Jesse Darling: The Ballad of Saint Jerome

Jesse Darling, Installation view, 2018 [photo: Matt Greenwood; courtesy the artist and Arcadia Missa, London]

Share:

In Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation, artist and activist Sunaura Taylor speaks from her own experiences toward a kind of crip cross-species solidarity. Human ableism is often projected onto animals, she writes, when a more freeing project would be “to claim the animal and the vulnerable in ourselves.” Jesse Darling’s sculptural interpretation of the tale of Saint Jerome and the lion shares something of this spirit, inverting the ideas of what it is to be human, what it is to be healthy.

As Darling retells it in an artist statement accompanying their first institutional solo show, when a lion turns up roaring outside Jerome’s cloister, “the monks go for the crossbow to kill it, but Jerome alone raises a hand: this lion is just wounded!” He finds a thorn in its paw, removes the thorn, and nurses the limb, after which the lion stays by his side, tamed. This parable of power and care formed the theme of Darling’s printed project for Artforum in 2018—iPhone images of left-handed drawings and object arrangements set up at home like prayer pieces, the scale of art that was possible during a period of acute pain and the paralysis of the artist’s right arm—and is developed here in three dimensions, after a measure of rehabilitation.

Unlike Jerome and the lion’s representations throughout art history, particularly in the Renaissance (Antonello da Messina’s ca. 1475 perspectival painting or Albrecht Dürer’s 1514 engraving, both depicting Saint Jerome in his study, are canonical examples), here the body of the saint is not visible. The hermetic scholar is represented only via his comically insufficient props—toilet brush staffs, bloody cut-finger pens—and a severed orchestra of gray hands. Like switchy superheroes and their alter egos, the saint and the scholar cannot appear side by side in this staging, for they are not only companions in the making, their beings are one and the same.

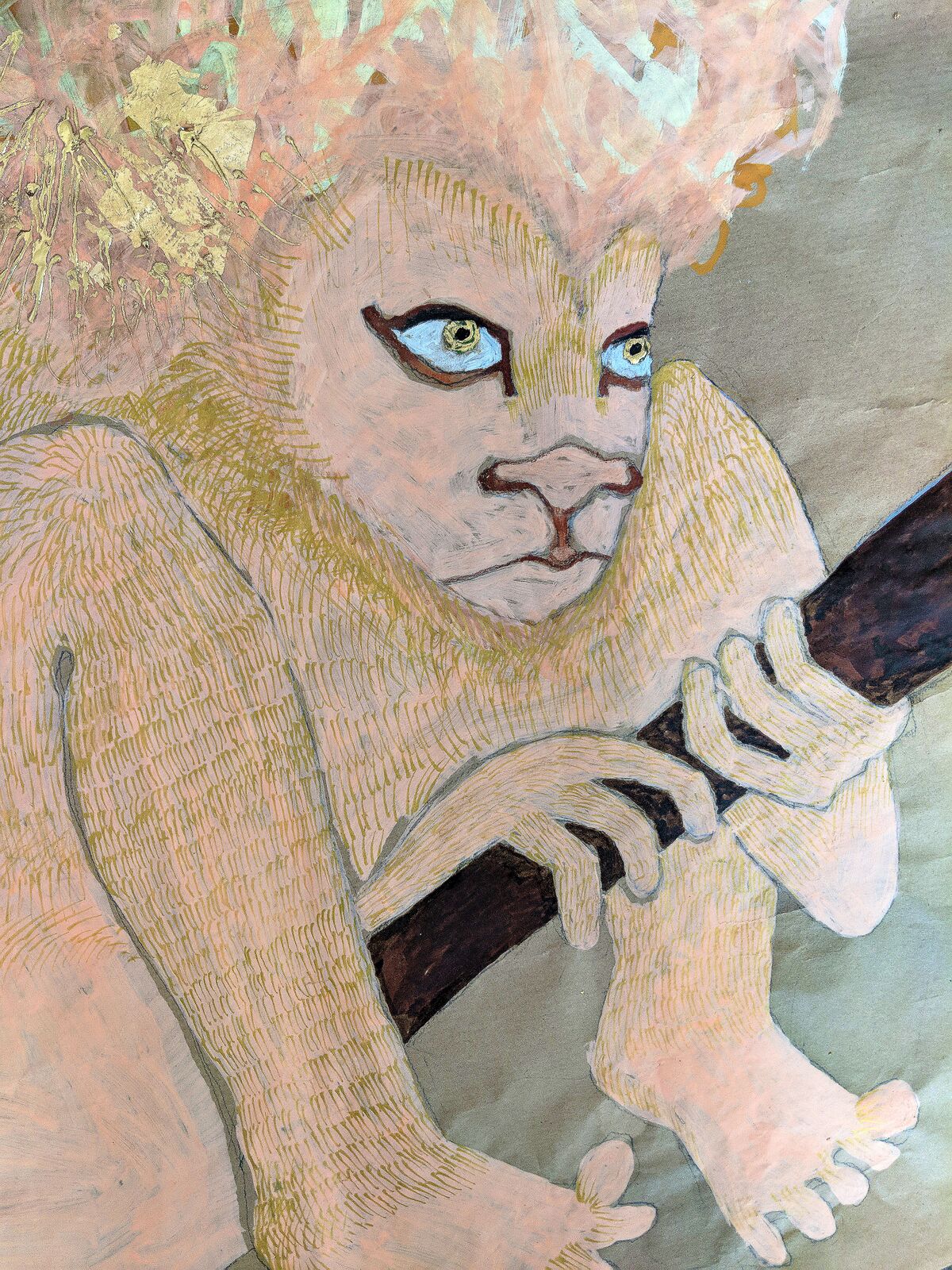

In Lion in wait for Jerome and his medical kit (all works 2018) the lion crouches, drawn and painted on a piece of packaging paper torn out of what could have been the complete picture. With golden-penned mane and fierce eyes, it brandishes a spear as if in self-defense. On the facing wall, The lion signs “wound” is a marker drawing of a lion making a two-handed gesture next to a 3-D–printed hand whose poking index finger bores a hole in the frame’s glass. The works raise the question of whether Jerome’s interventions, however benevolent in intent, were welcomed by the animal.

Other lions seem sick from the bondage of service. Two wiry, whitish sphinxes, like ones protecting the sovereignty of some municipal building, guard the room’s entrance but lack any pride. One bears its wounded paw, a ball gag in its mouth; one is hooked up to a canister, perhaps to prevent asphyxiation within its vitrine. Compare these two to the noble, intertwined feline faces of Le Baiser (No More Saint Jeromes) (2017, made independently of this exhibition), and the sentries at Tate appear emaciated in captivity. A muzzle for an animal hangs with grace from a meat hook (Regalia & Insignia), aesthetically similar to the BDSM gear in other artworks here. The restraint of the garment is carried through the minimal composition, suggesting a dynamic of domination and dependency, in either human or animal realms.

Jesse Darling, Lion in wait for Jerome and his medical kit (detail), 2018, paint pen on packing paper, gold leaf, parcel tape, 28 x 43 inches [courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa, London]

The ever-presence of fallibility within outward presentations of strength or success—and the inverse, tenacity within what is perceived to be weak or failing—is embodied in the exhibition’s motley mythical cast. Two Brazen Serpents are molded from mobility canes made flexible, whereas the legs of once-sturdy display cabinets half-collapse under the weight of their concrete contents. Little Icarus, who “does the most,” is bent over to become fluid paint running down a canvas, his would-be fall cushioned by tiny packets of air (Icarus does the most (temporary relief)). What goes up, must come down, sing colorful paper planes; what is gripped too tight must be released, signs an articulate hand holding a lion bone in a masturbatory pun; everything “whole” will eventually be undone.

As a whole, the off-kilter myth-scape offers no monumental effect. At the other end of the hall is a clutter of steel crutch trees with empty ring binders upturned on top (Saint Jerome in the Wilderness). Their lankiness recalls the artist’s earlier tackling of knowledge as power in the towering school chairs of March of the Valedictorians (presented at Frieze London in 2016). Behind that sparse forest is a knocked-through hole in a temporary white wall—peer within, but there’s nothing to see. The many icon-sized wall-works offer more nourishment against emptiness, their scale like that of religious portraits with one or two main figures and details that invite close-up study. In the bottom of their deep-set frames, devotional offerings from hardware suppliers are scattered like humble charms.

Jesse Darling, Installation view, 2018 [photo: Matt Greenwood; courtesy the artist and Arcadia Missa, London]

Jesse Darling, Installation view, 2018 [photo: Matt Greenwood; courtesy the artist and Arcadia Missa, London]

If the therapeutic potentials of art and religion are aligned, it is no thanks to their institutions, but rather to a faith in the intimate exchanges they might host. Instead of the old Christian relics’ gold leaf, these “temporary reliefs” adopt aluminium foil, engraved, scored, and painted over with scenes of malleable archetypes. Darling’s queer variations on Batman—another hero usually filled with hubris—feature in this format: once feminized and wanting with pastel flowers and a gaping wound in the middle (Our lady Batman of the empty center); once kneeling in the tender company of another lion and cradled bat-babe (The Lion and batman in the garden). The gendered or humanized features of the figures are specific but interchangeable; each wants to be special, and also not alone. Within the lofty room of the arch museum, valor gives way to vulnerability.

This review originally appeared in ART PAPERS “Disability + Visibility,” Winter 2018/2019.