Joyce Pensato

Share:

This interview first appeared in ART PAPERS September/October 2014.

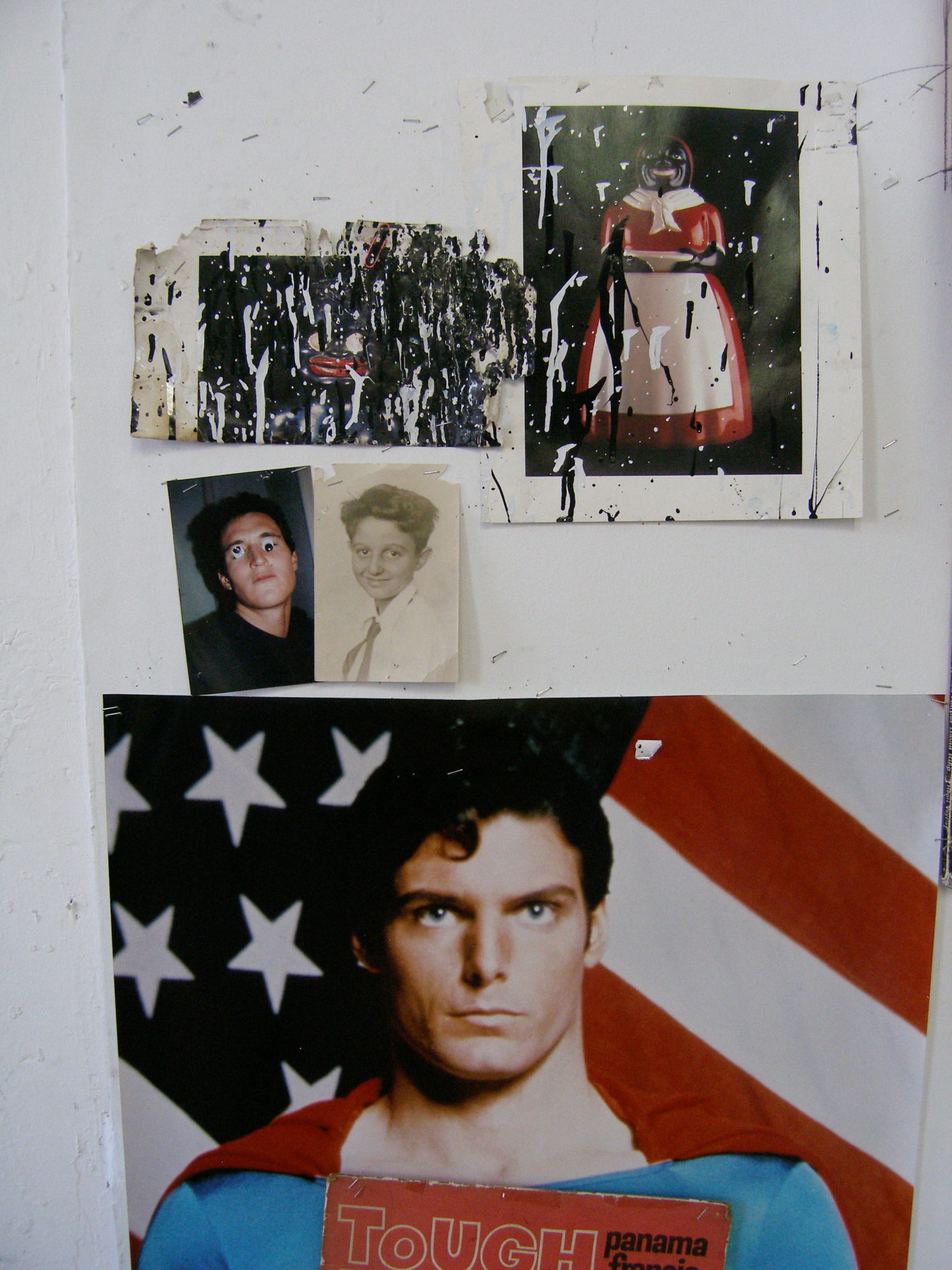

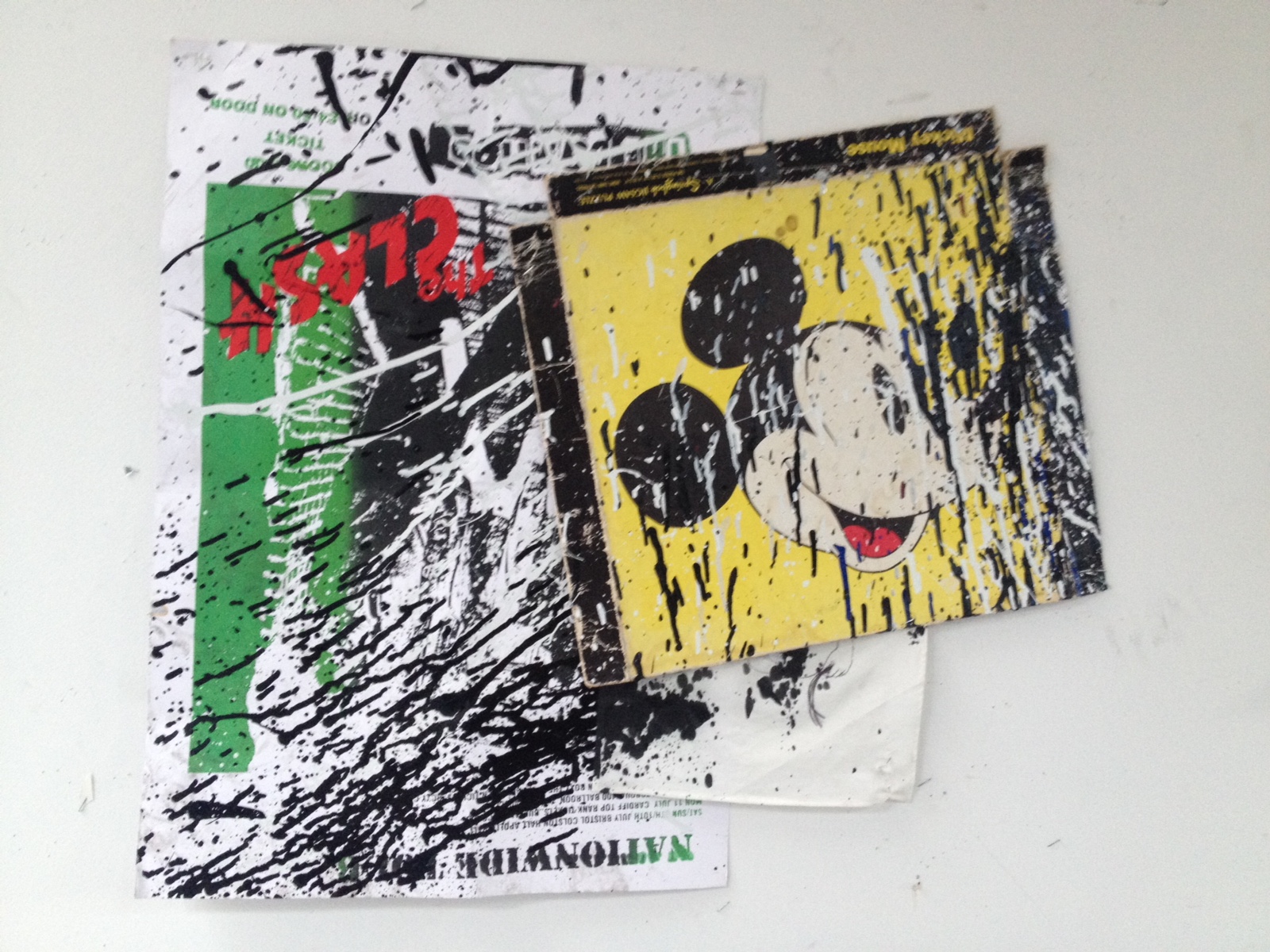

When Joyce Pensato turned up at the Clocktower recording studio back in 2011 to do an interview as part of an oral history of the Williamsburg art scene in the 1990s, it was because Mike Ballou, Ward Shelley, and a few of the other Brooklyn mainstays had insisted that any record absolutely had to have her testimony. Pensato, on the other hand, was pretty clear that she hadn’t been part of it. She is from Brooklyn, and she sort of is Brooklyn—like its residents, she either gives you a very straight answer or speaks in riddles—but she also claims to hate it. In her Williamsburg studio, she engages the darkest sides of cultural signifiers such as Homer Simpson, Eric Cartman, Mickey Mouse, Daisy Duck, and Batman, lending them the authority of saints—though she doesn’t watch cartoons, and they mean very little to her on a narrative basis. Instead these characters mingle with glossy movie stills, headshots, promotional cardboard cutouts, and talking Muppets; a squad of giggling Elmo dolls patrols the premises, and still more grungy toys line the shelves. Everything is spattered in hi-gloss enamel paint, which by its apparent wetness only increases the spontaneity of the mess. Here is culture soup, its ingredients rotated in and out of proximity to the viewer and the artist: inverted, negated, or worshipped, they are always familiar. The ensemble functions as a whole, but none of its parts really “work” together. Barely noticeable is a hotplate in the corner by the window, and on it, a frying pan holding a gallon container of Joyce’s highly flammable enamel paint of choice, bubbling merrily. WTF.

Will Corwin: Is the studio “Joyceland,” or is Brooklyn “Joyceland”?

Joyce Pensato: This is no land, this is just a studio! This is the place where the juices are floating, where you feel comfortable to be who you are, and if I just want to lie on the lounge chair for a month or two, I can do it. I’m surrounded by Charlie [Pensato’s English Spaniel], Batman, and all this stuff. It’s my world, my environment where I work. My world would be walking to the Laundromat, the park, like, right around here—so the studio expanded to this community. Does that make sense? My world.

WC: Is there something miraculous on the way to the Laundromat?

JP: Well, you meditate and space out. It’s very familiar—you could probably walk there with your eyes closed, and that’s part of my environment. If I go to the city, I’m taking a break from my inner space, but if you’re going to the Laundromat you can still be in your own world and thinking about your paintings and stuff like that.

WC: What do you think of Brooklyn these days?

JP: I now like it. Before, I hated being here. Who wanted to be stuck in Brooklyn? When I was younger, where I lived in Bushwick was very provincial—it was like a small town. And then everybody came to me, for God’s sake! Now they want to throw me out, or they did want to throw me out.

WC: What do you like about it now?

JP: It’s a community, it’s familiar, it’s like a small town—all the things I hated!

WC: Do you think you were part of the “Brooklyn art scene”?

JP: No. Only when I got back from Paris in 2000/2001 did I become part of it—I was a big snob before that.

WC: What scene were you part of?

JP: Nothing. That’s why my career was nowhere. I looked always to New York and I pooh-poohed Brooklyn. Until 2001, when I was desperate!

WC: Why do you have the toys everywhere? They kind of watch ….

JP: Oh, I never think of them watching me. They have eyes and they’re all looking—I mean, right now they are looking at me and the painting—but they can look the other way or at the floor. They hang out.

WC: How do they go from being a brand new clean Elmo to being covered with paint?

JP: Well, I don’t “paint” Elmo. The Elmos are just hanging around by the paint and brushes. I know if it feels [like] too much, then I bring some other Elmos in. It’s just part of the feeling of what I want in the studio. I’m not working from them. They kind of make me laugh. I think it’s really funny that they’re all covered with paint and then they start talking.

WC: When did you start using the distinctive enamel paint that’s all over them?

JP: Back around 1990, a major thing happened in my life: I accepted myself. I was doing these fantastic cartoon drawings, and then I was doing totally abstract paintings. I’d be in different shows for each one—it was like two different people. The abstract paintings looked like everybody else’s. I was supposed to have a show with them and it got canceled. It shocked me, and I started to look at what I was doing. I said, “Why am I trying to force these abstract paintings? Why not embrace who I am, what I love to do?”

So I thought, “Who is the hippest guy that I know who’s doing something with not-normal paint?” It was Christopher Wool; I asked him what kind of paint he was using, and he told me. I played with it, and I found a way to open a whole new world for me. I found my language and tools. I couldn’t screw it up: I didn’t know how it worked, but I knew it dried quickly. I liked the feeling that you just did

WC: What do you feel about other artists using cartoons or a cartoonish metaphor? Would you site yourself within that periphery, within that school?

JP: I’m a wannabe; I would love to be. I love, love Paul McCarthy. The first time I met Paul was way back in 1992—we were in a group show at Luhring Augustine. He had a box of dirty toys, and I said, “Did this guy go in my studio and take my toys?” I felt a connection to him immediately. Now he’s cleaned up his act. I’m totally a dirty artist.

WC: Well, he’s kind of doing porn now.

JP: Maybe there’s a future for me in porn! You’re never too old. I like in-your-face and grabbing onto it and holding it. My hands are all over the place.

WC: Do you position the toys?

JP: I put them there, but I’m not conscious of it. I’m conscious of it in a gallery show; I try to make it feel as natural as possible. But I don’t do it here in the studio. Elmo is Charlie’s favorite toy. If you start playing with it, he’ll come grab it.

WC: When did you first discover Elmo?

JP: A couple of years ago. You know the fish that talks or sings?

WC: You mean the Big Mouth Billy Bass?

JP: I thought, wouldn’t it look cool in some sort of set up? So I went into the Chelsea Goodwill store. There was a kid there who was about six years old, and we were both looking at Elmo, and I thought, wouldn’t he be funny? And his mom said to take it because she’d had it with the Elmos. Now I’m on eBay buying Elmos.

WC: Did the Ducks, the Mickeys, the Fozzie Bears used to hang out the same way Elmo does now?

JP: Oh, yeah! All who remember me in 1973/1974 remember the studio I had. It was full of any debris, ducks, mice—anything I found in the street I would bring up to the studio. It was packed. I had to look at something. It gives you inspiration.

WC: When did you start working with cartoons?

JP: When I started to work, officially, I was a student at the Studio School in 1976. We embraced Giacometti, Cezanne—the real traditional French guys—and we also embraced Hans Hofmann and Willem de Kooning. Mercedes Matter was the dean at that time. Everybody was working with still-life materials—apples and pears. It was a stale thing to me, so Mercedes said: “I don’t care what you work from, get something you want to look at.” At that time they had a life-size Batman cardboard cutout. When I first saw him, I fell in love with his ears. The bells rang, putting Batman in all different positions in the studio. It was a still-life format; then I started to invent my own space after the Studio School, more abstract.

WC: Do you like Batman as a “trope”—as in, the mythology?

JP: I couldn’t give a shit about that.

WC: Do you like that he has animal characteristics, as a hybrid being?

JP: It’s the aesthetic structure. Superman is too human, Superman has a real face—I like disguises; I like masks. I tried doing Spider-man, but I found him too round and soft. … Batman is very angular—a tough guy—but he also represents pop culture. They have to have something deeper that I connect to. If I connect to it, I know the viewer is also connecting to something as well. I haven’t analyzed it too deeply, but I think I’m connecting to everyone’s inner self—to their childhood. I know I’m just having fun, but I’m dealing with the American icon. They have to be more than Mickey Mouse with a lobotomy. Icons! I like icons.

WC: What do you like about Mickey?

JP: It was the early 1980s—and again with the fucking ears. Also, his body is roundish—very abstract. I had a couple of Mickey’s hanging out—friends would give them to you, or you could find them in the gutter or the street. I would hunt them down. I like something that has a past, and what a mess they were! Their hair was coming out, they had had a hard time, but you feel a connection to some of them.

WC: How do you feel about “cuteness”?

JP: I don’t like cuteness. Cuteness is not there.

WC: And Cartman and Stan?

JP: They’re not cute; they’re bad boys. I use them as a form of getting into the paint. I see them as abstraction—they’re very simple and abstract, a couple of swipes with the brush—but they mean something. Homer is amazing. He’s a symbol of every man with a bald head. I don’t watch The Simpsons, but I love the way they’re drawn. They’re an American culture thing. I seem to connect with that. When I was living in France I tried to get hooked up to the stuff in France and Belgium. Tintin? I had no connection to it. I find I’m still crazed over Donald Duck.

WC: Is it something about anthropomorphization? Donald’s hat and tie ….

JP: He [is] also very expressive: he can look angry, he can look very vulnerable …. With Mickey, there’s nothing there but a high-pitched voice. I sometimes put Donald’s beak on Mickey—I start putting favorite parts of different people …. Of different “people”! Of different characters. To me they’re like portraits.

WC: When you do this pseudo-portrait, it’s you connecting with the “soul” of whatever entity it is?

JP: I hope that it has that.

WC: How do you position the installations in reference to the paintings?

JP: Same thing. My last show at Petzel [Batman Returns, 2012] was bringing my studio there. I see it visually as a beautiful set-up: the drippings on the floor, the cans, the empty cans, the paint. Then you add a couple of Elmos—it’s almost like you’re building a theater piece, a set, but it’s not going to work if it’s staged, it has to come from the heart.

WC: What’s the process for making a painting, beginning with the blank canvas?

JP: I have an idea of what size I want to do, it’s not totally “blank”—usually it kind of related to some paper size, something I do drawings on, that’s how it starts. I sit here for a while until I connect to what I’m painting. Like Homer: all of a sudden I could see that on the canvas. Then I just go ahead and do it.

WC: Do you sketch out the image or do you just start painting right off the bat?

JP: Sketch? What’s to sketch? We get the big fat Japanese brushes and splash on the paint. It’s drawing with the brush, like an ink drawing.

WC: How do you know when it’s done?

JP: When it feels like it has all the things in my head that I would want. At times it looks like I could stop and it would work, but inside of me I feel I have to work on it, keep working—I want to make it something else.

WC: Do you feel guilty if it happens too quickly?

JP: Yeah, I feel like I have to really push it. And sometimes I fuck up whatever it is.

WC: Are the portraits about recognizability?

JP: I like things really big, direct, in your face. I think it has a lot to do with when I started working in the big studio, seeing from far away. It’s almost like a billboard.

WC: That makes me think of your larger, ephemeral wall-based pieces. Do you like the idea that it won’t exist for long?

JP: I accept it. It’s almost like a performance piece to me. I did one in Santa Monica [Santa Monica Museum of Art, 2013] of Daisy Duck, and I felt the face was so expressive—it had the feeling of an Edvard Munch. I thought that was a masterpiece. But I knew going into it that it would eventually be gone.

WC: What is the appeal of working on this scale?

JP: The feeling is to have a big presence. Growing up Catholic has something to do with it. Going to church you’re seeing the altars, the theater. I went to church every Sunday, but I did a lot of fantasy dreaming there.

WC: What did you dream about?

JP: Hollywood, and it was not religious! I love all that heavy emotion, the drama of Christ on the cross. I couldn’t get enough of it. Even a big Donald Duck face is a symbol that we all know, but it’s also very powerful.

WC: Do you think your paintings are funny?

JP: I know I have a dark sense of humor. When I was a kid, polio was a major thing. The kids were going out like flies, and the news would run pictures of [someone] in an iron lung, smiling happily at a mirror. I mean, it wasn’t quite like that, but that’s the memory. It made me think, wow, that would really get a lot of attention—they were happy, they were laughing. My parents didn’t give me much attention, so I wanted to have polio, too. It’s like the Weegee photograph where somebody drowned and there’s this woman smiling at the camera.

WC: How did photographs start to come into the mix?

JP: I always love taking pictures. In my studio I’d have my collages and photos around, and as I worked, paint would be getting on it, and I loved it. They were just part of my studio [the paint-spattered images], and I would become aware of them when somebody visited. It was almost like a boxing ring, splashing paint as punching. Now, I’ll purposely get posters of De Niro in Raging Bull—there’s something beautiful, the emotion on his face.

WC: You’ve also got Muhammad Ali.

JP: He’s the new one, he needs to get something. [The paint] almost looks like blood, except it’s black and white, and the markings to me are quite beautiful. It’s like cooking: you don’t want to overcook it and ruin the whole fucking thing.

WC: You’ve got almost as many photographic, human icons, as you do cartoon ones: Robert De Niro, Muhammad Ali, Abraham Lincoln—

JP: —Gena Rowlands, who I think of as my “inner me.” I wannabe Gena Rowlands. I think of that image with her, with a gun, as a feminist image. A strong woman with a gun, pointing at the viewer—that’s how I see myself. Gena Rowlands with a gun and then De Niro, all bloody, they’re me, both of them. One is, “I’m going to keep going, no matter how much you punch me in the head,” and the other is like “All right, gotcha.”