Katherine Jentleson: Whose History of American Art?

William Doriani, Flag Day, 1935, oil on canvas [courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection]

Share:

Curator Katherine Jentleson joined Atlanta’s High Museum of Art in September 2015 as the institution’s inaugural Merrie and Dan Boone Curator of Folk and Self-Taught Art. The High began collecting artworks by self-taught artists forty years earlier, in 1975, and in 1994 it became the first major American museum to form a department dedicated to the field. Among the department’s most significant holdings is the largest collection of works by Nellie Mae Rowe, an African American self-taught artist who spent the last three decades of her life dedicated to making drawings, collages, hand-sewn dolls, and other artworks in her home in Vinings, Georgia, just outside Atlanta. She elaborately adorned nearly every available surface of both the interior and exterior of the building, often referring to it as her “playhouse.”

This fall, the High Museum is presenting two concurrent exhibitions organized by Jentleson. Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe [on view through January 9, 2022] is the first major exhibition of the artist’s work in over twenty years, positioning her practice within the historical and cultural context of the decades following the civil rights movement in the South. A second exhibition, Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-Taught Artist in America [on view through December 11, 2021], explores how artists such as Horace Pippin and “Grandma” Moses were received and understood in the early and mid-twentieth century, laying the groundwork for how future generations of self-taught artists—including Nellie Mae Rowe—would be recognized and acknowledged.

Jentleson spoke with me over the phone, illuminating the research and personal reflections that have shaped both exhibitions. The transcript of our conversation has been edited for publication.

Grandma Moses (Anna Mary Robertson Moses), Black Horses, 1942, oil on Masonite [courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne, New York, and Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York]

Logan Lockner: Could you speak generally about the development of each of these exhibitions? I am curious to hear about how Gatecrashers grew out of your doctoral dissertation, whereas [the work of] Nellie Mae Rowe came into your purview when you joined the High in 2015.

Katherine Jentleson: Yeah, Gatecrashers grew out of the research that I began as a doctoral student at Duke University. I went back to graduate school expressly for the purpose of writing this dissertation—which would become my book, and this exhibition—because I had been wandering around New York for a while attempting to teach myself about self-taught artists. I was a journalist and wanted to tell the story in a different way. I wanted to do more in-depth research on how these artists first started receiving recognition from the mainstream art world early in the twentieth century, which I found fascinating. In my experience, that narrative was not part of the story of art in the twentieth century, period. I was finding out all these interesting tidbits of information, like that William Edmondson, this amazing artist from Nashville, was the first African American artist to have a solo show at MoMA [The Museum of Modern Art in New York]. Or that John Kane made it into the Carnegie National in 1927, which was maybe the only major international contemporary art event happening in the United States at that time. These kinds of historic appearances really fascinated me, and I wanted to learn more about the artists behind them and the circumstances that surrounded their entry into the art world.

Horace Pippin, The Buffalo Hunt, 1933, oil on canvas [courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and Scala/Art Resource, New York]

KJ (cont.): I wrote my dissertation on John Kane, Horace Pippin, and “Grandma” Moses. There were so many other artists that fascinated me from this era, but the more I got to know the period and what happened, the more I got to see that these were the three artists who not only got the attention of the art world but really held it. They were [each] very widely celebrated: Kane starting in the ’20s, Pippin starting in the ’30s, and Moses starting in the ’40s. Through their stories, you can understand the bigger picture of this first wave of interest in self-taught artists. Even though I talk about other artists in my dissertation and in the book that followed, I kept it really tightly focused on these three case studies of their art and life, and how both folded into larger trends that were happening in American society and in American art.

LL: Even when we think about how vexed the term “outsider art” may seem, its usage doesn’t exist in a historical vacuum, and yet this history that you are talking about is not very well known. I’m curious about how this moment, and the reception that this first generation of self-taught artists received, relates to [notions of] what it means to be American and how those were being challenged and reconfigured at the time.

KJ: Absolutely. This is a major theme within my book and my dissertation, and I delve into it in the “Negotiating National Identities” section of [the exhibition] Gatecrashers. [The early twentieth century] is a time when the art world is still largely segregated. [But] that doesn’t mean there is not a ton going on, especially for African American artists, in this moment, because of the Harlem Renaissance and the New Negro Movement, and all of the groundbreaking surveys and texts that are being organized and published in that era. But you don’t really see any exhibitions of American art where Black artists and White artists are shown together, or White artists [with] other artists of color. So, first of all, [Black] self-taught artists [such as] Horace Pippin and William Edmondson were absolutely breaking the race barrier that existed within the art world by being shown within this category of self-taught art. This is, on the one hand, still marginalizing because, for example, in this era one of the terms that is used again and again by places like MoMA is modern primitive. So, it’s not to say that these artists were being shown in a way that didn’t still have some kind of colonial denigration of their identities and their perspectives as artists, but they were being shown at MoMA.

Grandma Moses (Anna Mary Robertson Moses), Sugaring Off, 1943, oil on canvas [courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne, New York, and Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York]

KJ (cont.): The other thing is most of the artists [in those shows], who we would now consider White, wouldn’t have been considered White in that era. They were recent immigrants who were coming from countries that, during the 1920s, faced some of the most restrictive immigration policies that the US made up until that point, particularly some countries in southern and eastern Europe. Many of these forces swirling within American society during the 1920s really constricted definitions of Whiteness and what it meant to be called an American. In the 1930s this started to change, and there started to be an opening toward a more multicultural approach to American identity, and terms such as, “the melting pot” came into usage.

Another thing that changed during this era was that the field of anthropology shifted dramatically, moving away from the kind of crazy pseudoscience of the previous century, where races were studied within these hierarchies, and toward cultural relativism, which was being put forward by people like Franz Boas and Ruth Benedict. In this period, Zora Neale Hurston also produced the first rigorous, important anthropological text on African American folk culture. A lot of previous ideas about different civilizations and races were being shattered within the world of academia, and that was trickling down to the art world as well. There were all of these shifts happening in views about Whiteness, about Americanness, about who can be counted in those ways, and I think that really did impact the way that self-taught artists were perceived in this moment.

When you look at an exhibition like Masters of a Popular Painting [presented at MoMA in 1938], even though, again, there were only a few artists of color, the vast majority of the White artists who were in the show were people who would have, a decade earlier, really struggled to be recognized as American. They would have been targets of racism and xenophobia—for being Jewish, for being Catholic, for being from Germany and Italy. Many of these self-taught artists were coming from ethnic and racial backgrounds that had not been previously counted and promoted as American.

Morris Hirshfield, Girl in a Mirror, 1940, oil on canvas [courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Estate of Morris Hirshfield/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society, New York]

LL: Could you speak a little bit about the term gatecrasher and [how] you adopted that term from newspaper coverage of these artists, rather than [from] art historical accounts? I’m also interested in how this notion of “gatecrashing” suggests independence and self-determination, which is another part of American identity. Although these artists might have been ostracized or challenged because of their racial or ethnic backgrounds, they’re also distinctly American in a certain way, in the sense that they are pursuing their own self-determined freedom of expression.

KJ: Yeah, that’s absolutely right. What I love about the term gatecrasher is that there is so much agency within it, and that is something that you see so clearly, especially in the trajectories of the three artists I focus on in my book, who are in the exhibition. But it’s also true for most of the artists in the show. They weren’t just sitting back and waiting to be discovered. They were proud of what they were making, in touch with their identities as artists, and [they were] entering their work into exhibitions.

This whole idea of [being discovered], and the passive role that some of these self-taught artists get cast into— [Although that is] sometimes [how] the dynamics unfold with an artist becoming known, by and large, self-taught artists are actually aware that they’re artists. They are aware that what they’re making is something of value, and they are actively putting it out into the world. That is part of why I like the term gatecrashers.

The other reason is because of what you said: it’s kind of ripped from the headlines. That was important to me because part of the point … is to reestablish that these were artists who were part of a national dialogue. They were being reported on in their local city papers and the national press.

The media couldn’t get enough of their stories, precisely because of some of what you mentioned: they had these very paradigmatic stories of beating the odds, of democracy in the United States working, where people who came from these humble backgrounds managed to find success as artists. There are tons of quotes comparing them to Horatio Alger and all kinds of American legends.

When I use gatecrasher, it’s not that I’m trying to say that we should be using this as a term that replaces self-taught art or folk art or self-made art. I’m not offering it as an alternative. It’s more of a salute to the widespread attention that they received in their own time and to the agency that they really held as makers of their own destinies.

LL: Some art historians have written about a particular Morris Hirshfield exhibition that took place at MoMA as this moment where the idea of self-taught art began to crystalize. Can you share a little about that story?

KJ: Morris Hirshfield was an artist working in Brooklyn. He came from [Poland], and he and his brother worked their way up in the textile industry in Brooklyn and managed to ultimately become very successful manufacturers themselves. Toward the end of his life, he couldn’t continue overseeing the factory, and began painting. Eventually he was included in a 1939 show that Sidney Janis curated. Janis was a trustee at MoMA and a major American art dealer who would go on to promote so much important American art of the century. After that show, MoMA acquired a bunch of [Hirshfield’s] work. In 1943, Janis curated an exhibition of thirty Hirshfield paintings that just got slammed in the press. Peyton Boswell, who was, at that point, the editor at Art Digest, published this review [with] a headline calling Hirshfield the “Master of the Two Left Feet.”

There was a lot of beef with MoMA among certain critics throughout the 1930s, [which] had nothing to do with self-taught artists. There was a lot of frustration that MoMA wasn’t concentrating on “the right” American artists, so self-taught artists like Morris Hirshfield became the scapegoat [for] that. What I really try to pull out in both the book and the show is that this was 1943, and “Grandma” Moses was only starting to get popular at that time, and she really became an issue for the American art world. She attracts so much vitriol from American critics and curators for the next decade, essentially, and that really starts to create this schism [around self-taught art] that you were asking about.

Nellie Mae Rowe, Untitled (Voting), before 1978, color photograph, crayon, pencil, and colored pencil on cardboard, 20 x 30 1/8 inches, [photo: Photo by Mike Jensen, Courtesy of Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York]

LL: Let’s talk about “Grandma” Moses and Nellie Mae Rowe a bit more. We know that it’s not just coincidence that these people didn’t start making art until later in life. It was the direct result of economic and other social conditions. Rowe and Moses both spent significant periods of their lives working as housekeepers in other people’s homes. It’s interesting, these overlapping connections across generations, and even across racial identities.

KJ: Moses and Nellie May Rowe [share a] common feature in their stories [in that] they were both women born to large families on farms, “Grandma” Moses in New York and Nellie Mae Rowe south of Atlanta, Georgia. They were both born into farm families, where you start working as soon as you can. I’m not sure how long Moses stayed in school, but for Nellie Mae Rowe, it was until she was around ten years old. By that point, her teacher had already identified that she had a great artistic talent and told her father [as much]. But there was just no possible way for her to dedicate time to that because so much was required of her, in terms of labor, from such a young age.

Although this exhibition is something that I have been working toward since I began at the High six years ago, the real heavy lifting took place in 2020, during the onset of the pandemic and the national trauma of the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others. All of that made me think about Nellie and the radical nature of what she chose to do at the end of her life as an act of self-liberation. It wasn’t something that she was doing privately. It was something that she was demanding visibility for. I already saw her work in that way, in some regards, but it really made me want to underscore just how much—even when her work isn’t explicitly referencing something social or political—it was coming from this radical act of self-definition.

LL: So much of Nellie Mae Rowe’s identity as an artist seems to be bound up in childhood, and girlhood in particular. Even this idea of transforming her home into a playhouse and making dolls—like you say, there is something much more radical contained within those gestures.

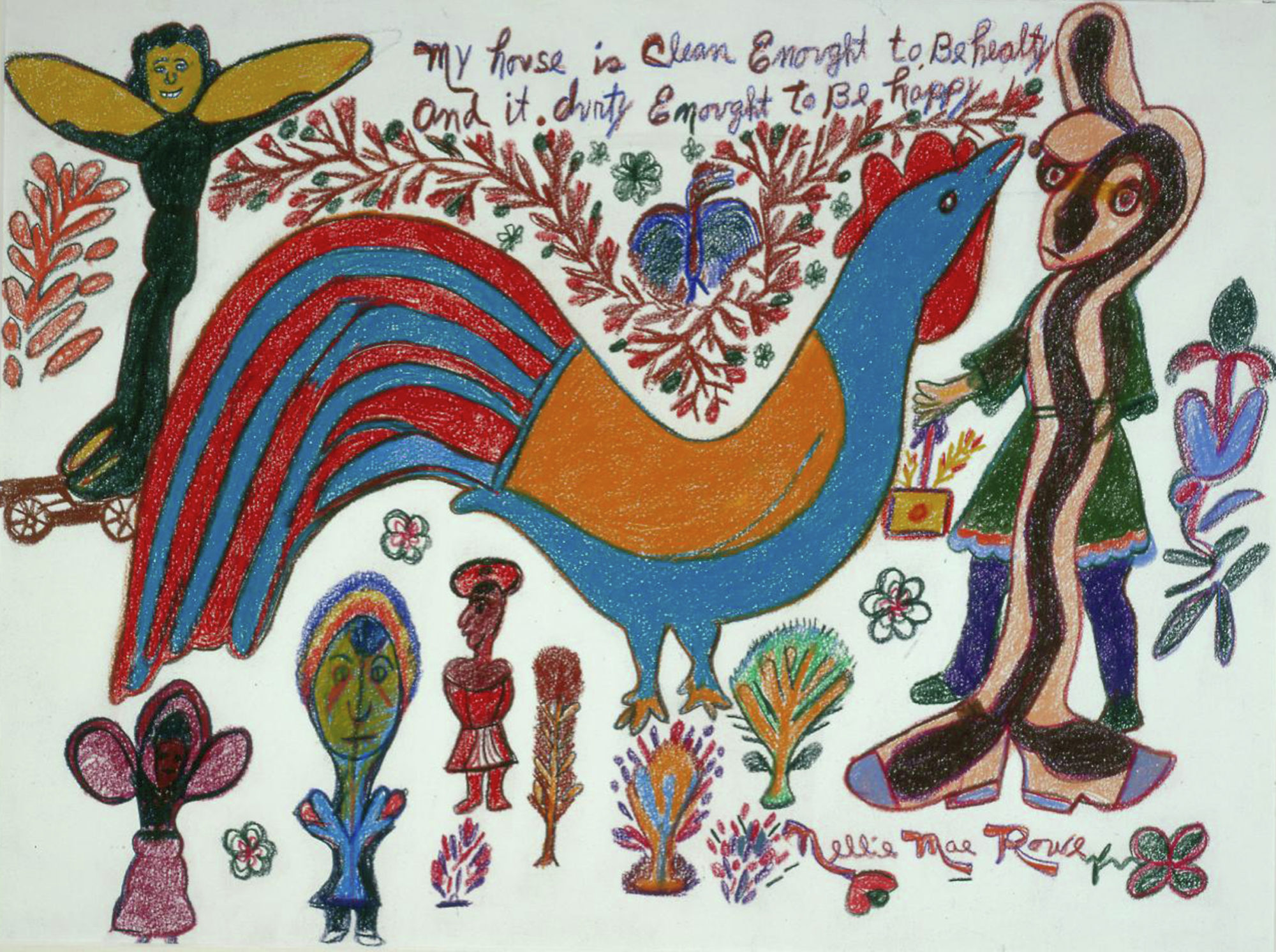

Nellie Mae Rowe, “My House is Clean Enought to Be Healty and it Dirty Enought to Be Happy,” 1978–1982, crayon and pencil on paper, 18 x 24 inches, [Courtesy of Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe and High Museum of Art, Atlanta]

KJ: Absolutely. Nellie Mae Rowe framed her return to artistry as a return to childhood, as a return to girlhood, because that is the last time in her life that she was able to experience that freedom…. She said, “I’m going to go back to my childhood. I’m going to go back to my playhouse. This is me playing.” That is how she spoke about what she was doing. But in a way, even though that message has always been received from her, it has [resulted in her not being] taken seriously. When a White male artist, such as Pablo Picasso or Alexander Calder, for example, frames their art in that way, it is seen as a radical revelation and choice, to acknowledge this state of creativity and knowledge that exists in so many children. But when a Black woman—Southern, self-taught, all of these things that can so often get marginalized within the art world—when she says it, it can get taken as a sign of naiveté, a sign of a lack of sophistication. But it was a very intentional return to childhood that, again, was a radical, sophisticated choice for someone who had been deprived, in many ways, of her childhood.

LL: Rowe’s visual style is so distinctive, integrating animal and plant forms with the human figure and creating intricate compositions and collages. As a curator and an art historian, how have you engaged with that style?

KJ: There is so much [scholarly] work left to be done on the incredibly layered and meaningful compositions that she created. [Previous scholars have] looked at certain animals, for instance, that reappear again and again in her work, like dogs or roosters or fish. There are all these different kinds of potential resonances between the animals, especially when considered in the broader context of what she was making. Something I’ve been interested in is this complexity in her work, the way that different entities are woven together—plants, animals, humans, architectures. For me, this is very related to her playhouse and the work she did with installation.

The second thing is how she shows human figures. Especially with the women in her work—who are probably, most of the time, some version of her. This is an act of feminism. This is an act of demanding that women be seen at all stages of life. For me, the fact that women are so visible in her work must be seen as a political act, as an act of demanding visibility for herself.

Logan Lockner is a writer in Atlanta. Previously, he was editor of BURNAWAY. His writing is included in the forthcoming monograph Toyin Ojih Odutola: The UmuEze Amara Clan and the House of Obafemi (Rizzoli Electa, September 2021).