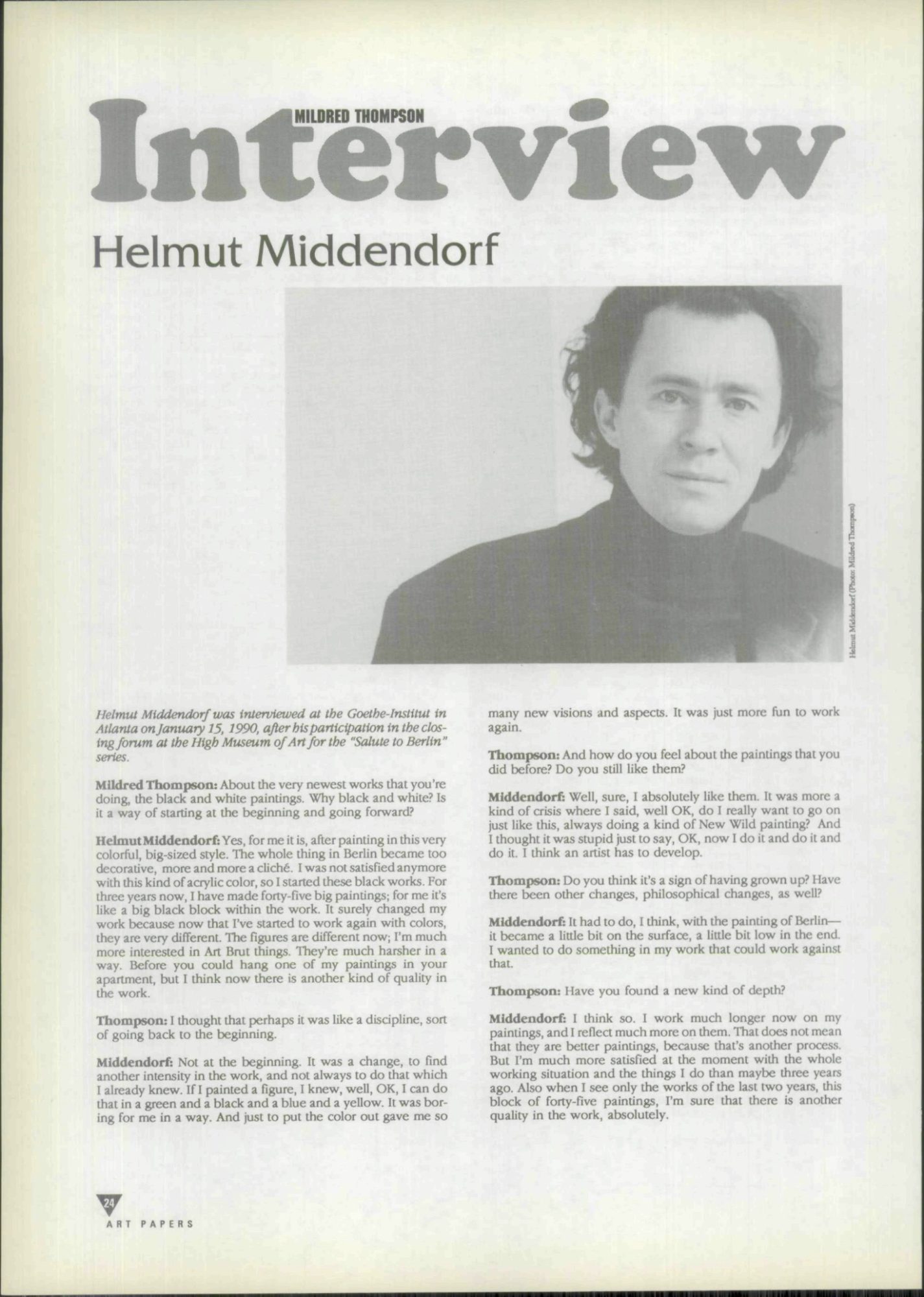

Helmut Middendorf

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS March/April 1990, Vol. 14, issue 2.

Helmut Middendorf was interviewed at the Goethe-Institut in Atlanta on January 15, 1990, after his participation in the closing forum at the High Museum of Art for the “Salute to Berlin” series.

Mildred Thompson: About the very newest works that you’re doing, the black and white paintings. Why black and white? Is it a way of starting at the beginning and going forward?

Helmut Middendorf: Yes, for me it is, after painting in this very colorful, big-sized style. The whole thing in Berlin became too decorative, more and more a cliché. I was not satisfied anymore with this kind of acrylic color, so I started these black works. For three years now, I have made forty-five big paintings; for me it’s like a big black block within the work. It surely changed my work because now that I’ve started to work again with colors, they are very different. The figures are different now; I’m much more interested in Art Brut things. They’re much harsher in a way. Before you could hang one of my paintings in your apartment, but I think now there is another kind of quality in the work.

Thompson: I thought that perhaps it was like a discipline, sort of going back to the beginning.

Middendorf: Not at the beginning. It was a change, to find another intensity in the work, and not always to do that which I already knew. If I painted a figure, I knew, well, OK, I can do that in a green and a black and a blue and a yellow. It was boring for me in a way. And just to put the color out gave me so many new visions and aspects. It was just more fun to work again.

Thompson: And how do you feel about the paintings that you did before? Do you still like them?

Middendorf: Well, sure, I absolutely like them. It was more a kind of crisis where I said, well OK, do I really want to go on just like this, always doing a kind of New Wild painting? And I thought it was stupid just to say, OK, now I do it and do it and do it. I think an artist has to develop.

Thompson: Do you think it’s a sign of having grown up? Have there been other changes, philosophical changes, as well?

Middendorf: It had to do, I think, with the painting of Berlin—it became a little bit on the surface, a little bit low in the end. I wanted to do something in my work that could work against that.

Thompson: Have you found a new kind of depth?

Middendorf: I think so. I work much longer now on my paintings, and I reflect much more on them. That does not mean that they are better paintings, because that’s another process. But I’m much more satisfied at the moment with the whole working situation and the things I do than maybe three years ago. Also when I see only the works of the last two years, this block of forty-five paintings, I’m sure that there is another quality in the work, absolutely.

Thompson: How do you think that the public is going to receive your new works, the people who know you as a lot of color and cliché? Because the public often demands “paint that again.”

Middendorf: I wanted to work exactly against this shit, you know, so I said, “I have to disappoint them.” In the beginning I showed these works in Stockholm and the people were really astonished and said, “What is he doing? Why is he doing that?” But in the end, the critics were really very good, in how they wrote about it, because they really had to look again on the painting. For the first time in years, they really wrote on painting. And when I did the show last February in New York, there was a review by Donald Kuspit, and what he wrote about the work was extremely good and to the point.

Thompson: Do you feel that your reputation as a Wilde is in competition with the work that you’re actually doing?

Middendorf: No, not at all. I’m an expressionist artist, and I don’t think in these terms. Neue Wilde—that makes no sense. My work is not so much a one-way ticket…

Thompson: Yes, but the public has put you in the category.

Middendorf: Yeah, sure, but we have to work against that and show them that there are other facts in the work. I did a show in Berlin in November in the DAAD Galerie with drawings from 1976 to 1979 to show that already before there was another aspect in the work, more ironic. In the beginning, people asked me “Why do you show drawings from ten years ago? Show your new drawings.” I said, ‘No no no, I want to show these other drawings.” You cannot make it too easy for the people.

Thompson: Do you think that your old public will grow with you, or will you have a new public?

Middendorf: Yes, you have to. But not in a way that says, I don’t want to have anything to do with this old work; not at all, I love it. I think that the concept of heftige Malerei [violent painting] was really fascinating for six or seven years. It doesn’t work all the time, because the people grow up, they grow older, they have other experiences, including experiences with the art market; they see other painters. That has to do with your own development, what you want to show, what your interest is in painting.

Thompson: Are you concerned about a public?

Middendorf: What is a public? For me, a public is ten people who I really can take seriously. In general, if this newspaper writes this, or this person says this, it makes no sense. I think very few people are really interested in painting. They’re more interested in fashion. But that’s how the whole system works today. They try to make new trends, with neo-geo and so on. But we were also a trend in that way. And you have to reflect that as an artist—what is your role in the game, do you want to play that, are you an art market artist or what are you?

Thompson: Before, your paintings were about life in Berlin, the political situation of Berlin. There are many facets of painting the figure. Black and white is said to be more abstract than painting in color. Would the subject matter be more psychological?

Middendorf: Yes, that’s right, my interest has changed. In the early ’80s, the paintings had much more to do with my experience of life. The new works are much more reflections on it. They’re not like, OK, I was looking at music and now I paint music. Now they’re more like, what is music. I made a new oil painting that is called The Black Singer, and if you compare these with the singer paintings from before, this has nothing to do with the singer. My inspiration came from a little African puppet. The work is also much more abstract. To paint the same thing over and over is absolutely stupid, because you’re a prisoner of yourself. I think it would be better to stop than to go on like that.

Thompson: Do you see any changes in your life style also? Because when there is a break in your work, it goes all the way through, you think differently, you live differently.

Middendorf: Yes, I think differently. Today I am much more sarcastic about the whole thing, with more distance from the art world. I take more time, I’m more relaxed. I think that it was a fantastic period in the beginning, and that it was absolutely right to do that. But I think totally different than before.

Thompson: Were you in any way prepared for the sudden international popularity that you received?

Middendorf: I think that it was not so sudden. For Salomé I think it was like a hammer. He was shot to the stars in the beginning, and then he had to find the way back. For me it went not so…well, it went. From one day to the other, I had the show with Fetting at Mary Boone, and within two months we had the show. But on the other hand, from the beginning I had more distance on the whole thing than Salomé. I couldn’t take so seriously what they told me.

Thompson: Because you know that today’s news wraps tomorrow’s garbage.

Middendorf: Absolutely.

Thompson: But very few people realize that. And I have seen so many people washed out by success. We’re prepared to fail, but nobody prepares us for being suddenly famous.

Middendorf: But it was also such an extreme pleasure to have this success, and to have these possibilities. We worked like hell. Our problem was much more in that thousands of people want a painting. We didn’t refuse too many of these offers. It isn’t good to have this many shows in the beginning. We were really under stress. But I think that the Italians, and Schnabel and Salle, all these people who were involved in the beginning reached the same conclusion. There was such an explosion of interest in painting. That was a much bigger problem. How many paintings can I really do, and what is serious, what is unserious? The more important thing was to see how the art market worked, and to ask, really, what is my role in the whole thing? Am I a pawn in the game or what?

Thompson: Do you feel that perhaps you were a pawn?

Middendorf: Not a pawn, but surely if I reflect, then I should have refused two or three shows. On the one hand, you can’t handle the whole international thing, you don’t have the experience. On the other hand, it was good that we had our own gallery before [the Galerie am Moritzplatz in Berlin], because we knew how it worked, what a gallery is, what can a gallery do for you. And we had a lot of work in the beginning that was really important. We had hundreds of paintings.

Thompson: Did you ever get together as a group and discuss what was happening to you?

Middendorf: In the gallery, sure, but when the big success came afterward, no. Success changed the people too much.

Thompson: Did you feel you were in competition?

Middendorf: I didn’t do that. I looked for what I wanted to do. But I saw a lot of people changing at that time, and I couldn’t believe what money does to people.

Thompson: How do you feel about the market today, and your relationship?

Middendorf: It’s so strange, when you see what the whole art market creates from one day to the other. We had actually a long period for showing die heftige Malerei, and even today there are really a lot of possibilities to do that. But if you see other movements they wanted to create, like neo-geo, it lasted for two seasons and then it was over. And what they do for new American conceptual art—they push it through and then everybody knows it, and what more can they do? The information is so fast now, because there are so many art markets today, and they are very international. On the one hand, that’s fantastic, because you know what happens in Spain, what happens in Italy, what happens everywhere, but on the other hand, Lichtenstein says people look at a painting and they see an amount of money. They don’t see the painting anymore.

Thompson: There have been so many people who have been absolutely ruined by the market. It doesn’t give you a chance to develop.

Middendorf: But we had the time. We were a little bit prepared. It went very fast, but we had worked so long without success before. When we had our own gallery, we didn’t sell anything for three years. That wasn’t important, because we believed in it. But today if you find an artist who has three good paintings, they make a show. Today the artists want to become famous before they paint. It’s because of the big success of these young painters. We have a gallery in Athens; in the last months we have visited lots of young Greek painters, and they all show you some work and say, OK, is it possible to make a big show out of this? But they have just one or two works that really have something of themselves.

Thompson: Are you living still in Berlin?

Middendorf: No, at the moment I work in Berlin and Athens. It’s not so important for me where I work. I work in New York a lot, I worked in Italy over the past year. And I’m sure when you see a catalogue you’re not able to say, OK, this was done here, that was done there. There are some influences in what you paint, in the subject, but not so much in the way you paint it. Because I never cared about light outside; I always paint with electric light.

Thompson: Have you any plans to branch off into other areas, like film?

Middendorf: I did a lot of film in the beginning, and I also taught film at the School of Art in Berlin for three years, until ’82. In the beginning I also did a lot of music. My experience is that you can only do one thing very well. But recently I have worked on big collages, which I’ve never shown. I’ll show them in the next year or so.

Thompson: What materials did you use?

Middendorf: When I paint, I have a lot of papers on the floor with paint on them. One day I started to work with them, because they looked so fascinating. They were like experiments. I have now six or seven big works that really function. The things I show in painting are more like fragments in these collages; I’m sure these collages will influence my painting.

Thompson: What about installations?

Middendorf: Not in terms of putting objects in a room. In ’83, I did a mural in the Kunsthalle Baden-Baden. I painted whole walls, a big environment. It was there for four weeks and then it was overpainted. I did the same thing in an international show in which people were invited to make installations and paintings in the rooms. I did an installation with a big wall painting on one side and flags on the other side. There was an oven in front of the painting, with a pipe, and the whole thing went together and it was fascinating. Maybe I’ll work in the future with this kind of thing, directly on the wall, but I’m not interested in murals. It’s a little bit stupid to always hang paintings so nicely, because you have to find ways to make people really look at painting again. There was a fantastic Penck show in the National Gallery in Berlin last year, and he did a new installation showing paintings. He built walls ten meters high, and on one wall twenty meters long there were fifty paintings. It was like a big collage. That’s one possibility for showing work. Not only the white wall with a painting on it. That’s more a question of presentation.