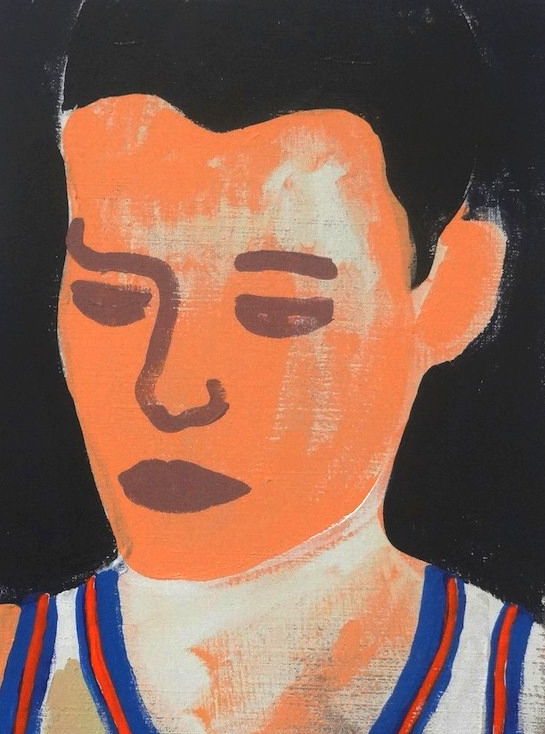

Andrew Kuo, “Tallboy,” 2012, acrylic on linen, 20 x 16 inches [courtesy of the artist]

LINSANITY

Share:

Jeremy Lin was deadpan, holding the home jersey of the Brooklyn Nets like a white flag. On July 20, 2016, the Brooklyn Nets introduced Lin as their new point guard and set to earn $36 million for the next three years—a good deal in the National Basketball Association’s current financial climate. He’s no stranger to New Yorkers, having made a memorable mark as a Knick, but the faint note of fatigue in his voice was new: he talked about the disappointments and lessons learned in the last four years as if he weren’t once the most famous athlete in the world.

Three different teams, a “poison pill” contract, and a constant din of criticism later have made it hard to remember that Lin appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated twice, Timemagazine once, and when he hit his signature game-winning shot versus the Toronto Raptors, you could feel everyone in New York City scream in unison.

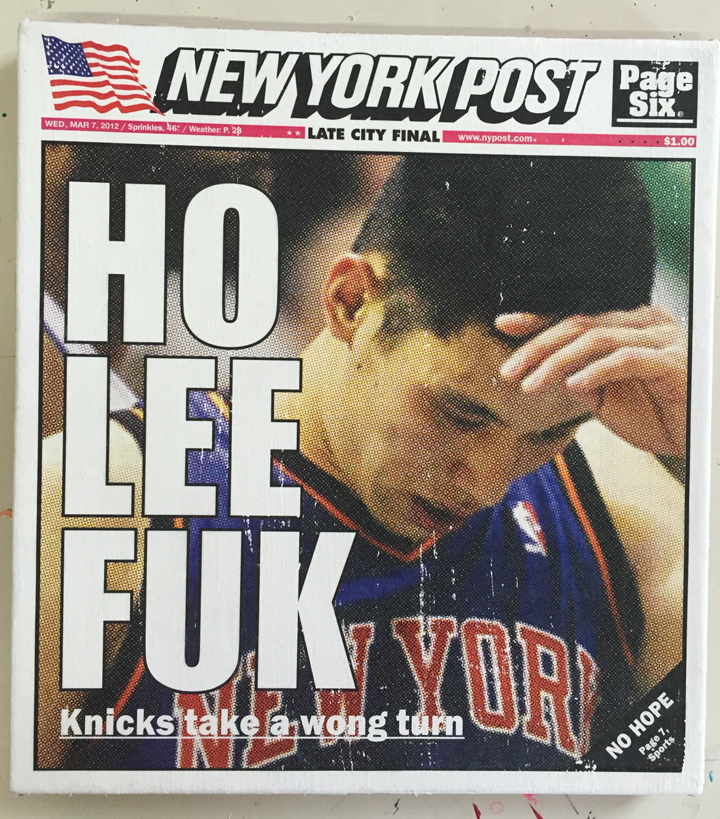

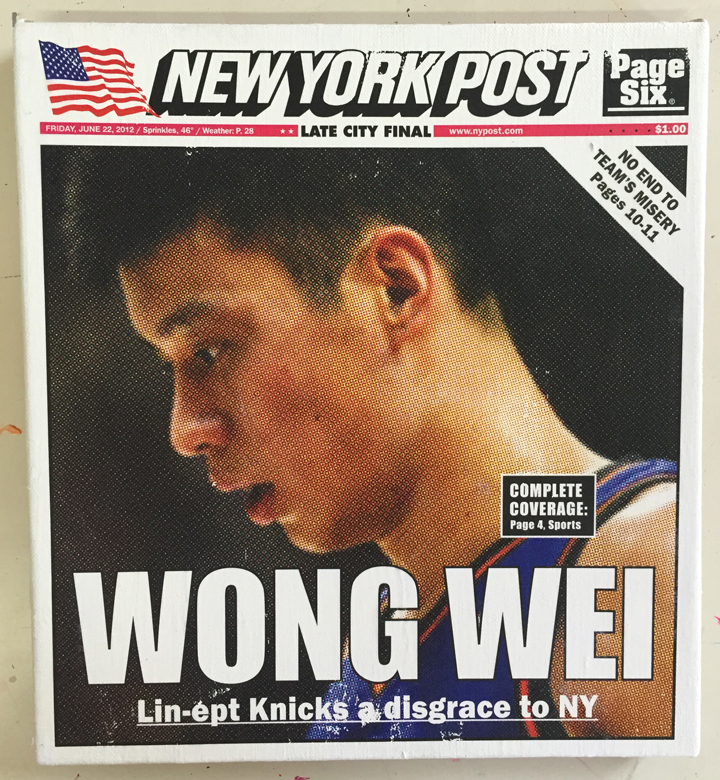

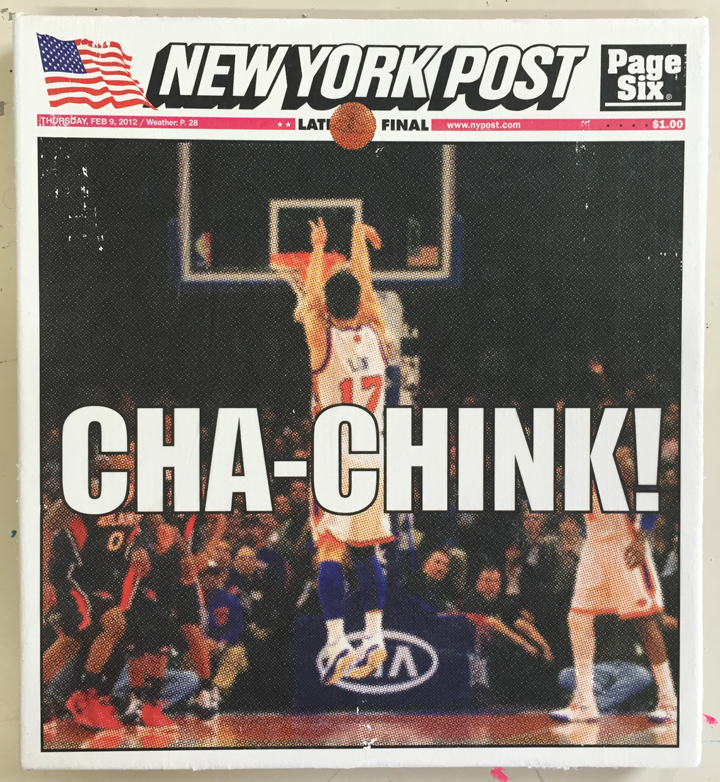

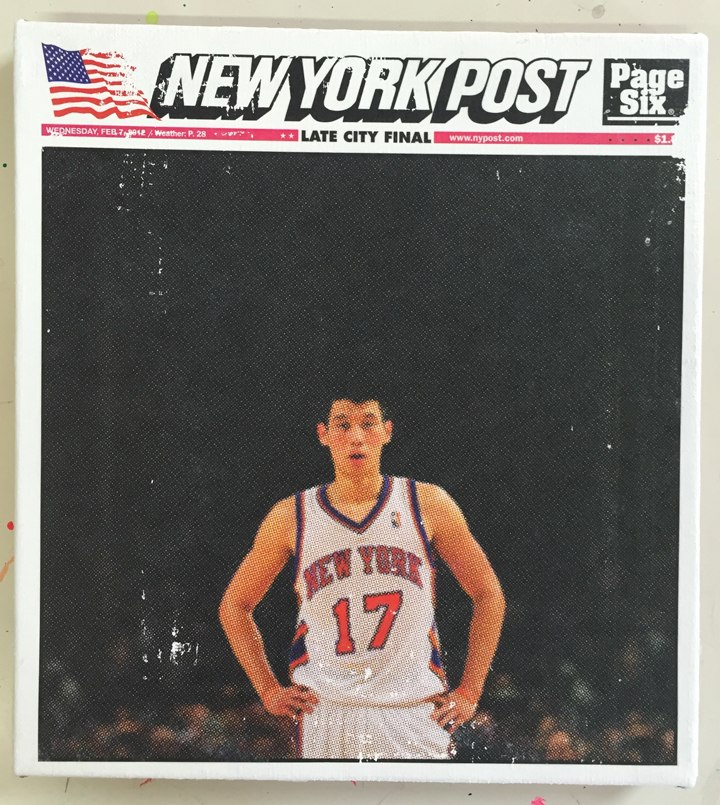

Andrew Kuo, Linfinite Jest, 2014, manipulated newspaper cover [courtesy of the artist]

Andrew Kuo, Linfinite Jest, 2014, manipulated newspaper cover [courtesy of the artist]

In the 13 years after their outrageous run to the finals in 1998-1999, the Knicks had managed only a total of four winning seasons. Years of unfortunate decisions by upper management had saddled the team with a perpetually high payroll and no moments or future to show for it. At the bottom of their organization, Jeremy Lin, who’d almost exhausted his opportunities to crack the NBA after stints with the Golden State Warriors and Dallas Mavericks, was claimed off waivers as backup insurance behind Baron Davis, Toney Douglas, and Mike Bibby. The 2011-2012 Knicks were an underachieving group of stars, has-beens, and filler. Thanks to lingering injuries sustained by Davis, teammate Carmelo Anthony suggested to head coach Mike D’Antoni that he give Lin a chance in an early February game versus the New Jersey Nets. Lin exploded for 25 points and handed out seven assists in a come-from-behind win against All-Star point guard Deron Williams. “He got lucky because we were playing so bad,” D’Antoni said. If basketball gods actually exist, they had blessed a languishing team with an injection of raw tenacity. Lin ripped through the next 25 games with unbelievable shots, fearless drives to the basket, and moments of poise—a budding star. The Knicks roared in a way that brought back memories of John Starks, Latrell Sprewell, and Larry Johnson, when the team felt like it mattered. But as the playoffs neared, Lin suffered what proved to be a season-ending knee injury. The Miami Heat promptly eliminated the Lin-less Knicks in the first round 4-1, and it was over. Glen Grunwald, the team’s general manager, insisted they’d bring back their electric guard, but we knew there was at least a chance we’d seen the last of him in New York.

Fans who recall Linsanity talk either about a young basketball player on the cusp of relevance or about an aberration. Entering this season, Lin’s player efficiency rating, a per-minute summary of a player’s positive and negative accomplishments, is 15.1—right at the NBA average of 15. But critics point out the three-year, $25-million deal Lin accepted from the Houston Rockets as an example of a lesser player cashing in on short-term success: $14.8 million of that offer was due in the third and final year, which is how it earned its “poison-pill” tag—a detail that gave the Knicks an excuse to let him go. It’s easy to fault New York for not having matched Houston’s offer. Maybe Anthony was eager to reclaim his team, but it’s more likely that the team just didn’t think Lin was real—after all, what Asian-American Harvard graduate had ever become an NBA-caliber talent?

Andrew Kuo, Jeremy Lin, 2013, acrylic on linen, 16 x 12 inches

[courtesy of the artist and Marlborough Chelsea]

Fans who recall Linsanity talk either about a young basketball player on the cusp of relevance or about an aberration.

To some, Lin is unfairly treated because of who he is and where he comes from. In April, Hsiu-Chen Kuei, a 48-year-old NBA fan from San Jose, CA, produced a six-and-a-half minute YouTube video called “Jeremy Lin: Too Flagrant Not to Call.” In it, Lin is repeatedly mauled by defenders who nonetheless sidestep any flagrant foul calls. Kuei said, “It’s not about views. I didn’t get money or anything. I didn’t want attention. I just want Lin to get fair calls.” (As of August, the video had been viewed almost 2 million times.) Is Lin a victim of racial bias? Lin himself has never openly criticized officials, and the NBA’s response was purely scientific: they presented evidence that Lin had drawn common fouls at the seventh-highest rate among the 23 players with more than 1,500 drives. (Lin drove to the basket 1,537 times.) The NBA “found no data that suggests Jeremy Lin is disadvantaged by our officiating staff.” But what Kuei was talking about wasn’t data—she was talking about how she felt.

Kurt Warner went, proverbially, from night stock clerk to Super Bowl champion, underdog Buster Douglas beat a troubled Mike Tyson against all odds, and John Daly won the 1991 PGA Championship after barely even qualifying—but none of these athletes was Taiwanese-American. The height of Linsanity was also open season for jokes—there was that ESPN.com headline that read “Chink in the Armor,” and the New York Post‘s “AMASIAN!”, not to mention a market for T-shirts that depicted Lin as a kung fu master. It all suggested that it was okay to portray Asians as mostly polite but nimble martial arts sidekicks, or as masters of some sort of Eastern basketball sorcery. In 2002, on the night the Houston Rockets drafted Yao Ming first overall, a grainy video from Shanghai fittingly showed Yao awkwardly muffing a hi-five. His role was that of an exotic physical anomaly—someone from a different planet, where elegant basketball player robots stand seven feet, six inches. His success sparked a trend of copycat hires, but the Wang Zhizhis and Mengke Bateers came and went. The scouting reports always seemed to say the same things, noting players’ “lack of toughness” or calling them “passive.” But public perception of Jeremy Lin suffers from the same thing that makes superstar Stephen Curry so popular: he’s about as tall and as big as the rest of us are. One benefit of the data-driven response is that numbers can help us see beyond what our eyes might tell us: Asians, especially ones who are not seven feet tall, can play professional basketball, and Jeremy Lin’s stats have proved it.

Through all the Knicks’ brainlessness, they’ve always been my team, and I’ve never been a luckier fan than I was during Linsanity. I remember pushing back tears—from happiness and sadness—as he ran into the arena to a euphoric crowd’s greeting. Years of growing up in this body, in this place, seemed to rush to the surface of my skin. I thought about what my mother and father had to do to get to this country, to live and work in New York and to have their grown son cheering and hoping, all for a Chinese kid.

Andrew Kuo, Linfinite Jest, 2014, manipulated newspaper cover [courtesy of the artist]

Andrew Kuo, Linfinite Jest, 2014, manipulated newspaper cover [courtesy of the artist]

Andrew Kuo is an American artist, born in 1977 in Queens, NY. Kuo is a painter, sculptor, and a contributor to The New York Times.