Jessica Vaughn: In Polite English, One Disagrees By First Agreeing

Jessica Vaughn, Trays for Working, 2018, various repurposed lunch trays, dental trays, styrofoam trays, kidney trays, medical trays, plant trays, manicure trays, paper trays, coin trays, wood, lacquer paint and hardware [courtesy of the artist and Martos Gallery]

Share:

Magdalyn Asimakis: You’ve been working on a new project lately that expands your investigation into how material and physical structures can and do shape our reading of space and labor—and you do that through sculpture, video, and text. Though this is the first time you’re looking at corporate spaces in your work, it’s not the first time you’re examining institutional space and institutional infrastructure.

Jessica Vaughn: Right. My previous works brought together a series of objects procured from different manufacturing corporations that provide seating for the Chicago Transit Authority. After Willis (rubbed, used and moved) was made from used, stained, and worn seat inserts from the Chicago Transit Authority trains. Additionally, there were sculptures made from discarded, leftover upholstery and scraps from the manufacturers’ assembly lines. These works, named after the manufacturers’ color swatches, were arranged on the floor. This series focused on materials taken directly from the production of assembly—or the corporate setting—and from the infrastructure that they served: city infrastructure and public transit.

MA: In your new work, compliance comes up as something both physical and conceptual. The word compliance, in this context, originates in physics—this idea of a flexible material that supports production. So, when thinking about this characteristic in corporate or institutional spaces where, in this case, diversity training was required to comply with government standards for equal opportunity workplaces, it becomes a loaded term in that the businesses must comply, but the organizational hegemony is sometimes unaltered. So, I was wondering how you think about this incompatibility.

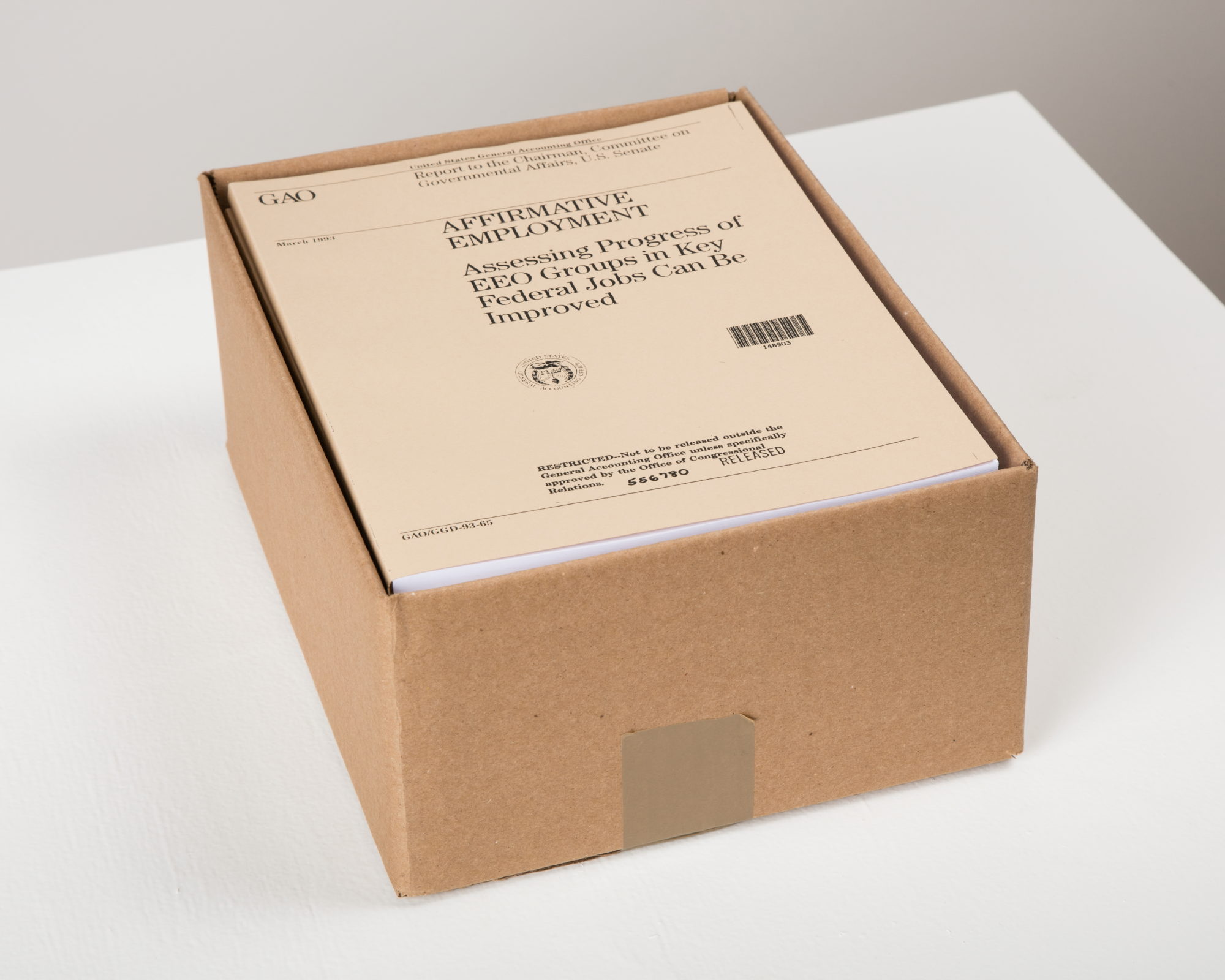

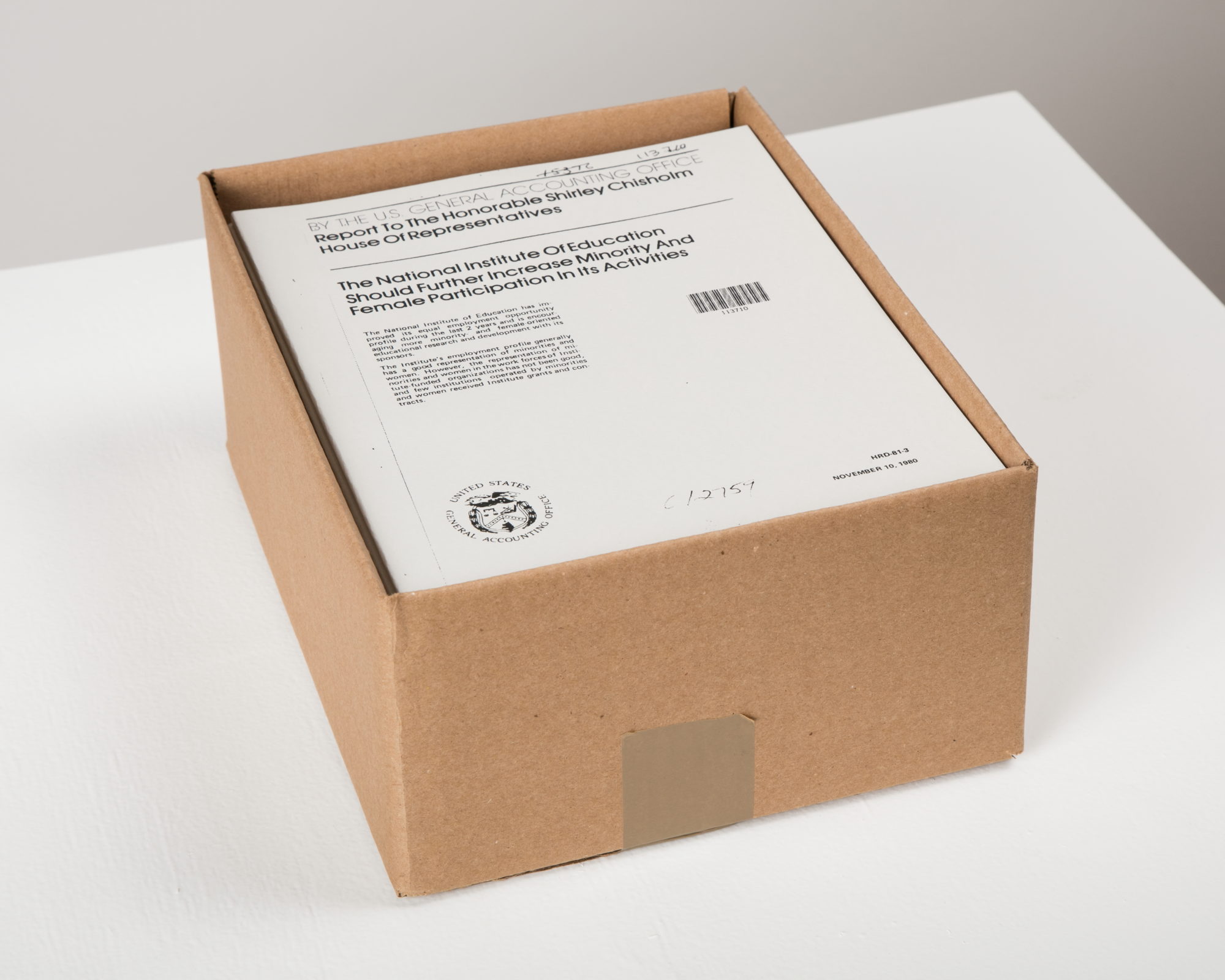

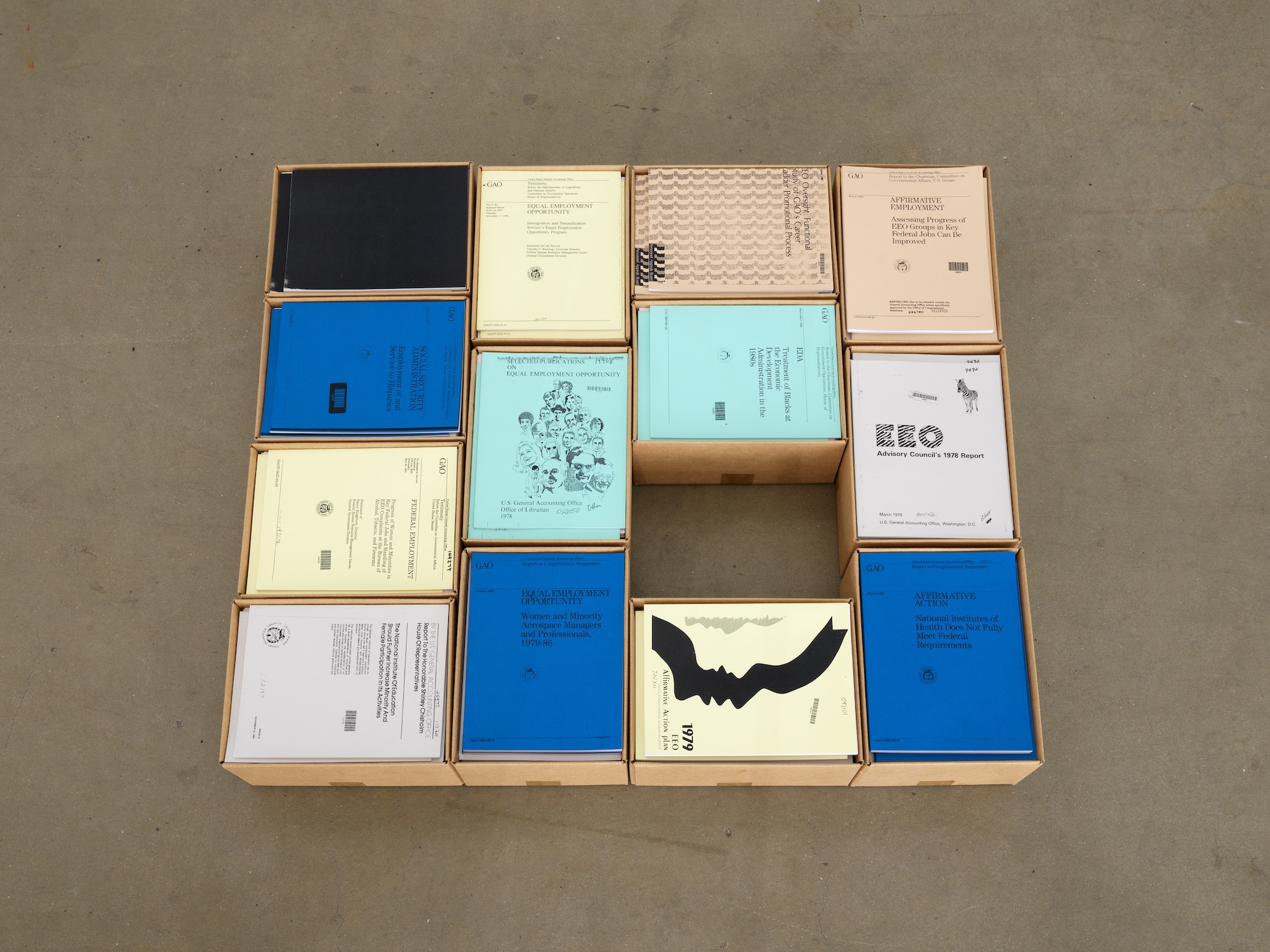

Jessica Vaughn, Blanks, 2018, 12 unique blank 8.5 x 11 inch books, paper, cardboard, tape, 38 x 36 inches [courtesy of the artist and Martos Gallery]

Jessica Vaughn, Blanks, 2018, 12 unique blank 8.5 x 11 inch books, paper, cardboard, tape, 38 x 36 inches [courtesy of the artist and Martos Gallery]

JV: Sure. I do see compliance operating as both a physical and conceptual term. With the train seats from my previous works, for example, international standardization dictated the particular measurements of the seats, along with smaller configurations of American standard organizations as well. The standards are based, for example, on the limits of machinery, typical body mass, safety measures, and economics. Also, written laws and policy figure as measures of compliance—executive orders, civil rights policy, the law in concrete ways, and sometimes in indirect ways—register compliance in spaces of labor and on their workers.

The beginnings of affirmative action in the United States, first implemented under the US federal government contracts in the 60s, were aimed at implementing equitable hiring of racial and ethnic minorities, given historical patterns of discrimination, specifically towards African Americans. When training under the guise of diversity management is, as you suggest, implemented to replace affirmative action or elements of equal employment opportunity measures—actual law—it obfuscates the original means of address. Diversity becomes a concern exclusively for soft policing or correction of isolated incidents—a hope, in a way, that the market will correct past grievances and discrimination, rather than the state. In this case, compliance removes difference, in an attempt to make the worker and goods accessible for production and consumption. In a sense, measures to address diversity become the invisible language of global bureaucratic and corporate structures.

MA: And, building on that, you and I speak a lot about diversity rhetoric and the use of optics and metrics to prove diversity in an organization, or more accurately to prove the compliance with diversity goals. Inclusion is vital, but due to the use of corporate processes in places such as art museums, the success of diversity initiatives is often measured by optics, namely strategically gathered metrics that translate well into board report lingo. And taking a historicist approach to this data can also give the impression that the progress is more comprehensive than it is in reality. So, we are essentially taking contemporary ideas and dropping them into archaic infrastructures.

JV: Yeah, I do think that there’s a way in which cultural institutions sometimes miss the mark on moving beyond treating their programming as advertisement or a product directed at specific viewer demographics. Especially when the actual structure of the institutions stay the same. For example, small, wealthy board memberships that dictate not only funding structures, but also—to a degree—curatorial framing based on trends in the art market. When these institutions rely specifically on data, metrics, and attendance numbers, it allows their programming and curatorial decisions to function without commentary or critique. It is kind of like, if the data says so, it must be right. When the primary concerns for an institution’s programming are based upon this matrix—a color-blind, one-size fits all approach, with the feeling of actually counting for everyone—the institution has, in practice, only accounted for those who chose to identify.

From my perspective as an artist, sometimes you work with curatorial departments that have little knowledge of work by artists of color. Not just [lacking knowledge of] the historical lineage, or contemporary cousins that influence the work, but [not] even having the language to be in conversation with an artist. When the language cannot be accounted for by the institution, you are left with museums and galleries exhibiting work by artists of color through the lens of either an intense pedagogical framework—as literal advertisements for their public programs—or through figurative representations mediated by the current political news cycle. This really leaves no room for critical interpretation that considers where the artist’s work sits in the world or the multitudes the work may derive from. We are not afforded that luxury unless the artworks can be explicitly read through the figure.

Magdalyn, as a curator, how do you make decisions about inclusion, and what does that mean to you?

Jessica Vaughn, Visible Hands (still), 2018, digital video, 3:48 minutes [courtesy of the artist and Martos Gallery]

MA: It’s something that I think about a lot, and not just in my practice but also in terms of infrastructural strategies like what you’re exploring in your work. I’m interested in what you said about the relationship between artists of color and curatorial and marketing departments. And my criticality around [diversity] metrics comes from my time working in institutional contexts where infrastructures can basically translate identifications into checked boxes, or where single individuals can become responsible for representing entire communities, and that’s a lot of weight, which is what you were saying, as well. Translation is so important in a calcified bureaucracy. There’s a desire for mastery, which museums strive for and is rooted in the colonial mindset. But it also becomes this kind of neoliberalization of inclusion, which is why I ask you about hegemony. I’m always curious about the tension between old structure and contemporary work, which you understand from a different perspective than me.

I try to ask how can you engage in praxis from beginning to end rather than just in representation. There’s no one answer, but for me it’s ongoing dialogues with artists, listening to what they’re trying to do, reading, and always thinking about intersectional anticapitalist ethics and approaches to process. These can be applied in any context, as a modest way of pressing back on a colonial and neoliberal arts infrastructure, instead of putting a lot of energy into making sure that practice translates to the way that we have all already been conditioned to see things.

JV: I like what you’re saying, especially when thinking about inclusion. I also think of inclusion as a process that is ongoing, that doesn’t rest, that isn’t stagnant. It’s about challenging representation and bringing individuals together to create a set of circumstances that will consider a diverse set of ideas and experiences for present and future projects. I think about how Andrea Fraser’s book 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics does just that. Her listing of funding to American art institutions not only shows the intersection of money and politics over time, but also in the present and future. It acts almost as a guidebook to how artists can call attention to those institutional practices that don’t serve the art, artist, or politics of equitable inclusion.

MA: It’s really incredible how Fraser reveals the underpinnings of why things are structured the way they are in museums, and really importantly how that converses with American politics. Part of your new work includes footage from 1990s and 2000s diversity training videos, with transcripts of the text superimposed. How do you see these older videos in relation to contemporary institutional approaches to diversity, and not necessarily just in corporate spaces but perhaps also academia or art museums?

Jessica Vaughn, Blanks, 2018, 12 unique blank 8.5 x 11 inch books, paper, cardboard, tape, 38 x 36 inches [courtesy of the artist and Martos Gallery]

JV: There’s still this flattening of differences that occur in institutional spaces. A sort of “color-blindness,” or lack of acknowledgement that problematic structures toward racial and ethnic equity exist because of historical patterns of racial discrimination in this country. I think that calls for racial and cultural equity have in more recent years come full circle to address concerns for civil rights gains from a moral perspective, but still, there is a tendency by many art institutions to address racial equity primarily and only out of market and economic concerns. Educational programming is seen as a conduit to bridge the market concerns of diversity within institutions.

The US federal government historically had a hand in bridging educational and economic institutions together. The GI Bill post-World War II was used as a means of preventing a slowdown of the economy. Government labor policy that directly bargained with unions in technical and trade schooling, specifically for the inclusion of black workers during the Second Great Migration and after the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, is another example of stabilizing civic economic concerns through job training and education. In my forthcoming work in video sculpture and installation, I see institutional diversity training as an extension of such education driven by market concerns.

The training videos of HR employees mediate the financial and legal concerns of management through best practices and education. And, in this case specifically, inclusion and diversity. An older work by Allan Sekula, School Is a Factory, is a great piece that directly extracts the relationship between schools and the economy. Not necessarily hitting on these ideas of diversity and racial inclusion, but still really pinpointing the link between schooling and economics.

MA: Your newer work uses materials and architecture found in different sites of labor. For example, cubicles, drop ceiling, and shelving. Can you speak to the spatial aspects of your new work’s installation?

JV: Sure. I wanted to consider different architecture components that make up contemporary office work environments. The sculptures use contemporary office components such as acoustic tiles and fluorescent lights to create a drop ceiling and cubicle walls that make segregated workspaces. With this work, I wanted to consider the space of the floor and the dead space of the ceiling. The use of a drop ceiling is an extension of a grid, just one that happens to be turned upwards. I wanted to mess with the logic of the grid and the structures imposed both by architects and city planners, to the extension of a city plan used by urban developers who divide neighborhoods targeted for economic development—or not—with mapped-out and gridded spaces.

The materials I choose to work with fit the realm of modular architecture, something that is flexible and typical, architecture that corrects itself for the market. I have been looking at architecture that encompasses the large open floor plans built and aestheticized through typical plan build-outs coined by Rem Koolhaas in his “Typical Plan” essay from 1993 about office architecture, and smaller personal units of furniture produced and sold by IKEA, Herman Miller, or Steelcase. This material mimics and embodies the aspirational notion of being a fit for everyone. So, I would like to think that some of my concerns around conversations about race and how workers are figured or not, made visible or not, are elaborated upon through this hyper-market-driven material in architectural space.

Jessica Vaughn, 28″ x 22.75″, 2018, offset prints on newsprint, plexi and hardware, 28 x 22.75 inches [courtesy of the artist and Martos Gallery]

MA: Is this something you’re hoping that visitors feel as they’re walking through?

JV: Yeah, I hope there’s a sense of something being modular, or of these grid formations that we somehow take as being normative or inherently inflexible. The idea is that visitors are able to walk through the space and get a different sense of situating themselves through what is considered typical architecture.

MA: And in terms of the materiality of your work, and how it relates to labor, much of your practice includes discarded or surplus materials, architectural fragments, and essentially remnants of people’s labor and presence. How does that connect with this new work?

JV: I think that there is an interesting way in which objects that have circulated through spaces have a matter-of-factness about themselves. These are the things that over time are reoriented, augmented, shared with others, and in indirect and sometimes very subtle ways show the process of how something is constructed, made, and exhausted.

My sense of what I like to make comes from understanding materials that I’ve used and my experiences in different work environments. There’s something about using decommissioned materials taken from the state and bureaucratic resources that call attention to process, and specifically an overworked body, a system that is sort of treading along, sometimes disrupted by change, but often remains status quo. Wedging myself into these systems to procure this material is the first disruptor, and I create works by moving through research of records, cultural and political writings, and working with materials in the studio. The materials that I procure highlight and illuminate systems of repetition, space, rhetoric, and language that in the long run dictate how people participate in society as workers and consumers.

MA: In creating your works, do you think about how corporate infrastructures affect the body? You spoke about the overworked body. In some ways this is visualized through the actors in the diversity training videos. I’m wondering about how the body or embodiment relates to your work, in its creation but also as something that people encounter.

JV: There’s this idea that anyone should be able to occupy these spaces, but there are many ways in which racial differences, and whiteness as a construct, make this virtually impossible. And I think the text in the videos, although dated, begins to make clear how the aspirations for capital inherently fall short at correcting discrimination. The texts used in the video are streamed together from a number of diversity training videos and cut together in different patterns and sequences. The footage used in the video consists of groupings of found footage from these training videos and footage I shot in different office spaces. The staged nature of the footage heightens my awareness of the artificial relationship between the content of the video and the actual workers in real life. And I think that the regulations and compliances within the ideological concepts of various institutions dictate how we act, move, and interact with others. These forms of compliance and the minutiae of these ideological concepts that start off as texts, laws, jurisdiction writing, some form of a script or proposal, become invisible once a material object is produced. It then reveals itself again through the direct action someone might have with architecture, infrastructure, or products—everything really.

Jessica Vaughn, Visible Hands (still), 2018, digital video, 3:48 minutes [courtesy of the artist and Martos Gallery]

MA: I like how you’re drawing attention to the texts by overlaying it in the video. It draws attention to that gap between theory and practice. It is sort of echoed in the spatial installation as well. Your displaying of the infrastructure doesn’t transform the space. You know it’s a gallery, so what you do is place corporate and infrastructural materials within another structure, in this case a museum or gallery.

JV: Exactly. These spaces share commonalities both materially and in practice. As an artist who benefits directly and greatly from cultural institutions, I think that there’s a way in which I approach these ideas from a sense of care, an interest in seeing art and cultural institutions function differently and more equitably. These intersecting issues of economics and representation are not just theoretical points of interest but are actual conditions that exist in the world through material and aesthetic decision-making that has real consequences.

Magdalyn Asimakis is a curator and writer based in Toronto. She was recently a curatorial fellow in the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program and is currently a PhD student at Queen’s University. She is the cofounder of the collective and roving project space ma ma, based in Toronto’s west end. Her writing has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, Artforum, and Canadian Art, as well as museum publications by the Whitney Museum, the New Museum, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Jessica Vaughn received a BHA from Carnegie Mellon University and an MFA from the University of Pennsylvania. She was an artist-in-residence at Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture, Skowhegan; Lower Manhattan Cultural Council; and the Whitney Independent Study Program. Her upcoming solo exhibitions are at Dallas Contemporary (2019) and PATRON Gallery, Chicago (2019). Selected exhibitions include Post Institutional Stress Disorder, Kunsthal Aarhus, Denmark (2018) Exit Strategy, Emalin, London (2018); FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art, (2018); Omnipresence, The Kitchen (2018); Receipt of a Form, Martos Gallery (2017); Material Deviance, SculptureCenter (2017); Round 39: Looking Back, Moving Forward, Project Row Houses, Houston (2013); and Fore, The Studio Museum in Harlem (2012). She is a 2019 Graham Foundation Research Project grant recipient, and a 2019 participant in Printed Matter’s Emerging Artists Publication Series. She was a 2018 New York Artadia awardee.