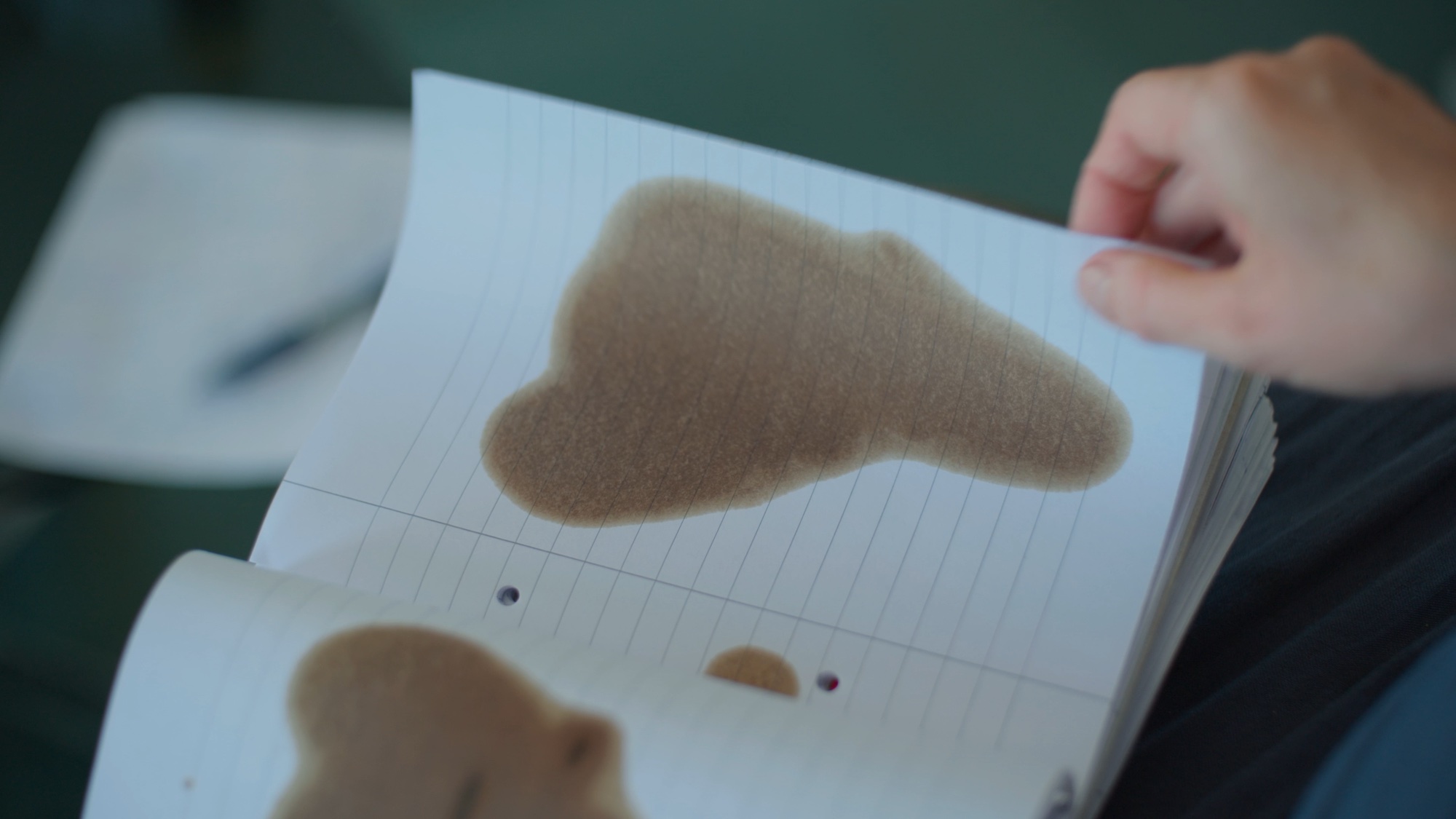

In a scene near the middle of the film, a woman describes how the sensation of raw oil on her body makes her cry, without any further emotional information attached to her reaction. As she speaks, a pair of hands is shown flipping through a ruled notebook, spiral bound. At the center of the page is a large oil stain that has bled through to mark the other pages. The hands flip the pages, slowly at first, as if the brown mark’s shape is being read. As the hands turn the pages more rapidly, the shape shrinks. It slowly disappears as the presumptive reader moves farther from the inscription event, through layers of ruled notebook paper. Finally, there are just a few light brown spots on the page, and then nothing. Once the notebook surface appears clear of oil residue, the hands tear out the first blank page, as if freed to take notes again on this fresh surface, to create language again with ink rather than with oily stains. This filmic passage contrasts the language of oil—its staining, seeping mark on the paper’s surface—with language in straight lines, the language of notation and ordered, sequential thoughts.

This passage in the film—and other moments like it in Bugge’s broader body of work—brings the limitations of language into focus. Goliat, Draugen & Maria demonstrates how easy it is to slip into familiar tropes—adventure tales, the collective libidinal investment in children as symbols of the future, the language of human emotional dependency and conflict. The means at our disposal—our language, our maps—prove paltry tools for fleshing out the consequences of our toxic relationship to oil, particularly when faced with the aftermath of the enlightenment project of liberal individualism. Bugge constructs a situation that admits a different kind of language, an embodied communication technique, but the limitations remain. The viewer, still, is left with the image of oil’s writing on the surface of a lined notebook. This gesture is consistent with Bugge’s syntactic choices throughout the video. The images from archival films stay centered on the oil rig and its machinery; very few are landscape views or show people outside the working environment of the rig. The listening sessions’ participants sit in chairs inside a room, wearing everyday clothes and taking notes on cheap paper. Bugge does not place the body as an image-capturing device into a radical situation. She does not, for example, shoot the film on an oil rig, or in a skiff on the North Sea during a storm, or depict anyone diving into the cold water. The ordinariness is intentional, I think. Bugge is interested in picturing a structural shift in how we use language and grant it authority. To capture that shift in a legible way, she relies upon existing frameworks. Bugge’s work—like Brand’s and Yusoff’s—addresses a limitation in the representational frames available to make marks of sense that can communicate an experience of historical time in the present.

Liv Bugge, Goliat, Draugen & Maria, installation view, 2021 [photo: Marte Vold; courtesy of the artist and Stavanger Art Museum, Bergen]

Natasha Marie Llorens is a Franco-American independent curator and writer based in Stockholm, where she is a professor of art and theory at the Royal Institute of Art. Llorens regularly contributes art criticism to art-a agenda, and she has recently published with frieze, CURA., Contemporary Art Stavanger, and La belle revue, among others. She holds a PhD in modern art history and comparative literature from Columbia University and an MA from the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College. She is currently at work on a book project about five experimental films from the 1960s/1970s in Algeria and collaborating upon a research project on 1970s Algerian socialism in the 1970s in collaboration with contemporary artist Massinissa Selmani.