Julie Mehretu: Emergent Propositions & Entropic Systems

Julie Mehretu, “Retopistics: A Renegade Excavation,” 2001, ink and acrylic on canvas, 101 1/2 × 208 1/2 inches [photo: Edward C. Robison III; courtesy of the artist]

Share:

Standing before one of Julie Mehretu’s monumental paintings often reminds me of gazing across an expanse—perhaps overlooking the skyline of a city or seeing a mountain range from one of its peaks. The overwhelming desire to take a photo—to try to capture the view—is immediately thwarted by a certainty that the photo would fail to capture that very expansiveness in all its minute detail. The act of looking on such a grand scale, combined with the embodied knowledge of how a place feels to witness, creates a sensation of awe, of confronting the uncapturable captured within immensity. Such sensations are given form and content in Mehretu’s paintings.

Her deeply experiential abstract works are amalgamations of fragmentary images, marks, shapes and colors that reference cartography; architectural drawings and schematics; photographic documentation of current events and social uprisings; and more, mobilizing a vast lexicon of visual references. Mehretu’s midcareer retrospective had its debut at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and it is currently on view at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta through January 31, 2021. We met over Zoom while the exhibition was in transit between the two institutions.

Julie Mehretu, “Stadia II,” 2004, ink and acrylic on canvas, 108 × 144 inches [courtesy of the Carnegie Museum of Art]

Sarah Higgins: We’re talking on the occasion of your midcareer retrospective, exhibitions that are often discussed as an opportunity to look back, to contextualize, to do some stock-taking of your practice up to this point. They also seem inherently to create a bookend—the closing of a chapter and, thereby, whether intentionally or not, the opening of a new one. You have an opportunity to participate in your own historicization, but the process has landed in this very tumultuous and unprecedented year. I’m curious—given the need to bookend, to also look forward, to mark a turning point—if what has transpired in 2020 as backdrop to this retrospective has changed how you’re thinking about it. I mean, you work on these kinds of exhibitions for years, but you couldn’t have anticipated 2020 would be what it is. Has that shift in milieu altered the way you think about it as a bookend?

Julie Mehretu: It’s interesting that you bring up the idea of the survey as a bookend. We were working on the exhibition for five years. I hadn’t spent that type of time, going back through the work, that I did preparing for this show. In a way you become a student of yourself, while in the process of working on new work. One of the intentions of the exhibition was always to save space for really recent paintings. The last room has paintings that were made in the year prior to this exhibition. When the show opened in Los Angeles, it had three brand new paintings that were shown for the first time. That is not a body of work that is a closed cycle—if you will—it was an exploration that emerged after I finished the paintings at SFMOMA, the HOWL paintings—HOWL, eon (I, II). The HOWL paintings were finished [within a] year of the [2016] election and begun at the beginning of that election. The content of those paintings is so interesting to look back at now, [because] we’ve been protesting since the beginning of the Trump administration.

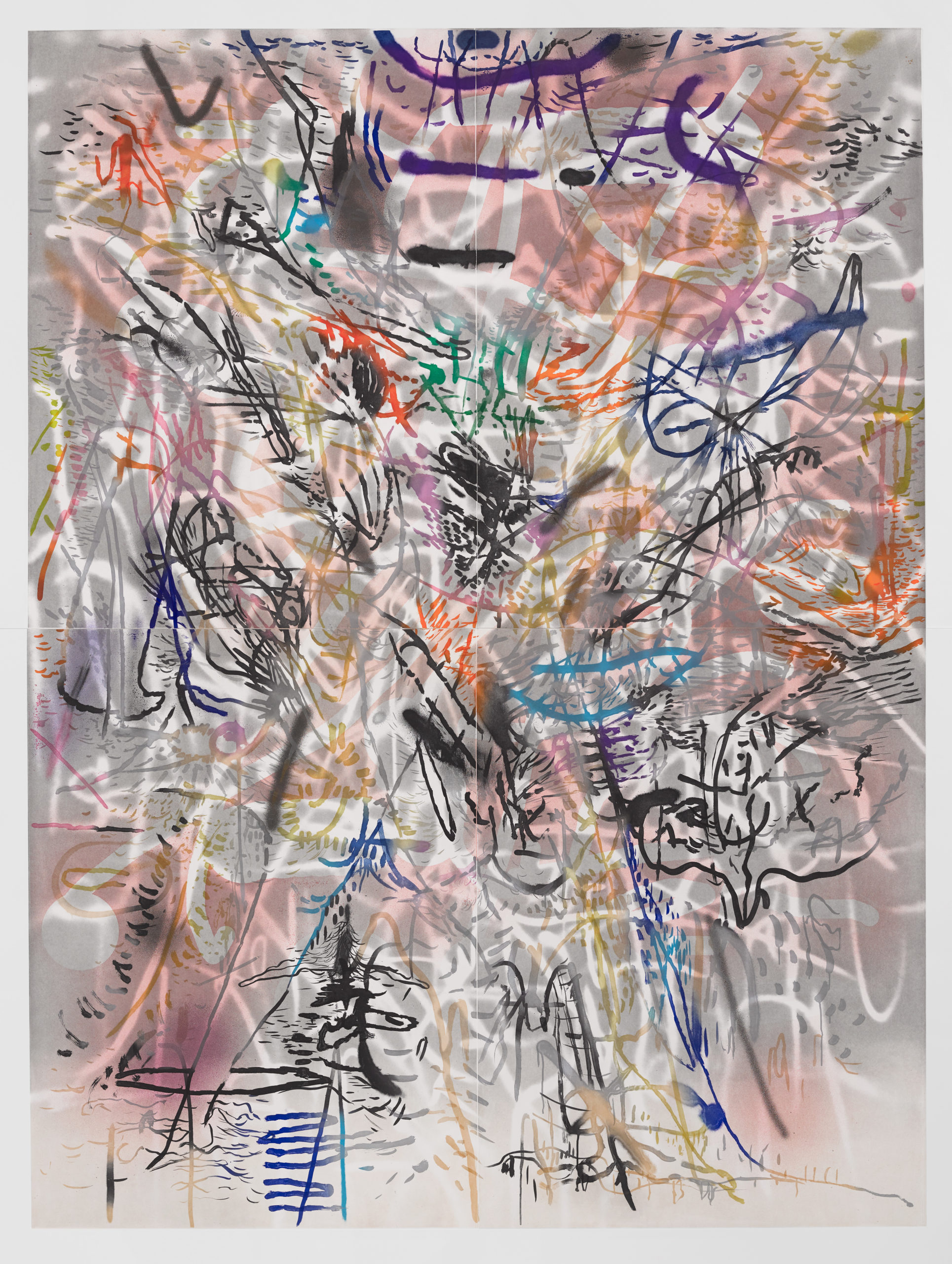

Some of these [recent] paintings in the exhibition have underpaintings based on blurred photographs of particular events, and one is based [on protests against] the Muslim ban that erupted en masse right after the president announced it. It was an instantaneous eruption of protest and activism that took place all over the country, [in an] effort to resist that fascist gesture, which was undemocratic in a very clear way. And then there was a similar eruption with the Women’s March shortly after that. That was enormous. And then [there is] another intention, or subject matter, in a group of these paintings with the rally [of] the right in Charlottesville. And this past summer, during the pandemic and after the killing of George Floyd, you had an intense eruption of protest and uprising. I’m about to open a new exhibition of paintings at Marian Goodman Gallery, where I’m continuing that cycle of work. So it’s almost as if that body of work is a bridge [from the retrospective exhibition] into this newest work. I think a lot of the work from the earliest moments has been very much about investigating power structures and individual agency, collective agency and possibility within it.

Julie Mehretu, “Epigraph, Damascus,” 2016, photogravure, sugar lift, aquatint, spit bite aquatint, open bite, 8.1 × 18.8 feet [photo courtesy of Museum Associates / LACMA]

SH: Your work is engaged with space and site, in content, but also in the way you reference cartography, architecture, and sites of historic events, sites of uprising, sites of change, of resistance. I’m curious if the most recent work, in the final room, becomes a site where you can respond to those changes of site, because it’s part of something that’s still happening, still fluid. Do the newer works change with each iteration as the exhibition travels?

JM: Well, several things: It was with intention to choose Atlanta, because of the demographics of the city, and Minneapolis; both institutions wanted the show and have been supporters of the work. These are really interesting and important audiences to me, personally.

I think that the work—the way that I’ve been thinking of the work of the last 10 years—is to try and negotiate a way of radical imagining. How do you pull from Black radical tradition? How do you pull from other radical traditions? It’s a question about how to invent and build, to find forms of liberation inside of being, inside of making, inside of creating, inside of inventing possibilities. That’s part of the insistence in these last paintings. I’m trying to invent this other space, another context from within the images, and to find fissures or find the ghosts—to deal with the horror that these images conjure—but also to ask, how does something else come through? That [barbarity] comes from a long history of intentional oppression and extinguishing of particular peoples, particular ways of being. Despite that, there’s been constant invention—of language, of sound, of possibility—and that invention is part of what I’ve been trying to push for in the work.

I’m really trying to work with the museum on how to engage a different audience, and how to bring various audiences in who are [also] thinking and inventing in these ways. And if we’re in the midst of a reconstruction right now—if we’re thinking of this time as an uprising and reconstruction—then what radical traditions are we thinking through? How do we think and create radically? How do we invent? These are core questions that I’m thinking about in my work. I think of the show and the programming we can do at the museum as a cross-platform place, a place of learning, and a place of collectively trying to—within different forms—push this agenda forward. Painting is one area where I find that I can look for liberation, within the [medium] and for myself. I hope that these time-based experiences in painting offer a place of communal conversation, investigation, or interrogation.

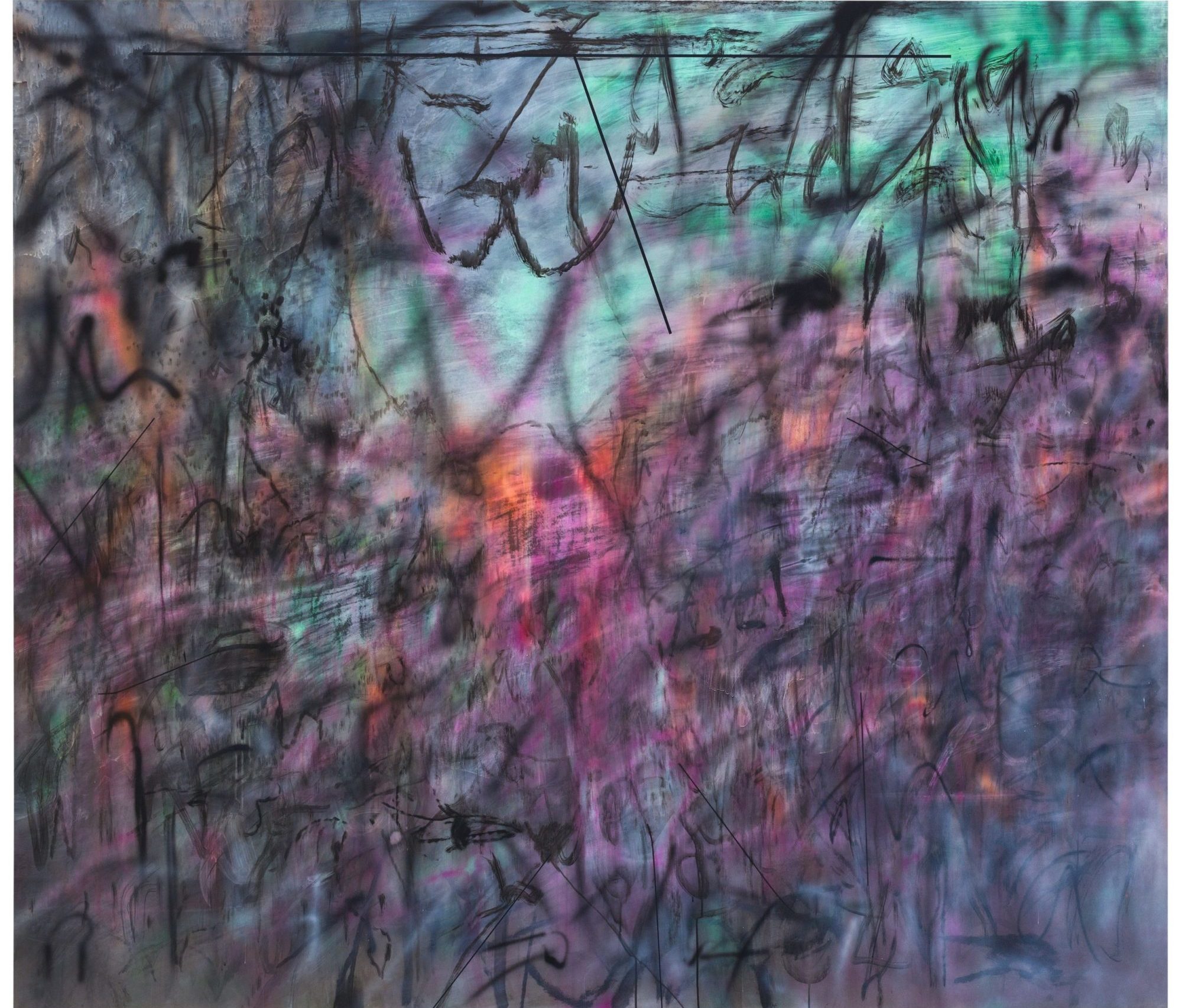

Julie Mehretu, “Haka (and Riot),” 2019, ink and acrylic on canvas, 144 × 180 inches [photo: Tom Powel; courtesy of the artist]

SH: I have a question, or a curiosity about how you invent and build. In the atomization of images, of a group of references, you’re also refusing the legibility of coalescence. There is clearly deconstruction happening in the work, but there’s also a kind of unknowability that touches on the expansiveness of the present. Do you think about the work as moving beyond deconstruction and into a space of proposition—proposing a future, of where we’re going? What does reconstruction look like to you? Or maybe “look like” is ultimately the wrong configuration. [laughs]

JM: Yeah, or what does decolonization look like? Reconstruction is work that’s never complete. It’s a project that wasn’t resolved and hasn’t been resolved in this country, and it’s hard to even understand how that can be resolved when we’re dealing with the bigger aspect of colonialism. And we haven’t really come up with a decolonial project in this country, or even a project of understanding ourselves. All of the work over the last 25 years has been about trying to locate myself within that intense web. What you said about the deconstruction that happens, it’s about taking all of these things apart and trying to layer them together, to collapse space and time.

I think there is a world-building that exists in these paintings, but it’s an entropic system. I don’t think there are propositions in them, other than conjuring of possibilities. And I don’t mean to be opaque in answering that, but there’s an open-endedness, more like presenting an experience, a spectral experience, a time-based, transformative experience. But I don’t know that it offers any kind of proposition or solution outside of what it can do, individually, to someone and their experience with the artwork and a belief that the experience is valuable.

SH: I’m into the idea of accepting entropy as a necessary part of any future. Utopian futures are often so simplistic, so reductive, or selective about what aspects of the world we bring into them. But that’s not how the world works—there’s overwhelm, there’s too much, there will continue to be too much, right?

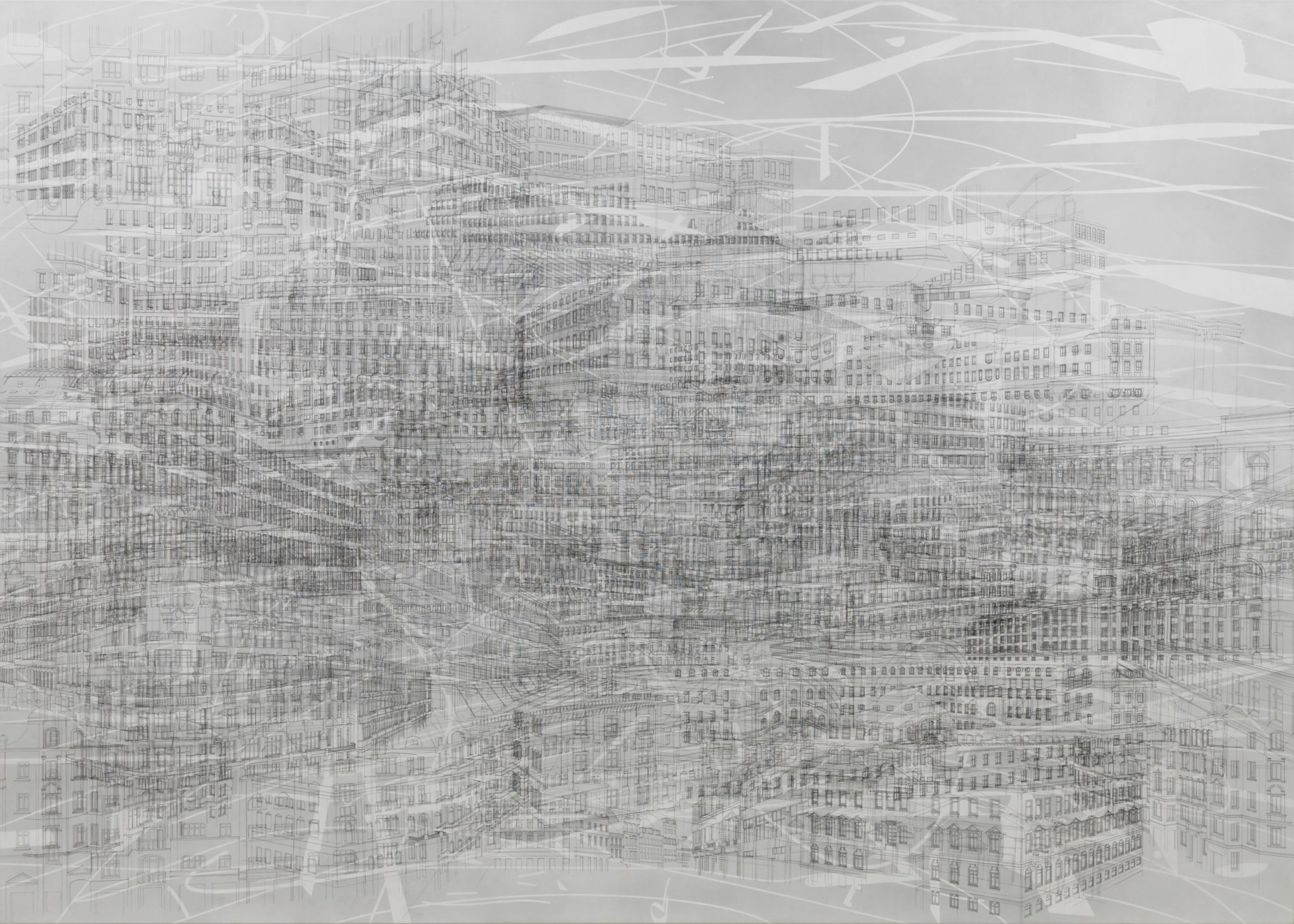

JM: But I like the idea of playing with feelings of futurity or feelings of those possibilities. So that’s why I use the word possibility. It seems so open but it’s actually interrogating historic utopian propositions. That’s part of the gesture of what’s ultimately embedded, metaphorically, in the architecture, and in those forms of construction and representation in the world.

SH: This is also where my mind is right now, because ART PAPERS’ next theme is about monuments and alternatives to monuments. I’m thinking about the act of removal, the act of destruction, of tearing down, as being liberatory, as clearing away something that was blocking our lived symbolic realities and space, from being able to emerge into something decolonial, something that looks like a future with a more multiplicitous notion of public that informs it. But then, the question becomes—well, what in their place? But why do we presume a replacement is needed? Why must something destroyed be replaced with something else to fill that hole? These are questions that are kind of swimming in the back of my mind.

JM: Well, in that sense I do think of the paintings as emergent propositions. If there is any form of proposition, it is about that insistence on deconstruction, through atomization, unknowability, through this form of recoalescing and bringing marks together. There are so many ways to imagine what could happen with that space, or with those voids, and I think all of that is part of letting go of certain desires, letting go of certain necessities. I think that artists and creative people are the ones who can interrogate and invent propositions, and each instance can be dealt with differently.

Julie Mehretu, “Conjured Parts (eye), Ferguson,” 2016, ink and acrylic on canvas, 84 × 96 inches [photo: Cathy Carver; courtesy of the artist and The Broad Art Foundation, Los Angeles, California]

Julie Mehretu, “Berliner Plätze,” 2009, ink and acrylic on canvas, 119 1/8 × 167 1⁄4 inches [photo: Kristopher McKay, for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation; courtesy of the artist]

JM (cont.): The idea that there could be some kind of larger proper response is almost problematic, because there are those who don’t even care about the monuments. The more important work in their mind is the constant pervasive racism and injustice that exists. The real work [in their mind] is about trying to build another place of liberation. I do think it’s an important place to interrogate—but I think that the open-ended possibilities, and the numerous contradictory possibilities, are interesting, and that’s part of the entropic reality that exists. We have to embrace the contradictions and go right into them and not be fearful of the contradictions that exist within.

SH: Yeah, and to refuse the totalizing force of a single answer.

JM: Absolutely.

SH: There’s something productive about resisting the urge to arrive at a conclusion, staying instead in a space of indeterminacy, a space of possibilities. Many possibilities are maybe more the answer than a single answer.

JM: That liminal place of those possibilities, of many answers, is the most potent place in a way.

SH: In your most recent work, the surfaces are becoming less sharp. There’s a blurred softness, whereas past work often had incredibly fine detailed lines. These surfaces seem to remove traces of the hand, of the mark-making, such that the marks exist in suspension. There’s not just abstraction on the largest scale but abstraction even at the level of the mark. What is the relationship between those formal gestures and the content or source materials that you’re using?

Julie Mehretu, “Six Bardos: Transmigration,” 2018, 31-color, 2-panel aquatint, 98 ×74 inches [photo: © White Cube, Ollie Hammick; courtesy of Gemini G.E.L., LLC. © Julie Mehretu]

JM: The materiality of the work comes from the history of the making of the work. The mark was always essential to that. The [earlier] surfaces were developed to be able to hold and not ever lose the mark, so that if you erase the mark you always have the palimpsest or the trace of the mark there. I was working very early on with very fine, thin radiograph marks—architectural—that come out of the history and traditions of mapmaking, charting, and analyzing. I then moved into this place where the more I continued to work with the marks, the more the marks in themselves became primary, became the activist gesture if you will. I became most interested in those insistent gestures, and how they could evolve. The marks became much larger, they became more gestural, they merged with other histories of mark making. I think that’s why I refer to them as neologisms—visual neologisms—like a Philip Guston kind of gesture that morphs into a Hammons handprint. These things come together and evolve very differently. A particular kind of caricature might be reminiscent of a Kara Walker gesture, but then it moves into something else that feels almost like something from the renaissance.

There is a lot of erasure now, there’s a lot of drawing and sanding, and so the surface has been developed in a way that can withstand that. I can fully sand something out and still keep part of the surface, or the sanding and erasure becomes part of the surface, and becomes part of that visual action, and part of the way that the image evolves.

In the last four years I have been working with using blurred photographs as the source for the underpaintings. One piece in the exhibition is based on architectural renderings of Damascus, and erased parts of Damascus, [referencing] erasure happening there throughout the Syrian Civil War, and the cost of that [destruction]. Looking at images projected onto the paintings, when they were out of focus, [I saw] this apparition of place. It was almost like all that was embedded in that photograph was there, without the photographic detail. As someone who’s also interested in how to unlearn certain decolonial gestures of photography, I became super interested in these particular photographs that resonate culturally. They’re mediated images that we consume at a rapid pace …. Certain images rise to a different level in our collective consciousness to encapsulate a moment, but there’s usually some weird dynamic as to why these [particular] images [do so].

JM (cont.): I became interested in photographs that felt like they really captured a certain tenor of a particular thing. [All] of them were really intense photos; one of the Charlottesville conflict made me think of history paintings by David and Delacroix, such as Liberty Leading the People or David’s The Intervention of the Sabine Women. They are paintings where the blurred photograph carries in the color and light and construction of the space, or of the action that’s happening in that space. The gesture of that space is clear. It guides the whole painting, it is the DNA of the painting, but it is also the space, color, and light that it’s being painted within, the tenor of it. My engagement is to invent something else within that space. Like the painting Hineni, which is in the exhibition: It was based on one of the northern California fires [in 2017]. There’s no doubt that it’s a fire, even though it’s just blurred oranges, pinks and yellows—a kind of experiential feeling of incineration that’s imbedded materially. When I was much younger, each material step was really important to the concept of the work. I feel like the work has really evolved from its early materiality, through a different way of working, to where the surface—what you see—feels almost reflective and somewhat immersive, a kind of liminal space by itself, and that liminality is the place of emergence.

Julie Mehretu, “Hineni (E. 3:4),” 2018, ink and acrylic on canvas, 96 × 120 inches [photo: Tom Powel Imaging; courtesy of the artist]

SH: There was a very 20th-century notion, I think, that the photographic image could convey truth, or could make a kind of concrete evidentiary claim. And we now know—in our super image-saturated time—that yes, images have a powerful ability to serve as evidence, but that a truth claim is actually subject to power structures outside of and beyond the logic of the image. Structural racism will fight against the image to lay a claim over the truth, geopolitics will fight for the power over that claim. The image can assert truth, but it can also be silenced or rendered completely irrelevant. What’s left then? What is that image now? A painting that doesn’t show a fire but is immediately experienceable as a fire has a different kind of truth claim than the representational image. I’m curious how you see your work participating in that push and pull between the representational image’s ability to do all that we had once, perhaps, hoped that it could do, and its inability to do so.

JM: I’m hesitant to even think of truth claims outside of my own experience. I think for me it would probably be about my experience as a consumer of this media, bearing witness and working from within that space. I do think that there’s a lot of complexity to what you just described. We just had the first presidential debate [last night], and anyone who witnessed it, and then read the news and media responses to that [today], it’s like they were talking about two different realities. That’s what’s so fascinating: how media is being consumed, repurposed, regurgitated, how it’s being digested, and co-opted. We’re in a time when the totality of that process is ungraspable; it’s like a hall of mirrors where you can’t locate yourself, or even necessarily understand time, reality, and what is being constructed. There’s a constant pseudo-alterity morphing and shifting to create to really scary possibilities, and I think that one of my efforts is to try and find myself in that. That’s one of the reasons I’m interested in looking at the blur.

One of the reasons I became so committed to making art is I remember being moved, extremely moved, by works of art. Even representations of mass systems of power and oppression can be incredibly moving. The power of that experience is what I’m engaged in, what I want to be in. That’s what I’m more interested in. Part of that is you’re bearing witness to something and you’re trying to negotiate how we try to make sense of the sublime, and the sublime being the actual terror of the reality of our existence.

***

Julie Mehretu’s solo exhibition about the space of half an hour at Marian Goodman Gallery in New York opened November 2, 2020 and is on view through December 23.

Sarah Higgins is editor + artistic director of Art Papers.