Karen Holmberg: Archaeology in an Emergency

Share:

Vesuvius from the air, 2007 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

In part two of our conversation, Karen Holmberg discusses the seemingly intractable problem of convincing people that they are in danger, or helping them to see that the world is changing around them and encouraging them to mitigate, or prepare for, those changes. Holmberg studies how natural disasters were processed by prehistoric humans, who generated mythic explanations and created a vocabulary of symbols that allowed them to narrate devastating events, and to navigate the resulting traumas. Holmberg sees this methodology as a way to confront climate change denial and the looming volcanic crisis in the Naples region of Italy. Storytelling can be a fraught practice, particularly when it attempts to derive lessons from sometimes scant archeological evidence and to offer us information about the future. Part one of this conversation is available to read here.

Will Corwin: Humans have decided to move back to the exact place where they were in danger in Chaitén, [Chile]. What have people done in the past when a volcano erupts? How have they dealt with dramatic natural changes? Have they moved away? Have they come back?

Karen Holmberg: From both the Chaitén example—a 21st–century example—and then the prehistoric example in Panama [of] the Volcán Barú, the lessons that I would draw from those are when people are catastrophically affected and there’s a large loss of life, when fields are covered in a way that is not going to allow for recovery for years, they move—they leave. However, when there’s not a large loss of life, and when you can pick up [the pieces of] your life, you stay. But you never forget what you saw. There’s a lot of ink spilled [about] how we have this contemporary, very Western privileging of vision as a sense, and [of] sight. You can’t possibly tell me, however, that [seeing] a volcano—[one] that you saw day in and day out of your life—erupt, [would not stay] in [your] memory. The feeling, when the earth itself beneath you is moving and shaking. The sound—these are some of the loudest sounds you will ever hear as a human being, the loudest sounds of the universe, these eruptions. And the way that [prehistoric] human beings [tried] to convey these events that they experienced to people who [had] not experienced them, [tended] to be through art, rock art in particular. You want it to be permanent. In the prehistoric context, [permanence] is the most permanent thing.

WC: You mentioned the myth associated with the Volcán Barú—the pregnant [sea] with the frog. That’s a very feminine depiction of a volcano.

KH: That idea of a pregnant belly, growing and growing. This is a Bribri story. The frog, and the presence of God, and the sea was a pregnant woman. She was bitten by a snake, and she died. The frog was told by God to sit on her belly. The frog became hungry, saw a worm, and jumped off to get the worm. No matter what [the frog] did, she couldn’t get back on the belly again, which began to rumble and shake and make a very loud noise. Suddenly a tree burst out of the belly, shot up toward the sun, and then blossomed out. [The myth] can be pretty easily aligned with one particular eruption, in fact.

WC: When was that?

KH: It was around 200–300 AD—a very well observed eruption. The way you encapsulate it is through narrative. It becomes memorable, and you’re not going to forget any of those parts of that eruption that you witnessed because it’s a part of the story, right? You have a time depth, of how many days the magma chamber was filling, and that’s when the rumbling was going on, and then the eruption plume started. We do the same thing. We can only describe what’s larger than us or incredibly different from us through metaphor. Even scientists use analogies to the body to describe the volcano: Necks, toes, fingers; born, died, extinct.

Volcán Barú national park, 2021 [photo: Dr. Ariel Rodríguez-Vargas; courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

WC: You’re also doing work in Naples with [the] Campi Flegrei [volcano]—how is this situation different from the contemporary archaeology museum in Chaitén? The Campi Flegrei project is also about memorializing or interpreting recent history dealing with volcanic destruction.

KH: They’re both coastal, and they’re both contexts in which the primary need is to convey information about future risks, not just to memorialize past events. Making sure that people are well educated in what the risks are in [their] location. The vast difference is that Patagonia is a very sparsely occupied and remote area. In Naples, you’ve got upward of 360,000 people living inside [the caldera] of a potentially budding super volcano. You’ve got an exceptionally [highly] visited—prior to Covid—part of Europe. Naples has been on the grand tour for hundreds of years. How do you convey risk? And back to this concept of monumentality, … people were surprised that Chaitén erupted in 2008 because they did not know that Chaitén was a volcano—it was not common knowledge. However, it is monumental, and they can see it. If it starts to rumble or starts to smoke, you better believe they’re going to pay attention in the future.

The difference with Campi Flegrei is that it’s a caldera. That means it’s a flat, collapsed volcanic area, and a huge portion of it is underneath the [Gulf] of Naples. You have 1.5 million people living inside of a volcano in Naples. This means that while people who are living inside this exceptionally dangerous volcanic context know about Vesuvius—they can see Vesuvius, and they understand its monumental presence in the landscape—they’re not necessarily aware that underneath them, all around them, and in fact so large that they don’t even see it anymore—it’s that big—is another volcano.

WC: A bigger one?

KH: Yeah, a bigger one. It’s a challenge because, like [with] climate change, when something is so large, how do you convey [it] to someone without overwhelming them, or without them saying, “I don’t believe you—it’s not possible.”

WC: So how are you going about presenting this data in a way that will resonate with people?

KH: The Naples project is very new. It’s called “Warnings and Emergencies: Scientific Practice Informed by Community Experience” [WESPICE]. That is a newly forming project through University College London and local community groups in Naples, [using] scientific, predictive modeling of when something might happen. In 1970, there [was] a series of earthquakes, sometimes hundreds per day; it can happen in these types of seismic swarms. They’re very low-level earthquakes. [Naples is] this beautiful coastal area, and it wasn’t a wealthy community, and people were forced out. There’s a lot of ambivalence about “wait, are they just taking over our property?”

The film footage of the evacuation is shocking—think about what was going on politically, because this was 1970 in Italy—they sent soldiers with machine guns through the streets with loudspeakers telling people they had to leave. It was a very botched evacuation in terms of the fact that people felt that the scientists were arrogant, and there wasn’t coordination of scientific opinion [and] presentation. You had differing opinions going on. It was handled by the government in a very heavy-handed way, so there’s still bruising.

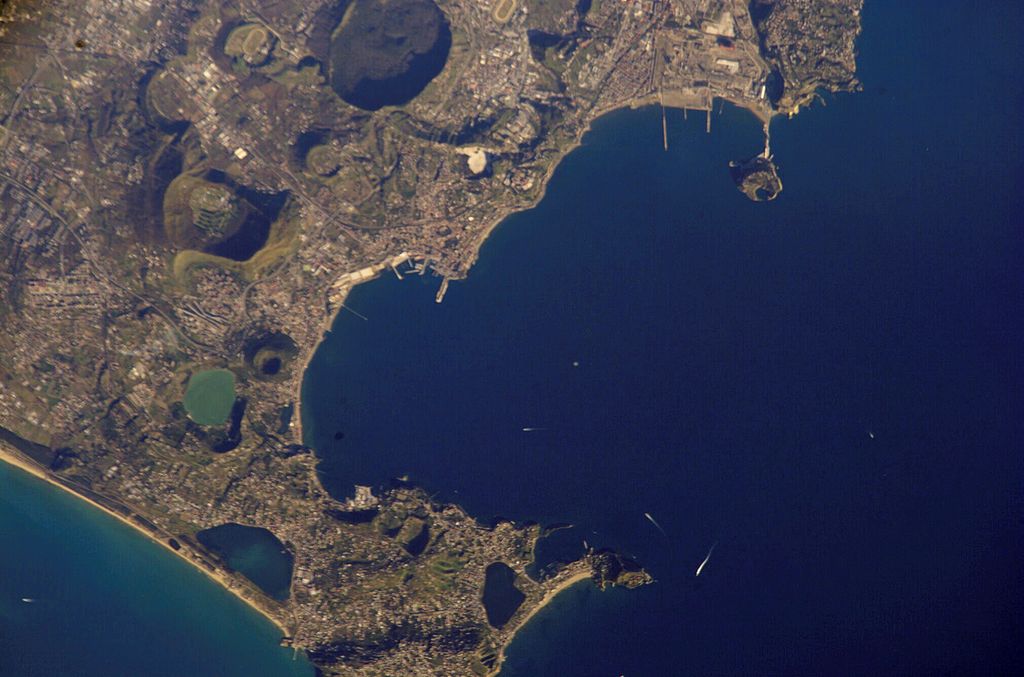

Astronaut Photography of Earth: Campi Flegrei and Pozzuoli, Italy, 2001 [photo: ISS Expedition 4 crew member; courtesy of Wikimedia Common]

WC: Did anything happen in the end, after the evacuation?

KH: No, and that’s a problem as well. Then [another evacuation] happened again in 1984.

WC: But should they not have evacuated [the people]?

KH: The communication needed to be done in a very different way. Yes, they should have evacuated [the people], but the problem is they were never allowed to go back. The government paid them a very small portion of what their property was worth. No, you shouldn’t have people living there, because it’s harder to extricate people when they live in that context—look at Chaitén. People want to go back to exactly where they were before, so there’s a danger in terms of evacuation. When something does happen, as it will eventually—give it time—at either Vesuvius or Campi Flegrei, the number of people who will need to be evacuated on very narrow roads is … daunting. So that’s the point of this project, WESPICE; [to] understand the scientific context and understand how you best convey things to people about these situations.

They’ve come again down to art, narrative, poetry, story, drama. This to me is the story of the little frog in Panama in the context of the Volcán Barú … several hundred years later. When the next volcanic eruption occurred, people could think back to the story of the little frog and have a context. It’s at least a means for understanding—you’re not going to control that natural event, but at least you’re going to understand it better. I think that’s a large part of [the problem with] climate change, isn’t it? The anxiety. We don’t understand what’s going to happen. The physical manifestations of climate change are going to be harsh. However, the anxiety is an added layer—the anticipation and the anxiety. At least when you understand things, and are able to convey them, you have a sense of maybe being able to figure it out. I don’t think we feel like we can figure it out. I think it’s one thing to intellectualize genetic bottlenecks—archaeologists do understand those.

WC: Genetic bottlenecks?

KH: That’s basically when most people die. The breeding population comes down to a very few pairs. Then it opens up again because the populations increase. We’ve had multiple genetic bottlenecks in [the history of] the human species. I think it would be a very different thing to live through a genetic bottleneck than it is to conceive of one in the past, I will say that.

Back to the little frog on the woman’s belly. We were finding these cobbles carved with little frogs, and in graves you find gold frogs. To me there’s an apotropaism there. It’s not just art, it’s “please don’t let anything bad happen.” This is environmental mitigation in a way. There’s a response, a creative response, that is born out of anxiety in these contexts. I think what we face [with climate change] has absolutely no analog in the past.

WC: But there have been events that have wiped out half the human population—

KH: Oh, more than [half].

WC: I don’t think people can get their heads around the fact that [a mass extinction event] could possibly happen again.

KH: No, I don’t think that people like to deal with that, because it’s too large, and because that sense of paralysis that you get, in that individual action can’t [respond to the scale of the crisis]. It shows you your lack of efficacy, if you’re like, “Oh, what can I do to change this?” I don’t care how much recycling you do in your household; you’re not going to transform the system. So that’s the discomfort.

That’s where the arts are becoming a focus of “hey, this might be the way to make people understand.” Theater, for example—even a collaboration [with] the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, [which had been planned for Campi Flegrei]. There was discussion of “what about immersive theater, poetry, painting, songs?” These are all ways of encapsulating recent events. I mean, looking at the past few decades and thinking toward how you [might] convey the potential for future risks, those are all things that are in development. All of this has really been put on pause by Covid, unfortunately. In effect, I’ve started writing with volcanologists—this I find really interesting—with volcanologists from Naples, who are usually spending time doing statistical analysis of scientific data from Vesuvius or Campi Flegrei. I’ve been co-authoring pieces on Covid, that they are doing statistical analysis on—because in both cases you’re dealing with low-frequency, high magnitude events—and thinking about future risks.

Campi Flegrei, 2004 [photo: Donar Reiskoffer; courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

WC: [That’s] one human creative response to a massive, catastrophic human disaster. What else is there that you can think of?

KH: The museum [in Chaitén] is not only meant to convey the scientific knowledge about the volcano that erupted. It’s meant as a commemoration for the people who lived through it. It’s also like going to Ground Zero—the World Trade Center. You can’t convey what it felt like in 2001 to somebody who was not there, so they’ve got that museum to try and interpret [the experience].

Art therapy was integral to the resettlement of Chaitén. There’s going to be another room at the museum for this art that was done between 2012 and 2015, art therapy to work people through the disjunctive feeling of “I was living my normal life, and then this mountain that I didn’t even know was a volcano suddenly exploded and everything was destroyed.” This was not a normal earthquake they were feeling. What was that sound? What was that smell?

WC: What was that smell?

KH: Sulphur is released. And the rumblings, if you’ve never been in an earthquake, there’s nothing more disconcerting, because you realize how small you are. It’s incredibly humbling because you forget.

WC: Do you think people [6,000 years ago] processed this information the same way we do? Were they thinking the same way that we think?

I think people have difficulty linking themselves to the inhabitants of the caves …. Did they process the same way that people in Chaitén are processing the volcano now?

KH: I think there’s something to the embodied experience, which is going to make the large-scale eruption of a volcano that you personally witness the same now as it was then. I think there is a dramatic realization of how much larger than us the planet is; about immense, unexpected risk suddenly being apparent.

WC: What about Laetoli? Tanzania, where footsteps in the mud preserved proof that our ancestors walked upright 3.7 million years ago. Even those individuals, who were australopithecines, do you think they suffered the same trauma and created the [same] metaphors for their experience?

KH: I think they remembered that volcanic eruption for the rest of their lives.

WC: Do you think they communicated to their descendants? Do you think they communicated “stay away from that hill,” or “that hill is special, go look at it, but not when it’s rumbling?”

KH: I have absolutely no problem with that concept. Yes, I think [they would] remember.

Animals remember the place where something traumatic or dramatic occurred and avoid it in the future. Take the simple example of a domestic dog. As a puppy, your dog is attacked by a Siberian Husky. For the rest of its 14 or 15 years, it’s not going to want to be on the same side of the street [as] a Siberian Husky. There’s a memory that we have that gets ingrained. I want to stay away from a risky location, or a risky creature. I want to be risk averse. I don’t have any problem with stating that prehistoric people would have [had] a memory of that event. They would clock it as having been incredibly important and impactive, and they would try to convey that, because that’s how you work through things, right? People in Chaitén, when they’re working through things—[using] art therapy—they’re trying to work through what happened and also “how do I process this?”

Art therapy in Chaitén [courtesy of Karen Holmberg]

WC: I’m curious about the way that they processed the world around them. Does that come through in your excavations? Do you find that the vulva is carved on the wall because it’s such a concern about childbirth, and death, and miscarriage? Is the art therapeutic in this way? Is it protective?

KH: I would veer more toward apotropaism—protective—rather than record. But I don’t know. Nobody knows. But also, how we interpret the past really says a lot about us, and we can only see it through our lens, right? So, what you’re trying to get at is really something I don’t think you can get at, and yet it’s so evocative to try and think about it. What was it like to see through their eyes? What was it like to see through their eyes and process with their brain? We don’t know, but how cool? And how cool that we can sit here and try and think that through as well. That’s kind of an amazing thing to do. But I think it’s very telling, too. The dysfunction and inability to communicate with what we are witnessing now, particularly in the United States, where a large percentage of the population believes the Covid virus is a hoax—it doesn’t bode well.

The fact that people did not come together; [the] fact that people were stockpiling and hoarding; the fact that people will not be swayed by data in terms of mitigating risk, whether you’re talking about mask-wearing or large gatherings, points in some worrying directions in terms of climate change and what’s going to happen.

We are completely aware of what’s going to happen in New York City in terms of sea-level rise within only a few decades. It’s not some kind of deep future of “ok, we know the big one’s going to hit California, and we know a big chunk of California may just slide into the sea, but it may not happen in our lifetime.” That’s sort of one thing you can put off. We know what’s going to happen within a hundred years. Before we are old people, we are not going to see a large chunk of what we consider to be Manhattan now, because it will be drowned, it will be underwater. Why are we going about our daily life in an unchanged way and not thinking about that? Why are we not being more proactive? We seem to respond to things after the fact no matter how much information we have. So how do we convey information differently, or better?

I think that in part there might be defense mechanisms that come into play. If you absorb and understand all the risks that are constantly surrounding us, you might just shut down; it’s overwhelming. But I also think that psychologically we are just not wired for anything that is low frequency and high magnitude.

WC: We’ve talked a lot about different ways to interpret data, and what outcomes [those interpretations] can lead to. I wanted to end on another volcano-themed site: Laetoli, What has that earliest human interaction with a volcano represented to you?

KH: For me, as an archaeologist, it’s the site that’s always been deeply ingrained in my brain. You know, Mary Leakey was exceptionally famous. She found these footprints in 1976 and it became a really big deal in archaeology. For me, it’s iconic in the sense that it indicates this very—like Pompeii—“lived” human experience with a volcanic event. That fact that you’ve got this multi-species thing going on, with all these animals running along, is really remarkable as well. That materialization of a past event that was fleeting and ephemeral and yet has this record that you can look back at. … There are so many different artistic representations—of what [the event] must have looked like, or felt like, for the people [who] were there—that are completely fanciful. We don’t know how much body hair they had or what color their skin was, tthe shape of their face—outside of very broad strokes—and yet you find so many disparate interpretations of that event, artistically.

Laetoli footprints replica, 2013 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

WC: This is the whole idea of art interpreting archaeology. What do you do about an enigmatic pair of footprints in the mud from two million years ago?

KH: I think you just have to be very transparent about the projections that you’re layering on. I think that it’s completely fair game to artistic interpretation, or re-creation, or representation, but you need to be very clear when doing so that you are creating a fantasy, an idea, and that doesn’t mean that it indicates the truth of that past. I don’t know if you’ve seen this new article [“Footprints Mark a Toddler’s Perilous Prehistoric Journey”] that came out on October 23 [2020] about prehistoric footprints: There was a young adult carrying a small child across mud, [periodically putting the child down] …. This is in the US Southwest. And in the returning set of footprints, the child is no longer being held …. How do we know what happened to that child? Where was that child taken?

WC: Couldn’t they just [have been] dropped off at their grandparents? Does it have to be scary?

KH: We don’t know. What I can tell you with full certainty is that both that child and that caregiver are now dead. But that’s uncanny too, to have footprints that show us exactly where somebody walked thousands of years ago, to know they were carrying a child as they were walking. It’s not something we’re supposed to have access to. The past is supposed to be in the past and gone, and yet the past is never gone, necessarily. It’s interesting to think of what artistic representations will be created from this set of footprints. How will they be different from [those that have been made] for Laetoli? If you had been given this assignment as an artist or an illustrator in the 1970s, you would have had a very different mindset than you’re going to have in 2020. What’s somebody in 2022 going to do when they get this assignment? There’s the very famous and accurate phrase, the past is a foreign country. It’s [the title of a book by] David Lowenthal. But trying to think of the mindset of a colonial American is sort of out of our reach. Even dealing with the mindset of an antebellum American is going to be very difficult for us to access. These were very different lives and very different lived experiences. So, you’ve got these physical and biophysical common bodies and geographic commonalities, and that does not mean there’s actual communication between the way that [they thought] and the way that we would process things and think, necessarily.

WC: What you said, “meaning is not conveyed,” is a very dark, but very true, precept to live by.

KH: We’re all perfectly aware that meaning is very difficult, even interpersonal, [between you and] somebody in your same time period and in your same household. It’s very difficult to communicate to another human being.

Will Corwin is a sculptor and journalist from New York. He has exhibited at The Clocktower, LaMama and Geary galleries in New York, as well as galleries in London, Hamburg, Beijing and Taipei. He has written regularly for Artpapers, The Brooklyn Rail, Bomb, Artcritical and Canvas and formerly for Frieze.