Kenneth Tam: The Silence We Hold Between Our Bodies

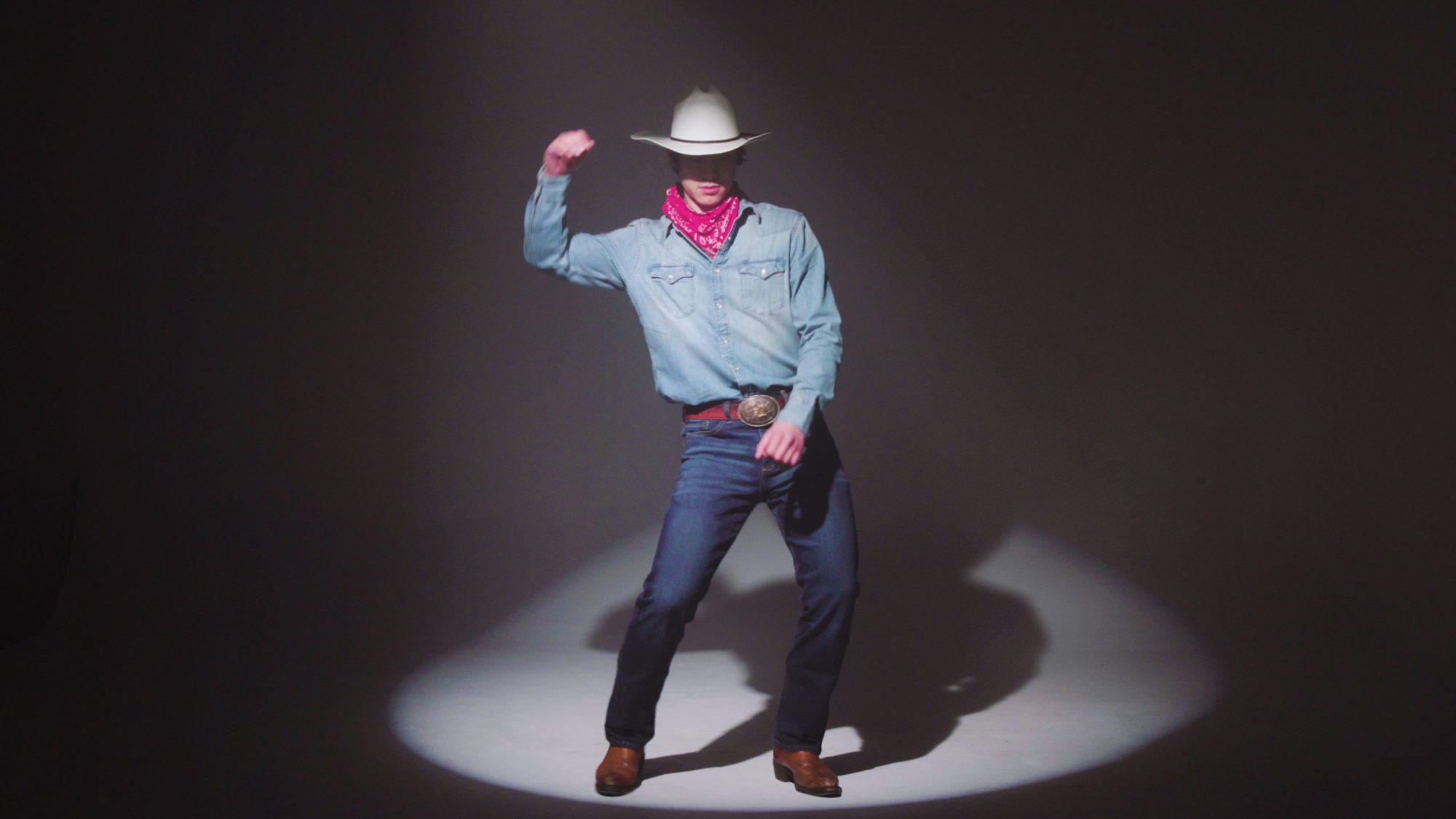

Kenneth Tam, Silent Spikes (still), 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

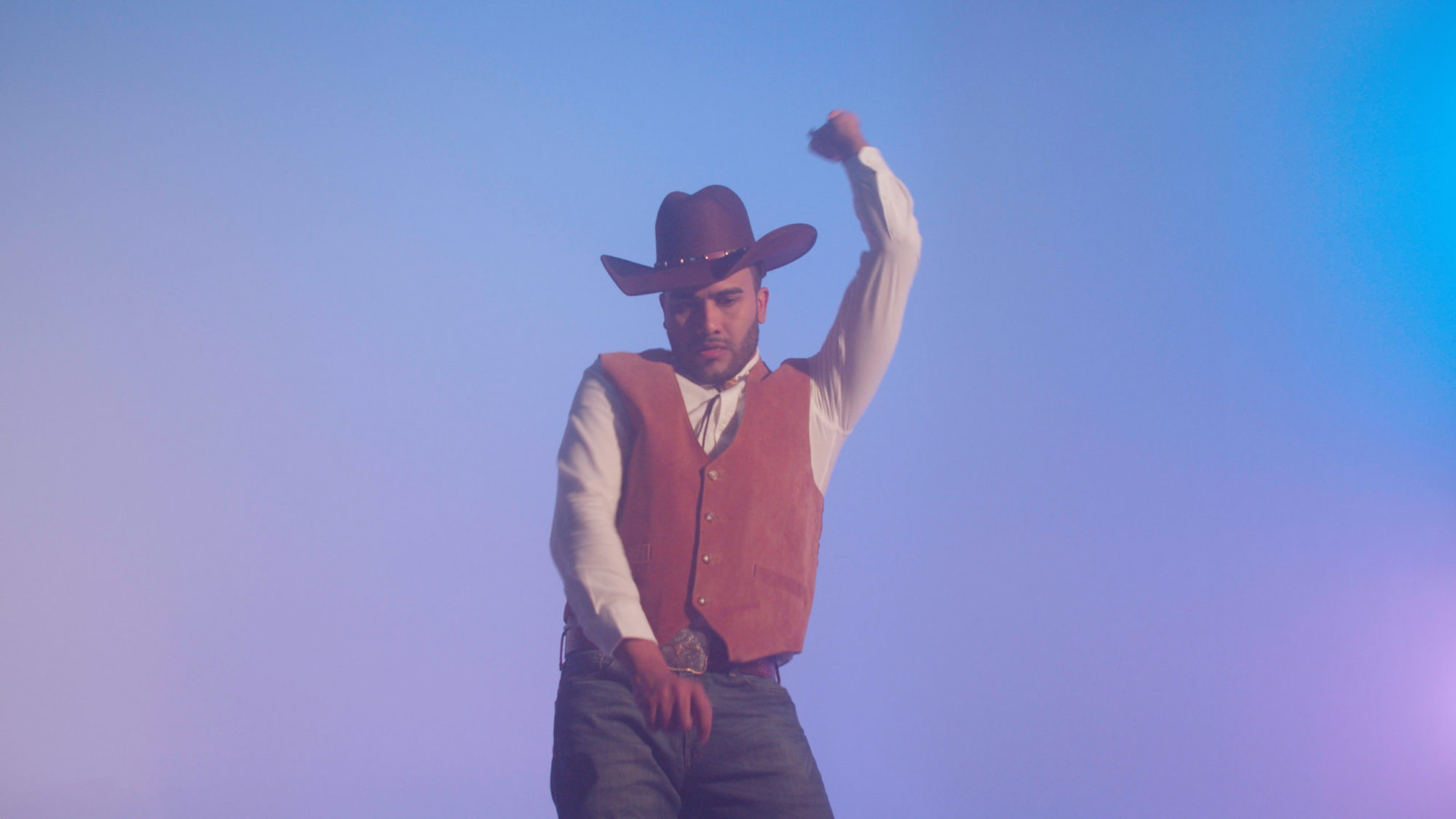

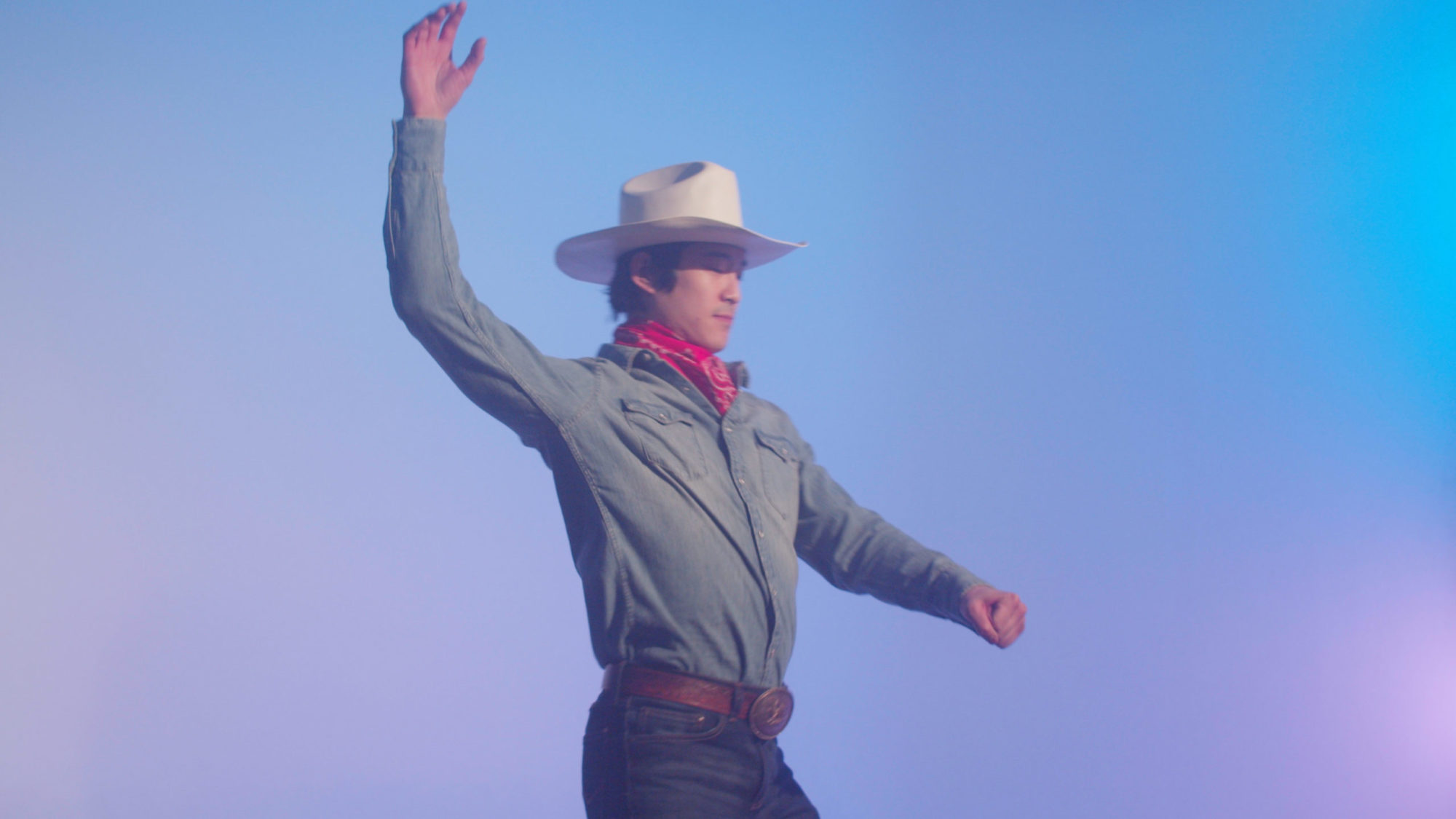

Public and private rituals have long been at the center of Kenneth Tam’s practice. The particular rituals that draw his eye are those that shape normative notions of male identity, which he reimagines through playful yet uncanny videos, sculptures, photography, and choreography. His recent work Silent Spikes (2021) reflects upon the intersections of race, labor, class, and masculinity through a transtemporal narrative. The two-channel video installation takes as its point of departure the history of Chinese labor on the Transcontinental Railroad, a body of scholarship that has been largely under-represented. Tam pits this history against a classic trope in American pop culture, the cowboy—the lone hero, the wanderer, the self-imposed outsider. As visual and textual references evoke the narratives of Chinese laborers in the Old West, Tam interweaves contemporary subjects to connect past and present. A diverse group of Asian American men “perform” as cowboys through surrealistic vignettes set against a neon-hued, dreamlike background.

Tam’s cowboys likewise engage in deeply personal conversations about intimacy, sensuality, insecurities, and relationships. These moments convey a level of vulnerability and comfort that often evades typical portrayals of masculinity and homosocial spaces. These vignettes also contrast with the quintessential image of the cowboy, a figure embodying prototypical masculinity and the essence of US isolationism. But a different kind of isolationism exists within the diasporic experience: the feeling of exile imposed upon the immigrant, the refugee, the other. In collapsing disparate temporalities—past and present, real and performative—Tam explores the potential of masculinity’s softer forms, the lineage of Asian American identity as a construct, and, as one subtitle from his video reads, a “companionship born from solidarity.”

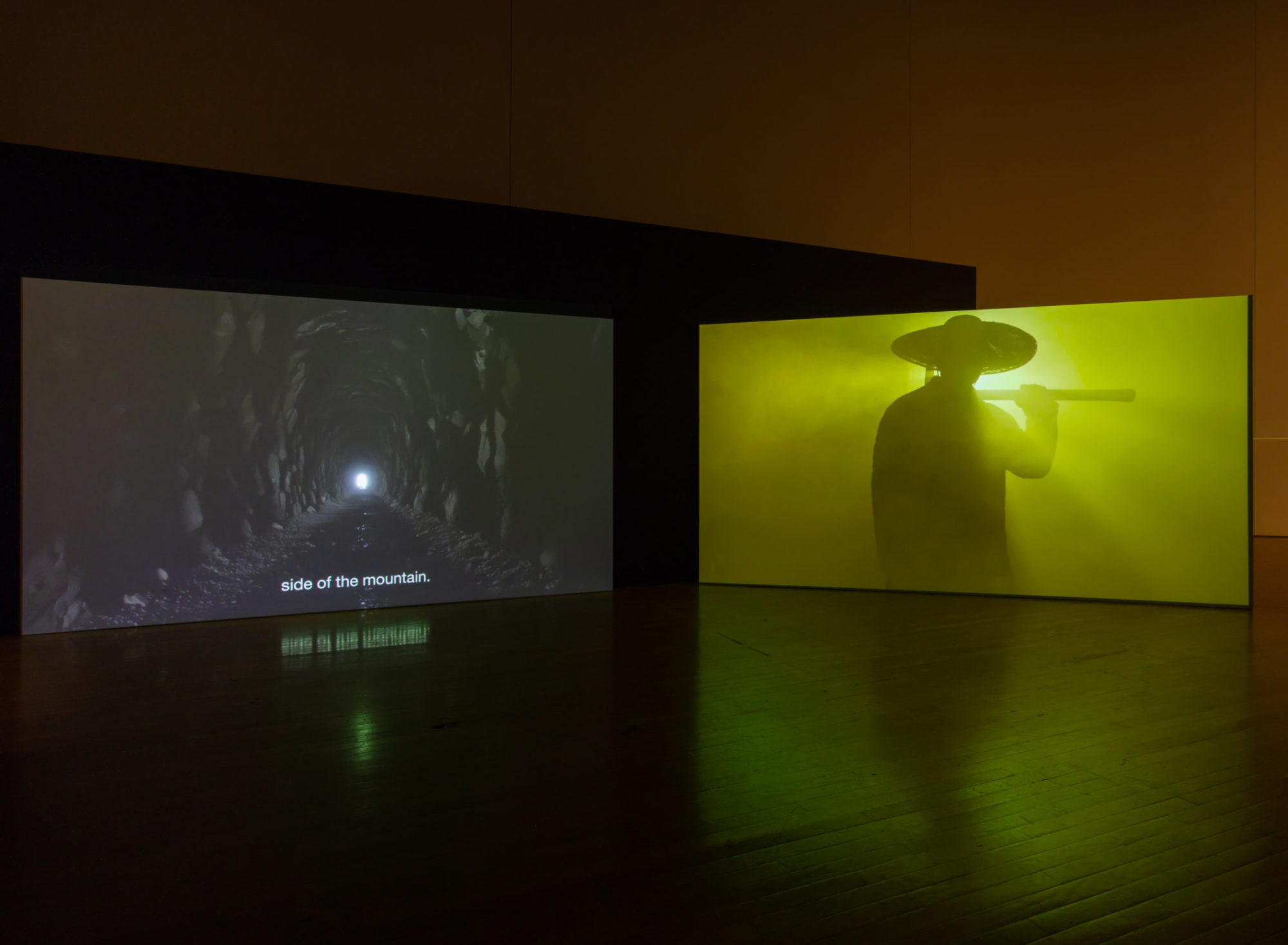

Kenneth Tam: Silent Spikes, installation view, 2021 [photo: Jason Mandella; courtesy of the artist]

Re’al Christian: I’d love to start with your recent work at the Queens Museum, Silent Spikes, which is a really beautiful installation. I’m curious to know how you came to the source material, the book The Silent Spikes: Chinese Laborers and the Construction of North American Railroads [Huang Annian, 2006], especially.

Kenneth Tam: The book came as a result of research on the subject matter of the Chinese laborers working on the Transcontinental [Railroad]. There’s really not a whole lot of scholarship solely devoted to that subject. Recently there has been renewed interest, I think because it was just the 150th anniversary of the Golden Spike, [which marked] where the eastern and western halves of that project met, so there was [an] impetus to generate new material and refocus academic research on it. But that book, The Silent Spikes, came out before [the anniversary]. It was actually written by a scholar in China, so it’s a different perspective altogether …. But the show itself came about through wanting to work with a group of Asian American men and to think about what Asian American masculinity could look like.

In previous projects, I’ve been working in this way of finding groups of men through online postings who didn’t necessarily have any particular relationship to one another. They weren’t of a particular racial background, or class, or anything like that. I knew … I wanted to focus this next project on a particular group that I felt was lacking in representation, certainly, in the art world. But even the subject of Asian American masculinity seems perhaps “not so cool” to investigate.

I came up with this project, thinking about my relationship to images of hegemonic masculinity when I was growing up. I remember when I was in high school, I was taking these painting classes, and [among] my favorite subjects to paint were the Marlboro men, if you remember those—the iconic images of cowboys smoking. And that figure has always sort of stuck around in the back of my mind. And I was wondering what would happen if you had an Asian man take up that role—you know, don the costume, what would that mean? Would that complicate things? Because that figure does not exist in popular culture. So, thinking about what does it mean to have an Asian American cowboy, is there a way to assume that role? Asians [were] already in the West, but their histories were excluded, and forgotten, marginalized, which then led me to research the Transcontinental Railroad and the history of using immigrant labor.

RC: I’m interested in the role of time in your work, and how your pieces look so contemporary and even futuristic, but, like you said, you are collapsing different temporalities and creating very contemporary subjects and figures that are deeply rooted in the past, and [are] very much informed by these historical legacies of labor, of masculinity, of assimilation.

Kenneth Tam: Silent Spikes, installation view, 2021 [photo: Jason Mandella; courtesy of the artist]

I like the reference to the Marlboro men because in Silent Spikes, and also in another work that you did, All of M (2019), you have these groups of men, in homosocial spaces, performing for the camera. So I’m interested in how you think about photography and its role in indexing the past, and if you’re interested in the myth of the truth behind the camera.

KT: I think this is really the first project where it has a strong historical component. Even then, working with a group of self-identified Asian American men and [histories of] the Chinese laborers in the West—that’s not necessarily a one-to-one relationship, right? There’s a lot that’s different between those groups. But at the same time, I feel like there is something about their struggles and the challenges … they experienced that certainly continues to this day. I thought drawing that link was important. In the video itself, the image of the tunnel becomes this sort of wormhole between the past and present. That voyage through physical space, I thought, was also a metaphor for the struggles that Asian Americans and Asian men have had to deal with [while] existing in this country, and being recognized as—I don’t even want to say citizens, but legitimate participants within this country. There’s so much of that history that also involves the way they have been exploited, they have been denied citizenship, denied the rights of others. So I thought that was important to hint at, if not explicitly, [to] at least suggest this bit of history.

In terms of photography, I’m definitely very interested in this idea of performance—the way we perform ourselves for a camera, but also for each other. I think that we are using internalized scripts that are based on things like our gender, class, racial identity, occupation. The way that we construct identity also carries with it information [about] how we should carry ourselves, perform ourselves. So, in each of these projects that I take on, I’m interested in investigating how male subjects perform themselves, perform their maleness, or express their maleness, particularly in groups … where that sort of thing happens most explicitly: this unspoken consensus [through] which men operate when they are in a group situation.

You brought up All of M, and I think, certainly, I was interested in the American prom as a vehicle to investigate these ideas of male performance, and part of the prom is about these cheesy photoshoots that happen, and I thought that was an interesting opportunity to have my participants explicitly perform themselves …. There’s a certain vulnerability that can be expressed in those situations where the performance is not quite right. It’s like they know what it should be, but they’re not able to pull that out on command quite yet.

RC: There’s a similar moment in Silent Spikes where you have four men standing in front of the camera and … you have one of the men, like you said, struggling to perform this particular prompt, this particular notion of masculinity like the rest of them. It’s interesting how that kind of identity formation starts so early.

KT: Definitely. The prom is an interesting coming-of-age ritual, and one of the reasons I was drawn to it is its inherent theatricality. You have these adolescents who get to dress up and sort of play adults for one night, and it’s fascinating to see that happen, and to see what they imagine being an adult looks like or feels like. Even if it’s just putting on a cheap suit, there is some sort of information that is being codified within that ritual, and so much of that particular ritual is based on the gender binary …. All that performative, unspoken scripting in a space like the prom is something that the ritual reinforces, and that’s something that I was investigating in that performance … I staged at The Kitchen [The Crossing, 2020], which was drawing from the ritual of a very specific social space.

Kenneth Tam: Silent Spikes, installation view, 2021 [photo: Jason Mandella; courtesy of the artist]

RC: I’m interested in how The Crossing and another piece, The Glass Ceiling (2020), contextualize fraternity rituals specifically within diasporic communities, where perceptions of masculinity are often shaped by the felt experience of being the other in a hegemonic society.

KT: I’ve never really been interested in fraternities before. I think there was something [laughs] almost distasteful about the way—obviously they’re these super male-intensive homosocial spaces, but I didn’t find that to be particularly interesting until I started to learn more about these Asian American fraternities and the way in which they use ritual to negotiate identity, to negotiate ideas about assimilation, and certainly about the performance of the male body, but doing so [in a way that] tries to express some idea of Asianness, even though it’s completely muddled and at times lost, while also reconciling their adolescence. It was interesting to do more research about fraternities that perform these rituals, and to see how much they borrowed from African American fraternities—looking towards them for guidance, or at least trying to replicate some of the things they saw in those spaces and adopting it for themselves in a way that I think is, perhaps, a gesture not just of recognition but also understanding [of] how Black frats use those rituals as a form of empowerment and identity construction. These Asian frats, whether they are conscious of it or not, were doing much of the same thing. The paradox—or the contradiction, really—is that in search of rituals, in order to give their own identity meaning and cultural richness, they all sort of forget that their own cultures carry—are built upon—thousands of years of ritual and cultural knowledge. That’s the sort of negotiation … I was interested in seeing: what they chose to assimilate in their own identity, what they borrow in order to craft their own sense of selves, at least in a group. And the performance that I put on [at] The Kitchen, The Crossing, was an attempt to give form to that negotiation through movement.

Kenneth Tam, Silent Spikes (still), 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

Kenneth Tam, Silent Spikes (still), 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

RC: I like your point … about the act of appropriating aspects of white fraternities for groups associated with Asian American males and Black Americans, but I think in striving for recognition … of male identity, there’s this caveat that arises when hypermasculinity becomes the only way to express one’s gender and one’s personhood. It becomes a way of defining the self and asserting a certain dominance or strength at the sacrifice of vulnerability and intimacy …. I think there’s an element of violence in the rituals, especially in the fraternity rituals that comes out in these works … that are ultimately about violence inflicted on Asian men.

I was curious to know how you saw the relationship between these histories, these stories, or testimonials, and your materials. You have these really metaphorically rich works—installations, and sculptures, and videos, and choreographed performances—but aesthetically they are very sparse and minimal. I was curious about how materials allow you to tell enough of the story without relying on … seeing these acts of violence play out in these communities.

KT: I definitely knew that, while I wanted to address the violence, there’s a very real violence that happens in these Asian frats. But the symbolic one that is part of this negotiation, part of creating any identity, also involves forgetting or losing or destroying other things. So I knew I wanted to touch upon those elements without necessarily reproducing [them] for an audience …. The Crossing is really an attempt to merge an initiation ritual—a fraternity initiation ritual—with a Taoist funeral, so the whole thing is also a meditation on grieving and how one expresses that, especially in a time, now, during the pandemic, when there’s so much death and grieving happening. But we aren’t really able to do that publicly. I feel like we, as a culture or society, are not truly able to deal with death or the act of grieving, at least publicly or as a cohesive body. So it was interesting to have to engage with that subject, even in a metaphorical space, as a performance or theater—

Kenneth Tam: Silent Spikes, installation view, 2021 [photo: Jason Mandella; courtesy of the artist]

RC: —Well, like you said, spaces for grief are just so limited. There is greater solidarity and validation, and a collective sense of mourning that, unless you belong to a marginalized group of people, you’ve maybe never experienced before—that collective sense that we’ve lost something as community …. But I do wonder how … we’ll be able to actually grapple with this traumatic moment, and if we’ll be able to reconcile the lack of responsibility that we’ve had for one another… in the past and [the] present.

KT: I think what we’re doing, or what we’re seeing right now, is sort of an immediate desire to move on from this, even while it’s happening, right? This very public, concerted effort to look … beyond the pandemic, and forget [it] while we’re experiencing it. I think American culture is really good at that—the one thing we sort of excel at is the simultaneous experience of annihilation of history in service of, I don’t know, in service of just moving on and continuing this fiction that we tell of ourselves ….

But I guess this sort of ties into what I’m trying to do—unearth some of these histories, or at least try to, with Silent Spikes, create these parallels, because, even as an Asian American person, as a Chinese American, I don’t personally feel like I can identify with the laborers—the Chinese laborers. There’s sort of a disconnect with the Asian diaspora, because of immigration, because there’s this lack of continuity between these generations of people coming over. I think, for most people, it’s hard to make these links, and to see these waves of migration as interlinked, as interconnected, and I think part of this project is trying to see that we are all on the same continuum. These struggles are not new, these struggles are not isolated; they have been happening for a long time, but we think that, with each generation, all these things we’re experiencing are new and unique to our own generation, but it is certainly not that way. So, that was something … I wanted to express with Silent Spikes and the visual metaphor of the tunnel. You know—being in this thing that can perhaps connect … disparate locations in time and space, the West and the East, the past and the present.

Kenneth Tam, Silent Spikes (still), 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

Kenneth Tam, Silent Spikes (still), 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

RC: One of my questions was about the tunnel and how it acts as this rupture within the video … which has moments of surrealness and humor and intimacy—platonic intimacy between these men …. There’s this quote by bell hooks that “the diasporic is an act of will and memory.” I’m interested in how, even as a Black American, I still feel very disconnected from my cultural past … and I like the idea of the tunnel acting as this interlocuter between different temporalities.

KT: I think that’s a really great point … you make, and that’s also a way I’m drawn to ritual, specifically the way in which these Asian American fraternities—the whole term Asian American is a bit nebulous, right? It encompasses so much. It really was an invention, but this is an invention that has weight behind it. I think, for a lot of these young men who do end up being in these fraternities, there is this sense of displacement or not being able to be located [in] one particular community. And rituals: They can perpetuate histories and cultures, but they can also reimagine or invent new ones. I think that, for these young men who join these fraternities, it’s an attempt to create new cultures and new histories for themselves … taking certain things from different parts of their identities and cobbling together something new, and using ritual … to give it form and to give it weight. I think that, for children of immigrants who don’t have a connection to wherever their parents are from … it can be very disorienting. I think ritual can be used in this very productive way to mark identity. And I try to use that, too, as an artist, to also use ritual to reimagine the identities of the people … I work with.

Kenneth Tam: Silent Spikes, installation view, 2021 [photo: Jason Mandella; courtesy of the artist]

RC: There’s this concept in performance studies … surrogation, as an act of reimagining or re-enacting an imagined cultural past, as a way of embodying a cultural, historical, familial legacy. I think that rituals definitely play into that. On the theme of rituals and violence, I wanted to circle back to the sound component in Silent Spikes, and how the music … progresses and slows and builds tension over the course of this video, and how it directs you to which screen to look at. But I think that silence is also an integral part of your work. The music builds this tension, but there are these moments of punctuated silence in Silent Spikes, in The Crossing, and then another piece you did, sump (2015), with your father, where you’re re-enacting these seemingly arbitrary rituals in a close domestic setting. I’m interested in the comparison between these types of silences. There’s the silencing of bodies due to violence or erasure, there are moments of silence that we give [in remembrance] to those [whom] we’ve lost … and then there are the familial silences—the generational traumas that go unarticulated.

KT: I really, really appreciate the work you do to tie that all together, because I chose to work—in that video sump you mentioned—with my father because I think that our relationship is one primarily based on silence. We communicate through silence, in nonverbal ways. Not necessarily through gestures, but we communicate by not communicating, if that makes sense. I think that is something … not unique in Asian American families, particularly between one generation that was raised in this country and one that came from Asia. There is this sort of gap, especially in my own experience with my father, growing up. While he was a presence in my life, he was also inaccessible to me, and so I used sump as an opportunity to investigate that gap, that silence, and to see if the invented gestures, the invented rituals, can somehow engage him in a way that I could not engage him through acts of speech, for a number of reasons.

Kenneth Tam, Silent Spikes (still), 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

I’ve always been interested in how the body can communicate, not necessarily in an aesthetic way, but through intimacy, through vulnerability, through the absurd, through humor. These are all things that I choreograph with my father in that video as an attempt to investigate the silence that we share, that we hold between our bodies. And that certainly exists, this idea of silence as a metaphor for forgetting, for the exclusion of certain histories. It’s definitely something that’s referenced in Silent Spikes, but also in the ways in which silence—you know, I was interested in that kind of image, too, of “silent spikes” that I reference from the book. These individuals, who were seen as docile or easily exploitable, can also come together and find solidarity and resistance, too; the silence, this perceived silence, is actually a misreading of something else.

So much of Silent Spikes was an attempt to embrace qualities of male expression that are typically stigmatized or seen as taboo. So many of the acts or gestures are about embracing vulnerability or sensuality as a way to perhaps upend hegemonic masculinity, these ways in which men are instructed to behave and perform around each other …. Asian men can complicate that performance through the embrace of vulnerability and intimacy with each other, and in doing so, try to subvert the image of the cowboy—this sort of long-held, cherished icon of American masculinity, or White masculinity …. I think there’s something about … investing in the bodily, the sensuous. The sensual can be empowering.

***

This interview originally appeared in ART PAPERS Summer 2021 // Speculative Masculinities.

Re’al Christian is a writer and art historian based in Queens, NY. Her work has appeared in Art in America, ART PAPERS, Art in Print, BOMB, and The Brooklyn Rail. She has contributed texts to recent and forthcoming publications by CUE Art Foundation, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., and the Hunter College Art Galleries, where she is a curatorial fellow. She is an MA candidate in art history at Hunter College, and she earned her bachelor’s degree in art history and media studies from New York University.