Guillermo Gomez-Peña & Keith Antar Mason

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS January/February 1993, Vol. 17, issue 1.

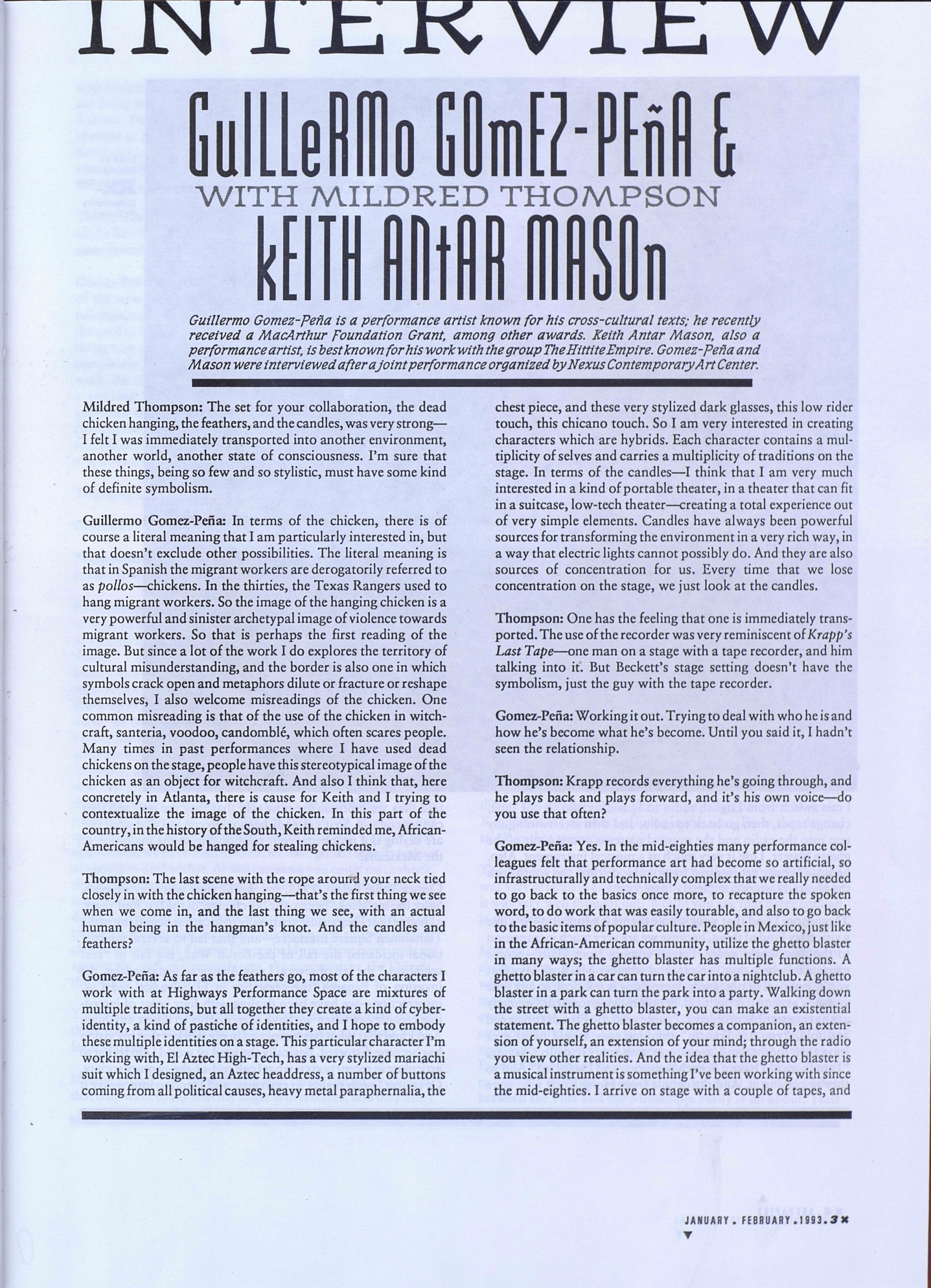

Guillermo Gomez-Peña is a performance artist known for his cross-cultural texts; he recently received a MacArthur Foundation Grant, among other awards. Keith Antar Mason, also a performance artist, is best known for his work with the group The Hittite Empire. Gomez-Peña and Mason were interviewed after a joint performance organized by Nexus Contemporary Art Center.

Mildred Thompson: The set for your collaboration, the dead chicken hanging, the feathers, and the candles, was very strong— I felt I was immediately transported into another environment, another world, another state of consciousness. I’m sure that these things, being so few and so stylistic, must have some kind of definite symbolism.

Guillermo Gomez-Peña: In terms of the chicken, there is of course a literal meaning that I am particularly interested in, but that doesn’t exclude other possibilities. The literal meaning is that in Spanish the migrant workers are derogatorily referred to as pollos—chickens. In the thirties, the Texas Rangers used to hang migrant workers. So the image of the hanging chicken is a very powerful and sinister archetypal image of violence towards migrant workers. So that is perhaps the first reading of the image. But since a lot of the work I do explores the territory of cultural misunderstanding, and the border is also one in which symbols crack open and metaphors dilute or fracture or reshape themselves, I also welcome misreadings of the chicken. One common misreading is that of the use of the chicken in witchcraft, santeria, voodoo, candomblé, which often scares people. Many times in past performances where I have used dead chickens on the stage, people have this stereotypical image of the chicken as an object for witchcraft. And also I think that, here concretely in Atlanta, there is cause for Keith and I trying to contextualize the image of the chicken. In this part of the country, in the history of the South, Keith reminded me, African- Americans would be hanged for stealing chickens.

Thompson: The last scene with the rope around your neck tied closely in with the chicken hanging—that’s the first thing we see when we come in, and the last thing we see, with an actual human being in the hangman’s knot. And the candles and feathers?

Gomez-Peña: As far as the feathers go, most of the characters I work with at Highways Performance Space are mixtures of multiple traditions, but all together they create a kind of cyber- identity, a kind of pastiche of identities, and I hope to embody these multiple identities on a stage. This particular character I’m working with, El Aztec High-Tech, has a very stylized mariachi suit which I designed, an Aztec headdress, a number of buttons coming from all political causes, heavy metal paraphernalia, the chest piece, and these very stylized dark glasses, this low rider touch, this chicano touch. So I am very interested in creating characters which are hybrids. Each character contains a multiplicity of selves and carries a multiplicity of traditions on the stage. In terms of the candles—I think that I am very much interested in a kind of portable theater, in a theater that can fit in a suitcase, low-tech theater—creating a total experience out of very simple elements. Candles have always been powerful sources for transforming the environment in a very rich way, in a way that electric lights cannot possibly do. And they are also sources of concentration for us. Every time that we lose concentration on the stage, we just look at the candles.

Thompson: One has the feeling that one is immediately transported. The use of the recorder was very reminiscent of Krapp’s Last Tape—one man on a stage with a tape recorder, and him talking into it. But Beckett’s stage setting doesn’t have the symbolism, just the guy with the tape recorder.

Gomez-Peña: Working it out. Trying to deal with who he is and how he’s become what he’s become. Until you said it, I hadn’t seen the relationship.

Thompson: Krapp records everything he’s going through, and he plays back and plays forward, and it’s his own voice—do you use that often?

Gomez-Peña: Yes. In the mid-eighties many performance colleagues felt that performance art had become so artificial, so infrastructurally and technically complex that we really needed to go back to the basics once more, to recapture the spoken word, to do work that was easily tourable, and also to go back to the basic items of popular culture. People in Mexico, just like in the African-American community, utilize the ghetto blaster in many ways; the ghetto blaster has multiple functions. A ghetto blaster in a car can turn the car into a nightclub. A ghetto blaster in a park can turn the park into a party. Walking down the street with a ghetto blaster, you can make an existential statement. The ghetto blaster becomes a companion, an extension of yourself, an extension of your mind; through the radio you view other realities. And the idea that the ghetto blaster is a musical instrument is something I’ve been working with since the mid-eighties. I arrive on stage with a couple of tapes, and I can switch from English radio to Spanish radio to one tape, change tapes, then go back to radio, and then intertwining my text into the radio and the musical patterns coming out of the ghetto blaster. I use it very much as a musical instrument. Also, because I really get inspired by popular culture, the youth with the ghetto blasters completely inspires me.

Thompson: I find that your whole theme is prophetic—it’s like a visionary kind of thing, because we are very much in transition to the new world order. People coming from Haiti—people migrate to where they can eat, and whether Mr. Bush says that you’re political or not, every damn thing is political, so any time you seek asylum it is political. People moving towards Germany are having terrible problems. People who the French christened and told, “you are French,” thinking they would never ever leave their motherland, are now getting ready to collect, saying, “I am French! I have a French passport, and I want in!” And so they’re coming in. And the people from Hong Kong who were told they were British are now told that they are not, and they cannot come in. So it’s already begun. Do you feel that what you are saying is a prophecy, your relationship to the migration of the Mexicans?

Gomez-Peña: Before 1988, my world view was very utopian. Since the big smoke began, the big change, of the last four years, a change that I began just artificially to locate as beginning in the Tiananmen Square massacre—and that led to several international incidents, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the fall of “real socialism,” the fall of several Latin American dictatorships, the invasion of Panama, the cease-fire in El Salvador, the L.A. insurrection—we have been dealing with four years of incredible complexity when we have been unable to digest anything. And I find that what has happened in my work is that my vision has become distorted. Basically the kind of world I am trying to articulate in recent texts is what I call end-of-the-century society. Of course I push reality to extremes, and I tend to interweave it with fiction. As I put it in one of the lines of the performance, we are living in a cyberpunk film directed by José Martí and Ted Turner. Yes, I do believe that we are living unprecedented changes at an incredible speed, and we are perplexed by them. Every day I wake up and I turn on the TV, and a major structural change in the world has taken place, and I haven’t even digested the one of the night before.

Thompson: It appears that these are isolated incidents, the fall of the Berlin Wall and so on. Do you feel that it’s really all the same force?

Gomez-Peña: In a sense, I feel that these are really the birth pangs of the new millennium. And especially now—we have been talking about the need to create the epic of the end of the century, the need to find an epic voice to describe this epic drama—we are living now through a series of incredible tragedies. Paraguay is completely flooded, the Iguasu waterfalls just disappeared last week, the city of Guadalajara exploded—several kilometers in a working class neighborhood, and L. A. was on fire. Our continent is going through tremendous pains. And certainly I feel that this is linked with this triple end, the end of the decade and the century and the millennium, and with the beginning of a new society.

Thompson: Do you feel that the new society is already here?

Gomez-Peña: Yes, I do.

Thompson: Keith, I got the impression that your work is all involved with the current political situation.

Keith Mason: No. I cried when I saw that Chinese students and in front of a tank, and heard about them building the Goddess of Democracy, and I said, “My God, America has fooled the world.” I mean, they shouldn’t be building the Goddess of Democracy in China after the Statue of Liberty—that’s a mistake. When the Wall came down in Berlin, I knew for a fact it was going up in South Central—it’s invisible. We have other explosions yet to happen—in Milwaukee, the new Panther Party calling for insurrection in 1995, Jeffrey Dahmer becoming the ultimate vision of what was said back in the ’60s, America eats its young, and black men becoming the victims of cannibalization, fast food on cold weekend nights. Those images haunt me, they live inside me, my work wants to give black men in particular a voice, in all of this, to convey the power of our spirituality, to say we are world healers, and that we have been abandoned, we have been abused, we have gotten over it, and we are going to deal with it. At this moment, you catch me in shock, this is the first time that I have actually created a piece since the insurrection—my colleagues in L.A. don’t know what I’m doing, Guillermo had no idea what it was—I couldn’t get on the phone and talk to him, I couldn’t talk to anyone, this was the first chance to release it. I know I’m probably pushing my friends up against the wall, the empathizers, the progressives, the liberals, the people that I want to be in collective with….

Thompson: But the audience that we had last night, how do you think that they are affected by this, when you say “Fuck you,” for instance?

Mason: I think they immediately shut down and go into denial, that they want to say that my anger is overstated, and they don’t bear the burden of responsibility for my individual pain or the symbolic community that I represent. And I want to hold them responsible. At the same time I know I am not involved in a battle with them; I don’t see them as the adversary, but at the same time I am in a place where I want to express this anger. Because I am in shock right now, and I need time to move from that, to go into grieving, because as a member of Be-Bop, what I am describing—in L.A. we formed an organization weeks ago, months ago to deal with the issues of the black avant-garde, if there is such a thing. We were in crisis prior to April 29; it just escalated with that. So I think my effect on immediate audiences is, people want to shut down, we all want to shut down, we don’t want to talk about it, but we don’t have the opportunity in L.A. to be polite, so everybody is at each other’s throat. We still have questions to ask, we want actions—we wanted Darryl Gates out, that’s the immediate thing that we wanted, but we can’t leave it at that, because there is this whole new society that we are proclaiming is in existence, and we can’t retreat to neo-nationalism, but we do need to take the space and the time to heal ourselves, protect ourselves, and then go on with networking and making other communities vital and important to us—to reach out to those communities and connect with them somehow. So at this moment you catch me saying, “Yeah, I’m in crisis, I’m in shock. I need to tell you why,” and that’s the effect that all this has had on me and my work.

Thompson: Your performance last night for me was really like a continuation of where we left off in the ’60s. In the ’60s, things like this wouldn’t be in the theater, but in someone’s studio, in front of an audience who were on your side. You need to say it on the subway, or you need to stand up in the meat market, or something, and that was why I was asking what you thought the audience response was. Also what you said about denial—there were always more whites than blacks when James Baldwin spoke, and Leonard Bernstein was always accompanying him, et cetera. At Malcolm’s lectures, there were very very few whites, because the message was so strong and nobody wanted to listen to that. Also, the upper-class blacks refused to be seen at Malcolm’s lectures.

Mason: I know that I can perform now in L.A. and I am going to have a Latino audience, an Asian-American audience, as well as a black audience, both intellectuals and what you would call the underclass. Where I am going to do that performance will dictate the demographics. I know that James Baldwin/Malcolm X is part of the dilemma of living in this time, I’m in that dream, stuck in that transition between.

Thompson: The first time I saw Sister Souljah, I thought that she was very articulate and very strong in what she had to say, that it was very well thought out. Would you say that sister Souljah is representative of a new kind of black?

Mason: Definitely. I don’t know where that sense of entitlement comes from, that arrogance—that confidence as well—but when she says “Two wrongs don’t make a right, but it sure makes it feel even,” and brothers on the street today say, “It ain’t even even yet,” then I know that what I am saying is not that extraordinary. People have to wake up to that new voice. That new voice includes a dialogue that isn’t filtered through a Eurocentric point of view; I want to connect with Mexico, I want to connect with the Sudanese and see what the relationship between the Nile and the Mississippi really is all about. Their version of multiculturalism is something entirely different from a Eurocentric definition of multiculturalism here in the States. And when I talk to those members of government who are most excited about my artwork as an African-American, they are totally enthused about supporting my work and hearing our voice and what we have to say—because we don’t want to be beholden to failed integration, that a government wants to token us off, put us in a position and leave us there, stranded and abandoning our true interests. So that’s one part of being an African-American; at the same time, we are blessed by our traditions, and we haven’t forgotten—one of the things I could do during the insurrection was read, and who did I read? The two names you keep coming up with—James Baldwin and Malcolm X—and Dr. Martin Luther King.

Thompson: There are those who say that the problems in the United States are not racial problems, but problems of class. We see things like a man in Hickstown, Pennsylvania, who finished tenth grade but makes fifty thousand dollars a year, has been working at the same job for twenty-three years, has another eight years to pay on his mortgage, but loses his house because he loses his job—this is a white class. Do you think that there will be an insurrection coming from the so-called middle-class whites? Do you think that this would be a point at which these two insurrections could join forces?

Mason: I would hope so. I would hope that then we could put aside our obsession with racism. With that scenario, we’re talking about limited resources. What we found out is that the African-American was supposed to be denied all the resources throughout the history of the United States forever. Now that the resources are really getting smaller, some whites are going to be excluded too, and I hope they wake up and become members of this new, hybrid society that really is not the same, but somehow understands differences and wants to celebrate them and embrace them. That’s what I hope for.

Thompson: In the song “Go Tell It On the Mountain” that goes through all of your performance, the last line says, “Freedom ain’t come, won’t never come.” Is this something that you believe?

Mason: Freedom ain’t never going to come if you’re just walking down the street and waiting for it. Freedom is something that you always have to take. You’re never going to get your freedom, individually, communally, societally if you’re waiting for freedom to actually come knock on your door.

Thompson: How would you incorporate Martin Luther King’s non-violent belief system into your own?

Mason: It was easier for me—but I don’t want to condemn Football. He’s one of the brothers who violently reacted to the injustice, and are now sitting in jail in the Reginald Denney case. The moment I saw that on television I knew they were going to be convicted. But those cops weren’t going to be convicted. So that’s the injustice. But when they took that moment and they defended democracy, they became our liberation fighters. Now I personally have made the decision that I couldn’t do anything like that, but the rage and the violence is in me that strongly I have to use my intellectual abilities to resist, because they were most eloquent in the forms which they chose to express that rage, and the least I can do, is to struggle for them to get their freedom. Now, like Sister Souljah says, two wrongs don’t make a right, but it was beautiful. Here was our warrior culture, that we had nurtured in America, speaking out. It was like a samurai doing his dance before striking him down. Now, I understand the beauty, and I understand the horror, and I’m not going to deny either one of those experiences. And until we get even, justice may have to be won that way for us all, and I’m not going to condemn it. But for me personally, I couldn’t take another human being’s life, I couldn’t be violent with another human being. I want to say I’m filled inside with rage, and the rage says to me, I should create art.

Thompson: I think that my art is very important in any kind of revolution or any kind of anything, but it’s very different when I’m holding a paintbrush and when I’m holding a stick. It may just take too long for you to understand what I’m trying to portray for you in a pictorial way, and that’s why I would rather have a pipe. Also, when you do the slides, there’s a very beautiful moment when we have a slide of the stars and planets, and you have a line that says something like, “Out of a billion stars, why would I be a Negro on this planet?”

Mason: The line goes, “Billions and billions and billions of stars, and I wind up on earth a fucking nigger!” My spiritual self says, “No, that’s not true, that’s somebody else’s definition of who I am, I’m not that and I have some importance in this universe.” I have come to understand that I am living in the contradiction of somebody else’s vision superimposed on me and what I actually am, and I have to struggle every day to remove that vision, and that’s an ongoing struggle.

Thompson: Are you questioning or are you cursing?

Mason: Both. My work is filled with that. I’m conflicted.

Thompson: Is your overall world view pessimistic?

Mason: I’m very pessimistic. I think that one of the reasons that young black men are dying is because we are all afraid of them. Our history is that we are scary beings just by being born, that we need to be handled and supervised and we need to be looked over, and overlooked in other ways and ignored and made totally invisible. And then we participate in that. I’m very pessimistic. At the same time there’s a contradiction; I don’t believe that black men are an endangered species.

Thompson: I know, but the press keeps telling us that. I don’t know whether there is a plan or a system, but for maybe two weeks in Atlanta the headline was “Black Male Endangered Species,” and “Black Males Have Fewer Jobs Than Black Females,” and you open up the paper and read about a mother saying, “I just don’t know what I’m going to do with bringing up these black boys.” So it’s putting a wedge between the black male and the black female that was never there before at this level. At the same time it’s putting a problem between a mother and her black son, because she doesn’t want to be bothered with him—a four-year-old spells trouble, and we’re told that he’s going to be dead by the time he’s nineteen anyway. With this kind of systematic over-and-over-and-over-again, it can make one think “God, what the hell is wrong with me?” and can also make people think, well, black males aren’t going to make it anyway.

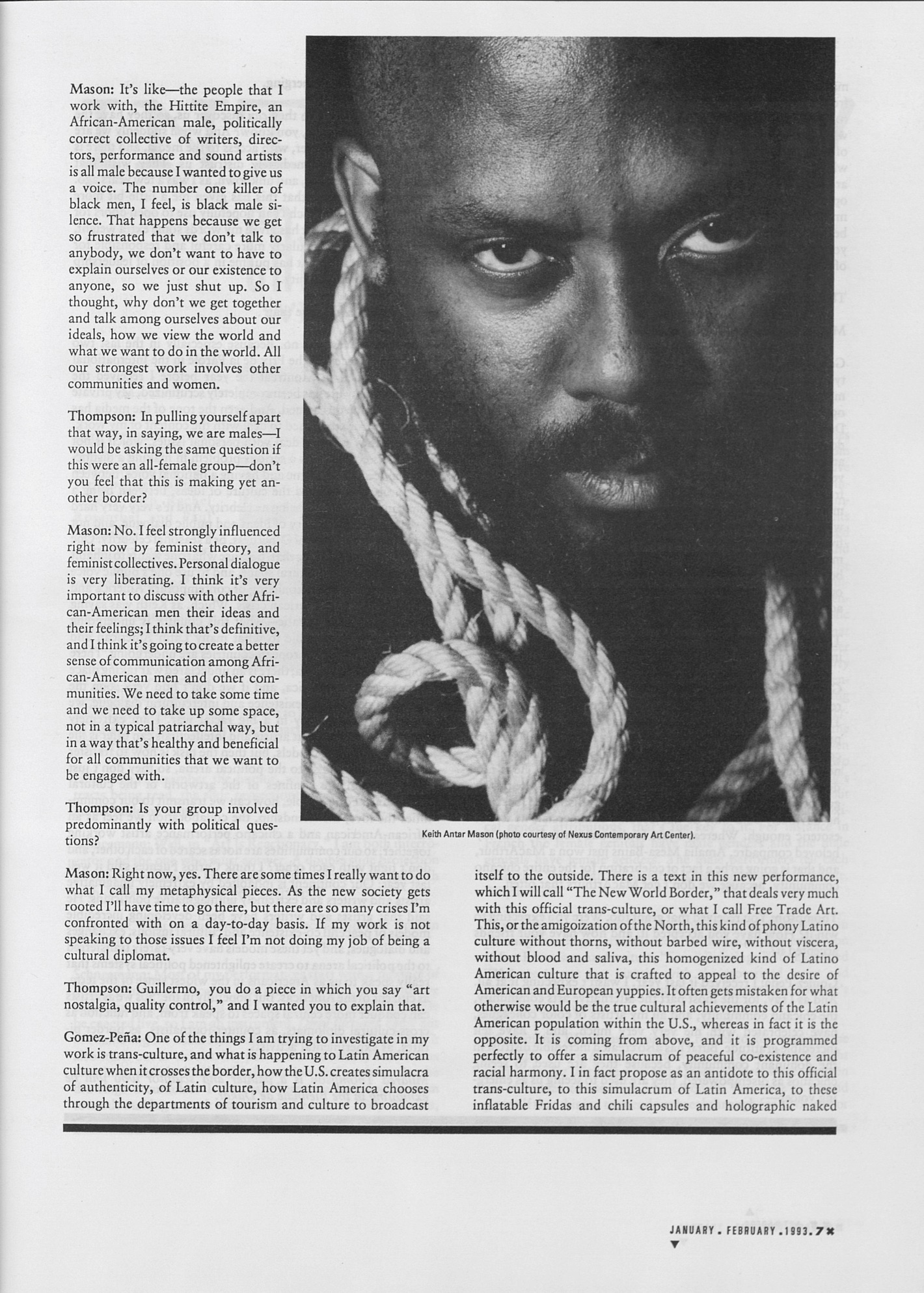

Mason: It’s like—the people that I work with, the Hittite Empire, an African-American male, politically correct collective of writers, directors, performance and sound artists is all male because I wanted to give us a voice. The number one killer of black men, I feet, is black male silence. That happens because we get so frustrated that we don’t talk to anybody, we don’t want to have to explain ourselves or our existence to anyone, so we just shut up. So I thought, why don’t we get together and talk among ourselves about our ideals, how we view the world and what we want to do in the world. All our strongest work involves other communities and women.

Thompson: In pulling yourself apart that way, in saying, we are males—I would be asking the same question if this were an all-female group—don’t you feel that this is making yet another border?

Mason: No. I feel strongly influenced right now by feminist theory, and feminist collectives. Personal dialogue is very liberating. I think it’s very important to discuss with other African-American men their ideas and their feelings; I think that’s definitive, and I think it’s going to create a better sense of communication among African-American men and other communities. We need to take some time and we need to take up some space, not in a typical patriarchal way, but in a way that’s healthy and beneficial for all communities that we want to be engaged with.

Thompson: Is your group involved predominantly with political questions?

Mason: Right now, yes. There are some times I really want to do what I call my metaphysical pieces. As the new society gets rooted I’ll have time to go there, but there are so many crises I’m confronted with on a day-to-day basis. If my work is not speaking to those issues I feel I’m not doing my job of being a cultural diplomat.

Thompson: Guillermo, you do a piece in which you say “art nostalgia, quality control,” and I wanted you to explain that.

Gomez-Peña: One of the things I am trying to investigate in my work is trans-culture, and what is happening to Latin American culture when it crosses the border, how the U.S. creates simulacra of authenticity, of Latin culture, how Latin America chooses through the departments of tourism and culture to broadcast itself to the outside. There is a text in this new performance, which I will call “The New World Border,” that deals very much with this official trans-culture, or what I call Free Trade Art. This, or the amigoization of the North, this kind of phony Latino culture without thorns, without barbed wire, without viscera, without blood and saliva, this homogenized kind of Latino American culture that is crafted to appeal to the desire of American and European yuppies. It often gets mistaken for what otherwise would be the true cultural achievements of the Latin American population within the U.S., whereas in fact it is the opposite. It is coming from above, and it is programmed perfectly to offer a simulacrum of peaceful co-existence and racial harmony. I in fact propose as an antidote to this official trans-culture, to this simulacrum of Latin America, to these inflatable Fridas and chili capsules and holographic naked mariachis that I talk about, I oppose this other culture coming from within, from underneath, this culture coming from a grass-roots level, this culture produced by the various communities who act in friction with everyday reality. There are two sources of identity for us: one imposed by the state, and one coming from within—or multiple identities coming from within, and those are the ones that interest me more; they are much more fluid, open-ended, and they allow for hybrids, for transition, for multiplicity, for duality. For example, there is a difference between the post-earthquake rock-and-roll produced by the youth of Mexico City, which is an attempt to chronicle the pain of the city after the earthquake, this culture of reconstruction.

Thompson: The same sort of thing will happen in Los Angeles…

Mason: It’s happening already in Los Angeles.

Gomez-Peña: —versus the Latino boom created by Broadway tycoons and Hollywood moguls. I think that we often tend to mistake one for the other, but they are very very different. I oppose the Northern model of multiculturalism, which is a Dantean model, the flaneur who descends to the South, who descends to hell, to Latin America, in search of enlightenment, and then comes back to present what he or she has discovered, versus the multiculturalism of the South, which takes power from the state. And although I oppose the Dantean model of multiculturalism, I subscribe totally to the other one, in the same way that I oppose marginality for us who have experienced it for five hundred years—whereas the dominant culture glorifies marginality because it’s an act of privilege for a Western bohemian to be marginal, to live in a bad neighborhood, to hang out with the bad guys, to drink exotic substances, to not have access to the media, to not have a national voice….

Thompson: But they always have their American Express card in their pocket, they don’t leave home without it.

Gomez-Peña: And for us marginality is a five-hundred-year-old reality, and in fact what we want is to speak from the center. That’s why I think that it’s important to not mistake these processes that many people often mistake. In the chicano community, for example, unlike the Anglo-American community, when an artist begins to get some recognition, he is not distrusted. In New York, if an Anglo-American artist begins to get too much recognition, he is immediately distrusted, because he obviously sold out, he has become commercial, he is not esoteric enough. Whereas I just found out yesterday that my beloved compadre, Amalia Mesa-Bains just won a MacArthur, and that is going to be a fact of celebration for the entire chicano community, because we don’t get MacArthurs that often.

Thompson: You received that grant too. Were you expecting to win it? How have you accepted it, and how have your friends accepted it?

Gomez-Peña: I received it last year. I wasn’t expecting it at all. And as I say, for the most part the alternative arts community, the chicano community, and all my artists of color colleagues, have celebrated with me very very much, and I have felt incredible gratitude. But it has also created incredible distrust in the dominant community, because they are used to seeing chicanos as disempowered, they are used to seeing us as emerging voices—

Thompson: Always emerging.

Gomez-Peña: This is so they can discover us, so they have the privilege to discover us, you know? And when suddenly we are speaking from the center, with access to the media, and there is a symmetry, they immediately distrust us. They wish that Guillermo was ill, poor, and unknown, as I was a few years ago. But the good thing is that this has given me a little bit more negotiating power, which I can hopefully use to open doors for other colleagues. And it has given my words some extra weight, and I have to be particularly more careful and responsible for what I say, because that has put me in a position of leadership in the chicano community.

Thompson: Do you like that?

Gomez-Peña: Yes and no. Because especially in the last two years, since I received the Prix de la Parole in the International Theater Festival in Montréal the year before I received the MacArthur, my life has been completely scrutinized. My private life has become threatened. And even the tone of the media has changed. Before they used to deal with the content of my work, and now they want to deal with personal issues, which is not good. This country has a serious problem in making a distinction between having fame and having a national voice, between the culture of hype and the culture of ideas, between being a public intellectual and being a celebrity. And it’s very very hard to remain in the territory of ideas and public dialogue, and not just to become an icon of Otherness, or a seasonal celebrity. One is constantly fighting for that, because what one wants to inhabit is a politicized intercultural space, and to use one’s public voice to participate in the chronicling of contemporary America and the contemporary American crisis. Which, as Keith was saying so eloquently, is dramatic—what this country is undergoing right now is comparable to what many Latin American and African and Eastern European countries are undergoing. There is big trouble in America; there is an undeclared war taking place in the streets of America, and if we don’t find very soon the models of peaceful co-existence and intercultural dialogue, we might end this century in a big racial war. I am extremely worried. I feel that what artists and intellectuals can offer is the creation of utopian models, but then the task is how to transfer these utopian models to the political arena, so they don’t just remain within the confines of the art world or the cultural institutions. For example, how can we transmit to our communities the love, the friendship, the collaboration we feel as an African-American and a chicano performance artist working together, so our communities are not as scared of each other, and don’t fight with each other? I think Carlos Fuentes said it well last year: Our continent is inhabited by extremely imaginative artists and writers and extremely unimaginative politicians. He said that artists and writers have been developing incredible models of peaceful co-existence and cultural fusions, exchanges and dialogues, and yet these models have very rarely transferred to the political arena to create enlightened political systems that really speak to us as Americans in the widest sense of the term, as citizens of the Americas. But hopefully in the ’90s we as artists can conquer more central spaces to speak from, and function as cross-cultural diplomats, as counter-journalists, as border pirates, as experimental activists.