Jared Buckhiester: Male Trouble

Jared Buckhiester, “the king flower of his flock (cigarette),” detail, digital c-print, 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

Across mediums including drawing, sculpture, and photography, Jared Buckhiester’s artwork is populated by figures and symbols laden with the weight of troubled American masculinity. A feeling of tender longing, however, balances the subtle violence and macho aggression suggested by images of sailors, cowboys, teenage wrestlers, and pocketknives—a bittersweet contradiction familiar, as the artist mentions, to anyone who has ever had a crush on their bully.

Buckhiester and I each grew up as queer boys in Appalachia—North Georgia and East Tennessee, respectively. As the artist was graduating with his BFA from Pratt Institute in 1999, I was beginning to experience some of the pre-adolescent confusion he would later depict in his drawings. An untitled drawing from 2006—the year I started high school, terrified and excited about being in the locker room before my freshman wellness class—shows two teen boys dancing in ballet shoes and tights while another figure in a T-shirt and jeans slumps on a nearby couch, possibly bored or annoyed. One of the boys holds a knife, and what appears to be a chicken hangs suspended from the entrance arch, as if slaughtered for an occult offering. The scene is both funny and slightly sinister, and I imagine a younger version of myself seeking the company of this trio of misfits.

When we spoke over the phone earlier this summer, we began with these memories and drawings of queer boyhood. We also discussed the thrill and humiliation of attraction, the influences of Billy Budd and Querelle on Buckhiester’s current exhibition, and the question of how much of a person’s “arousal template”—the fantasies, thoughts, images, sights, and smells that turn you on—is given, rather than chosen. The transcript of our conversation has been edited for publication.

Jared Buckhiester, Untitled, 2006, graphite and ink on paper, 20 x 26 inches [courtesy of the artist]

Logan Lockner: I’m curious to hear about your experiences growing up in North Georgia. Some of your early drawings feel really familiar and resonant to me, having grown up as a queer boy in a small Southern town—or just a small American town, maybe—and confronting these sorts of masculine archetypes. There was some sadness in those drawings, but also humor and self-reflection.

Jared Buckhiester: You know, it’s funny, because I have a different perspective on those drawings now that I made them a long time ago. When I was making them, I initially wanted to make drawings of things that I couldn’t photograph, because what I wanted to talk about were memories, and it wouldn’t make sense to recreate them with people in photographs. I started making these drawings and then embellishing them, maybe even making revisionist versions of the memories, once the imagery got more clear.

There was a moment in middle school when [most of] my friends were girls, and I was doing chorus. I had lots of friends that were boys too, but I was like, “Unless I play football and figure out how to be friends with them, this is going to be a really different experience for me here.” I was able to shift and sort of assimilate through gesture, and the things that I chose to listen to, and the things that I was interested in. Some of that was really authentic, and some of it definitely was performative. I learned drag—straight drag—at an early age. These drawings were a way to sort of be very affectionate to the part of myself that didn’t want to change.

What would it have been like if I had total freedom with those impulses? Having a lot of affection for those parts of myself, when I was making those drawings, took a while. Growing up there [in North Georgia] was definitely something to recover from, even if it was also so beautiful and magical. I think making these drawings was the beginning of me recovering the parts of myself that I knew were the best, you know?

LL: I was struck by what you said about masculinity being both performative and authentic. It’s not a black-or-white or binary thing, in terms of fitting into one camp of stereotypes or the other. That tension between performative and authentic dynamics of gender plays into a lot of your other work, too. I particularly had these questions about the photos of truckers on the highway. It’s interesting to hear you say that you were working in photography back then, and then photography has made a [more recent] appearance in your work as well.

I’m always thinking about the opening of Christopher Isherwood’s The Berlin Stories (1945), which, of course, went on to be the basis for Cabaret (1972). But that book starts out with the narrator literally saying: “I am a camera with its shutter open”—sort of compartmentalizing this queer consciousness as photography, in a way. I felt like these trucker photos were maybe one of the best expressions of that idea, in the sense that these photos are of the gaze, even though the gaze isn’t directly represented in the photo. It almost kind of felt like cruising, too, like you are taking a picture of cruising.

Jared Buckhiester, “the king flower of his flock (cigarette),” digital c-print, 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

JB: That work was like a reenactment. I always travelled to visit my family with my camera or drawing supplies—for a long time. My dad was driving me back to Atlanta on a stretch of highway in South Carolina that I’ve ridden on many times, and I had my camera, and I just started shooting the truck drivers as we passed them. I shot tons of pictures. It was high speed. My dad is driving, and I’m basically trying to get him to chase down truck drivers while I’m in the backseat. He is kind of aware of what’s going on, but I am basically shooting super high speed, with a sports lens. I have no idea what I’ve got until I’m editing it, but I knew that there was something because it was so thrilling to recreate this thing that I’d been doing since I was a kid. It was basically like dads on thrones, everywhere.

Then, when I was editing them, there was this deep feeling of humiliation. It was really intense because inevitably there was a frame where they were making eye contact with me. I really felt like I was being seen, I was being caught. There are so many other possibilities, but that was my initial experience of them. I also felt like I owed [them] an apology or something, because it was such an overt objectification—invading their space. So I made some ceramics to pair with the photographs. The ceramics are these urinals. They’re sort of like an atonement and a transgression at the same time.

LL: I wasn’t putting that together before. I saw the trucker connection, but they sort of function as an apology or a sort of offering, in a way.

JB: Yeah, that was the initial impulse to make them. I just saw that space to be so charged—the landscape of where I’m from, it’s so intensely moral. Not only did I feel like I was messing with those morals, but [I was] feeling real emotions while I was doing it. That felt really rich. I’m reusing the trucker photographs—two of them—in a new context, with a new group of work right now, in an exhibition called too fair-spoken man. It’s all based on [Herman Melville’s novella] Billy Budd and Querelle (1982).

LL: Oh, that is really nice—I was going to ask how the truckers are sort of [an] American variation on macho stereotypes or archetypes, like the sailor or the soldier.

JB: Yeah, at the time I was thinking of the cowboy.

LL: Yeah, of course.

Jared Buckhiester, “the king flower of his flock (soup),” digital c-print, 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

JB: So, Billy Budd … I don’t know if you know this story, but the captain is a really isolated, very masculine, homosexual figure who is tormented by desire. [The situation] sort of fractures these really hierarchical structures of the ship—his desire, and also the beauty of Budd. The truck drivers just seem like they fit in that context, and also, they are sort of suddenly like everymen.

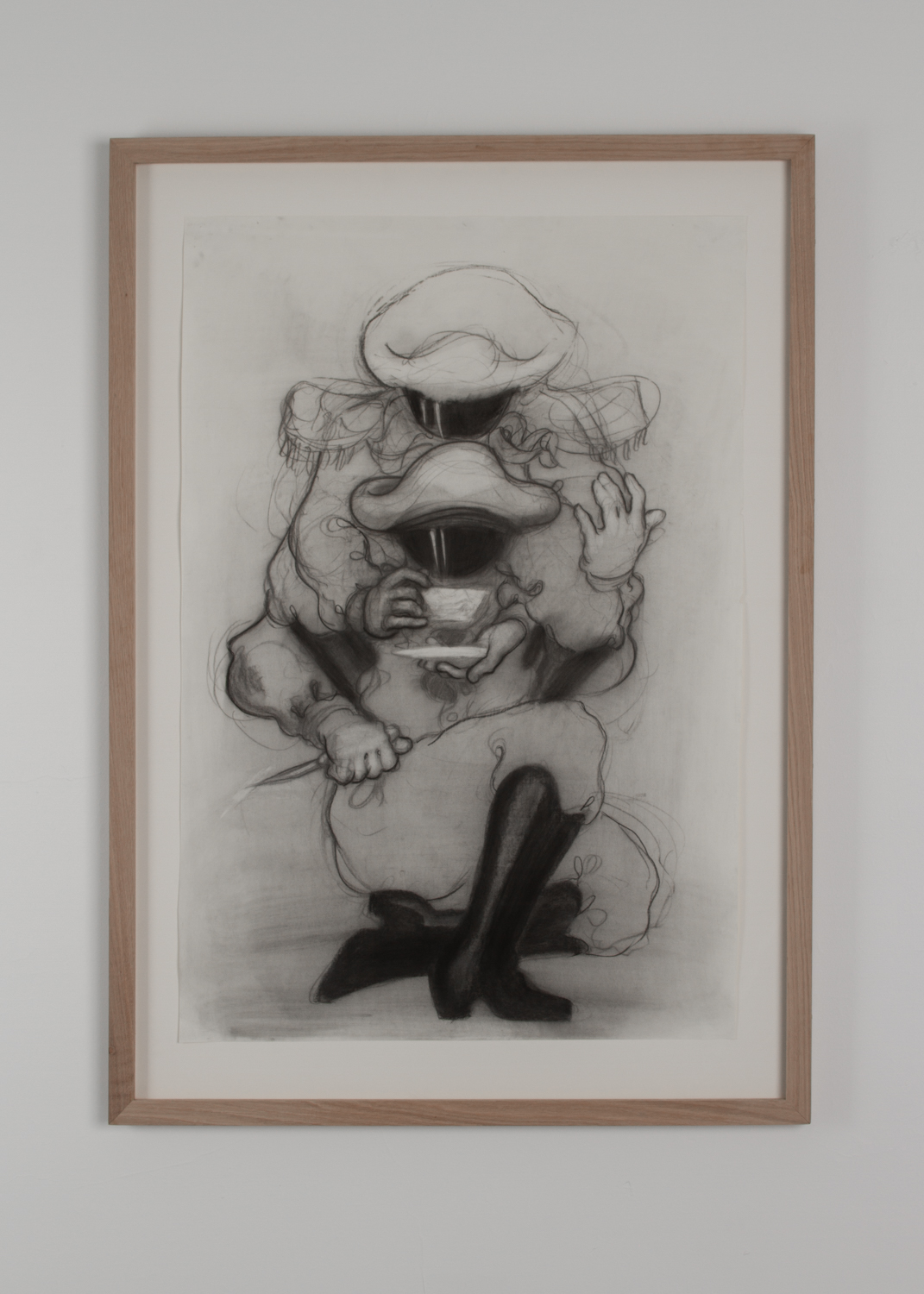

Also, too fair-spoken man was about consuming. It was about these solitary figures [who] are nurturing themselves. The truck driver photographs I chose were one with the cigarette and one holding a can of soup. It fit again. It’s nice to re-envision them, and also to rename them. Originally, they were all named Subject or Object, with where they were taken and the speed that they were going. The name of them now is taken from Budd. It’s called The King Flower of His Flock. It just changes them.

LL: I’m curious about how you approach working across so many different mediums, and how you make decisions. I guess [pairing] the urinals and the photos is a really good example of this, but maybe you could speak about it a little more. It feels like the questions you are pursuing remain remarkably connected and coherent across these different mediums. I am curious to hear about how you make those decisions. Maybe it’s not a totally rational or conscious process and it’s more intuitive [or] playful.

JB: I think it’s impulsive, or even compulsive, rather than playful. I mean, I went to Bard for sculpture. Even before that, though, I was kind of thinking that the material is so much of the content. It’s like one of the characters of whatever it is that I am making. I think in such narrative terms. So if there is something that I want to pursue or render, then what is the best material to do that in? A lot of it is just instinctive: Trusting my subconscious to move forward with a form. The trucker and ceramic thing was something that evolved over a year of having the trucker photographs and then being like, What will the gift be? and What will it be made out of? That was the most conscious decision-making around that, as far as how things would be shown together.

But when it’s time to show, I step back and look at the things I’ve been making and think: what are the nicest gaps and suggestions that could happen between the materials and images that I’m going to choose? The titles also function that way. Titles don’t show up until I’ve chosen which works go with which works, a lot of the time. The titles are another element of this collage of things that go together. I just want everything to sort of ricochet off one another in this way that is connected, but also open and suggestive. My subconscious is so activated when I’m making things and making decisions, and I want the same to happen when someone encounters the work, even though it’s allegorical or symbolic.

Jared Buckhiester, “His duty he always faithfully did,” gray and brown stoneware, 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

LL: There was something in the text for [your 2019 exhibition,] Refusing to Shake, about the wrestling-inspired collages and prints, that says these works are “reflections on the tenacious, erotic hold of images about which we know better.” I thought that was such a good description of what it feels like to be a gay man looking at a lot of imagery that is erotic. So many of the masculine archetypes that are still present and have always been present in things like gay porn also have connections to things that we would recognize as being violently masculine, often, in the real world. There is that tension there.

JB: Yeah. An arousal template is deeply problematic. But it’s a given, it’s not chosen. It’s like the color of your eyes. It’s from the makeup of family, culture, circumstance, things that happen to you, things that are available to you. I think that I’m really interested in that trouble. Also, the work is questioning—I think toxic masculinity is kind of a reductive thing to say, but I don’t know a better way to talk about it—being attracted to things that are aggressively problematic in culture at large. It’s like, you know, queers who are in love with their bullies. I’m thinking about that a lot. These vessels that I made are characters from Querelle, but in states of real submission, like starving and trying to feed themselves with snake and corn and stuff like that. It’s subjugating that, but not in a fetishistic way. Maybe humanizing masculine forms. Trying to create some sort of tenderness or affection that is not erotic around them. It’s sort of like why I chose the truck driver who is missing fingers and eating soup.

LL: Yeah, encountering them just as human beings.

JB: Yeah. I don’t know if I’ve answered it in a direct way, but that’s kind of the way I’m thinking about masculinity, as created to desire. I used to feel protective of it. It’s sort of like [Robert] Mapplethorpe. Mapplethorpe is horrific because he was a capitalist, not because he was attracted to objectified men of color. It’s more that, his capitalism grosses me out more than his arousal template because [the latter is] not political. It is—easily, it’s political and problematic —but it’s not as if it’s chosen. What you choose to do with it— But the initial impulses? I don’t want to say anything else. [laughing]

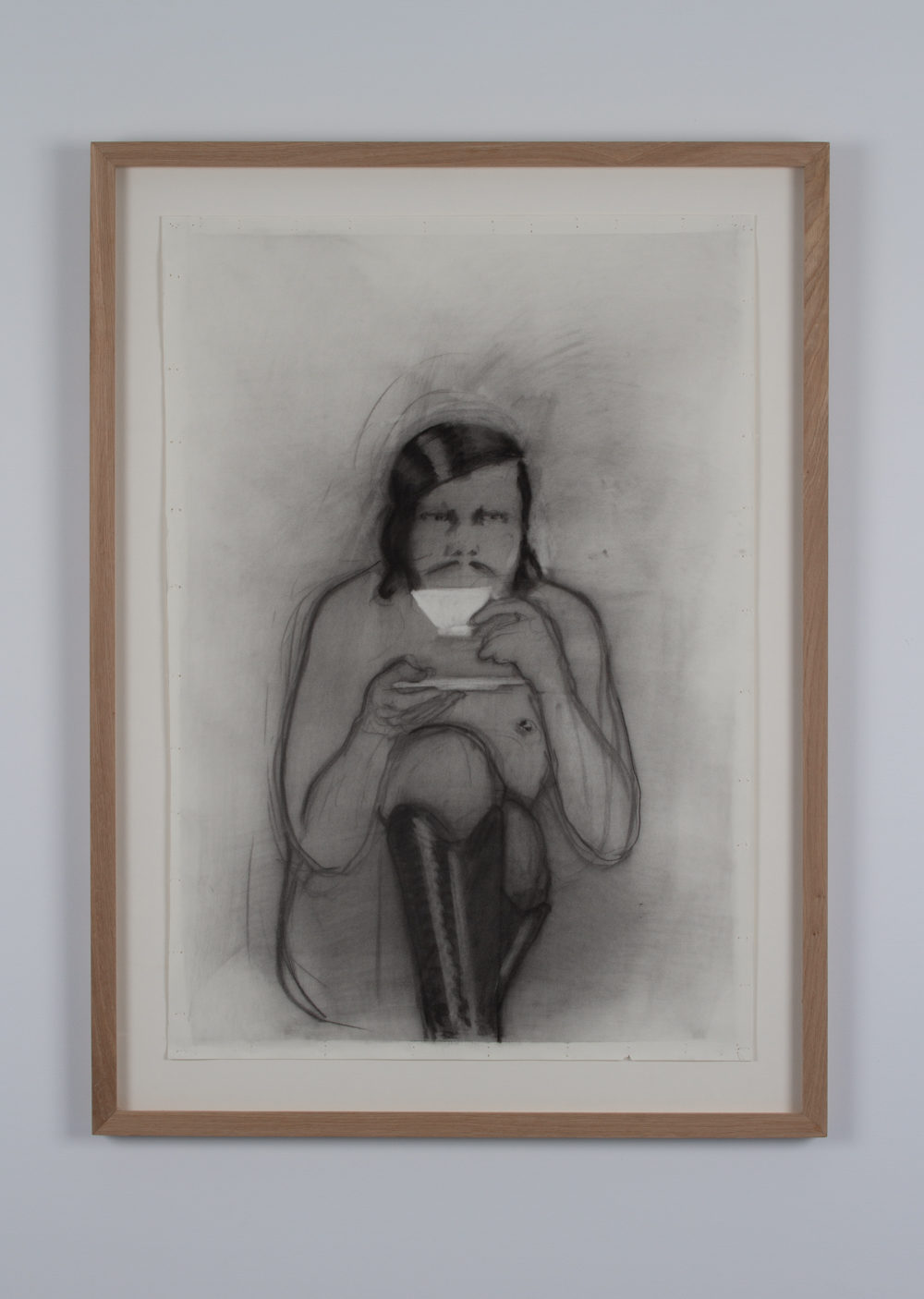

Jared Buckhiester, “our new-made foretopman,” charcoal on paper, 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

Jared Buckhiester, “Across the river of creeping vines, help me I am coming to your shore,” charcoal on paper, 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

LL: It feels like a lot of these works are documents of those moments. I really like this phrase that you’ve used a couple times, arousal template, which I haven’t heard before. But it feels like you are capturing that moment when the impulse is there, before it has been rationalized or articulated in a way that feels acceptable outside of your own head. I guess that’s part of what I appreciate and recognize in these works. It’s what you said earlier, you feel both seen and caught at the same time.

JB: It’s like, I don’t want to interrupt the impulse, but I also want to take away its power, or something.

LL: Yeah. I think being able to see [how] sometimes that impulse is—like you said—a result, or a given, and not chosen, allows for a different type of reflection, because you are not so interested in shaming or punishing the impulse. You are just curious about it and what it might mean. I think you used the word trouble earlier. You are interested in that trouble. But it’s also one of those things: Finding a solution or neat answer to sorting and parsing that out probably would also be unsatisfying.

JB: Yeah. I agree. When I’m choosing what things to put together, it’s charged, but it’s also like, How do I look at this in objective terms? Because the connections aren’t exactly visible yet. You are put into an objective state to consider all of it, instead of a reactive one, or something. I’m definitely not trying to get people aroused.

Jared Buckhiester, Too Fair Spoken Man, installation view, 2021 [courtesy of the artist]

LL: Do you have a future project in the works? Or developing questions?

JB: I’m constantly making different things. I’m making lots of watercolors of pocketknives at the moment. But these charcoal drawings and these ceramics are still happening in my studio, and the vessels—I’m still making them. But when I’m making things, I’m not imagining them in an exhibition space until it’s time to put them in one. I keep that real fluid [so] that things can change and develop.

LL: What drew you to the new watercolors of pocketknives? Again, that’s a very potent object and symbol from my childhood that I can definitely relate to.

JB: Well, it’s funny. Covid started and I wrote a short story that is basically a memory that I have revised. I used to collect pocketknives. My sister had a boyfriend who was a Navy SEAL. He came to visit our family for the first time, and he gave me this giant knife as a gift the first time I met him. He was like, “We should work out together in my bedroom.” It was horrifying. It was really scary actually, just because it was so intense. I wrote this story that gives the fourteen-year-old me all the power, and I was imagining the illustrations for the story. I don’t think that they actually will be illustrations, but that is how it started.

Logan Lockner is a writer in Atlanta. Previously, he was editor of Burnaway. His writing is included in the forthcoming monograph Toyin Ojih Odutola: The UmuEze Amara Clan and the House of Obafemi (Rizzoli Electa, September 2021).