Imaginary Lines

Tania Bruguera: Hablándole al poder — Talking to Power, installation view, 2018 [photo: Oliver Santana; courtesy of the artist and Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, MUAC/UNAM]

Share:

1.

LAS FRONTERAS MATAN: ¿DEBEMOS ABOLIR NUESTRAS FRONTERAS?

BORDERS KILL: SHOULD WE ABOLISH BORDERS?

This question is presented to the audience, and its members get the opportunity to vote: YES or NO. Two voting booths rehearse a democratic space in which the vote is personal and secret. Once counted, the votes are displayed in a numeric counter installed as a temporary wall at the entrance of the museum, along with a rendering of a squeezed world map in which all continental outlines touch one another, creating a sort of contemporary Pangea.1

Tania Bruguera: Hablándole al poder — Talking to Power, installation view, 2018 [photo: Oliver Santana; courtesy of the artist and Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, MUAC/UNAM]

2.

The first line was traced in the sand, but what was it safeguarding?

Empty space.

To protect, to be protected, to be safe. To sleep well, to be able to dream deeply and to not wake up in the middle of the night, sweating.

To be together in space, and to know that space.

To not be aware of danger.

What is there to protect? An idea.

It is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members … yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion. …Nationalism is not the awakening of nations to self-consciousness: it invents nations where they do not exist.2

If borders are built to protect a nation, then borders are to the idea of nations what a museum is to the idea of art—a physical space that protects, preserves, and encapsulates a group of ideas, technologies, and systems.

What would an equation for the correlation of safety, nationalism, borders, and imagination look like?

3.

A museum without art, without walls.

Imaginary lines, demarcating a territory that is invisible, unusable, yet real and effective. According to Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy, curator of the exhibition Mario García Torres—Let’s Walk Together, organized by Museo Tamayo in Mexico City in 2016, the exhibition took place at different venues throughout Mexico City that lie within a perimeter of 1,814 hectares. This corresponds to the total area of Museo de Arte Sacramento—founded by [Torres] in Northern Mexico—where the first iteration of Let’s Walk Together happened.3

The project involved designating a vacant plot of land as an art museum—a literal museum without walls. There is nothing to see at such a place, nothing apart from a natural landscape. The map of the Museo de Arte Sacramento was superimposed upon the map of Mexico City. The resulting irregular shape not only engulfed the main venue of the show—the Museo Tamayo—but also covered the area where activities and programs took place. The corners of the map were marked with piles of rocks to mark the expanded limits of the Museo de Sacramento.

A museum within another museum, equally real, but materially different.

Mario Garcia Torres, Where it Lays, Desolated, 2004-2015 [courtesy of the artist]

4.

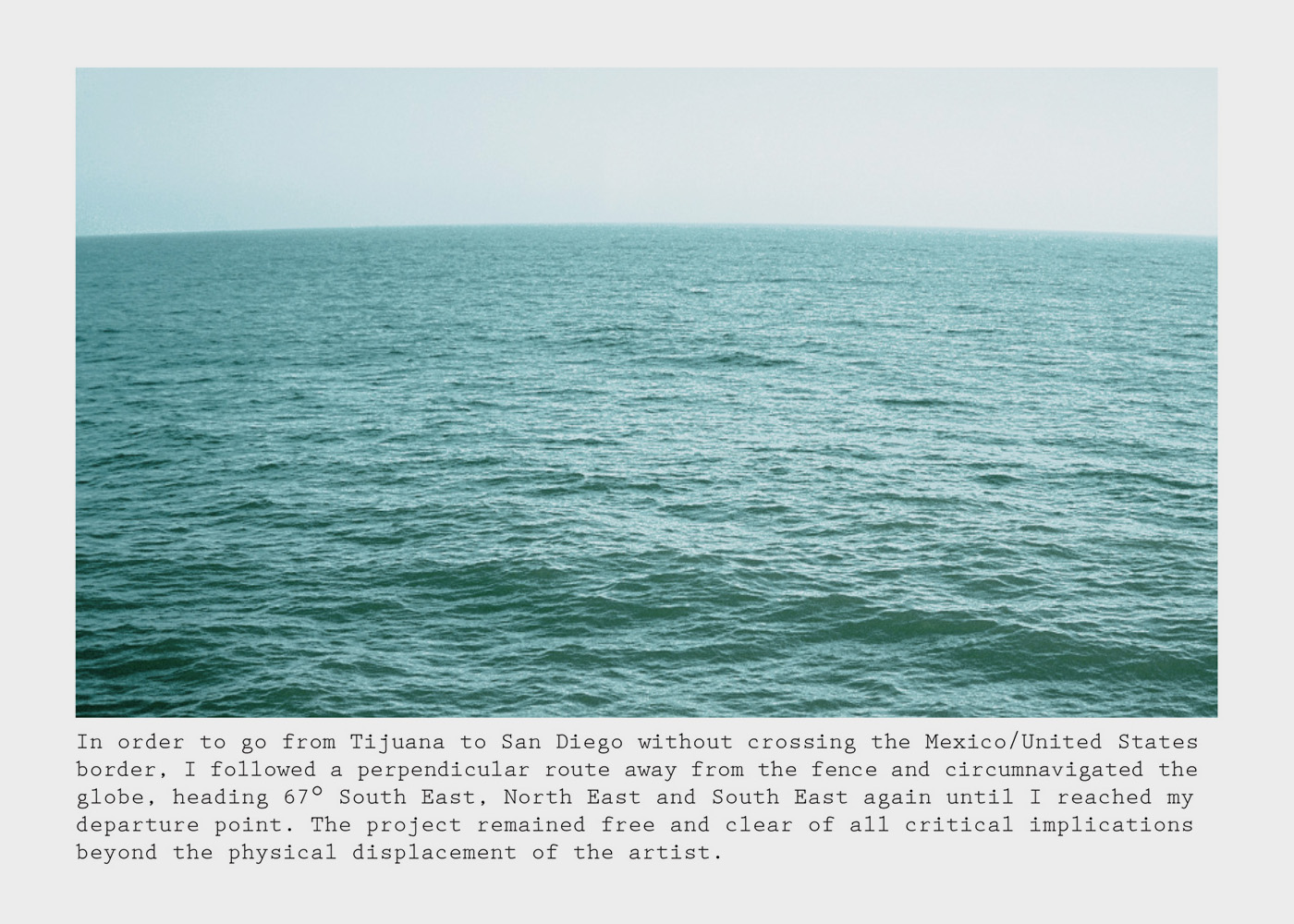

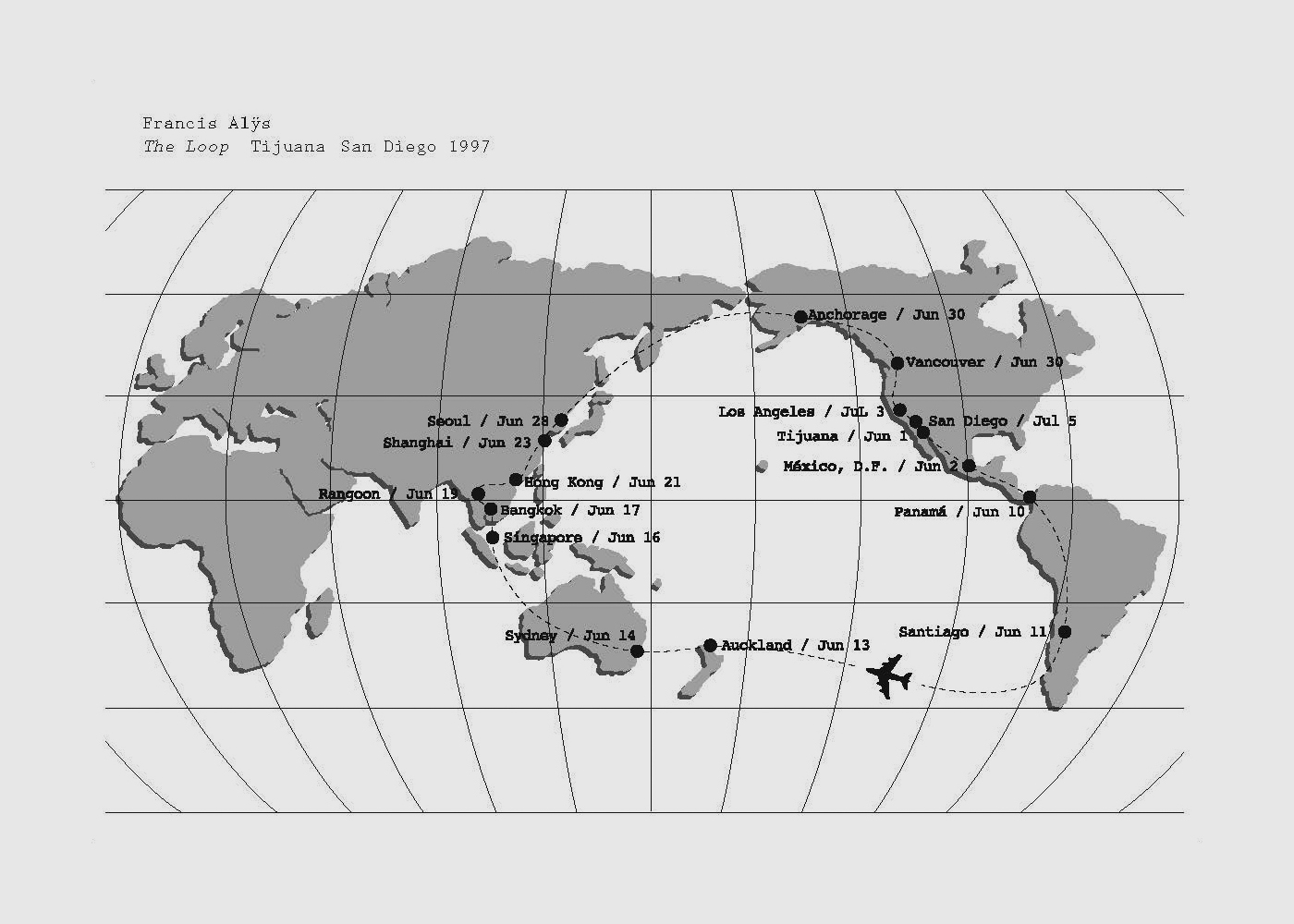

Sometimes the reversal of a system is the only truly radical action left. In 1997 the artist Francis Alÿs decided to reimagine and shift the usual way the US-Mexico border was crossed. As he has often said, his actions responded to the principle of “maximum effort, with minimal result.”4 The work, titled The Loop, was done as part of inSite 1997. Founded in 1992, inSite commissioned site-specific works by local and international artists to stress the reciprocal conditions of the border corridor in between Tijuana and San Diego. As stated by Alÿs, The Loop was an attempt to travel from Tijuana to San Diego without crossing the border: “I will follow a perpendicular route to the dividing wall. I will circumnavigate the Earth, moving 67° SE, then to the NE, and then again to the SE until I arrive to my departure point. The objects generated during the trip will be a testimony of this project; they will be free of all critical content beyond the physical journey of the artist.”5

5.

Can we imagine a borderless land? One that is expanding and contracting in relationship to the environment or its inhabitants? Can we imagine forms of governance that are unrelated to power? Could we retrace lines to soothe injustice? Can we confront our own greed, our own systemic paradoxes? Are there other ways to feel safe?

Francis Alÿs, The Loop, 1997, postcards, 4.3 x 5.9 inches [courtesy of the arist and Galerie Frank Elbaz, Paris/Dallas]

6.

Listen to poet Amy Sara Carroll. She understands that economy is not only an organizational technology but also a symbolic system. In her writing she traces the complex relations between Mexico and the US through historiographic exercises, attributing the complexities therein to the birth of neoliberalism. Specifically she addresses the years 1935 and 1938, when president of Mexico Lázaro Cárdenas orchestrated initiatives to end gambling in Baja, CA, and to expropriate national oil. She touches upon Roosevelt’s good neighbor policies and the “Bracero Program”—a diplomatic agreement for temporary workers—as the milestone of “Mexico and [the] United States’ collaborative commitment to the eventuality of a North American neoliberal transition predicated on a continental re-division of extralegal alienation and racialized and gendered labor and resource extraction.”6 After the insurgence of “maquiladoras” in US-Mexico border cities in the 1970s, the game board was set. What Carroll calls a “representational economy,” and the exploitation of gendered cheap labor, along with the new figure of the illegal alien, were all integrationist continental philosophies predating NAFTA.7

A representational economy: representing abuse, injustice, gendered exploitation, and inequality often disguised as good intentions, handshakes, and diplomatic hugs. For Carroll, the proto-neoliberal triggers and the Chicano movement in the 1980s allowed for what she calls “the San Diego-Tijuana corridor as a hotspot of the greater Mexican culture wars.”8 In this sense, the relevance and radicalism of art forms in the San Diego-Tijuana corridor had a stronger relationship with Mexico City in the early 1990s than with any other cities in the country. About Mexico City, Carroll cites Irmgard Emmelhainz, who wrote that it “became key in the imaginary of contemporary art, a metaphor or allegory of the shifting geopolitical borders.”9

Mario Garcia Torres, Where it Lays, Desolated, 2004-2015 [courtesy of the artist]

7.

After the floods of the 2080s, in which all coastal cities of the East were abandoned, Nashville, TN, became the new home of Wall Street, as well as the operations base for the Space Colony Agency (SCA) and its uninterrupted missions to Mars and Jupiter’s moon Europa. In 2028, during President Trump’s last year in office, after he amended the constitution to allow presidents a third term, backed up by a Republican majority in the Senate and Supreme Court, two main segments of the border wall were completed in California and Texas. The states of Arizona and Nuevo Mexico started conversations with the Mexican government to surrender their territory back again and become the 34th and 35th Mexican states. The initiative was finalized in 2040, and after almost a decade of public debate, the Mexican government announced the voluntary annexation of New Mexico and Arizona, calling them the “white states,” a term used to describe the lack of interest in preserving US sovereignty.

Meanwhile, California became the first “open source state,” a rhizomatic organization based within a network of communities where all forms of morally oriented, capitalist-driven regulations where dismissed or inhibited. They surprisingly avoided all remaining traces of emotional adherence to nationalism and national identity, particularly after the referendum to expel all Hollywood operations to Atlanta, where the kingdom of celebrity culture had proliferated extensively. Although they were still part of the United States, Californians issued their own passports and came to be regarded more as a colony than as an incorporated state.

Texas, on the other hand, became the first oil-based economy to be detached from the United States. Texans were able to complete a perimeter border wall along their new country, using the remaining fragments of Trump’s pre-Great Floods wall. The government of the United States published a ban on naming the country America in an unprecedented gesture acknowledging past centuries of imperialism in which the colloquial use of the name was rooted. Outside of California and Texas, citizens of the remaining country were compelled by law to refer to themselves as “US-Americans,” or even “US-ians,” which became a popular demonym. The remaining US states granted extra funds to support conjoined federal efforts for a new geography class in public high schools, ensuring that all US-American citizens were able to locate their own country on the map, to learn the new borders of the country after environmental and political shifts, and to identify clearly North, Central, and South America. In 2134 the Mexican government announced the “New Bridge” initiative, a construction program that would build more than 2,000 bridges over the remaining segments of wall in California, Arizona, and New Mexico, allowing animal species to return to their habitual migration patterns.

8.

Colonial formats are trying to be decolonized by shifting quotas of representation, and/or by trying to redirect visibility to formerly neglected shapes. It is not the content but the format itself that is the colonizing agent, and the thing that should be redistributed.

Call it the acceleration after Internet era, call it the end of NAFTA, call it the exponential globalization of politics and economy: the lack of interest in border-addressing Mexican arts in the past decade is real.

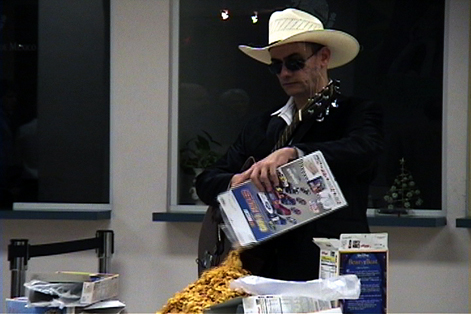

Eduardo Abaroa, Narcocorrido / corn flakes, 2001, performance, digital video on 4:3 aspect ratio monitor, table, cover table, bowl, spoon, guitar, music magazine and music notes for guitar, 50 Corn Flakes cereal boxes, red vinyl circle (transfer), mexican norteño outfit, sombrero, boots, guitar, tripod, dimensions variable, [courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City]

9.

The “Artificial States” are ones existing in some countries in “which political borders do not coincide with a division of nationalities desired by the people on the ground.”10 Take for example Wyoming and Colorado, which are represented as rectangles; disregarding the curvature of the earth, they demonstrate colonial methods of mapping. They are actually polygons. By introducing the problem of “division”—or “dividing” land accordingly to a person’s or a political group’s interests—we have on one hand, the “official” representation or visualization of this impulse … say, maps. On the other hand, we have the physical, geographical, and cultural empty spaces this gap creates.

10.

Consider these words in what is, by popular taste, one of the best narcocorridos ever, “Pacas de a kilo” (“One-Kilo Packets”) performed by Los Tigres del Norte:

Me gusta andar por la sierra

[I like to hang in the mountains]

Me crié entre los matorrales

[I was raised through bushes]

Ahí aprendí hacer las cuentas

[There, I learned about accounting]

Nomás contando costales

[Only by counting sacks]

Me gusta burlar las redes

[I like to outwit police checkpoints]

Que tieneden los federales

[Laid by the Federals]11

Such lyrics—along with those of 11 other songs by Chalino Sánchez, Los Razos, and Capos de México—constitute the musical repertoire that either a solo player or a group must play until someone, intentionally or not, steps into a red circle on the floor in front of the performers. When a person steps into the perimeter of the red circle, the performer should stop playing and walk toward a table where 50 boxes of corn flakes wait to be emptied and dispersed over a bowl and spoon, which rest on that same table, until the red circle has been cleared, when the corn flake rain ends, and the narcocorrido concert resumes.

11.

Not through, but around. That’s how you cross a line without touching it.

This feature originally appeared in ART PAPERS “Borders, Barriers,” Fall 2018/2019

“Imaginary Lines” is part of a series of “constellations” that Humberto Moro has created around different subjects since 2010. These texts use a format with a multiplicity of condensed references in the form of lists, not only for what they mean but also for what they create in proximity to each other.

Humberto Moro (b. Guadalajara, 1982) is curator at the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, GA, where he has organized solo exhibitions by such artists as Oliver Laric, Liliana Porter, Cynthia Gutiérrez, Pia Camil, Mariana Castillo Deball, Tom Burr, and Yang Fudong. Moro has held positions with ZONAMACO and Museo Jumex in Mexico City. Moro has curated projects at El Museo del Barrio, Park Avenue Armory, Johannes Vogt Gallery, and the Hessel Museum of Art in New York; La Casa Encendida in Madrid; and Museo de Arte de Zapopan. Moro holds a MA in curatorial studies from the Center for Curatorial Studies (CCS), Bard College.

References

| ↑1 | Tania Bruguera, exhibition materials for Talking to Power / Hablándole al Poder, solo exhibition at Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City, curated by Lucía Sanromán and Susie Kantor, and organized by the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco. (2018). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso Books, 1983): 6. |

| ↑3 | Tamayo Museum, exhibition materials for Mario García Torres: Let’s Walk Together, curated by Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy, (2015): http://museotamayo.org/exposicion/mario-garcia-torres-br-caminar-juntos |

| ↑4 | Francis Alÿs, “When Faith Moves Mountains,” francisalys.com (2002): http://francisalys.com/when-faith-moves-mountains |

| ↑5 | inSite (2013): http://insite.org.mx/wp/en/insite |

| ↑6 | Amy Sara Carroll, REMEX: Toward an Art History of The NAFTA Era (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2017): 235–236 |

| ↑7 | Ibid., 239 |

| ↑8 | Ibid., 244 |

| ↑9 | Ibid., 135 |

| ↑10 | Alberto Alesina, et al., “Artificial States” (February 2006, revised November 2008): https://williameasterly.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/59_easterly_alesina_matuszeski_artificialstates_prp.pdf |

| ↑11 | Los Tigres del Norte, “Pacas de a kilo [One-Kilo Packets],” written by Teodoro Bello (1993), translated by the author, Fonovisa. |