Interview with Mary Ellen Mark

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS May/June 1992, Vol. 16, issue 3.

Mary Ellen Mark exhibited recent work at Fay Gold Gallery in Atlanta April 10 – May 6. Art Papers wishes to thank the gallery for its assistance in arranging this interview.

Christian Walker: Notions about documentary have changed a lot over the past twenty years. How do you feel about that?

Mary Ellen Mark: It’s definitely the case with documentary still photography. There’s very little chance to do the kind of long documentary projects that are sponsored by magazines. They’re much more interested in commercial, slick imagery. But I think that what you have to do—I’ve been working for over 2.5 years as a magazine photographer, so I’ve seen this change, and magazines are really the way that I finance my work—is sort of bend with it, but not become something other than what you are. I used to work a lot for Life, but in the past year and a half I’ve been working more for Vogue, and actually they’ve allowed me to do pieces that I love to do. I did a piece for them on the Special Olympics last year, and I did a series of portraits of young Olympic athletes; I love doing portraiture, and they’ve actually been very supportive and great to work for.

Walker: How do you go about choosing your subject matter?

Mark: Those were projects that they chose for me, but as far as the real documentary work, I’m trying to find other ways of sponsoring my own work—even, if necessary, trying to convince advertising agencies to let me do really strong documentary work, but to use it in advertising. Or grants—I’m willing to go in that direction. I think we have to face it—the old days when you’d get a call from Life magazine to work for two months on a documentary project don’t exist anymore, for many different reasons. These projects cost a lot of money, and the magazines don’t have the financial backing to go and do them. They take much more time and cost a lot more than doing portraits. I’m never going to give up doing the kind of work that I love—I just need to find other ways to do it and convince other people to allow me to do it.

Walker: What about the current critical stance about documentary being a class-biased genre, or photographing the Other, the exotic?

Mark: You know what really pisses me off a lot? When I do documentary work, often I photograph people living on the fringes of society, because they’re the people who really interest me. Maybe part of it is selfish because I feel that their lives are worth looking at and they’re really interesting to look at; I also think that photography gives you a kind of immortality, and I’d rather give that immortality to people who normally wouldn’t have it. I hate it when people say, “Isn’t it exploitative to photograph people who are less advantaged?” Why isn’t it exploitative to photograph film stars? What’s the difference? Why shouldn’t everyone have a voice? Why shouldn’t everyone be seen? I wouldn’t want to photograph these people without giving them a sense of being noble. It’s one thing if you photograph people to make fun of them—and that goes for photographing celebrities, too. I don’t like that kind of photography. I would prefer to photograph the people that I care about.

I’ve done a couple things in the past, like my work on the Aryan Nation in Haven Lake, Idaho—those were terrible people and in a way that bored me. It was sort of exotic, because they’re so weird. But when you photograph them, you have to sort of condemn them, because they’re people that you don’t love and respect. I find that less interesting than photographing people I really care about, and I really care about the disadvantaged. Their lives fascinate me. Their passion fascinates me.

Walker: What do you think about moving outside the context of your books to the gallery wall?

Mark: Why not? What’s the difference? Why should only a celebrity be on a gallery wall? Why can’t a great picture of whatever or whoever be on a gallery wall? It’s people’s own hang-ups that force that kind of distinction.

Walker: It comes, I think, from a lot of postmodernist criticism in the ‘80s, like Martha Rosler’s pieces on documentary.

Mark: I guess the people who think it’s exploitative have never had the experience themselves. They’ve never gotten to know the people. It’s easy to point fingers and condemn.

Walker: There’s an intimacy about your images.

Mark: I love to be around people’s lives. To have access to real lives makes me the happiest.

Walker: How did you make the shift tot platinum prints?

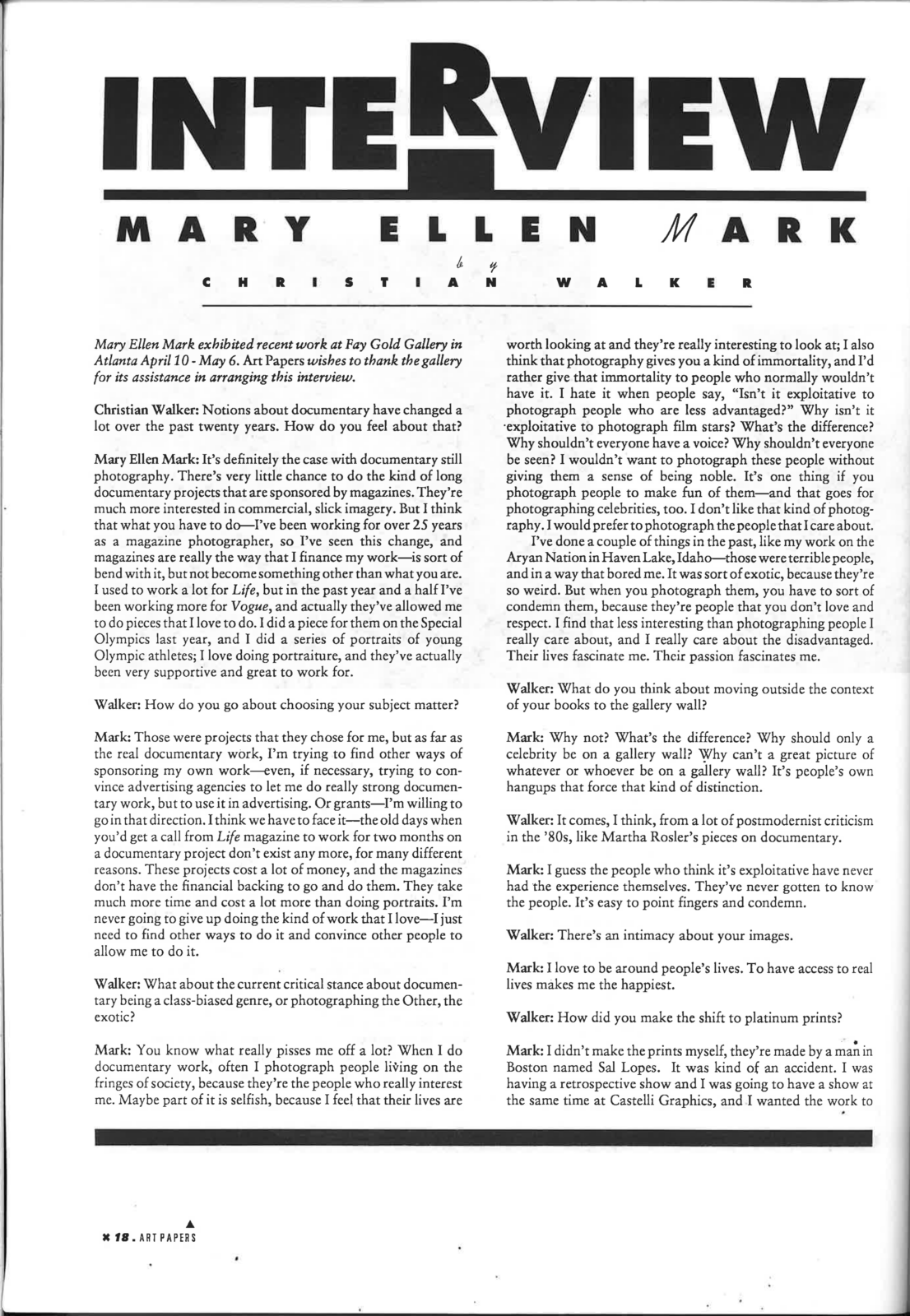

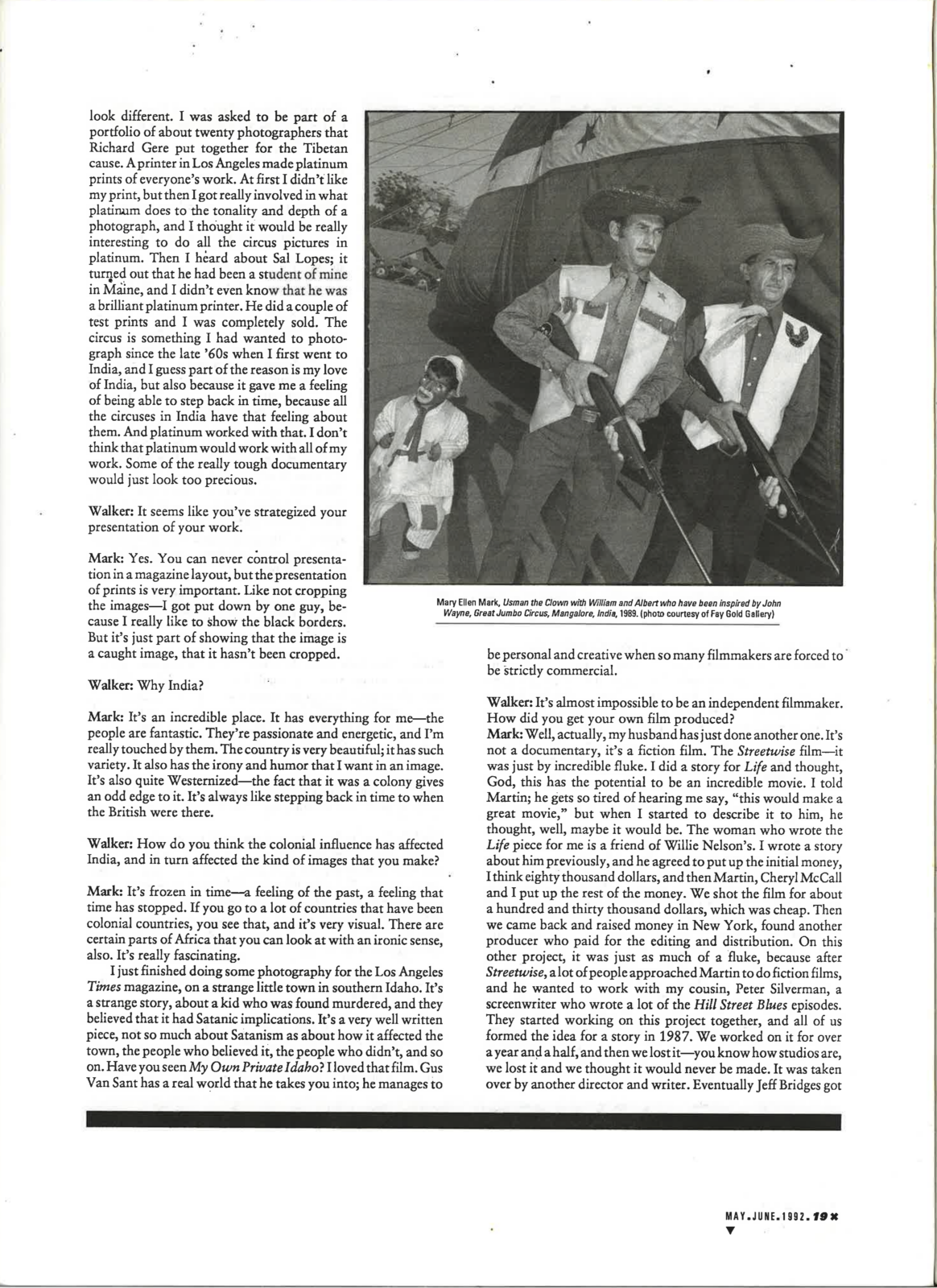

Mark: I didn’t make the prints myself, they’re made by a man in Boston named Sal Lopes. It was kind of an accident. I was having a retrospective show, and I was going to have a show at the same time at Castelli Graphics, and I wanted the work to look different. I was asked to be part of a portfolio of about twenty photographers that Richard Gere put together for the Tibetan cause. A printer in Los Angeles made platinum prints of everyone’s work. At first I didn’t like my print, but then I go really involved in what platinum does to the tonality and depth of a photograph, and I thought it would be really interesting to do all the circus pictures in platinum. Then I heard about Sal Lopes; it turned out that he had been a student of mine in Maine, and I didn’t even know that he was a brilliant platinum printer. He did a couple of test prints, and I was completely sold. The circus is something I had wanted to photograph since the late ’60s when I first went to India, and I guess part of the reason is my love of India, but also because it gave me a feeling of being able to step back in time, because all the circuses in India have that feeling about them. And platinum worked with that. I don’t think that platinum would work with all of my work. Some of the really tough documentary would just look too precious.

Walker: It seems like you’ve strategized your presentation of your work.

Mark: Yes, You can never control presentation in a magazine layout, but the presentation of prints is very important. Like not cropping the images—I got put down by one guy, because I really like to show the black borders. But it’s just part of showing that the image is a caught image, that it hasn’t been cropped.

Walker: Why India?

Mark: It’s an incredible place. It has everything for me—the people are fantastic. They’re passionate and energetic, and I’m really touched by them. The country is very beautiful; it has such variety. It also has the irony and humor that I want in an image. It’s also quite Westernized—the fact that it was a colony gives an odd edge to it. It’s always like stepping back in time to when the British were there.

Walker: How do you think the colonial influence has affected India, and in turn affected the kind of images you make?

Mark: It’s frozen in time—a feeling of the past, a feeling that time has stopped. If you go to a lot of countries that have been colonial countries, you see that, and it’s very visual. There are certain parts of Africa that you can look at with an ironic sense also. It’s really fascinating.

I just finished doing some photography for the Los Angeles Times magazine, on a strange little town in southern Idaho. It’s a strange story, about a kid who was found murdered, and they believed that it had Satanic implications. It’s a very well written piece, not so much about Satanism as about how it affected the town, the people who believed it, the people who didn’t, and so on. Have you seen My Own Private Idaho? I loved that film. Gus Van Sant has a real world that he takes you into; he manages to be personal and creative when so many filmmakers are forced to be strictly commercial.

Walker: It’s almost impossible to be an independent filmmaker. How did you get your own film produced?

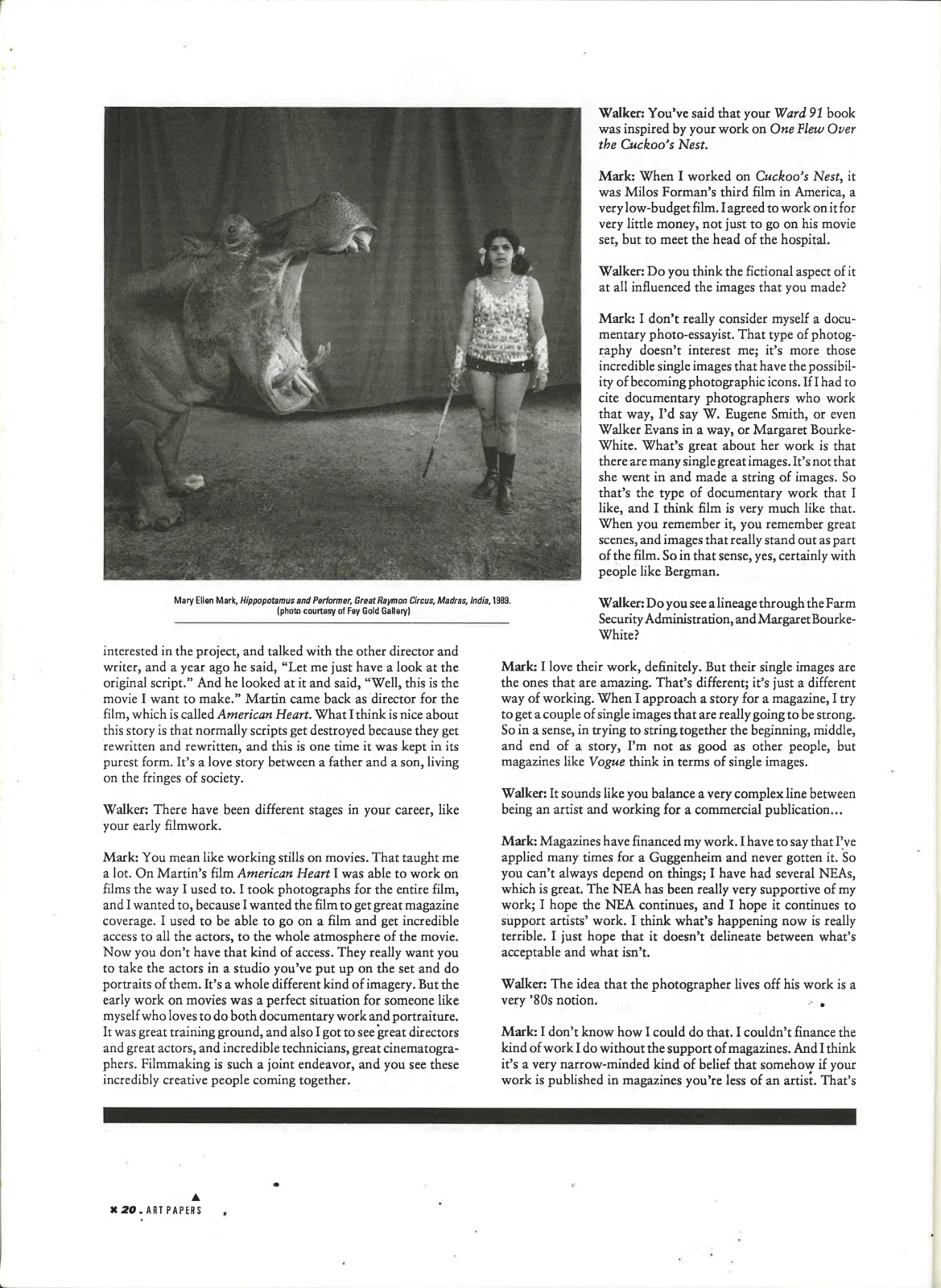

Mark: Well, actually, my husband has just done another one. It’s not a documentary, it’s a fiction film. The Streetwise film—it was just by incredible fluke. I did a story for Life and thought, God, this has the potential to be an incredible movie. I told Martin; he gets so tired of hearing me say, “this would make a great movie,” but when I started to describe it to him, he thought, well, maybe it would be. The woman who wrote the Life piece for me is a friend of Willie Nelson’s. I wrote a story about him previously, and he agreed to put up the initial money, I think eighty thousand dollars, and then Martin, Cheryl McCall and I put up the rest of the money. We shot the film for about a hundred and thirty thousand dollars, which was cheap. Then we came back and raised money in New York, found another producer who paid for the editing and distribution. On this other project, it was just as much of a fluke, because after Streetwise a lot of people approached Martin to do fiction films, and he wanted to work with my cousin, Peter Silverman, a screenwriter who wrote a lot of the Hill Street Blues episodes. They started working on this project together, and all of us formed the idea for a story in 1987. We worked on it for over a year and a half, and then we lost it—you know how studios are, we lost it and we thought it would never be made. It was taken over by another director and writer. Eventually Jeff Bridges got interested in the project and talked with the other director and writer, and a year ago he said, “Let me just have a look at the original script.” And he looked at it and said, “Well this is the movie I want to make.” Martin came back as director for the film, which is called American Heart. What I think is nice about this story is that normally scripts get destroyed because they get rewritten and rewritten, and this is one time it was kept in its purest form. It’s a love story between a father and a son, living on the fringes of society.

Walker: There have been different stages in your career, like your early film work.

Mark: You mean like working stills on movies. That taught me a lot. On Martin’s film American Heart I was able to work on films the way I used to. I took photographs for the entire film, and I wanted to because I wanted the film to get great magazine coverage. I used to be able to go on a film and get incredible access to all the actors, to the whole atmosphere of the movie. Now you don’t have that kind of access. They really want you to take the actors in a studio you’ve put up on the set and do portraits of them. It’s a whole different kind of imagery. But the early work on movies was a perfect situation for someone like myself who loves to do both documentary work and portraiture. It was great training ground, and also I got to see great directors and great actors, and incredible technicians, great cinematographers. Filmmaking is such a joint endeavor, and you see these incredibly creative people coming together.

Walker: You’ve said that your Ward 91 book was inspired by your work on One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Mark: When I worked on Cuckoo’s Nest, it was Milos Forman’s third film in America, a very low-budget film. I agreed to work on it for very little money, not just to go on his movie set, but to meet the head of the hospital.

Walker: Do you think the fictional aspect of it at all influenced the images that you made?

Mark: I don’t really consider myself a documentary photo-essayist. That type of photography doesn’t interest me; it’s more those incredible single images that have the possibility of becoming photographic icons. If I had to cite documentary photographers who work that way, I’d say W. Eugene Smith, or even Walker Evans in a way, or Margaret Bourke-White. What’s great about her work is that there are many single great images. It’s not that she went in and made a string of images. So that’s the type of documentary work that I like, and I think film is very much like that. When you remember it, you remember great scenes, and images that really stand out as part of the film. So in that sense, yes, certainly with people like Bergman.

Walker: Do you see a lineage through the Farm Security Administration, and Margaret Bourke-White?

Mark: I love their work, definitely. But their single images are the ones that are amazing. That’s different; it’s just a different way of working. When I approach a story for a magazine, I try to get a couple of single images that are really going to be strong. So in a sense, in trying to string together the beginning, middle, and end of a story, I’m not as good as other people, but magazines like Vogue think in terms of single images.

Walker: It sounds like you balance a very complex line between being an artist and working for a commercial publication…

Mark: Magazines have financed my work. I have to say that I’ve applied many times for a Guggenheim and never gotten it. So you can’t always depend on things; I have had several NEAs, which is great. The NEA has been really very supportive of my work; I hope the NEA continues, and I hope it continues to support artists’ work. I think what’s happening now is really terrible. I just hope that it doesn’t delineate between what’s acceptable and what isn’t.

Walker: The idea that the photographer lives off his work is a very ‘80s notion.

Mark: I don’t know how I could do that. I couldn’t finance the kind of work I do without the support of magazines. And I think it’s a very narrow-minded kind of belief that somehow fi your work is published in magazines you’re less of an artist. That’s bullshit. What’s important is the work be strong and good. And to find positive support for it. I think it’s more difficult for young documentary magazine photographers, simply because there’s not that kind of financing around now. But I think it should make you fight harder to do your work.

Walker: Do you see documentary becoming more critical in terms of its analysis? For example, the idea of African-American photographers creating works the deal with African-American culture.

Mark: I think that’s important, don’t you? The more passionate work that exists, the better it is for everybody. I know how inspiring it is for young photographers. I’m disappointed now that I can’t pick up magazines and see tons and tons of great documentary work, because it was very inspiring to see it. I hope that’ll change.

Walker: Do you feel your experience has been different as a woman in a genre that is very male-dominated?

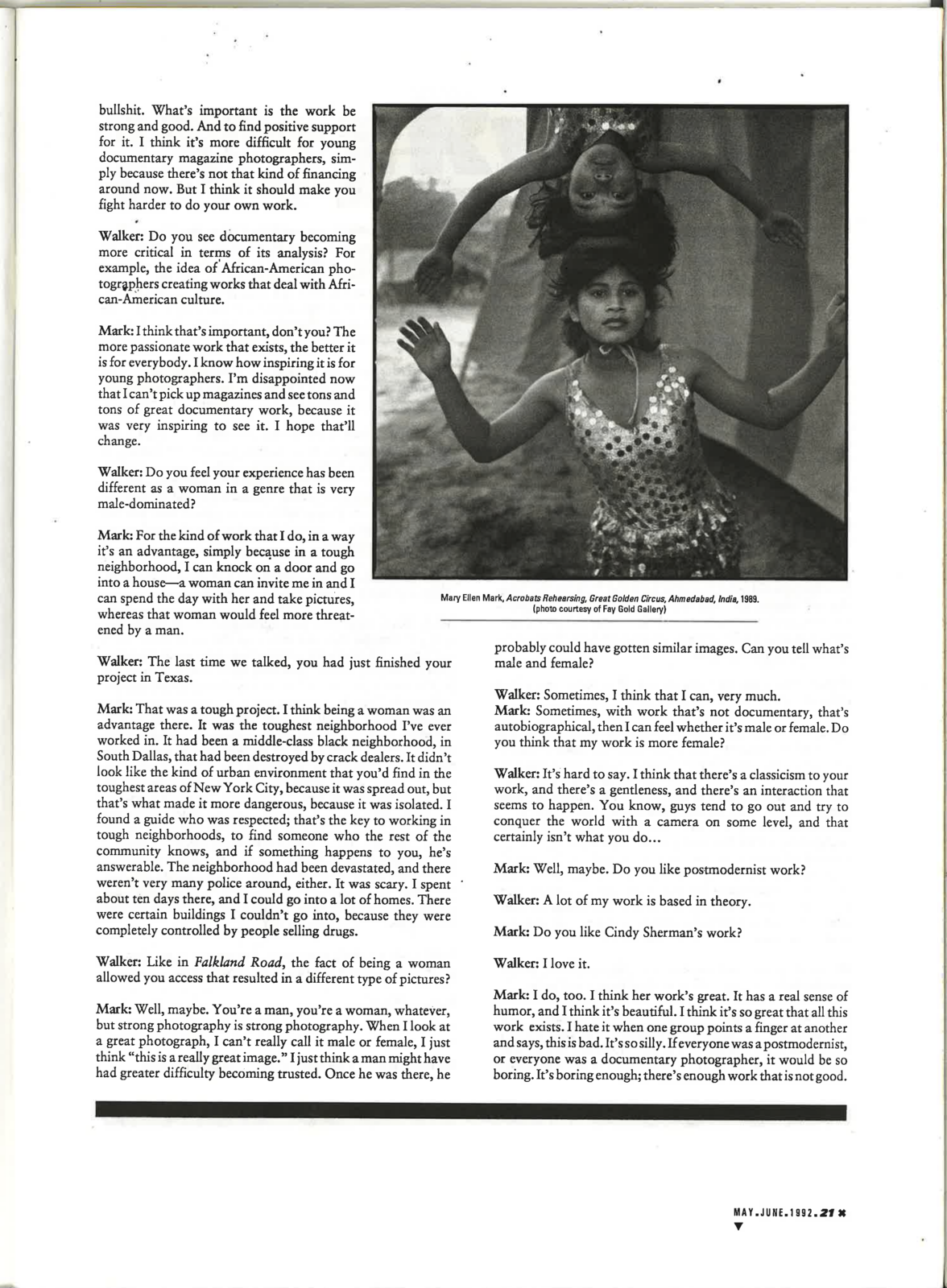

Mark: For the kind of work that I do, in a way it’s an advantage, simply because in a tough neighborhood, I can knock on a door and go into a house—a woman can invite me in and I can spend the day with her and take pictures, whereas that woman would feel more threatened by a man.

Walker: The last time we talked, you had just finished your project in Texas.

Mark: That was a rough project. I think being a woman was an advantage there. It was the toughest neighborhood I’ve ever worked in. it had been a middle-class black neighborhood, in South Dallas, that had been destroyed by crack dealers. It didn’t look like the kind of urban environment that you’d find in the toughest areas of New York City, because it was spread out, but that’s what made it more dangerous, because it was isolated. I found a guide who was respected; that’s the key to working in tough neighborhoods, to find someone who the rest of the community knows, and if something happens to you, he’s answerable. The neighborhood had been devastated, and there weren’t very many police around either. It was scary. I spent about ten days there, and I could go into a lot of homes. There were certain buildings I couldn’t go into, because they were completely controlled by people selling drugs.

Walker: Like in Falkland Road, the fact of being a woman allowed you access that resulted in a different type of pictures?

Mark: Well, maybe. You’re a man, you’re a woman, whatever, but strong photography is strong photography. When I look at a great photograph, I can’t really call it male or female, I just think “this is a really great image.” I just think a man might have had a greater difficulty becoming trusted. Once he was there, he probably could have gotten similar images. Can you tell what’s male and female?

Walker: Sometimes, I think that I can, very much.

Mark: Sometimes, with work that’s not documentary, that’s autobiographical, then I can feel whether it’s male or female. Do you think that my work is more female?

Walker: It’s hard to say. I think that there’s a classicism to your work, and there’s a gentleness, and there’s an interaction that seems to happen. You know, guys tend to go out and try to conquer the world with a camera on some level, and that certainly isn’t what you do…

Mark: Well, maybe. Do you like postmodernist work?

Walker: A lot of my work is based in theory.

Mark: Do you like Cindy Sherman’s work?

Walker: I love it.

Mark: I do, too. I think her work’s great. It has a real sense of humor, and I think it’s beautiful. I think it’s so great that all this work exists. I hate it when one group points a finger at another and says, this is bad. It’s so silly. If everyone was a postmodernist, or everyone was a documentary photographer, it would be so boring. It’s boring enough; there’s enough work that is not good.

Walker: Have you ever done any work that didn’t reflect your personal or political views?

Mark: I don’t really think of myself as political. I think that political photographers are the ones who photograph wars and so on; if it’s political, it’s because I’m definitely for the underdog. In general, I’m for people who have had less of a chance; I just am, I can’t help that. So I hope that my pictures say something about that. But I’ve never really gone out and said, I’m a feminist and I’m doing this or that. Although I believe in women being free and powerful and strong and all that, I’ve never actually directed my work in that way. I always tell students that from the very moment I begin to work, I have a camera around my neck, and it’s always clear why I’m there. Because if you begin to draw up this friendship with someone, and then you suddenly pull out a camera, there’s something very hypocritical about that.

Walker: You assert your identity from the start.

Mark: I’m the photographer, and they’re the people being photographed. That really becomes clear. Beyond that, a friendship develops, or some kind of a relationship develops.

Walker: What are you working on now?

Mark: I’m actually just working on America right now, just taking pictures around this country. I’m also working with my husband, as kind of producer with him, on the films he’s working on. We’re trying to put together a film in India, with a John Rivingwood script, based on the circus. I have almost enough to do it; I’d like to make another trip back there, just to round out the photographs.

Walker: You seem to move in lots of different strata and cultures.

Mark: The idea of exoticism in traveling doesn’t interest me at all. I think the country is one of the most interesting countries, just because of all the different things it touches in our common human experience. That’s what does interest me, when I do travel to places like India or Africa, to try and touch on those things that deal with common human experiences that cross cultural boundaries. It doesn’t interest me to go off to some strange tribe in New Guinea and photograph some ritual. What interests me more is to look for those threads that we can all relate to and understand, and you can find that anywhere in the world. You can certainly find that in this country. You can take a picture anywhere, and no place is more interesting than any other. I happen to love India, because it touches my soul, but images that are just exotic don’t interest me.

Walker: Documentary has an inherent ability to objectify people, to make them the Other, to make them exotic, and so on.

Mark: Sort of like the National Geographic. Many of their photographers are great photographers, but that type of storytelling doesn’t interest me. When I’m teaching I try to make students understand that I don’t want them to be illustrators. I don’t want any how-to pictures. I think that photographs, whether documentary or postmodernist or whatever, have to have something that touches the core of your soul.

Walker: So you think that there’s a universality about the human spirit?

Mark: It’s something that you look at and you can say, “Ah, I feel, I understand that.” Even when you look at the work of the great fashion photographers—like the show of early photos from Vogue—they’re fashion photographs, but they’re great photographs. You can react to a sense of really beautiful space, incredible light—all of these things hit a universal core. Do you know what I mean? It doesn’t have to be one thing or another, it just has to work.

Walker: Martha Rosler has said that photography comes from a position of privilege, and you put it on the wall to reinforce this notion of privilege. When you talk about things like fashion—

Mark: When I look at the fashion pictures that I love, I’m not even distinguishing them as fashion pictures, I’m looking at them as beautifully designed images. There are some incredible Stiechen pictures. And he was a fashion photographer. He also made some great portraits of our time, and the fact that he was a fashion photographer doesn’t make him any less important. There’s so much of classifying people—it’s such a fascist way of thinking.

Walker: I agree, but then, there’s The Family of Man exhibit, which becomes a maudlin view of the world.

Mark: Not all those pictures are great pictures; some are, some aren’t. It was also done at a time when the world was so much more naïve. There are still people doing those kinds of cliches. That’s what’s important to get away from. I had to do a project for Fortune last year on rural poverty, and it was a really difficult assignment. There’s so much poverty in this country you fall over, but you want to break the stereotypes, those cliches, because you don’t want to do them again. I was thinking when I was photographing, “This is a piece on poverty. I’m going to tell everyone I’m photographing that this is a piece on poverty, just so they know that.” Otherwise, my God, you photograph someone and suddenly they see their picture and it’s a piece on poverty—it puts you in a very odd position. What I would say wouldn’t be, I’m pointing a finger at you because you’re poor—I would tell them that it’s a piece about how people are affected by the economy, and they would say, yes, that’s true, I have no money, I’m on welfare, or whatever. But you have to be clear, because you have a responsibility, not just with the picture, but with the text.

Walker: Do you find, with twenty-five years of work, that you are becoming clearer in terms of what you want?

Mark: Definitely.

Christian Walker was an Atlanta-based artist and photographer.