Dr. Huey Copeland

Each year, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta presents the David C. Driskell Prize for significant contributions to African American art history. ART PAPERS editor Sarah Higgins met up with the 2019 award winner Dr. Huey Copeland on the eve of his award celebration dinner to discuss his influences, the stakes of art history, and pushing the binaries of art historical imagination.

Share:

Sarah Higgins: You are a professor at Northwestern University and you’re affiliated with a number of departments in that capacity, but you appear professionally to identify really strongly as an art historian first and foremost. You’re clearly working in a really cross disciplinary and intersectional way, and you’re also focused pretty exclusively on the contemporary in your work. For some time now, it seems to me that folks with art history backgrounds tend to passively distance themselves from that disciplinary space, aligning more with the curatorial or the educational or the critical aspects of the work to which they are applying that background. You see this [tendency] reflected in the trends of art history departments leaning more towards curatorial certificates. So why stake your flag in art history?

Huey Copeland: I stake my flag in art history in part to be clear about my own disciplinary formation. I’m trained as a historian of modern and contemporary art by social historians of art, often focused on the 19th century. Being affiliated with a number of different units at Northwestern—performance studies, critical theory, African American studies, art theory and practice, gender and sexuality studies—is a way of indexing my approach to art-historical practice, particularly the African diaspora, which necessarily has to be interdisciplinary if we think about the way in which African and African diaspora cultures have unfolded. I think we also want to have a very sophisticated, nuanced language when thinking about the many divisions within blackness, which is why I think an intersectional approach, building on the work of Kimberlé Crenshaw and Jennifer Nash, has been so important for me. So that’s all to say that these kinds of engagements in a number of different fields are part and parcel of my understanding of what art history is and can be, which is capacious, promiscuous—looking to a variety of sites and discourses and disciplines for its methods in order to do the work of putting a sensuous iteration of human expression into its proper context.

I’ve tended to work on the contemporary in addressing these questions. But my training is as an art historian. My impulse is to figure out the ways I need to frame this work, given my experience of it, but also the discourses submerged around it, in order to make an intervention that’s going to forward our understanding of that practice. I think we’re in this moment [when] art historians are very much engaging with people from a number of different fields who are working on visual things, and I think that really enriches the conversation for all of us. It helps us move away from some of the doxa of art-historical practice and some of the protocol and processes that are inherently biased and patriarchal and exclusionary, like notions of a masterpiece, or the canon, and instead to have a more labile and flexible way of framing the work of art that speaks to its conditions of emergence as opposed to imposing some already authorized art-historical understanding of why it matters and is compelling.

SH: I come from a curatorial background, and I also see it as an inherently [cross-disciplinary] and interdisciplinary space. In some cases, I think the popularity of the curatorial as a field of study is responding to critiques of the art-historical disciplinary space. I think people can feel like it’s restrictive, mired in master narratives, unable to break free of those things. It’s so refreshing to hear it just laid out, like, “No, it can be fixed. And here’s how.”

HC: Yeah! Thank you! We really saw a certain kind of transformation happening in the humanities with the rise of multiculturalism in the late 1980s and early 90s, and those lessons have really borne fruit in fields like English literary studies. If you look at studies of 19th-century American literature, they of course are thinking deeply about questions of race and building on the scholarship of people like Saidiya Hartman. I don’t think you could say the same thing if you were to look at 19th-century American art history. Is it dealing as deeply with questions of slavery and cultural difference, or is it suppressing those because it hasn’t figured out the ways to perhaps discuss or engage that work? I think scholars really doing exciting work on these questions—like Jennifer Van Horn, who is at the University of Delaware—are really trying to think about questions, like “what were the responses of the enslaved to works of American art?” that [allow] us to push against the narratives that centralize certain kinds of objects, certain kinds of producers, in order to think more broadly about the entire cultural/political ecology that makes these works of art possible. Who are they for? What work are they doing in the service of power? And how do we both understand what’s there in front of us but also understand what it’s covering over?

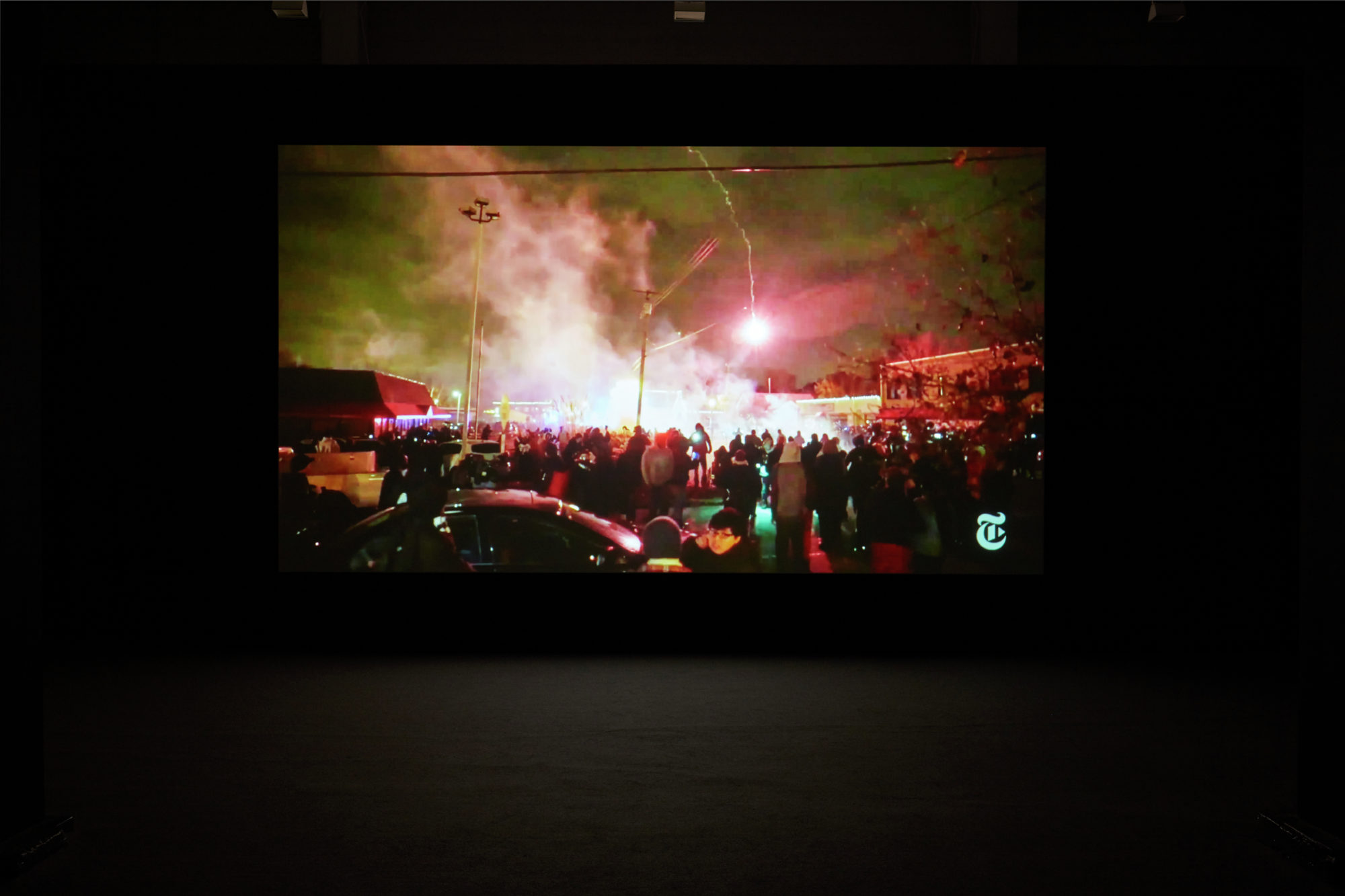

Arthur Jafa, Love is The Message, The Message is Death (still), 2016, single-channel video [courtesy of the artist and High Museum of Art, Atlanta]

SH: You’ve written [in] a broad range of formats and [for a range of] publications, but you’re probably most well-known for your book, Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America, which came out in 2013. I know you’ve had a chance to see the new installation of the High Museum’s permanent collection during your visit. I personally was completely blown away by Arthur Jafa’s work Love is the Message, the Message is Death, which I’d read about but never seen installed. Many of the artists you’ve written about are incorporated into that new installation. Any favorite moments, favorite pairings that jumped out at you when you saw it?

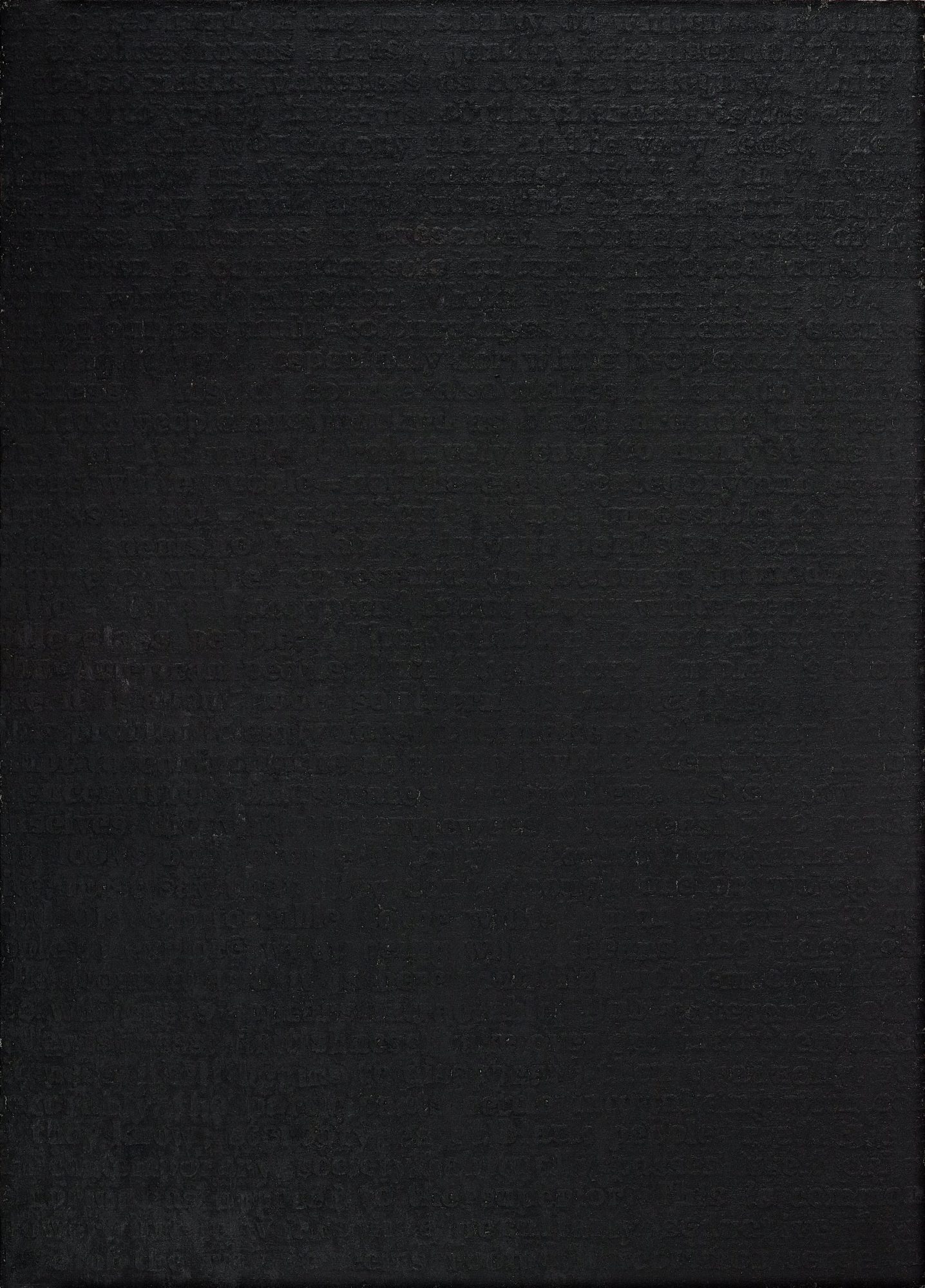

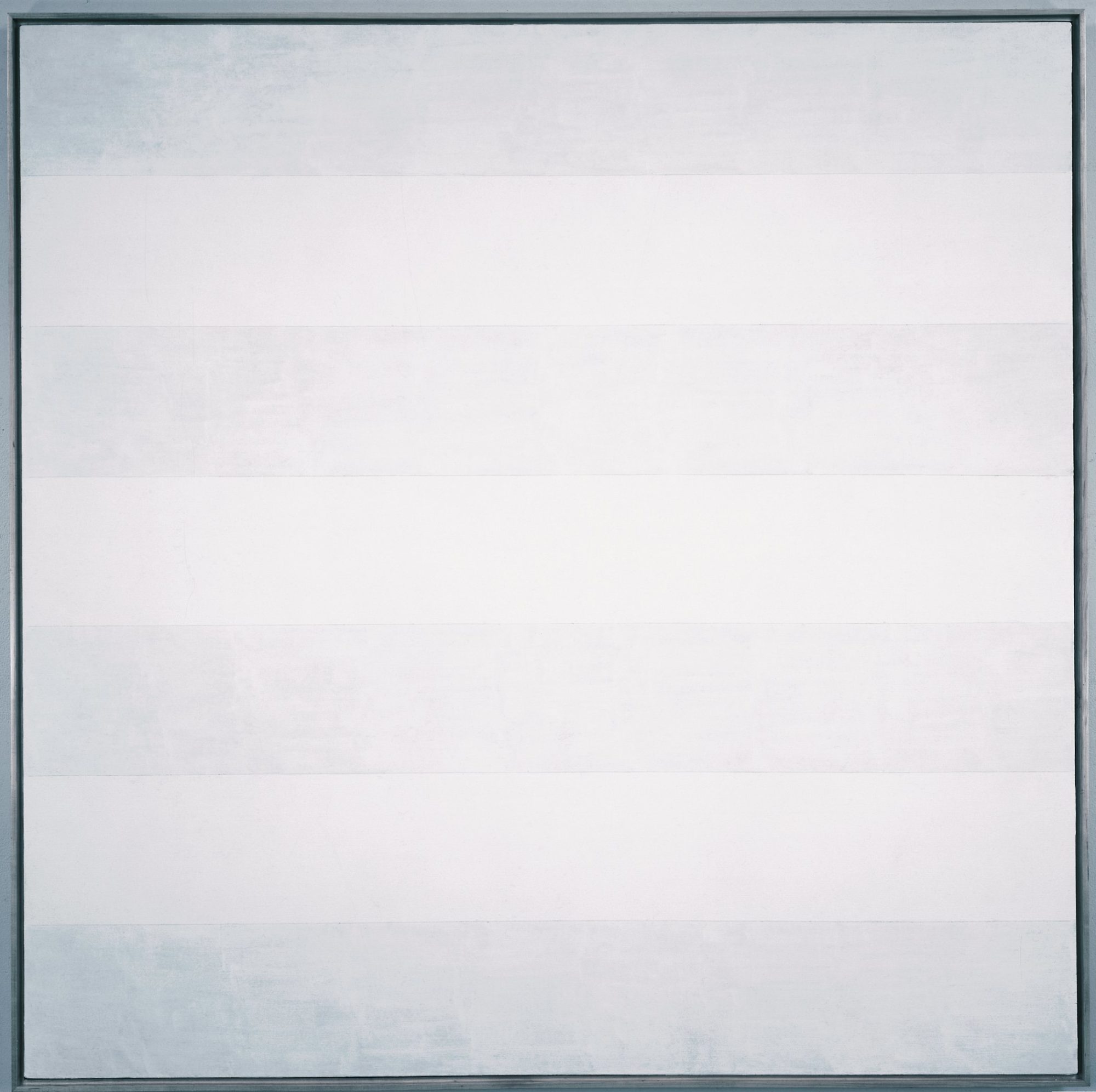

HC: Yeah! One particular, wonderful moment is seeing one of Glenn Ligon’s monochrome paintings across the room from an Agnes Martin painting. These two artists—two queer artists—very differently working with the monochrome, very differently thinking about figuring identity, but still incredibly invested in the experience of painting as makers and viewers of their own works, create this really rich dialogue. That underlines the variety of audiences and experiences it can speak to but also speaks to a wonderful toggling or play with a certain kind of historical narrative. Because in an earlier moment one might have expected to see, say, Ad Reinhardt across from that Agnes Martin. So to be able to have Ligon there—to both have his own dialogue with Martin but then to recall this longer history of monochromatic black abstraction—really creates a rich productive moment of encounter with the objects themselves as they immediately face off against each other, and have very different visual qualities that activate your eye and your body in completely different ways, but also between the two of them, opening onto a much longer historical narrative about abstraction in modern contemporary art.

(left) Glenn Ligon, White 18, 1994, oil stick, canvas, wood panel [courtesy of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta]

(above) Agnes Martin, Untitled #3, 1994, acrylic, graphite, canvas [courtesy of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta]

SH: That Ligon-Martin pairing is just to the right as you exit the video gallery where Love is the Message is shown, and I feel like there’s a kind of accessibility and entry point created by having just experienced a very contemporary video work that really puts you in the headspace of conversations that might not have been on your mind when encountering two minimalist works, yet you walk out and there they are.

HC: Yes! And thinking about that is interesting. I didn’t walk through and re-watch Love is the Message again, so I didn’t have that exact experience, but I imagine it would be both calming and disturbatory moving from Love is the Message to these canvasses that give you a certain kind of visual respite, but at the same time are equally charged in the ways in which they’re engaged, in which they’re visually trafficking, even if not directly, in the same political/visual ecologies that Jafa is working through in Love is the Message.

SH: Yeah, it really refuses the idea of minimalism as an escape from content.

HC: Exactly. I think we’re in this moment where we’re able to really push the binaries that have not only structured the art-historical imagination, but also how we organize and structure the world more broadly. So, this opposition, say, between figuration and abstraction, in that moment of the show is completely blown apart because you move out of Love is the Message, which in many ways has all of these incredibly wonderful, abstract, difficult, opaque moments to looking at the Ligon and the Martin, which of course are very much abstract, but they open themselves to a kind of reading, literally in the case of Ligon’s work, to a proximate bodily engagement that allows one to think about a bodily habitus in the work. It’s on this level that we can start to think about the continuities and differences between [what seeing “abstract” forms does to you and] the work on your body that Love is the Message does, which is much more about the nervous system in terms of really reaching and touching you and engendering a visceral response.

SH: Yeah, yeah. You feel it in your gut, for sure. It’s funny that you mention the dichotomy between figuration and abstraction. I’ve been in lots of conversations about the ways in which black and African American artists are experiencing increased visibility as art institutions are finally waking up to a really strong demand to catch up with representation in their collections and exhibition programs. As these still pretty exclusively white spaces are affecting the market, they’re affecting visibility—artists’ careers are getting scooped up and made.

I’m interested in how this moment could be breaking or creating new kinds of containers for the formal, material, and symbolic spaces that black artists are being lifted up within, and how that is reigniting long-standing conversations about figuration versus abstraction in terms of representation. I’m curious—especially since Bound to Appear addresses the site of blackness in multicultural America—do you see all of this shifting that site?

HC: I think there can be a tendency to reinstitute certain kinds of binaries between abstraction and figuration, but if we think about the history of modernist abstract painting, even just limiting it to a Euro-American context, we could think back to, say, Helen Frankenthaler and her flirtation with landscape, or we could think about Kenneth Noland and his engagement with the logic of design technology and corporate logos. To say that there’s a certain kind of pure abstraction or pure figuration is not helpful, I don’t think, because one is somehow always contained within the other.

We’re in a moment [when] we not only can see these longer histories of black abstract and figurative practice that contemporary artists are engaging with, but [also] the ways in which they’re remixing, working with, and working across those different boundaries and traditions. I think there can be a tendency to put those kinds of practices into categories or containers which delimit the kind of actual play that the works and the artists are engaged in, with, and through each other in implicit and explicit ways, and impoverish our understanding of the complexity of the visual field that’s being navigated by these artists. I think the question becomes, “What is the relationship between that market visibility, institutional support, and art-historical practice,” right?

Huey Copeland headshot, 2017 [photo: Bonnie Robinson; courtesy of the artist and High Museum of Art, Atlanta]

HC (cont.): There are a number of African American artists working abstractly, such as Howardena Pindell, Ed Clark, Jack Whitten, who are having a moment now, and I think we have to be excited about that moment, but [also have] to question to what extent is this the market wanting to diversify the kind and variety of abstract, decorative, seemingly apolitical products that it can supply for its consumers, now inherently blackened by the identities of their makers to add this additional charge to their relevance. And that’s perhaps a critical and worried perspective, but I think it’s something that we have to think about. Though this market legitimization and take-up are useful, I think it’s not only about these artists getting their due economically but also [about] asking what it means in terms of institutional acquisition. What does it mean in terms of the exhibition of that work, and what does that mean in terms of incorporation of that work into the museums’ and the fields’ larger histories and narratives? That’s what we need to be tracking. Is there a kind of through line that market legitimization can open up, leading to a more careful, nuanced historical evaluation of the work?

In this moment [when] so many institutions are realizing they are behind, as you put it, [and] there is a kind of urge, and a correct one, to collect African American art. But I think one wants to do it in ways that are both mindful of a longer history of African American artistic practice and of the space of collection. Because we do live in this moment of “presentism,” [when] contemporaneity is such a market, academic, and institutional force. I think there can be a tendency to think, “Oh, we’ll get a work by this really contemporary artist,” which is great, fantastic, you should be supporting that artist, but you know what? There is a really fantastic black woman artist who was working in the 1940s you could have in your collection who would change how we think about and narrate an earlier historical moment. So, I think we need that depth and that training and knowledge, so it’s not as if you’re walking through a collection and, hey presto, it’s 1994, Kara Walker appears and suddenly there are black people.

Glenn Ligon, White 18, 1994, oil stick, canvas, wood panel [photo: Marci Tate Davis; courtesy of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta]

Agnes Martin, Untitled #3, 1994, acrylic, graphite, canvas [photo: Marci Tate Davis; courtesy of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta]

SH: As if at the very moment when institutions start collecting more actively, suddenly African American artists were conjured into existence.

HC: Right! As opposed to thinking, “well, what is this kind of longer history of production, and what are the conditions of segregation and exclusion which prevented us from seeing, and understanding, and incorporating that work into these galleries?”

SH: Absolutely. At ART PAPERS we’re working on an issue that looks at art and political efficacy. I have strong opinions about the relationship—or nonrelationship at times—between art and activism. We’re considering a lot of questions as we build that content. I would love to hear your thoughts on some of them—such as, what comes to mind for you when you consider art’s ability, historically or today, to perform a function that can be seen as activism? What do you see as the role of art institutions such as museums in making or holding a space for political discourse? What about educational institutions? Where do we have the hard conversations within institutional space? And, do you think that, at times, there’s a crisis of criteria when we talk about art and activism, or art as activism?

HC: Yeah, those are all really good! Oh, goodness! I needed to put my smart-cap on. Can you repeat the third question?

SH: The third one was: do you think that art making and activism suffer from a sort of crisis of criteria?

HC: I want to answer that one!

SH: Awesome. [laughs] You’ll take criteria for 1,000!

HC: [laughs] The question of criteria is a really interesting one, because there was a way in which art history developed a lexicon of criteria, particularly in the American context in the 50s and 60s, that was based on a kind of formal analysis, and then we saw a shift in the 60s and 70s with the emergence of a post-structuralist mode of critique that was really more about trying to understand the artist’s work on the signifier, to paraphrase Rosalind Krauss. That opened onto a whole new arena for thinking about what the criteria were that mattered to artists’ practice, and I think those of us with an interest in art and its engagement with activism and politics often try to think about “What is the efficacy of this work politically or aesthetically?” and that became their criterion for judging the success or failure of a given project or intervention. But I think that is to perhaps saddle the work of art with too many, or maybe not enough, expectations, depending on what the ontology of the work of art is.

I think what has to develop [is] a set of criteria for understanding and evaluating the work based on the understanding of what its ambitions are, and what its conditions of possibility and restraint are in terms of activating or shifting that field. Understanding the value or efficacy of a work is something that has to happen in a nuanced way, in a kind of long durée. To give one example: Fred Wilson’s 1994 installation at the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art, which was called Insight: In Site: In Sight: Incite: Memory. I think it was a really successful intervention in that space because he was invited to build on extant programming, [on] interventions that were trying to incorporate the history of African Americans into telling the story of the Moravian community there in North Carolina. I think that work was able to be effective because in many ways there was a political will already in place in the institution to change and actively transform the way in which they were narrating history. So we have to understand a work such as Wilson’s as being part of a larger scenario, history, ecology that is part of the unfolding of the work. How can we develop criteria for evaluating it aesthetically, culturally, in ways that don’t merely end at “is it efficacious or not?” But how do we think about its ongoing effects and its disturbatory potential, whether we judge the work a success or a failure in terms of activating us as viewers, as citizens, and as participants?

This exchange has been edited for publication.