Interview with Judy Pfaff

Judy Pfaff, N.Y.C./B.Q.E, 1987, painted steel, plastic laminates, fiberglass, wood, paint, lawn furniture, awnings, 180 inches x 420 inches x 108 inches

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS November/December 1987, Vol. 11, issue 6.

Known primarily for her elaborate installations, Judy Pfaff has over ten years of exhibitions in the U.S. and abroad to her credit, as well as sculpture fellowships from both the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation.

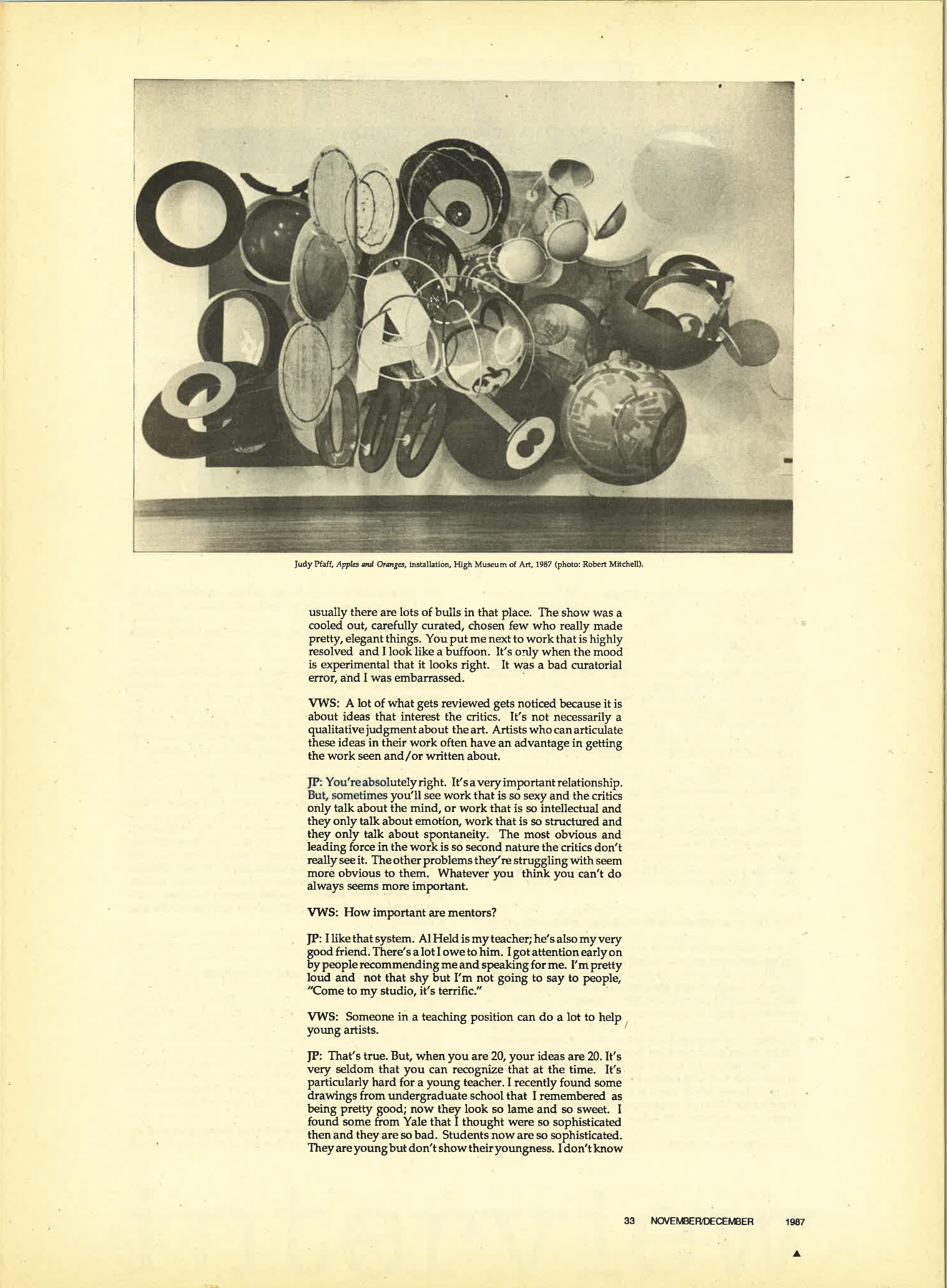

She was recently in Atlanta to install Apples and Oranges on extended loan to the High Museum, courtesy of the artist and Holly Solomon Gallery. Pfaff was interviewed in a piano bar populated by hotel guests attending a national tattoo convention.

Judy Pfaff, N.Y.C./B.Q.E, 1987, painted steel, plastic laminates, fiberglass, wood, paint, lawn furniture, awnings, 180 inches x 420 inches x 108 inches

Virginia Warren Smith: Are you affected by what people say about your work?

Judy Pfaff: I get mortified. I still do. I’ve been showing for a long time and I feel like I keep seeing the same phrases over and over: “Zany.” “Explosion in a glitter factory”—that stuck for six years. The recent reviews and ones from 15 years ago look the same, but the work is light years apart. I used to think that these reviewers had seen only one piece, that it was their first exposure. But most of the people writing now have seen fifteen or twenty.

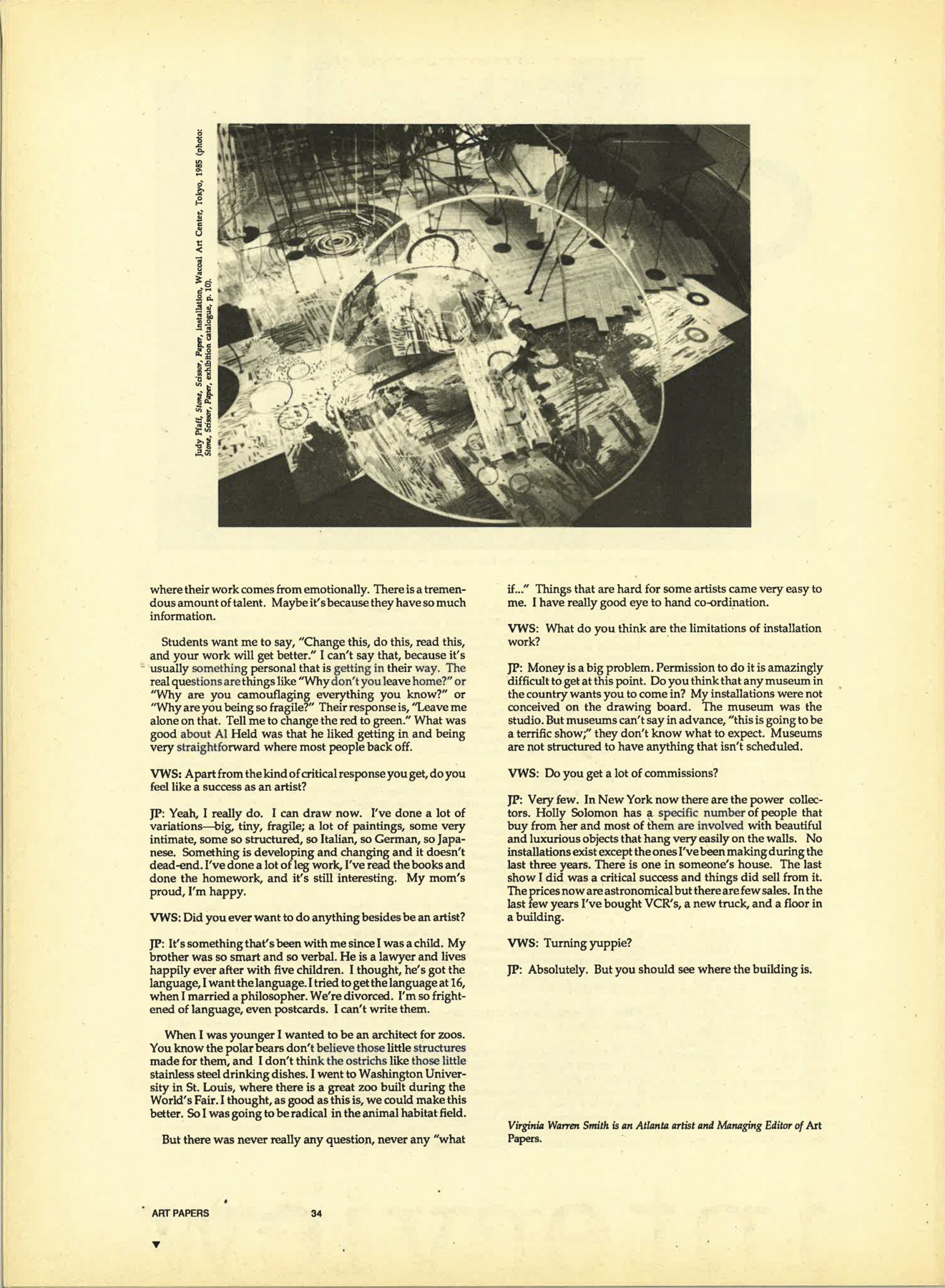

The work does change with every show—structure changes, materials change, the kind of narrative changes, the scale changes. There is a ton of engineering in some of those pieces. People think that I just walk in and staple it together, that it’s just cloth and paper. It’s steel.

People see only that it’s big and colorful. I keep thinking I’m doing something wrong, so I make changes.

Then someone like Mike Brenson, who is very interested in my work, will look at it and compare me to Raoul Dufy. I wonder what kinds of buttons am I pushing with someone who is genuinely trying to look, who is on my side. What is in the work that pushes these buttons that I don’t think are being pushed at all? Dufy waltzes through paintings, and they are beautiful. I’m jamming things in and the color is really straightforward, out of the can— signpainter’s enamel—not seductive. It’s graphic-not that kind of French finesse.

The people who don’t like my work think it is lightweight, that it’s passé or that I don’t have a head on my shoulders. There are so many references in my pieces that look warmly to the past. It makes me seem very old-fashioned and not part of their argument. I don’t kill the father and the mother.

It would be nice if someone could look at work in a fresh way but that never happens. You learn as you become more and more professional, that if the writing isn’t there, if you haven’t caught the imagination of someone who augments the work in print, forget it. We need each other but I haven’t found a way yet to communicate with anyone, either through sitting and talking to them or through the work, that seems accurate to me. Barbara Kruger’s work includes language so, whether she intends it or not, there are words that establish ways of understanding the work. I also think the men know how to control and manipulate the media better. Sometimes when I read reviews in New York, especially if I know the artist, I think that the artist must have told the writer what the work was about.

VWS: What would you like for them to say about your work?

JP: Perhaps something about signs and symbols, or layers. In a David Salle you have layers: you have a dry brush erotic image juxtaposed with a metal hat with a Mickey Mouse overlay. You can count the layers from different styles. And I’ve got pieces with layers: geometric layers, layers that are rendered or about shape making, some that are transparent and some opaque, and references to different kinds of art. So I think that we are living in the same highly cut, edited, layered, collaged, fast frame. Right? Wrong, because Salle’s work and my work don’t have the same look. The look travels more than ideas. The critics balk at the look of my work; if you are not cynical and dry and laid out, your work’s not going to be seen correctly by the intellectual community.

At the Whitney, the last big clunker show I had, I was so wrong in that arena. I was the bull in the china shop and usually there are lots of bulls in that place. The show was a cooled out, carefully curated, chosen few who really made pretty, elegant things. You put me next to work that is highly resolved and I look like a buffoon. It’s only when the mood is experimental that it looks right. It was a bad curatorial error, and I was embarrassed.

Judy Pfaff, N.Y.C./B.Q.E (installation detail), 1987, painted steel, plastic laminates, fiberglass, wood, paint, lawn furniture, awnings, 180 inches x 420 inches x 108 inches

VWS: A lot of what gets reviewed gets noticed because it is about ideas that interest the critics. It’s not necessarily a qualitative judgment about the art. Artists who can articulate these ideas in their work often have an advantage in getting the work seen and / or written about.

JP: You’re absolutely right. It’s a very important relationship. But, sometimes you’ll see work that is so sexy and the critics only talk about the mind, or work that is so intellectual and they only talk about emotion, work that is so structured and they only talk about spontaneity. The most obvious and leading force in the work is so second nature the critics don’t really see it. The other problems they’re struggling with seem more obvious to them. Whatever you think you can’t do always seems more important.

VWS: How important are mentors?

JP: I like that system. Al Held is my teacher; he’s also my very good friend. There’s a lot I owe to him. I got attention early on by people recommending me and speaking for me. I’m pretty loud and not that shy but I’m not going to say to people, “Come to my studio, it’s terrific.”

VWS: Someone in a teaching position can do a lot to help, young artists.

JP: That’s true. But, when you are 20, your ideas are 20. It’s very seldom that you can recognize that at the time. It’s particularly hard for a young teacher. I recently found some drawings from undergraduate school that I remembered as being pretty good; now they look so lame and so sweet. I found some from Yale that I thought were so sophisticated then and they are so bad. Students now are so sophisticated. They are young but don’t show their youngness. I don’t know where their work comes from emotionally. There is a tremendous amount of talent. Maybe it’s because they have so much information.

Students want me to say, “Change this, do this, read this, and your work will get better.” I can’t say that, because it’s usually something personal that is getting in their way. The real questions are things like “Why don’t you leave home?” or “Why are you camouflaging everything you know?” “Why are you being so fragile?” Their response is, “Leave me alone on that. Tell me to change the red to green.” What was good about Al Held was that he liked getting in and being very straightforward where most people back off.

VWS: A part from the kind of critical response you get, do you feel like a success as an artist?

JP: Yeah, I really do. I can draw now. I’ve done a lot of variations— big, tiny, fragile; a lot of paintings, some very intimate, some so structured, so Italian, so German, so Japanese. Something is developing and changing and it doesn’t dead-end. I’ve done a lot of leg work, I’ve read the books and done the homework, and it’s still interesting. My mom’s proud, I’m happy.

VWS: Did you ever want to do anything besides be an artist?

JP: It’s something that’s been with me since I was a child. My brother was so smart and so verbal. He is a lawyer and lives happily ever after with five children. I thought, he’s got the language, I want the language. I tried to get the language at 16, when I married a philosopher. We’re divorced. I’m so frightened of language, even postcards. I can’t write them.

When I was younger I wanted to be an architect for zoos. You know the polar bears don’t believe those little structures made for them, and I don’t think the ostrichs like those little stainless steel drinking dishes. I went to Washington University in St. Louis, where there is a great zoo built during the World’s Fair. I thought, as good as this is, we could make this better. So I was going to be radical in the animal habitat field.

But there was never really any question, never any “what if…” Things that are hard for some artists came very easy to me. I have really good eye to hand co-ordination.

VWS: What do you think are the limitations of installation work?

JP: Money is a big problem. Permission to do it is amazingly difficult to get at this point. Do you think that any museum in the country wants you to come in? My installations were not conceived on the drawing board.

The museum was the studio. But museums can’t say in advance, “this is going to be a terrific show,” they don’t know what to expect. Museums are not structured to have anything that isn’t scheduled.

VWS: Do you get a lot of commissions?

JP: Very few. In New York now there are the power collectors. Holly Solomon has a specific number of people that buy from her and most of them are involved with beautiful and luxurious objects that hang very easily on the walls. No installations exist except the ones I’ve been making during the last three years. There is one in someone’s house. The last show I did was a critical success and things did sell from it. The prices now are astronomical but there are few sales. In the last few years I’ve bought VCR’s, a new truck, and a floor in a building.

VWS: Turning yuppie?

JP: Absolutely. But you should see where the building is.

Judy Pfaff, N.Y.C./B.Q.E, 1987, painted steel, plastic laminates, fiberglass, wood, paint, lawn furniture, awnings, 180 inches x 420 inches x 108 inches

Judy Pfaff, N.Y.C./B.Q.E (installation detail), 1987, painted steel, plastic laminates, fiberglass, wood, paint, lawn furniture, awnings, 180 inches x 420 inches x 108 inches

Virginia Warren Smith was an Atlanta artist and was Managing Editor of Art Papers.