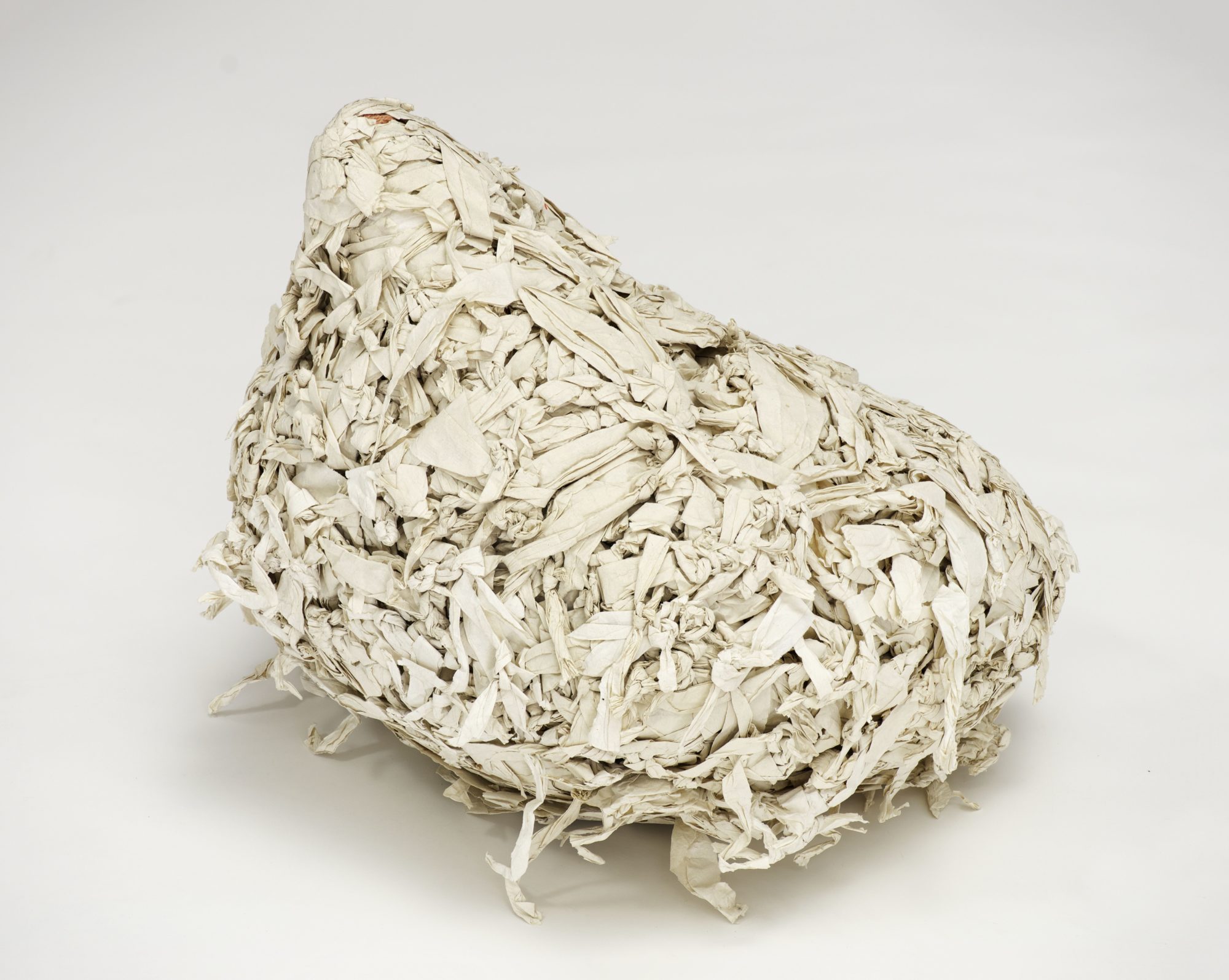

Judith Scott, Untitled, 2003-2004, fiber and found objects, 56 x 28 x 12 inches

[courtesy of The Brooklyn Museum]

Gatecrashing with Katherine Jentleson

Share:

The field of self-taught art has recently evolved from a niche whose leading experts and critics were “no more than a family, both broken and broke, of passionate people with an anarchist [libertaire] inclination”—as stated by pioneering art critic Laurent Danchin (“Art Brut Today,” Raw Vision 82, Summer 2014)—to a globally recognized artistic idiom. With the overwhelming success of James Brett’s touring Museum of Everything, founded in 2009, and its presence at the center of Massimiliano Gioni’s 2013 Venice Biennale, self-taught art—also known as outsider art, art brut, visionary art, outlier art, art singulier, and about half a dozen other labels—has now intimately connected to (some would say “been compromised by”) the institutional networks of the art world at large.

Also in 2013, two major retrospective exhibitions offered a comprehensive overview of what could perhaps paradoxically be described as the emerging canon of self-taught art: the Great and Mighty Things show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Raw Vision exhibition at the Halle Saint-Pierre in Paris. The wave of interest in self-taught artists shows no sign of receding. A Henry Darger show is currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris; and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, has announced an upcoming exhibition on Boundary Markers: Outliers and Mainstream American Art, scheduled for 2017.

Katherine Jentleson’s appointment as the first Merrie and Dan Boone Curator of Folk and Self-Taught Art at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, announced in January 2015, takes place in this context of increased institutional recognition of self-taught art. As the field’s center of gravity shifts toward self-taught artists from the South, the nomination of an up-and-coming curator in this field suggests the pivotal role the High Museum intends to maintain in this evolution. As we seek to understand the present interest, Jentleson’s scholarly work at Duke University has focused mostly on the interwar period, reminding us that the field’s recent success story has an air of déjà vu. Modern art pioneers such as Alfred Barr and Sidney Janis were fervent promoters of self-taught artists—so-called modern primitives—in the 1930s and 1940s; the French self-taught master Henri Rousseau, for instance, features prominently in Barr’s 1936 chart of the development of Cubism and Abstract Art.

One of the reasons for the renewed interest in self-taught art may have to do with the often escapist nature of its perception. A growing number of critics and museumgoers toy with the idea of “forgetting the art world,” to reprise the title of Pamela Lee’s famous essay, perceiving the institution as corrupted by financial speculation and spectacle. Self-taught art is seen as offering a more authentic, “unspoiled” alternative. In his 1968 essay Asphyxiating Culture, Jean Dubuffet, the father of art brut (translated as “outsider art” by Roger Cardinal in 1972), famously compared brut artistic production to desert islands, and institutional cultural production to beach resorts. As Benjamin H.D. Buchloh warned in “The Entropic Encyclopedia” (Artforum, September 2013), his critical review of the 2013 Venice Biennale, the idea of a boundless artistic freedom grounded in the “primeval” purity of the “outsider” artist bears the mark of a mere mythical construct.

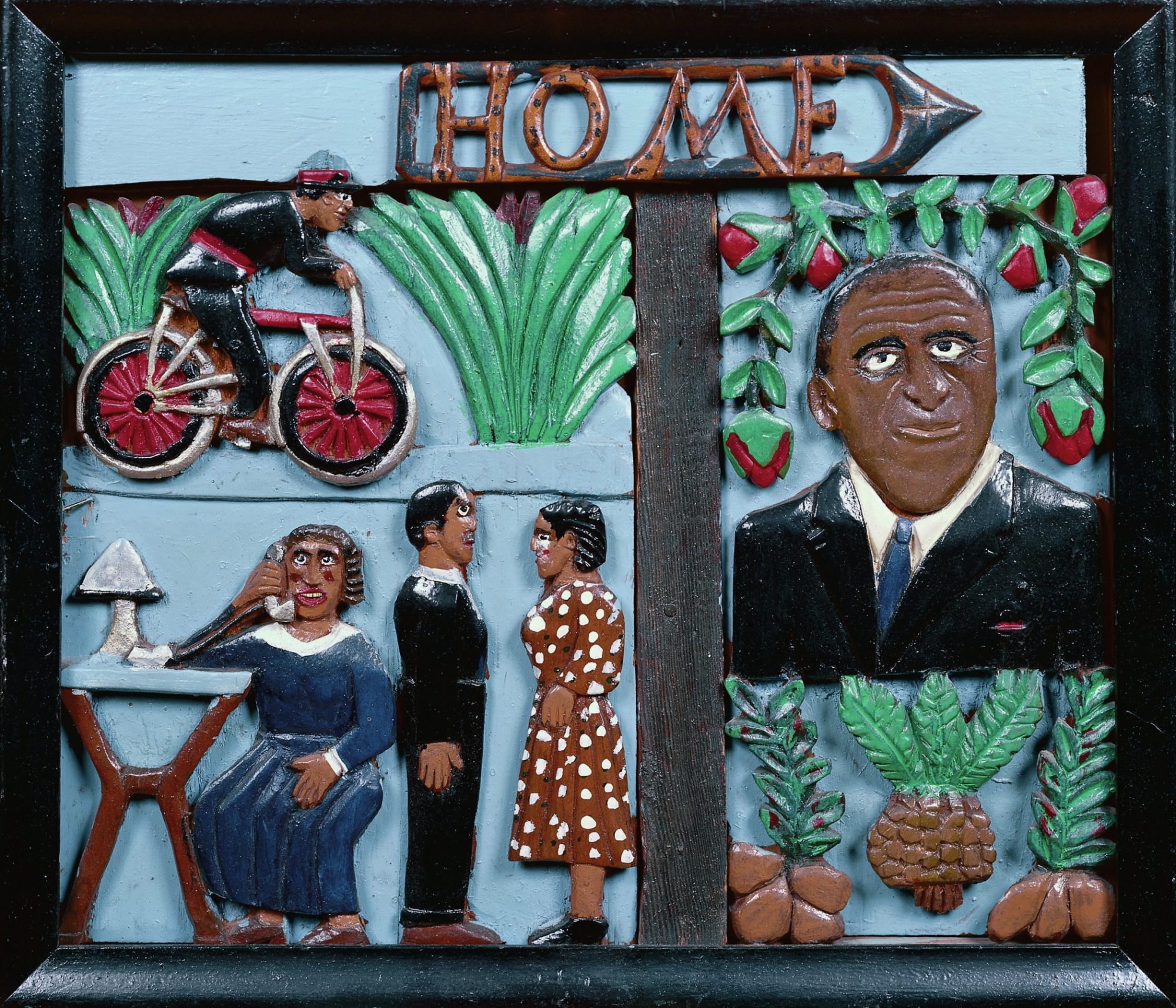

Elijah Pearce, Three Ways to Send a Message: Telephone, Telegram, Tel-e-Woman, 1941, carved wood and paint, 15.5 x 18.5 x 1.5 inches [courtesy of the High Museum, Atlanta]

Yet some of the most exciting exhibitions of self-taught art in recent years have been based on the opposite predicate that “no man is an island.” Groundbreaking shows of work by Ralph Fasanella and Willem van Genk at the American Folk Art Museum in fall 2014 both insisted on the productive interaction between the artist and his context: Fasanella as an indefatigable trade union organizer and community activist, and van Genk as deeply and even obsessively aware of international politics. This emphasis on context changes the perception of these and similar artists, from isolated “freaks” to exemplary voices, often coming from underrepresented or marginalized groups. In that regard, the success of self-taught and outsider art amounts to a real redefinition of the notion of artistic legitimacy, an opening up of the canon that reflects ongoing struggles for social, gender, and racial equality. For instance, the Brooklyn Museum’s Center for Feminist Art’s winter 2014-2015 exhibition Judith Scott: Bound and Unbound demonstrated the richness and complexity of the sculptural accumulations created by a marginalized female artist with Down syndrome.

The latest iteration of the “Southern turn” mentioned above, the overwhelming success of the exhibition When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South at the Studio Museum in Harlem in spring 2014 also participated in this evolution, as it emphasized the relevance and urgency of self-taught and outsider artworks depicting the African American experience in the American South. Katherine Jentleson contributed a major essay, titled “Cracks in the Consensus: Outsider Artists and Art World Ruptures,” to the exhibition’s catalogue. There’s no doubt that in her new position at Atlanta’s High Museum, she will actively contribute to deepening the political relevance and aesthetic resonance of this Southern turn.

Raphael Koenig: What drew you to consider working for the High?

Katherine Jentleson: The High Museum has a long history of collecting and exhibiting folk and self-taught art, which goes back to the 1970s. In 1994 it became the first general museum to have a curator devoted to folk and self-taught art, as opposed to institutions that are entirely devoted to it, such as the American Folk Art Museum in New York, or the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe. The Smithsonian American Art Museum has a fantastic, visionary folk and self-taught art curator, Leslie Umberger, but in the United States, it is still extremely rare for a “general” or encyclopedic art museum to have a department and a position devoted to folk art. That’s really what drew me to this museum: it provides the opportunity to celebrate the legacy of self-taught artists and promote their future from the platform of a more generalized institution that appeals to a very wide audience.

RK: You were hired before completing your PhD in art history at Duke University, which I’m sure will bring some hope to a lot of graduate students out there. How is your current research on folk and self-taught art reflected in your curatorial practice?

KJ: My passion for researching this art began with exhibitions that I saw in New York, roughly between 2007 and 2009, at institutions like the American Folk Art Museum or Galerie St. Etienne. These were really eye-opening experiences: I saw works by artists I had never heard of, like Henry Darger, and historical shows like They Taught Themselves, an important 1942 show of self-taught artists that was restaged at the Galerie St. Etienne in 2009. These were artists who were generally not represented in my art history classes or the American wings of most museums. I just felt this burst of new energy and curiosity to learn more about them, and to try and puzzle out how they fit into the larger story of modernism, contemporary art, and American art. That’s what my research became centered on in graduate school, especially how these artists fit into the larger narratives of American modernism. I now intend to take this passion back out into the exhibition space, to show museumgoers what an important role self-taught artists play in both historic and contemporary conceptions of American and even world art.

Judith Scott, Untitled, 1994, fiber and found objects, 27 x 23 x 17 inches [courtesy of The Brooklyn Museum]

“…it is crucial to think about self-taught art as a field in the way you think of American art as a field, or modern art as a field.”

-Katherine Jentleson

RK: Self-taught and “outsider” art have received a lot of attention since the 2013 Venice Biennale; recently the National Gallery of Art announced it would hold a major exhibition called Boundary Markers: Outliers and Mainstream American Art in 2017. As a young scholar and curator, how do you see this evolution?

KJ: It is such a deeply exciting moment for the recognition of self-taught artists! There is, as you point out, a real surge of interest in how they can add to or change our most fundamental conceptions of art and the artist. I know the NGA exhibition is going to take an expansive historical view of how the art world has interacted with its so-called outsiders, and that is going to open a lot of peoples’ eyes to the fact that before there was the brilliant Massimiliano Gioni, making the self-taught Italian American artist Marino Auriti the centerpiece of his Arsenale exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 2013, Alfred Barr Jr. was grappling with how self-taught artists fit into the [Museum of Modern Art’s] foundational modernist canon with exhibitions like 1938’s Masters of Popular Painting. My dissertation is about that era—the interwar period—and how it really foregrounded the recent renaissance of institutional interest in self-taught artists that we live in today.

RK: In your article “Cracks in the Consensus: Outsider Artists and Art World Ruptures,” you insist on the significance of William Arnett’s 1996 exhibition, Souls Grown Deep. Could you say a few words about the history of Southern self-taught art? What is your understanding of the role of the High Museum within its regional context?

KJ: The mid-1990s moment was crucial for the recognition of self-taught artists. When the Olympics were held in Atlanta in 1996, Arnett organized Souls Grown Deep, perhaps the biggest-ever exhibition of American self-taught artists, with a specific focus on African American Southern “vernacular” artists. This exhibition got a lot of attention, especially from art critics, and has had an important legacy. For one thing, it furthered awareness of the amazing work of Southern African American artists, which had really come to the fore after Jane Livingston’s and John Beardsley’s 1982 Black Folk Art in America show at the Corcoran. That show importantly shifted a lot of attention to the South as being a region that has a huge, amazing legacy of brilliant self-taught artists—something the High was also aware of, and actively promoting. The same year as the Corcoran show, for instance, the High was making a major acquisition of drawings by the Montgomery, AL, artist Bill Traylor, who is now widely represented in international museum collections. And at the time of the Olympics and Souls Grown Deep, the High announced the acquisition of a huge amount of self-taught art from the collection of T. Marshall Hahn, an important supporter of the museum in the 1980s and 1990s. Many of the masterpieces of self-taught art in the High’s collections—works by artists [including] Thornton Dial Sr. and Elijah Pierce—come directly from the Hahn collection.

Howard Finster, The Angel of the Waters #1302, 1979, enamel paint on glass, 18 x 32 inches [courtesy of the High Museum, Atlanta]

RK: Your job title, “curator of folk and self-taught art,” conspicuously avoids the term outsider. What do you think is at stake in this description? What is your own position on so-called term warfare?

KJ: Given the convergence of the output of self-taught and classically trained contemporary artists, and our present sensitivity to the ideological baggage that art labels carry, there is increasingly a call to get rid of all of these terms—outsider, folk, visionary, what have you—altogether. I admire the democratic spirit of this argument, but I also think it is crucial to think about self-taught art as a field in the way you think of American art as a field, or modern art as a field. Self-taught art intersects with those fields, but part of giving it the respect and credence it deserves also means recognizing its uniqueness and historical trajectory. The art world has been debating the labels that best describe these artists since the 1930s, so in my historical work I try to use the terms of the period, which include modern primitive and popular painter. As to how we move forward, even though an artist [such as] Thornton Dial Sr. is increasingly recognized as a great American or contemporary artist, I don’t think that means he should never be shown in the context of folk or self-taught art. Why can’t he be all of the above? Treating the mainstream like it is the high altar to which all artists must aspire just further privileges normative categories.

RK: What about outsider, specifically?

KJ: Outsider art was not meant to refer to American self-taught artists in the first place. It came into circulation as an Anglophone translation of Jean Dubuffet’s art brut when Roger Cardinal published his book on that subject in 1972. Since then, the term really caught on here to describe artists who Dubuffet probably never would have considered to be part of art brut, and its American usage has definite problems. For one thing, it gained popularity in the last quarter of the 20th century, which was also the time that self-taught African American artists from the South started getting major recognition from American museums, and referring to these individuals as “outsiders” has obvious social and political implications. Because the demographics that many self-taught artists represent—whether you are talking in terms of race, ethnicity, geography, religion, gender, or socioeconomic status—are typically underrepresented in the American art canon, they add so much diversity to our conception of who can be considered an artist in America. Terms like outsider further marginalize people who have already been discriminated against in so many ways in their lifetimes. That said, I am fascinated by how it also resonates with a national mythology of difference and exceptionalism that has been building since the moment that the Pilgrims arrived on the Mayflower (or at least since depictions of Native Americans starting circulating in Europe in the late [15th] century). So while I use the term self-taught in most contexts, the term outsider appears in my dissertation title and other publications, because I think there is value in understanding the ways outsider has been used—in reference to self-taught artists, in terms of defining American culture as distinct from its European origins, and especially in terms of how the two are related.

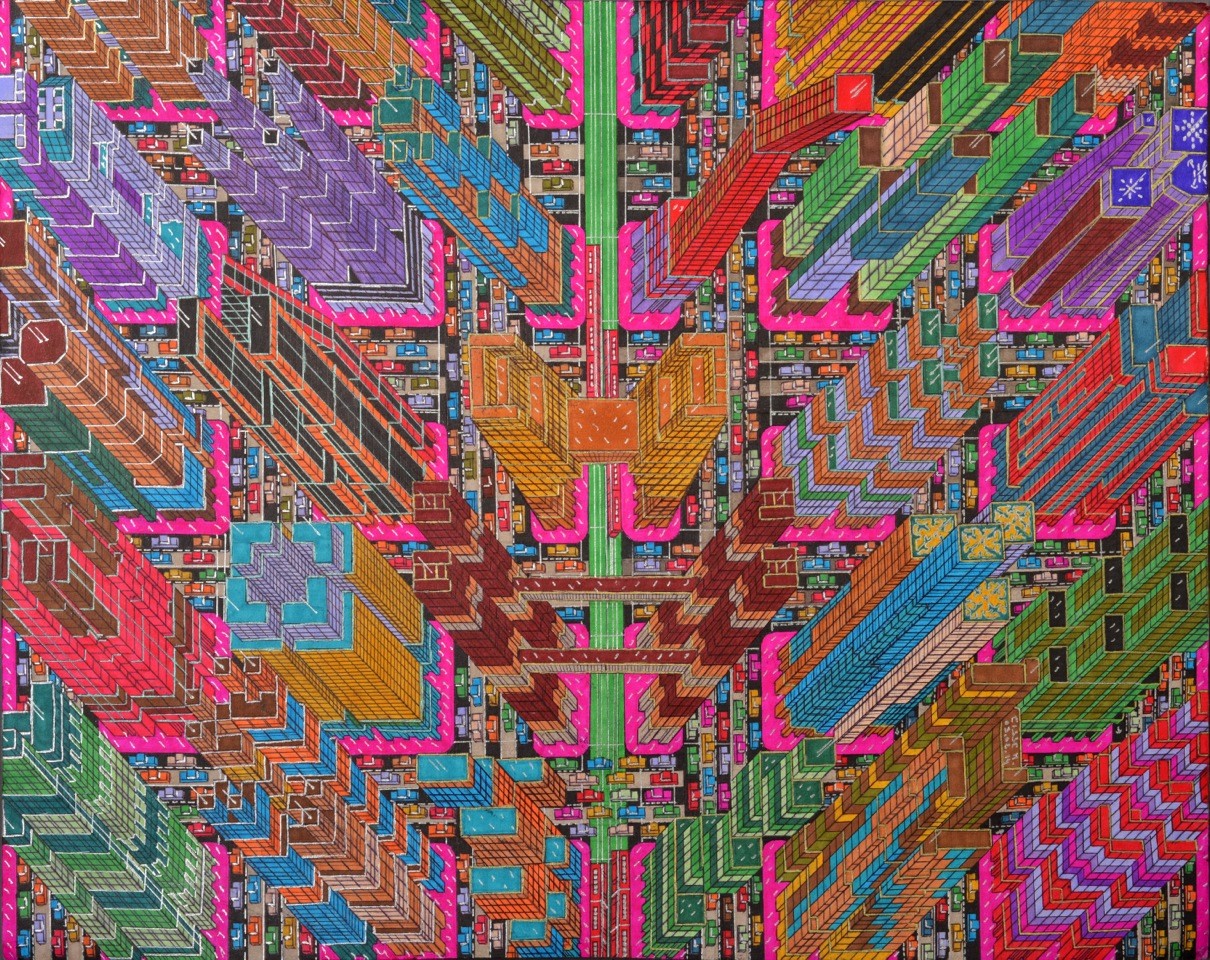

Mamadou Cissé, Untitled, 2014, markers on paper, 40 x 50 centimeters [courtesy of Galerie Degbomey, Fleurance]

RK: How does this relate to your notion of “gatecrashers”?

KJ: In the period that I am writing about in my dissertation, the press frequently invoked the trope of “gatecrashing” to describe the appearance of self-taught artists in mainstream art museums and galleries. There were many self-taught artists who got that kind of recognition between the wars, but I focus on John Kane, Horace Pippin, and Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses because they were by far the most celebrated. John Kane, for instance, “crashed” the Carnegie International, the biggest exhibition of contemporary art in pre-MoMA America, in 1927. He was a housepainter from Pittsburgh, and the press had a field day with the story of how this Scottish immigrant who had lost one of his legs in a railroad accident broke through into the elite art world. The narrative of gatecrashing is repeated for every one of these artists throughout that period. I like it because it’s dramatic, and a big part of appreciating these artists is appreciating how they offered something that was dramatically different for audiences in the period in which they were celebrated, and how their personal stories added a kind of “against all odds” tenor that resonated deeply with Americans. Another important point is that the “gatecrashers” comparison wasn’t coined by art critics so much as newspaper writers, showing a certain conception of the art world as a fortress that is impossible to get into, which I think is interesting as an implicit criticism. Again a key to studying these artists is figuring out not just how they fit into the mainstream, but also how they challenge it.

RK: Do you already have specific projects for the High Museum’s collections, in terms of acquisitions, exhibitions, etc.? Do you intend to foster ties with local folk and self-taught artists?

KJ: I want to take the collection in a lot of different directions. The strength of the collection is Southern, so I’ll definitely continue in that vein, but self-taught artists are also a national and international phenomenon. In terms of artists who are overdue for a reappraisal, Howard Finster, a Baptist minister from Georgia, is someone I am excited to work on. There have been some great shows on his work in the past few decades, but in the 30-plus years he was creating art, he completed more than 46,000 works! So there’s still a lot of work to do on him, and that’s something that’s very much on my agenda, especially since the High has a great collection of his work, and the centenary of his birth will be in 2016. Grandma Moses is another big figure who I think could use more attention. My chapter about her focuses on how her work was promoted in the context of the cultural policies of the Cold War period. Even though people usually associate this period with the promotion of abstract expressionism, there were shows of Grandma Moses’ work abroad in the 1950s and 1960s, supported by the US government. I have a number of other passion projects: I am a nerdy researcher at heart, and I have whole files of names of people I have come across, of whom I thought: “If I could only find a work by this person!” One of them is John T. Hailstalk, an African American elevator operator who lived in New York in the late 1920s and early 1930s and had some shows around that time, but is now utterly unknown. If it’s possible, it would be really exciting to consider self-taught artists, like Hailstalk, whose legacies haven’t stood the test of time against those that have as another way of getting at how quality is judged in this realm of nonacademic art. I’ll be starting work in my new position in September [2015], and I am very excited to begin planning around some of these ideas then.

Raphael Koenig is a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Harvard University, where his work addresses the reception of self-taught art by the French and German avant-gardes. He is also a curatorial intern at the Busch-Reisinger Museum (Harvard Art Museums), and a translator, currently completing the first French translation of Paul Scheerbart’s “asteroid novel,” Lesabéndio (2016).