Adrian Piper

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS March/April 1988, Vol. 12, issue 2.

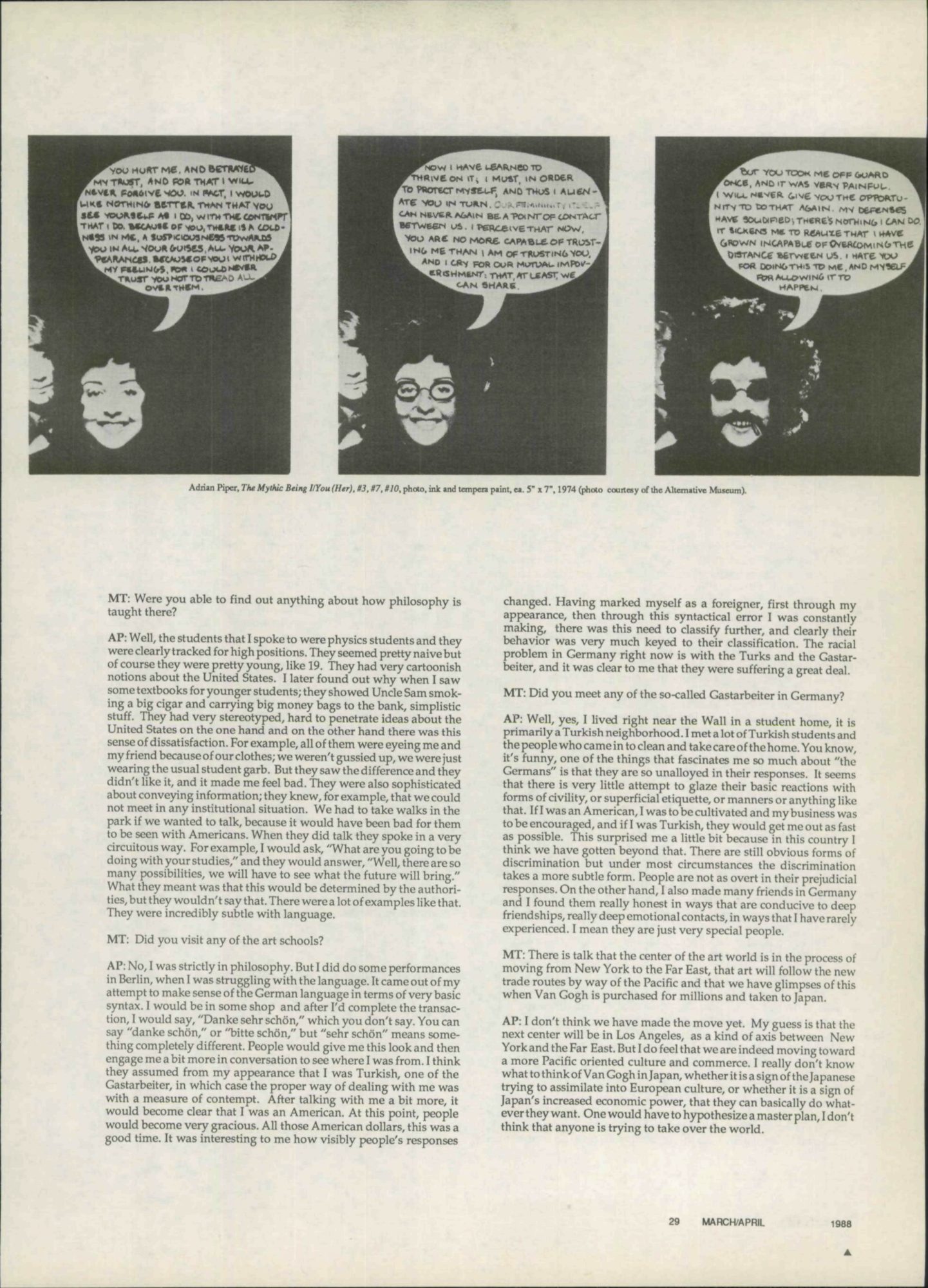

Adrian Piper was in Atlanta on November 21, where she gave a public lecture in conjunction with her exhibition at Nexus Contemporary Art Center. “Reflections, 1967-87” featured many of Piper’s earlier conceptual works, installations, video, and documentations of mixed-media performances. Themes of racial discrimination and social injustice run through most of Piper’s work. She says her current work is concerned with “the ways in which racism and the cause of discrimination affect people within themselves, and in their intersocial interactions, interpersonal relationships that they have with people with whom they presume to have a certain amount of intimacy and how simplistic stereotypes of what people are can really derail these interactions and deflect intimacy—when we interact with preconceptions of what someone is, rather than the person him or herself.” Piper has a Ph.D. in philosophy and teaches at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

Mildred Thompson: Tell me about your studies, your decision to get a Ph.D., and something too about your life in academia.

Adrian Piper: There was a lot of interest in analytical philosophy in the art world when I was a student at the School of Visual Arts. Jasper Johns was very influenced by Wittgenstein, and Joseph Kosuth was at the School of Visual Arts and getting very interested in analytical philosophy. I was doing wood sculpture; I had started showing my work pretty young, I was 19. I was asked to write something about my work for an exhibition catalogue, so I wrote this very long and confused statement about space and time and walking around objects, and forms of perception and so on. A friend of mine who was in philosophy read this and said, “Look, you gotta be joking. If you’re going to be talking about this stuff, you really have to read Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason.” So I did. And I loved it. It was just a revelation to me. Of course, I didn’t understand it, but I really thought I did. So, I decided to go back to school. I went to City College and majored in philosophy.

You know, it’s funny how things happen. At the same time I was in school studying philosophy, I was doing street performances, and I was doing conceptual art notebooks which, of course, are not particularly lucrative. I was continuing to show my work, but I had pretty much dropped out of an art market context. My studies seemed to be more of the same kind of activity and very much integrated with my thinking about art. I was pretty sure that I was never going to go into the art market in a big way, because my work just didn’t seem like the kind that anyone was going to buy. So I just kept going. I went on to graduate school and really enjoyed it; I worked very hard. So it just developed its own momentum.

MT: During this time of studying philosophy, did you find that the things you were learning were helping you to develop ideas that could be transferred to or used in your art work? Could you see any kind of relationship between your studies and your own thinking about what you were doing in the visual arts?

AP: Well, this is complicated. Yes, I did see a relationship; on the other hand, I tried not to force any artificial connections. For example, I didn’t study aesthetics in graduate school; I did social and political philosophy and epistemology. The skills helped tremendously: learning to think clearly about my own ideas and really practicing writing, just articulating some of what was going on in my work. I can’t overemphasize how extremely helpful it was to have had that training in philosophy. And then, also, my work was becoming more and more politically oriented. I was dealing with racism and racial stereotypes and found that studying social and political philosophy gave me a vocabulary within which to work as an artist. It isn’t as if I would not have found the words at all had I not been studying philosophy, but I think it would have been harder. I think it is hard for me to say in words what my work is about, because my work just does not come out of the same place as this kind of discursive, conceptual thinking.

MT: You also studied in Heidelberg. What was that experience like?

AP: Oh, that was wonderful. When I was studying at Harvard, I was working mostly in social and political philosophy, and working a lot with John Rawls, whose work I admire deeply. I think he is almost undeniably the most important philosopher of the 20th century. Since I had done a lot of work on Kant as an undergraduate, I was very Kantian in my orientation. As I was working out my own picture of what I wanted to do with my dissertation, I got very interested in Kant’s unpublished writings. I started working with Professor Dieter Heinrich, who was visiting Harvard from the University of Heidelberg; he suggested that I spend some time in Germany. So I spent a year in Heidelberg working on some translations of Kant’s work on moral philosophy and doing some of my own work. I was working on Hegel and Kant at the same time. I was not taking structured courses, but was sitting in on courses and involved in a couple of reading groups. My German improved tremendously. A great revelation for me was the discovery that, if you become fluent in another language you become a different person, because you have to express yourself slightly differently. It was very liberating for me. Among other things, when you start out in a new country and you don’t know the language, you are reduced to the level of a five-year-old. So it was like growing up through the year and being able to have more and more sophisticated conversations and relationships with people.

MT: Is it not true that, after learning a foreign language, one becomes, sometimes for the first time, really conscious of one’s own language, and that after a while one begins to speak it as if it were, too, a foreign language?

AP: Oh yes, that has really happened to me. I feel as though my command of syntax is just going to hell. I don’t conjugate verbs properly anymore; I’ve just lost it completely.

MT: Heidelberg is a very beautiful, fairytale kind of town. Did you like living there?

AP: I liked it because I had a lot of friends there, but the place I really liked was Berlin, where I spent four months in 1977.

MT: You were in Berlin in the midst of the neo-expressionist movement?

AP: Yes, but I actually didn’t see very much of that kind of work. There is a lot of political art in Berlin about superpower relationships, about the Wall, so mostly I saw that. I was there in my philosophy mode; everyone I knew was in philosophy, so I really didn’t make any contact with the arts at all.

I found Berlin fascinating because the traces of history are so vivid and so concrete. You can really see the bad consequences of decisions made by people at earlier times—like when you’re on the U-bahn, the subway in Berlin, you pass through two stations in East Berlin where the train doesn’t stop, where there are armed guards on the platform to make sure that people don’t escape. It’s really chilling. When you get on one of the trains going out to the beaches, they’re packed with old people, and it is very hard not to think about where these people were during the war, and what they are doing here now.

MT: Did seeing and experiencing the Berlin Wall bring about any emotional responses?

AP: Oh yes. It is tragic: families being divided, people being killed trying to escape, being caught hanging under cars trying to get out through the chock points. I knew the textbook stories, the history of the wars and diplomatic decisions, but it was the first time I had seen the consequences of all that, actually seeing people standing on the other side of the wall looking over at me. It was a very profound experience for me and I just haven’t gotten over it.

MT: Can you say something about the contrast of the two Berlins, East and West?

AP: West Berlin has all the rebuilding, all the ads and all the shops, and it’s busy and commercial and very much a Western city. In East Berlin you have all the monumental buildings. It is in East Berlin that you get the feeling that this was once a capital of a European nation, and yet, there are no advertisements, no cars, no signs, no shops, very few people on the streets, the people you see are dressed-it is not a question of them not being very fashionable; they are all wearing dungarees, but they aren’t made very well, and very often they are wearing plastic shoes. It’s like a very stifled version of something that was very, very grave and important.

MT: Do you think that East Berlin should be left in ruins as a kind of monument to the destructions of war?

AP: I do think that. In East Berlin you get a sense of what is left; it is a gravestone. And I think that is the way it should be to remind us.

MT: Did you see any other Eastern Bloc countries?

AP: I passed through Poland, but just on the train. I was in Moscow for a time, arranged through a friend who was studying there, and was there just ten days before the celebrations of the October Revolution. I didn’t have a special passport and had to leave after ten days.

MT: Were you able to visit the universities, meet any of the students?

AP: Yes, I did visit Moscow University and spoke to some of the students through my friend who was fluent in Russian. It was hard.

MT: Were you able to find out anything about how philosophy is taught there?

AP: Well, the students that I spoke to were physics students and they were clearly tracked for high positions. They seemed pretty naive but of course they were pretty young, like 19. They had very cartoonish notions about the United States. I later found out why when I saw some textbooks for younger students; they showed Uncle Sam smoking a big cigar and carrying big money bags to the bank, simplistic stuff. They had very stereotyped, hard to penetrate ideas about the United States on the one hand and on the other hand there was this sense of dissatisfaction. For example, all of them were eyeing me and my friend because of our clothes; we weren’t gussied up, we were just wearing the usual student garb. But they saw the difference and they didn’t like it, and it made me feel bad. They were also sophisticated about conveying information; they knew, for example, that we could not meet in any institutional situation. We had to take walks in the park if we wanted to talk, because it would have been bad for them to be seen with Americans. When they did talk they spoke in a very circuitous way. For example, I would ask, “What are you going to be doing with your studies,” and they would answer, “Well, there are so many possibilities, we will have to see what the future will bring.” What they meant was that this would be determined by the authorities, but they wouldn’t say that. There were a lot of examples like that. They were incredibly subtle with language.

MT: Did you visit any of the art schools?

AP: No, I was strictly in philosophy. But I did do some performances in Berlin, when I was struggling with the language. It came out of my attempt to make sense of the German language in terms of very basic syntax. I would be in some shop and after I’d complete the transaction, I would say, “Danke sehr schön,” which you don’t say. You can say “danke schön,” or “bitte schön,” but “sehr schön” means something completely different. People would give me this look and then engage me a bit more in conversation to see where I was from. I think they assumed from my appearance that I was Turkish, one of the Gastarbeiter, in which case the proper way of dealing with me was with a measure of contempt. After talking with me a bit more, it would become clear that I was an American. At this point, people would become very gracious. All those American dollars, this was a good time. It was interesting to me how visibly people’s responses changed. Having marked myself as a foreigner, first through my appearance, then through this syntactical error I was constantly making, there was this need to classify further, and clearly their behavior was very much keyed to their classification. The racial problem in Germany right now is with the Turks and the Gastarbeiter, and it was clear to me that they were suffering a great deal.

MT: Did you meet any of the so called Gastarbeiter in Germany?

AP: Well, yes, I lived right near the Wall in a student home, it is primarily a Turkish neighborhood. I met a lot of Turkish students and the people who came in to clean and take care of the home. You know, it’s funny, one of the things that fascinates me so much about “the Germans” is that they are so unalloyed in their responses. It seems that there is very little attempt to glaze their basic reactions with forms of civility, or superficial etiquette, or manners or anything like that. If I was an American, I was to be cultivated and my business was to be encouraged, and if I was Turkish, they would get me out as fast as possible. This surprised me a little bit because in this country I think we have gotten beyond that. There are still obvious forms of discrimination but under most circumstances the discrimination takes a more subtle form. People are not as overt in their prejudicial responses. On the other hand, I also made many friends in Germany and I found them really honest in ways that are conducive to deep friendships, really deep emotional contacts, in ways that I have rarely experienced. I mean they are just very special people.

MT: There is talk that the center of the art world is in the process of moving from New York to the Far East, that art will follow the new trade routes by way of the Pacific and that we have glimpses of this when Van Gogh is purchased for millions and taken to Japan.

AP: I don’t think we have made the move yet. My guess is that the next center will be in Los Angeles, as a kind of axis between New York and the Far East. But I do feel that we are indeed moving toward a more Pacific oriented culture and commerce. I really don’t know what to think of Van Gogh in Japan, whether it is a sign of the Japanese trying to assimilate into European culture, or whether it is a sign of Japan’s increased economic power, that they can basically do whatever they want. One would have to hypothesize a master plan, I don’t think that anyone is trying to take over the world.

MT: Are you presently involved with teaching?

AP: Oh yes, I’ve just gotten tenure at Georgetown, in philosophy, and I am at the moment trying to decide whether or not I should take a job at the University of Minnesota. I’m working on a book in philosophy, teaching and publishing regularly.

MT: Do you enjoy teaching?

AP: Teaching, oh, I love it, I love it. I direct dissertations, I teach graduate seminars, and then I have an undergraduate course and I enjoy it very much. The students who take philosophy tend to be feisty, conceptually. They ask a lot of “why” questions. They are not satisfied with easy answers, they tend to be skeptical; I really like that because students who take that kind of attitude are really exercising their intellect. It is wonderful to participate in the process of growth of someone’s intellect.

MT: What are these students planning to do with philosophy?

AP: Some go on to philosophy graduate school. It’s been very discouraging because there just aren’t any jobs available in philosophy, and haven’t been in a long time, but students with philosophy backgrounds tend to do exceptionally well in law school, because of their reasoning and analysis skills. So we get a lot of students who go on to law school or business school. There are a lot of consulting jobs opening up in medical ethics, business ethics, legal ethics. All sorts of issues, abortion, euthanasia—these are just the kinds of issues philosophers are trained to deal with.

MT: Are there no students studying philosophy for the pure joy of learning, for the sake of philosophy? Is the whole idea of training these students to prepare them for jobs in the corporations? Is there no thought of building an intellectual or thinking class?

AP: Well, as I say there are a few who go on to philosophy graduate school. Some of them get jobs, a very few of them will get tenure track positions, those who don’t get tenure will move around a lot, take one year substitute positions, spend a good portion of their young professional lives moving from university to university, year to year, because not that many jobs open up at tenure track level. Very often they will kind of settle in after a while in an adjunct position, or more than likely they will give it up and go to law school. It’s a very, very difficult situation in philosophy right now, and one can only hope it will get better. There are very few people I encounter who feel that they can study philosophy just for the luxury of knowing philosophy. Now when I took philosophy, I had already decided that I was going to be an artist, and I was prepared to drive a cab for the rest of my life. This was at age 19. But these students are very realistic, they are oriented toward having some measure of security. I’ve counseled a lot of students who were very conflicted about taking art or philosophy on the one hand and taking pre-law or pre-med on the other.

MT: Do you have any students in philosophy who are preparing to be writers, historians or visual artists?

AP: No, no I don’t. Art students tend not to take philosophy courses and I think that’s a big, big mistake. I think that one of the things that young artists have to learn in order to feel comfortable and good about their work is to take control of the public interpretation. This does not mean that they legislate what the works mean and no one else has anything to say about it, but they have to be able to speak up for what they think they’re doing, why they are doing it, what importance it has to them. Otherwise it is just going to be exploited by people who have a deadline, people who have an axe to grind about how all contemporary art is ridiculous, or that artists are just putting something over on them. It is very easy for an artist to just withdraw from the debate over contemporary art. To make it in the art world in terms of selling and showing, and then to have no control over what the work means in the public context, is to disown it. And that’s a terrible thing to do with something that you think is so important. For artists to have that kind of control and take that kind of responsibility, they have got to get educated, they have got to learn to think clearly, they have got to learn to read, speak—I think it’s just essential. One of the attractive features of the offer from this job in Minnesota is that I would be able to teach a course which would be designed to bring art students into a more intellectual context.

MT: We are perhaps the only society that jokes about the artist as stupid and ignorant. The myth of the artist as illiterate, inarticulate, ill-groomed is widespread here and the myth of the so-called Bohemian is perpetuated by the artists themselves. There are some societies still, where artists are seen as visionaries or prophets, and are spoken of with respect, as the first children of God, and where artists play an important role as members of the intelligentsia. Have you founds among your peers, people who joke about your having a doctorate in philosophy while at the same time being active in the arts?

AP: Yes, I get it from both sides. Most of the people I know in philosophy are not trained in the contemporary arts and they think of what I do as completely outlandish and weird. On the other hand I do get a kind of anti-intellectual strain from artist friends, who think that somehow by going on in philosophy and getting a doctorate, I’ve sold out, and that I’m trying to prove how smart I am. It’s a very surprising attitude because the arts in recent decades have become more and more theoretical and not always in ways I agree with. I am not a post-structuralist, I’m not a deconstructionist, but at the same time the arts have gotten more theory related. It seems as though there has been an increasing anti-intellectualism among artists, which I just think is pernicious, it’s self-defeating. There are these two sources of misunderstanding: from the artists about what it means to be a philosopher, and from philosophers about what it means to be an artist. Typically for most philosophers, their training in art ended somewhere around Impressionism and if you are not prepared to explain the history of art since Duchamp, most contemporary art is just not going to be intelligible to them.

MT: How do you combine all the various aspects of your creativity?

AP: Well, the way that I have been able to muddle through all of that—I get these images, sometimes they are graphic images, sometimes they are images of performances that I want to do, or installations, or something I want to draw or paint. I get an image and let it refine itself. Where my intellect comes in is in recognizing the significance. I don’t do every work I think about and some of the work I actually do, I discard. The intellect enters in figuring out what works really deserve to be realized, and should be shown to a public. It can take months, as you can see I am not a great producer, I don’t do two or three pieces a week, or anything remotely resembling that. I do between four and six pieces a year.

MT: It is said that true genius is seen in the act of selecting. Would you agree with that?

AP: Well, I would like to think so. I don’t think genius can be simply just putting out everything that occurs to one, that can’t be what it is.