James Allister Sprang: a breaking from, a breaking with, a breaking out

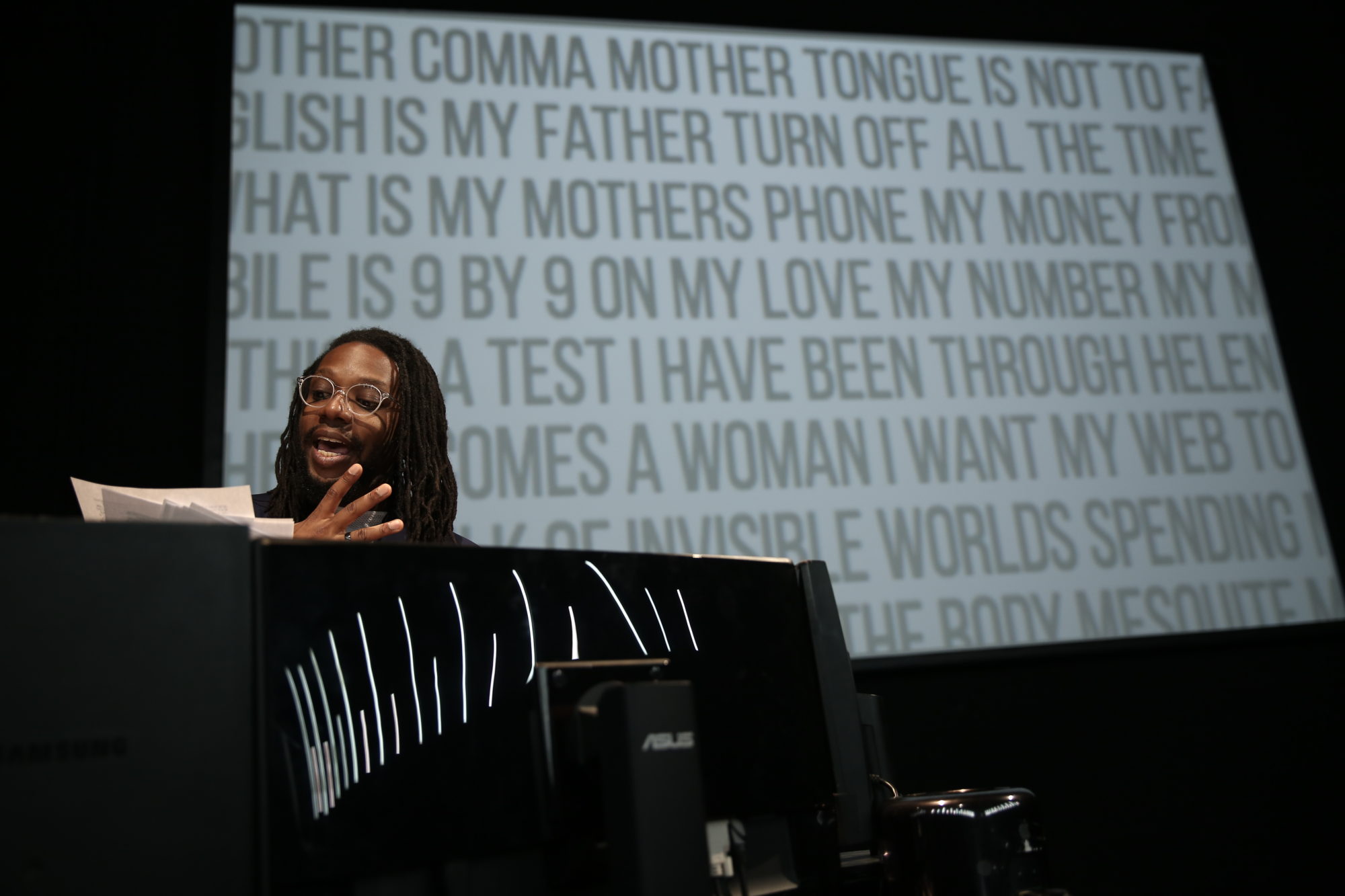

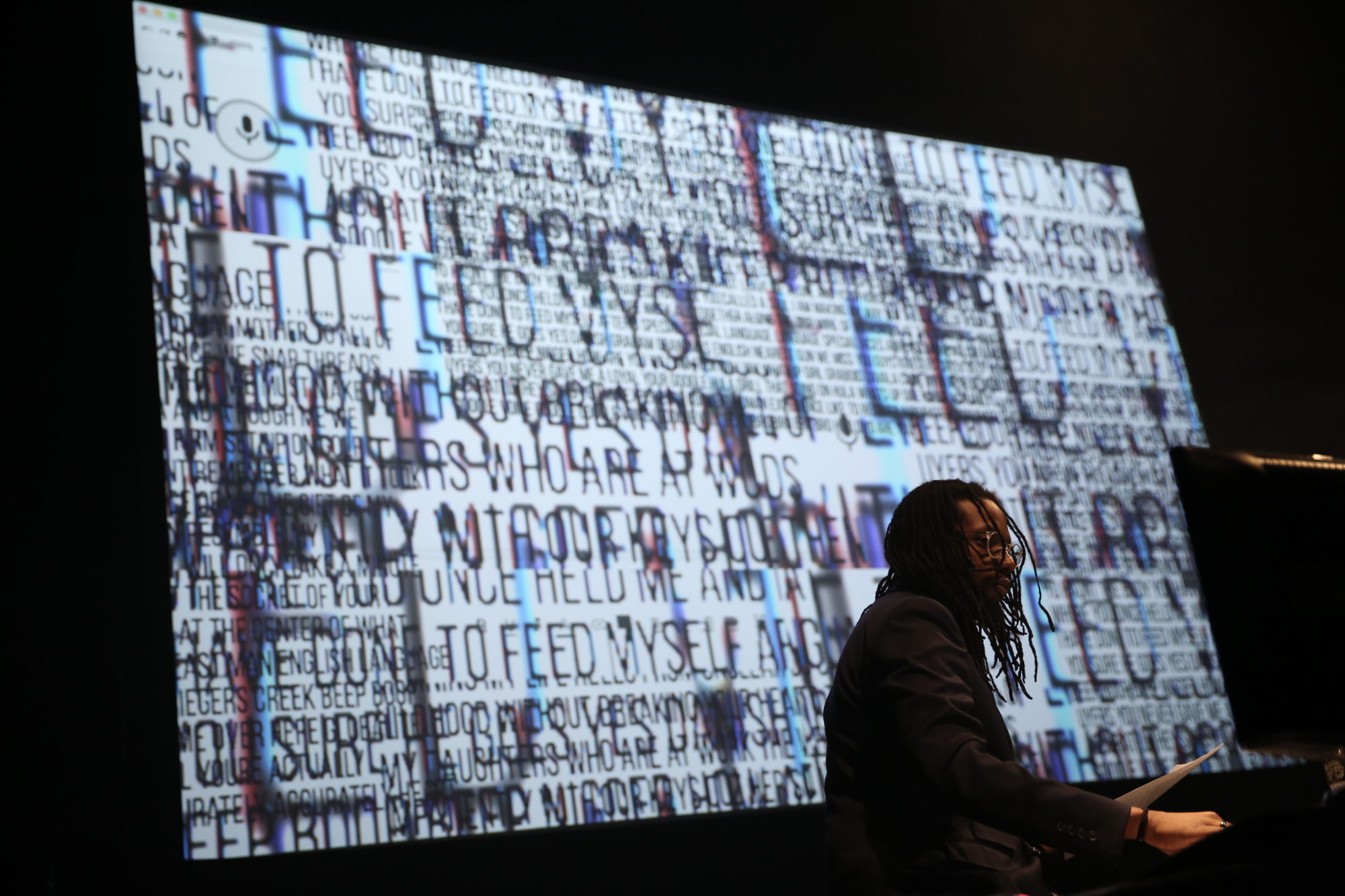

James Allister Sprang, installation view of Turning Towards a Radical Listening, video, 2019 [photo: Paula Court; courtesy of the artist and The Kitchen, New York]

Share:

James Allister Sprang’s sculptural sound installation Turning Towards a Radical Listening emerged from his residency at The Kitchen, during which, conversations with poets including M. NourbeSe Philip, Rachel Eliza Griffiths, and Tracie Morris became samples in a voice-to-text performance of culturally biased algorithms. Asynchronies and breaks act simultaneously as points of racial reckoning and poetics. Sprang shared how this project emerged and evolved throughout his residency in the following conversation.

Laurel V. McLaughlin: You’re coming off … a string of residencies at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, New York; Fountainhead, Miami; Shandaken: Storm King, New Windsor; … MONOM, Berlin; and then, most recently, at The Kitchen. Could you share how Turning Towards a Radical Listening (TTRL) emerged and developed through these residences?

James Allister Sprang: TTRL is this weird brainchild I had two and a half years ago. Ultimately, I wanted to facilitate a sonic experience, feeding that sound into Google’s auto-dictation software so I could write in the tradition of flarf and concrete poetry, while also observing and revealing the biases of the program.

The project sits at the crossroads of chance, political commentary, poetics, sound art, and theory, all housed under the umbrella of a black experimental tradition. Many of the moving parts required detailed attention and skill sets that I needed time and space to develop. For example, the Wave Field Synthesis array that I use is an advanced sound system that creates sonic holograms. It was custom built by Bobby McElver and Andrew Schneider, and there are only two others in the United States. TTRL will be the first use of such technology in the visual art world. As you can imagine, there was a big learning curve …. I outlined the things I needed to learn and get done, while thinking of each residency as a steppingstone towards a finalized project.

LVM: TTRL is a durational work with performances informed by conversations and other residency components. How are you imagining that this will unfold at The Kitchen?

JAS: I have been recording conversations with poets as a way to generate sonic material, but more importantly it’s a way of holding space for the work many of us are doing while making new intersections. The three conversations we will have at The Kitchen with M. NourbeSe Phillip, Rachel Eliza Griffiths, and Tracie Morris will really help create a framework for audiences that choose to engage.

For example, the conversation I had with NourbeSe was both generative and healing. The event involved a group reading of “Zong!,” in which the audience engaged with that text, sound, and space, along with a conversation that unpacked NourbeSe’s complex relationship to the English language and the sounds of speech. Holding space for that type of rumination is what this project is all about.

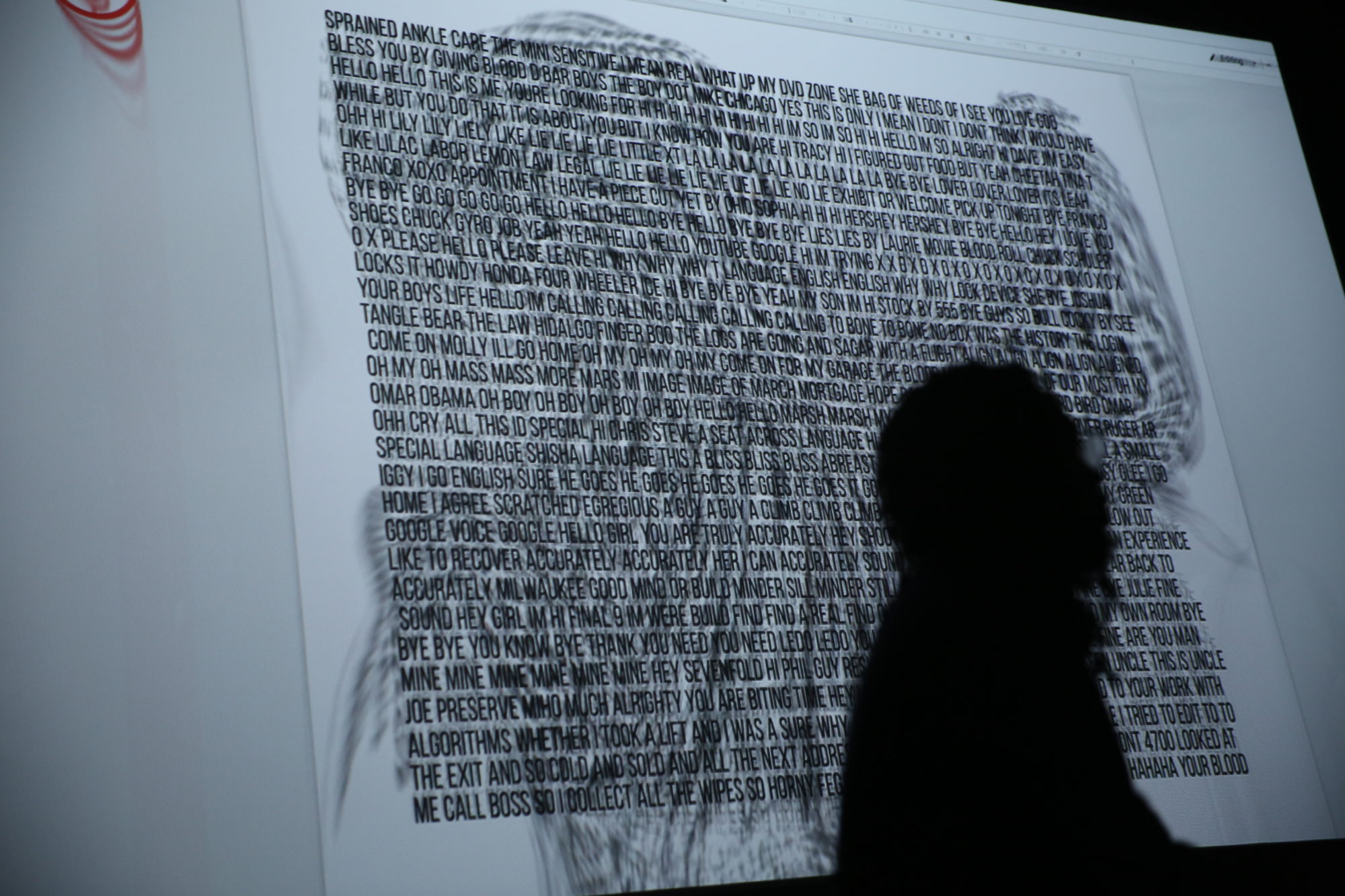

James Allister Sprang, installation view of Turning Towards a Radical Listening, video, 2019 [photo: Paula Court; courtesy of the artist and The Kitchen, New York]

LVM: Before delving further into Turning Towards a Radical Listening, I’d like to highlight a through-line in your practice. You’ve been called a “polymath” when it comes to your intermedial approach, drawing upon numerous forms, disciplines, and traditions including concrete poetry, hip-hop, auto-dictation software, performance histories, DJ/VJ practices, and more.1 Did this intermedial approach lead towards a “radical listening,” or were there additional disciplines and aesthetic perspectives involved?

JAS: My true “training” in the traditional sense, is in the visual arts—photography in particular. Photography has had a contested history with blackness. Many notoriously graded film for fair skin. Similarly, once digital photography reached a moment of autofocus and auto-recognition, blackness was not considered during programming. So, when I originally ideated this work, it was informed by the history of imaging technology and the worrisome reality that most “auto-recognition” software is not programmed to register blackness. This includes speech-to-text software.

But yes, you’re right—working across forms has forced me to challenge the ways I have been patterned as a citizen, artist, son, lover, et cetera, which allows one to listen beyond the dictation of immediate surroundings. That’s what I think radical listening is: embracing difference to make sense of our interconnectedness, the complexity of the world around us, and its systemic biases.

LVM: I’ve seen your performances using auto-dictation software as your persona, GAZR; but in this TTRL, you’re conspicuously performing as you—“just doing your thing.” How is performing as yourself important for TTRL?

JAS: GAZR is an entirely different project. He’s a poet [who’s] decided to become a rapper so his voice can be heard by a wider audience. GAZR performs various original songs in a way that straddles the performative modes of rapper and lecturer. What those GAZR performances pivot upon are the ways rappers exist in our culture’s imagination. We subject a rapper’s language to a different set of rules, and this reveals a lot about us culturally.

But with TTRL, I found that that the performative strategies I’ve developed while performing as GAZR didn’t work in this piece. There is no need to point to how cultural imagination betrays our biases and blind spots, because the biased programming of Google’s auto-dictation software is generating text that demonstrates this. And this is already projected at a large scale in the room. As a performer in TTRL I am more of a guide, feeding sound into both the ear of the audience and the auto-dictation software.

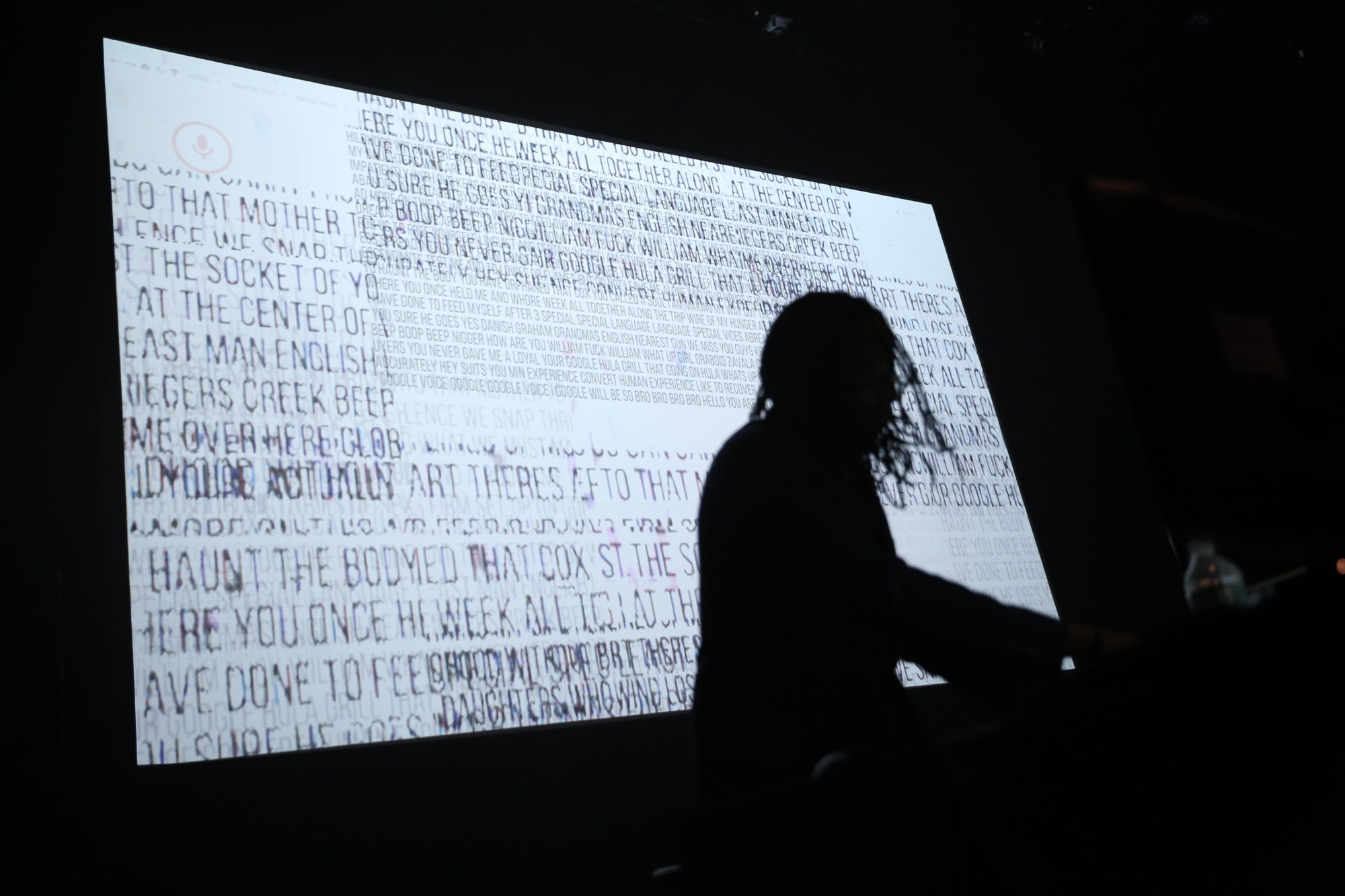

James Allister Sprang, installation view of Turning Towards a Radical Listening, video, 2019 [photo: Paula Court; courtesy of the artist and The Kitchen, New York]

LVM: Much of your practice engages language—that of everyday usage within cultural circulation—and the way it shapes, constrains, and affects people of color. How does language function in TTRL?

JAS: I’m interested in poetics—the slippage possibilities when we are asked to unpack a document. Whether it is a document of gesture, speech, thought, light, contact, presence, et cetera, there is always something lost. And, usually, there is something to be gained, a lesson to be learned.

Unlike “Zong!” or work being done to return to or challenge the archive, in TTRL we have the opportunity to be present as the document is generating itself. We have the opportunity to witness the ways in which bias refuses a true linguistic representation. For many this experience will resonate with their own realities; for others, it may provide a threshold for new and alternative knowledges.

LVM: I recently did an interview with performer and choreographer Miguel Gutierrez, who spoke about language as a double bind for people of color.2 On the one hand, the speaker is forced to use it and the systemic violence that it propagates; and on the other hand, the speaker can register practices of resistance—and I call upon this final term in its most multivalent state, because oftentimes “resistance” can only be understood from the binary of compliance/refusal, but it’s much more complicated. Does this navigation resonate with you, and if so, how?

JAS: Yes, it resonates. How can we take agency over a material that has shaped our lives? It is a complex question with multiple facets, and this project acknowledges the impossibility of “answers,” while providing a balm that might just simply be acknowledgment itself. As if to say, “We are done being gas lit … here is a demonstration of what is happening.”

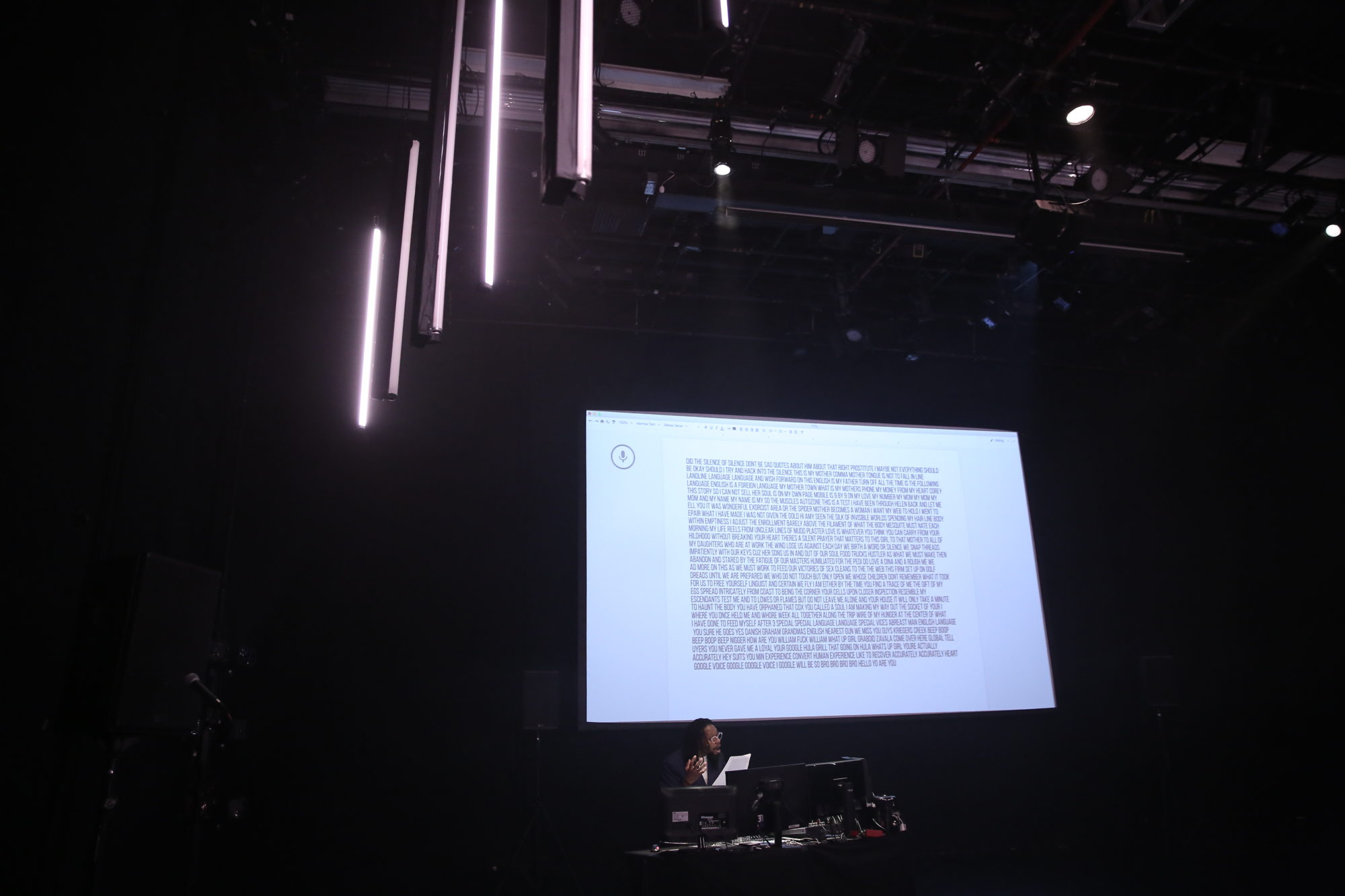

James Allister Sprang, installation view of Turning Towards a Radical Listening, video, 2019 [photo: Paula Court; courtesy of the artist and The Kitchen, New York]

LVM: The performance uses voice-to-text software, altered DJ equipment, and the glitch. Theorists and artists, such as Peter Krapp and Rosa Menkman, among others, view glitches both as failures—a non-register between materiality and meaning, or break in algorithmic stream—and nodes of potential. How does it figure within Turning Towards a Radical Listening?

JAS: That’s definitely interesting, but I’ve been reading other theorists. Yes, I’m interested in the break—a breaking from, a breaking with, a breaking out, a breaking up. The significance of the glitch in this piece is a framing of why we need the break. Though the text that erroneously documents the sound is a major facet of the piece, that’s not where the work lies. The work lies between the sonic experience an audience member will have and the irreconciliation of meaning they generate with that which is generated by the auto-dictation software. It is a simulation of my black experience. It is an experience of constant incompatibility.

If these glitches, the ones an audience will experience projected onto a screen, were a failure to register, they would not exist. What these glitches are is a representation and/or a registration of the margin within the scope of the center.

LVM: Keeping with the technological aspects of the work, it employs 4DSound, further expanding a spatial dialogue that you’ve queried in other media, such as sculpture. Could you talk about your use of immersive spatial sound and how you imagine its affect upon those watching?

JAS: I have worked with one of the few and have made a piece for that particular sound system, but we will be using wave field synthesis for this piece. The idea is generally the same—spatialized sound, but this system produces sonic holograms. For instance, there will be moments when the first row will be able to hear something that the fourth row cannot, as if someone were sitting right next to them or floating above them.

The ear is patterned in so many ways. Challenging acoustic patterns, generating cognitive dissonance, and demonstrating the sculptural aspects of sound really frames the sonic qualities of the voice. This makes the one-dimensional output of the auto-dictation software even starker in relationship to what people will be hearing.

James Allister Sprang, installation view of Turning Towards a Radical Listening, video, 2019 [photo: Paula Court; courtesy of the artist and The Kitchen, New York]

LVM: This idea of “becoming” and process is definite as the auto-dictation amalgamates, but it seems as though there are also layers of interdependence that are embedded within the conversations and technical apparatus you employ—both of which involve numerous collaborators.

JAS: As in life, there is a lot at play. The call to action alone should lead to conversation: let’s critically advance and embrace the world that is spontaneously unfolding and in motion, by ourselves remaining in motion—recognizing and honoring difference. This is an ontological question that becomes a dilemma within a capitalistic society.

To make this piece I have worked with several collaborators, all of whom are brilliant and were extremely generous in their help. This includes Julie Zhu (string composition), Ryan Seelig (lighting design), Matt Romein (projection design), Chloe Alexandra Thompson (spatial sound design), Bobby McElver (wave field synthesis specialist), Aon (sound design assistant), Satchel Spencer (application design), and Sandra Garner (producer). To maintain the critical motion of this piece I have been in conversations with poets such as Raquel Salas Rivera, Amber Rose Johnson, Arielle M. John, Safia Elhillo, Sarah Jane Stoner, and Simone White.

There are so many others I want to thank. If you happen to be reading this, know that I am forever grateful. Everyone involved was willing to take time out of their busy schedules and listen, before lending their perspectives to help create this experience. This project has been written by many.

Sprang’s solo exhibition Fragment Scapes is currently on view at the Knockdown Center [November 2–December 15, 2019].

James Allister Sprang is a first-generation Caribbean American who works across mediums to investigate poetics, performance, gesture, and their documentation. This work is informed by the black radical tradition. Sprang has read, shown, or performed at institutions such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, the Apollo Theater, Abrons Arts Center, the Brooklyn Museum, The Public Theater, David Nolan Gallery, AUTOMAT Gallery, Vox Populi, Baryshnikov Arts Center, Emerson Dorsch Gallery, FringeArts, Knockdown Center, and The Kitchen.

Laurel V. McLaughlin is a writer and curator from Philadelphia, currently based in Portland, OR. Her research interests span visual art, performance, and dance that engage the intersections of embodiment and new media, and her writing has appeared in Performa, Title Magazine, Art Practical, Portland Institute for Contemporary Art’s TBA:19 Blog, Monument Lab’s Bulletin, Antennae: The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture, and various exhibition catalogues. McLaughlin holds MAs from The Courtauld Institute of Art, and Bryn Mawr College, and she’s currently a Ph.D. candidate at Bryn Mawr College, writing a dissertation concerning migratory aesthetics in performance art situated in the United States, 1970s–2016.

References

| ↑1 | Sean J. Patrick Carney, “How James Allister Sprang Transformed from an Art Student to a Hip-Hop Polymath,” VICE, January 6, 2015: https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/wd49px/the-hip-hop-movement-was-art-with-a-capital-a-an-interview-with-gazr. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Laurel McLaughlin and Miguel Gutierrez, “We don’t have illusions that absurdity isn’t the ground floor: A Conversation with Miguel Gutierrez,” Portland Institute for Contemporary Art’s TBA:19 Blog, September 4, 2019: https://www.pica.org/2019/09/04/dont-illusions-absurdity-isnt-ground-floor-conversation-miguel-gutierrez/. |