Interview with Andres Serrano

Andres Serrano, Semen and Blood II, 1990, [© Andres Serrano, courtesy de l’artiste et de la Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Bruxelles]

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS September/October 1990, Vol. 14, issue 5

The following interview was arranged for Art Papers by the Twentieth Century Art Society of the High Museum of Art.

Christian Walker: Lucy Lippard has quoted you as saying your work derives from your unresolved feelings toward Catholicism. Can you talk about these feelings and how that is manifest in your work?

Andres Serrano: I’m drawn to the aesthetics of the Church and also to identify with Christ and what he stood for. But at the same time I don’t like the direction the Church is heading in. Actually the Church has always been pretty oppressive, as far as dealing with women, blacks, minorities, gays, lesbians, and anyone else who doesn’t go along with their program. So I’m drawn to Catholicism, or Christianity, but I have great difficulty with the Church itself.

Walker: I was an altar boy, and my cousin is a priest. That imagery shows up in my own work a lot.

Serrano: It’s not a conscious decision on your part, I’m sure. It’s something that is so inbred that you can’t get away from it.

Walker: Your imagery also seems to be a stance of resistance to the culture as well as religion—a political resistance.

Serrano: I wouldn’t define it too clearly (I don’t mind if you do). But, yeah, there’s this ambiguity in the work.

Walker: You’d see it as ambiguity as opposed to cultural resistance?

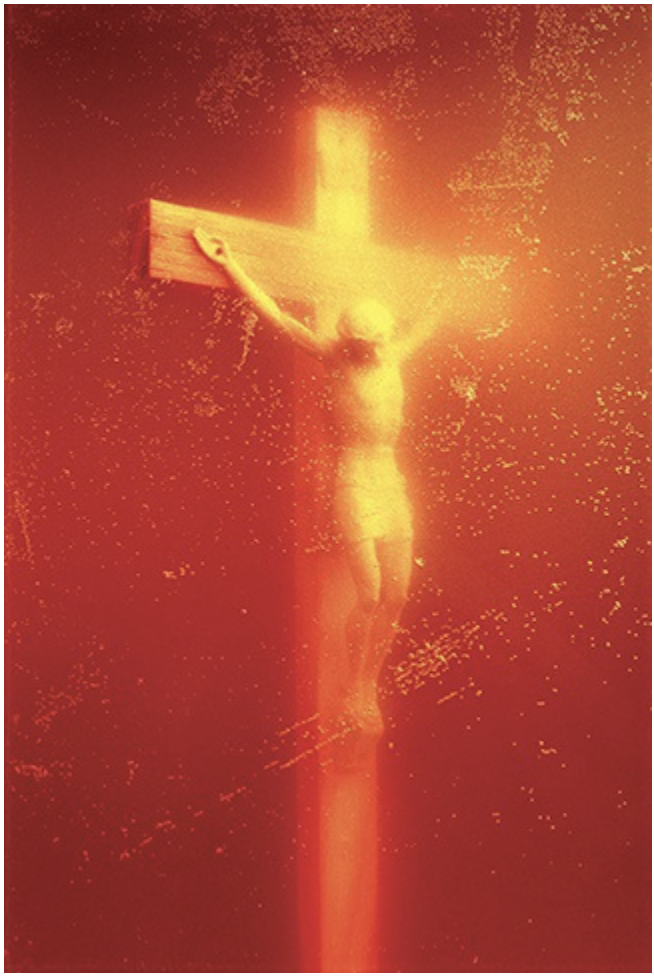

Andres Serrano, Piss Christ, 1987 [© Andres Serrano, courtesy de l’artiste et de la Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Bruxelles]

Serrano: Yeah, because I’ve never considered myself an activist, a champion of any sort in the social realm. I like to think in terms of raising more questions than answers.

Walker: What do you think about all the political references put on top of your work? There seems to be a strong political interpretation of your work both from the right and the left.

Serrano: I can’t really fight that or complain about it because the work is meant to be open to interpretation, as I always say it is. I have to take it both ways, the good with the bad.

Walker: Do you see a political interpretation as bad?

Serrano: When the right uses the work to further their own agendas and completely distort what I’m trying to do, of course I see it as a gross misinterpretation of the work. But at the same time, I realize that perhaps part of the strength of the work is that it can be used that way, both ways. It’s very satisfying as an artist when work can be accessible to more than just an art audience, can go from one arena to another.

Walker: Is that why you chose photography on some level, as being a more accessible medium?

Serrano: It certainly is more accessible for me and for my audience. I always think of myself as the artist and the audience, so that if it makes sense to me, if it strikes a chord in me, then I think and I hope that it will in others too.

Walker: Lippard has also said that your work is part of the polymorphous discourse that scholars have been calling for. Is multiculturalism a large theme for you?

Serrano: Not consciously, but I’m sure it’s there, because I have a large multicultural aspect to me.

Walker: How much has your Afro-Caribbean background influenced your imagery? Did studying with Calvin Douglas, an African-American artist, influence your approach to artmaking?

Andres Serrano, Heaven and Hell, 1984 [© Andres Serrano, courtesy de l’artiste et de la Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Bruxelles]

Serrano: Specifically I can’t say it has, but these influences operate on a variety of levels. My background is what you describe and then I also have European and Americanized influences. I would say that it mostly shows itself in the fact that I have a problem with, or I resist what I perceive as, homogenized white art. That is to say non-threatening work. I think for a person of color to do any work that is in some way threatening to a lot of people is indicative of where his roots are. The work of an artist like David Hammons doesn’t have to be specifically black in order to be uncomfortable for a lot of people.

Walker: I see Hammons’ work as being particularly Afrocentric, very much from the streets, very much from the culture of urbanized African-American people.

Serrano: I guess what I’m trying to say is that with some of his work, if you don’t know the artist you don’t necessarily think this is a black artist. You just know that it makes you uncomfortable but you don’t quite know why.

Walker: Can you talk about your first run-in with censorship, with the stigmata piece? Did that affect the work that you made from that point?

Serrano: Lucy Lippard asked my wife (Julie Ault) and me to do a window at Printed Matter in 1984. We put two photographs in the window. Then someone on the block complained about the nude female figure with the stigmata. The figure next to it is a male nude who is carrying an animal carcass. She objected to the female figure. Lucy decided to turn the images around. We put a statement up saying why, and that was it. I did think about that. But the small incidents of censorship early on were insignificant. If the Piss Christ controversy hadn’t taken place, I would never have given those instances a second thought.

I had another piece called Heaven and Hell which showed a figure of a woman, naked from the waist up, hanging next to a man (Leon Golub) in a cardinal’s suit. That piece was at a show at White Columns which at that time was in a Port Authority building and they got several complaints from several people who thought it was a Port Authority presentation. The gallery put up a disclaimer saying this was not a Port Authority presentation and had nothing to do with the Port Authority. That seemed to make people feel much better. Then there was another instance where a lab that printed my work, after they printed the stigmata picture, told me they couldn’t print my work anymore.

Walker: Heaven and Hell deals with an image of a battered and bloody woman. Lippard talks about the overt sexuality and questions its possibly being a negative representation of women. How do you feel about the representation of women in your work, about the larger issues of eroticism in your work?

Serrano: I’ve not represented women a whole lot in my photographs, especially not from a sexual aspect. In that photograph I’m referring to the relationship the Church has with women, whether they are aware of women as human beings or just take them for granted and dismiss them. The cardinal in fact seems quite oblivious to the woman’s suffering.

Walker: So you feel that’s an image of a suffering woman, as opposed to an erotic image even though the woman is voluptuous and her head is back. There is a strong erotic subtext to much of your work.

Serrano: I never thought of it as far as that picture was concerned. Then my friends would see it and say “she has nice breasts.” I never saw it that way. I’ve been looking at pornography since I was a kid, but to me that was not an erotic pose.

Walker: I think of my own work as anti-pornographic, although some of the work is an interracial interpretation of sexuality. Then someone says, Oh, they’re stag pictures, and that was a real shock to me. You really play off a lot of notions of masculinity and power, too.

Serrano: Sometimes it’s hard to be politically correct and also be true to your own instincts, as far as sexuality is concerned.

Andres Serrano, Semen and Blood II, 1990, [© Andres Serrano, courtesy de l’artiste et de la Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Bruxelles]

Walker: In your new work you use semen and menstrual blood, which at some level has homoerotic connotations. A friend of mine mentioned that the “come shot” is a very homoerotic device. It moves sex from procreation to pleasure.

Serrano: The come shots for me are autoerotic as opposed to homoerotic. The only possible reference to homoeroticism I think is that in the age of AIDS, male sexuality is thought of in homosexual terms.

Walker: What do you think of using menstrual blood, in terms of its being a powerful feminist image of the ’70s and ’80s?

Serrano: I didn’t think of it in terms of reclaiming that territory as a man, although Lippard kind of hinted at that. I thought of it more in terms of balancing the pictures about male sexuality and male reproduction with pictures about female reproduction, and bringing up the question of female reproduction rights. A lot of people have more problems with those pictures than they do with the come shots, which are very aestheticized, beautiful, unthreatening to them. In a way they’re also horizontal and passive. The other pictures are vertical and much more aggressive, and question the whole notion of masculine and feminine. It makes people feel uncomfortable sometimes because of the whole notion of wanting to look at women and not wanting to look at women, not wanting to take them seriously enough.

Walker: So there is a certain feminist analysis?

Serrano: A little bit. I would never claim to be politically correct, but I’m learning. Over the years, my wife and women friends have taught me that I have a lot to learn about male-female relationships.

Walker: Does your wife have a large influence on your work? Do you still collaborate with her?

Serrano: She’s been my biggest supporter. We don’t really collaborate. I’ll show her a photograph or tell her an idea and she’ll give me the nod or no. Now she gives me a lot more nods than she used to.

Walker: The whole notion of body fluids in your work seems to be about the age of AIDS, but also about the primitive, alchemy, and healing and ritual ceremony.

Serrano: All that stuff is traditionally more important to the non-white artist than the white artist. I try to personalize the work, and that’s why I draw on these things. My work is not terribly intellectual or theoretical. I want it to be accessible, to be personal, and at the same time I hope it strikes a universal chord.

Walker: But it’s very, very intelligent work, too. There’s a large intellectual component.

Serrano: I’m not one of those artists concerned with theory and strategy.

Walker: But it’s all there in the work. Your work was the most intriguing work in the “Ten Hispanic Photographers” show. Most of the work was fairly transparent. I thought that your work in the show was not particularly Hispanic: you were dealing with more universal things, with primitivism, with Africanism, religion—things that are important to minorities in the larger culture.

Serrano: If I have anything to be proud of as an artist, it’s the fact that I am a Hispanic person who’s not thought of as a Hispanic artist, necessarily. I’ve been in very few Hispanic shows, and I don’t mind being in them, and I don’t mind not being in them. I think it’s important for artists of color to be aware that there’s a tendency, if you let society do it to you, to segregate you and ghettoize you. It’s important not to be lost in the shuffle.

Walker: Benny Andrews talks about that in terms of his own work. If you’re a black artist in America you get called every February, Black History Month, to exhibit. There seems to be some influence in your work from the West African influence on Catholicism.

Serrano: Catholicism in this country means one thing and in Europe it means another thing and in Latin America and the Caribbean it means something else—and it’s still Catholicism. Catholicism takes many forms and has many colors.

Walker: Your work also fits in the whole discourse of postmodernism, the discussion of media and representation, your references to Western art and classical European art. How much is your work influenced by all that?

Serrano: I don’t take part in those discussions but I’m glad to be part of the discourse.

Walker: How has Western art influenced your work? There seems to be a tension between abstraction and narrative in your work, for example.

Serrano: Marcel Duchamp influenced me as he did the whole world. Abstraction has influenced me, and people like Luis Buñuel. The dada and surrealist idea of juxtaposing the strange with the normal, the mundane with the monumental.

Walker: There is also an element of classical composition in your work.

Serrano: I think composition is very important. In art school I started in painting and sculpture and that gave me a feel for composition. You have to be able to successfully translate an idea in a visually effective manner, so you have to have exciting composition.

Walker: Your work is very internal, it’s not at all in the documentary tradition of photography.

Serrano: My early work was street portraits. But sometime around ’83 I decided I wanted to become a tableau photographer. I wanted to take the pictures in my head rather than pictures that I found out there.

Edward S. Curtis, Shows As He Goes, 1905, photographic print, 16.75 x 12 inches [courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington D.C.]

Edward S. Curtis, Three Horses, 1905, photographic print [courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington D.C.]

Walker: What photographers were you inspired by?

Serrano: One of my all time favorite photographers has been Julia Margaret Cameron. I think her portraits are extremely strong. Some people saw her as an amateur; she didn’t have the right equipment, her pictures weren’t crystal clear. But as far as I’m concerned, she took some of the best photographs ever taken. The reason I feel an affinity with her is that as a photographer, I’m not that interested in the technical aspects of photography. For years I used the same lights and camera and I never learned to print. I think I’m more an artist with a camera than a real photographer. I would say that sometimes I’m anti-photography.

Walker: Cameron’s work deals with allegory and the transcendental state and mysticism. All of which your work deals with.

Serrano: But some of the portraits are so direct, that you get beyond all that and you just see them as beautiful portraits. Another person I’ve always liked is Edward Curtis. I never realized that Curtis was controversial…

Walker: For his portrayal of Native Americans. How did you manage to stay out of that political discourse on someone who made work that was so charged?

Serrano: I guess mostly by concentrating on the work. I’ve just completed a new series that refers to the portraits he did of American Indians. I went around with a friend who helped me carry my equipment, including a photographic background, a battery operated lighting system, an umbrella, a tripod. I went around and found homeless people in the subways, in the street, in the parks. I even found people looking through garbage. I was looking for the hard core homeless that sometimes even the homeless don’t want to talk to. We set them up in subways in situations and took their portraits, studio portraits. I was not in a position to take the homeless to a studio so I took the studio to the homeless. Basically, I gave them a fee to pose for me for 15 minutes, and had them sign model releases. When the whole Piss Christ controversy erupted, I said that I didn’t have a problem with disturbing work, provocative work. I said that in fact I looked forward to the day when I could take pictures that were disturbing to me. That’s why I took these pictures, to explore the nature of that discomfort, to be able to look at that fine line we walk between exploration and exploitation.

Walker: When you start doing work like that people confuse it with documentary. Avedon ran into that with his pictures of the West.

Serrano: Curtis’ portraits are documentation, but I also think that they’re more than documentation.

Walker: They have a romantic, Westernized notion of Native Americans.

Serrano: Right. Which I find refreshing, compared to Hollywood’s version of events and portrayal of American Indians. Basically those are the only two reference points I have for American Indians-Westerns that I grew up with in the ’50s and ’60s, and the pictures of Curtis.

Walker: How do you see the new pictures of yours fitting into that?

Serrano: I see these pictures as being also about marginality and invisibility. On a personal level it was very satisfying to relate to people one to one that I would never have looked at under different circumstances. People who are sometimes quite abnormal by our standards, except that for 15 or 20 minutes we had a traditional photographer-model relationship. I took pictures of one woman who I’m sure was a crackhead. She had problems focusing her eyes. Her head and eyes darted very quickly. But she’s one of my favorite portraits. She’s beautiful.

Walker: That brings up contradictions, like the idea that the work could be romanticized because it becomes very beautiful.

Serrano: That’s the whole point. Why should the homeless be looked at only in a certain way? I think you’re talking about a certain prejudice if we think these pictures are bad because the homeless aren’t being portrayed like they really are. What does that mean? These pictures are more collaborations with the subjects than documentations or fictionalizations. Who says the homeless can’t have studio portraits like everyone else?

Andres Serrano, Kirk, 1990, [© Andres Serrano, courtesy de l’artiste et de la Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Bruxelles]

Andres Serrano, Darlene, 1990, [© Andres Serrano, courtesy de l’artiste et de la Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Bruxelles]

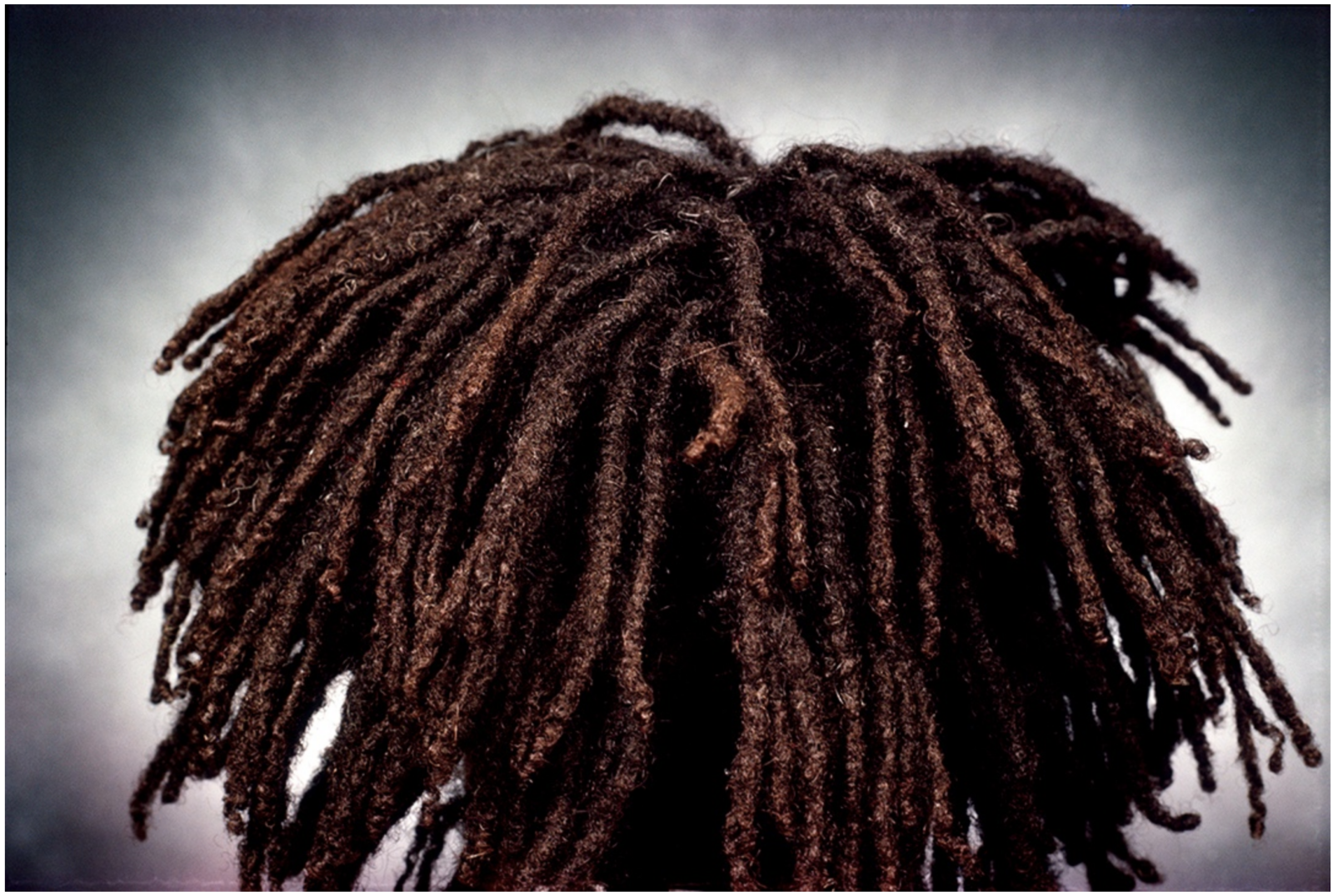

Walker: Your picture Dread seems to have some of that kind of energy to me that seems like a picture of resistance; it makes me think of Public Enemy’s album Fear of a Black Planet. It seems like one of your most political images.

Serrano: I guess it would be. I’ve always identified with the music of the streets, specifically hip-hop. As far as I’m concerned it’s better to have anarchy in the clubs than real revolution in the streets. I don’t see why people feel so threatened by the music. Maybe they don’t want to remember that at one time young people were more militant than they are now. They weren’t just making music, they were planning revolutions.

Walker: And soon will be again.

Serrano: If the trend continues.

Walker: You have a series called “The Blacks”; could you talk about them?

Serrano: It was an unsuccessful series for me, but it was a necessary step for me. It led me to the “nomads” pictures which is what the Curtis-inspired work is about.

Walker: What were you going after when you were doing the series, why was it unsuccessful for you?

Andres Serrano, Dread, 1987, [© Andres Serrano, courtesy de l’artiste et de la Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Bruxelles]

Serrano: It was difficult for me to do technically; I didn’t have the right lighting equipment. Maybe I’ll redo it, but I’ve kind of lost interest. But there were a couple of shots that were very good.

Walker: I was interested in the reference to the Genet work, that sets up a supreme white culture and a black culture that imitates it and, in control, becomes the white culture. It’s an unbelievably pessimistic view of revolution, change, or progression. It mirrors the ’80s, the emergence of minorities, but the class structure is getting much more divided, or much poorer.

Serrano: And angrier on both sides.

Walker: What I found interesting about the controversy is Dread Scott is a black man, you’re identified as a Hispanic artist, Mapplethorpe is a gay artist. There seemed to be a notion that third world people and people who were outside mainstream culture are also activists. I question that if the terms were different, if it had been a white male heterosexual artist doing the work (although he wouldn’t have been doing work like this anyway), it would have been different. How do you feel about your work being resistant to culture?

Serrano: I think I’m in good company with those guys.

Christian Walker was an Atlanta-based artist and critic.