Angela Ziqi Zhang and Maggie Crowley: Flash, Bang, Fizz

Maggie Crowley, Plaid Work Coat, 2020, gouache on silk, 42 x 42 inches, [photo: courtesy of the artist and Useful Art Services]

Share:

In the summer of 2021, two solo exhibitions in Chicago, one by Maggie Crowley and another by Angela Ziqi Zhang, echoed one another in many ways: connected by the dotted lines of the artists’ friendship and shared history, the presentations revealed common concerns—around value and experience, affect and attention—that play out in both of their practices through distinct visual and material registers.

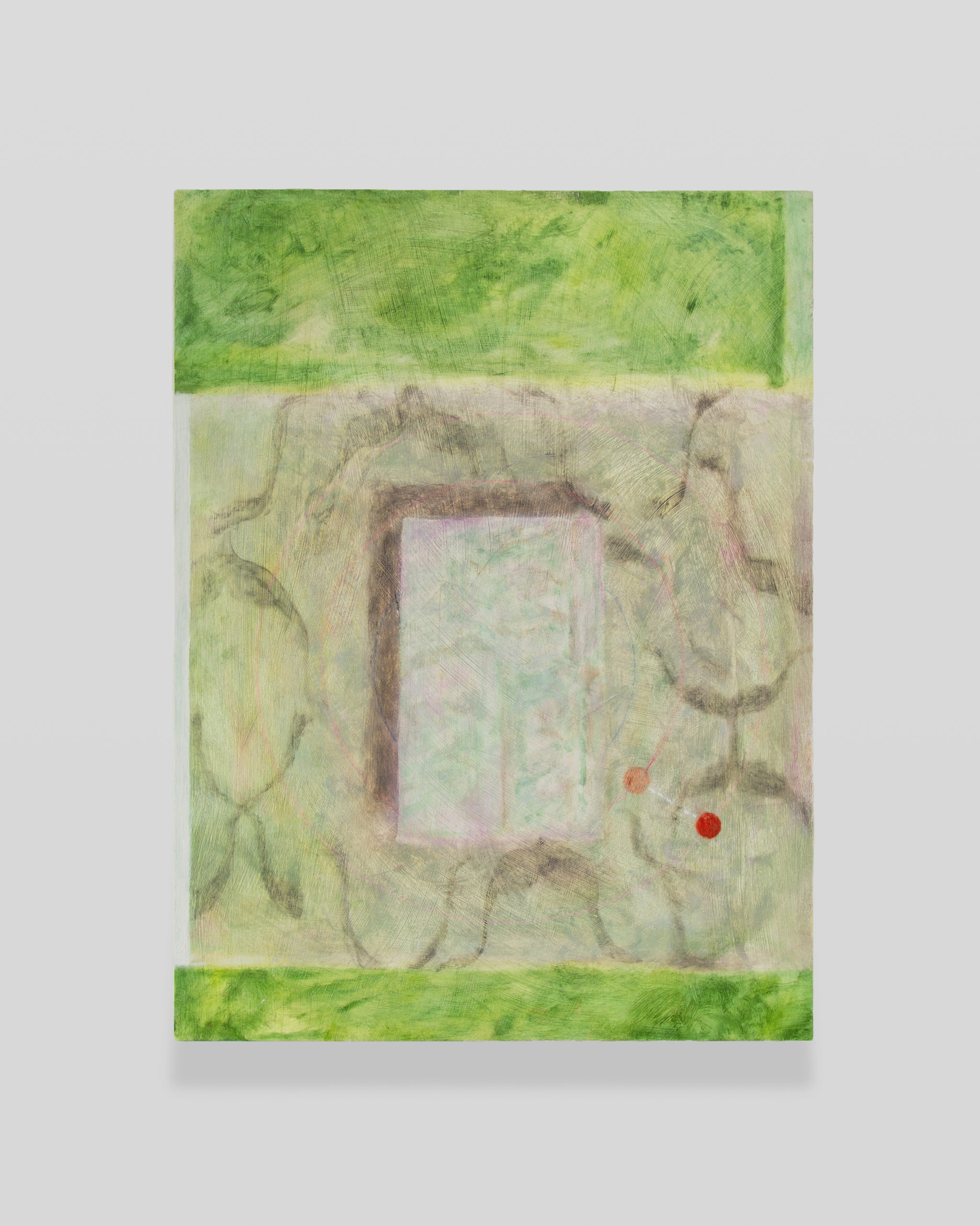

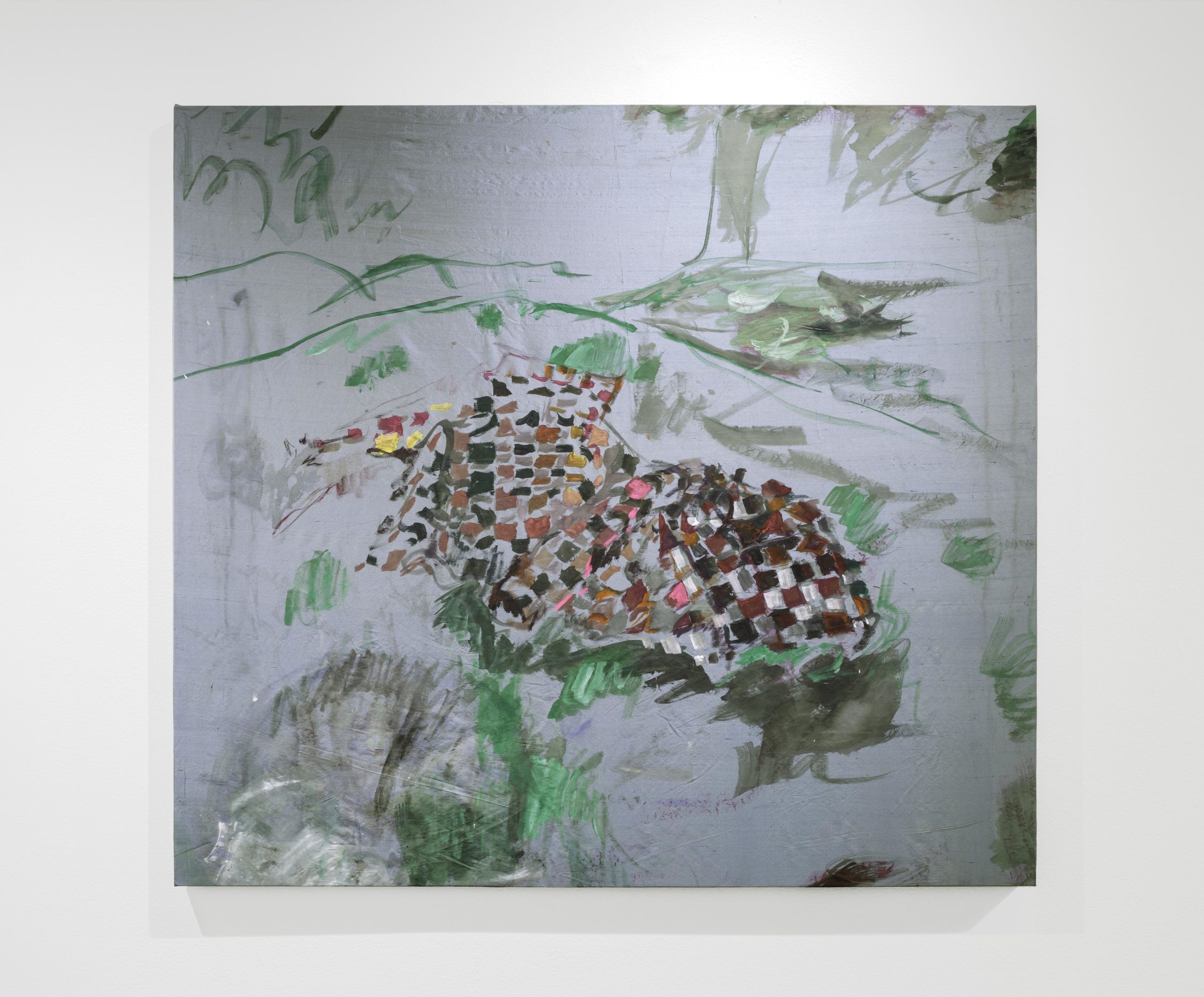

In Playmate at the Hyde Park Art Center (April 12–July 10, 2021), Crowley’s paintings on stretched and unstretched silk hung luminous and fizzing with loose, bright brushstrokes. These were displayed alongside several sewn and cast sculptural objects, safety apparel rendered as ghostly facsimiles. At Produce Model Gallery, Zhang’s Fleece Engine (April 24–June 12, 2021) featured a group of paintings on panel whose hazy and densely layered images are disorienting and inviting. The artists’ work shares a sense of unfixedness, leaning intently into slippery subjects and grappling with the fleetingness of perception.

Zhang’s exhibition was curated by Crowley, who is a co-founder of Produce Model Gallery, and in fact Crowley was Zhang’s first art teacher. Here they reflect together on their influences, their processes, and what they’ve learned from each other.

Angela Ziqi Zhang, Fleece Engine, installation view, 2021 [photo: Maggie Crowley; courtesy of the artist]

Anna Searle Jones: I wanted to start by asking each of you to talk about how you found your way to painting.

Maggie Crowley: I feel like I’m still finding my way to painting. But I started painting as a little girl. I remember making a drawn and painted mark before I remember talking. My mom is a painter and painted in her free time, and it was kind of how I learned about literacy. I’m from a small town, and I went to a rural grade school and a rural high school, and we didn’t have a robust art program, so I took lessons from a woman in my neighborhood. And that’s how I learned about oil paint and watercolor and acrylic and the different media.

Angela Ziqi Zhang: I have a really different intro to painting. I didn’t really make any work until I was in college. And I was planning to be an economics and art history double major. As part of the art history program at University of Chicago, though, you could take some extradepartmental elective courses, and so I thought I should learn more about the making process by taking Visual Arts 101, “On Images,” and Maggie was my teacher [laughing]. It was a 2-D class, but I was making a lot of 3-D work, which is funny because I didn’t instinctively move toward painting. It wasn’t until I took [an oil painting course] that I knew anything about stretching canvas or what oil paint was [laughing]. It was funny because—it sounds corny—I remember I was saying to Maggie after a class, “Jeez, I like making work, I wish I could, like, be an artist.” And she was like, “You should do it.” And that was that. I didn’t really make paintings, though, until after I graduated. And I just came naturally back to still life after not making work for half a year and being an investment banker. And from there I just kept painting.

ASJ: Maggie, I’m curious to hear, apart from your mom’s painting or your neighbor’s painting, were you looking much at other painters? Were you coming into Chicago and going to the Art Institute? And then, on the flip side, Angela, you were an art history major, so you were looking at work for a long time before you started making it. How do you think that shows up in your work?

MC: I was definitely not looking at very much art, especially painting. I went to the Art Institute as a teenager for the first time, with my siblings and my cousins and my mom…. Just being in a museum was overwhelming. Being in a city was overwhelming. Then I started seriously looking at art in undergrad, but I was also studying education. So that’s a ton of research and a ton of administrative work in the philosophy of education and instruction and pedagogy as it relates to art, but more in a technical sense. That was when I knew I wanted to pursue painting more than anything else. [It wasn’t until] I was getting my MA at Eastern Illinois University [that I started] to immerse myself in contemporary and historical art, and then of course [that education continued] when I went on to University of Chicago.

MC: When I graduated I was working a job where I was traveling a lot all over the world and going to the Prado and going to Venice and going to Paris, and seeing Manet in person and seeing Velázquez in person was super life changing. It sounds cheesy, but to see that work in person, after only ever seeing it in a slideshow or a textbook, was super strange.

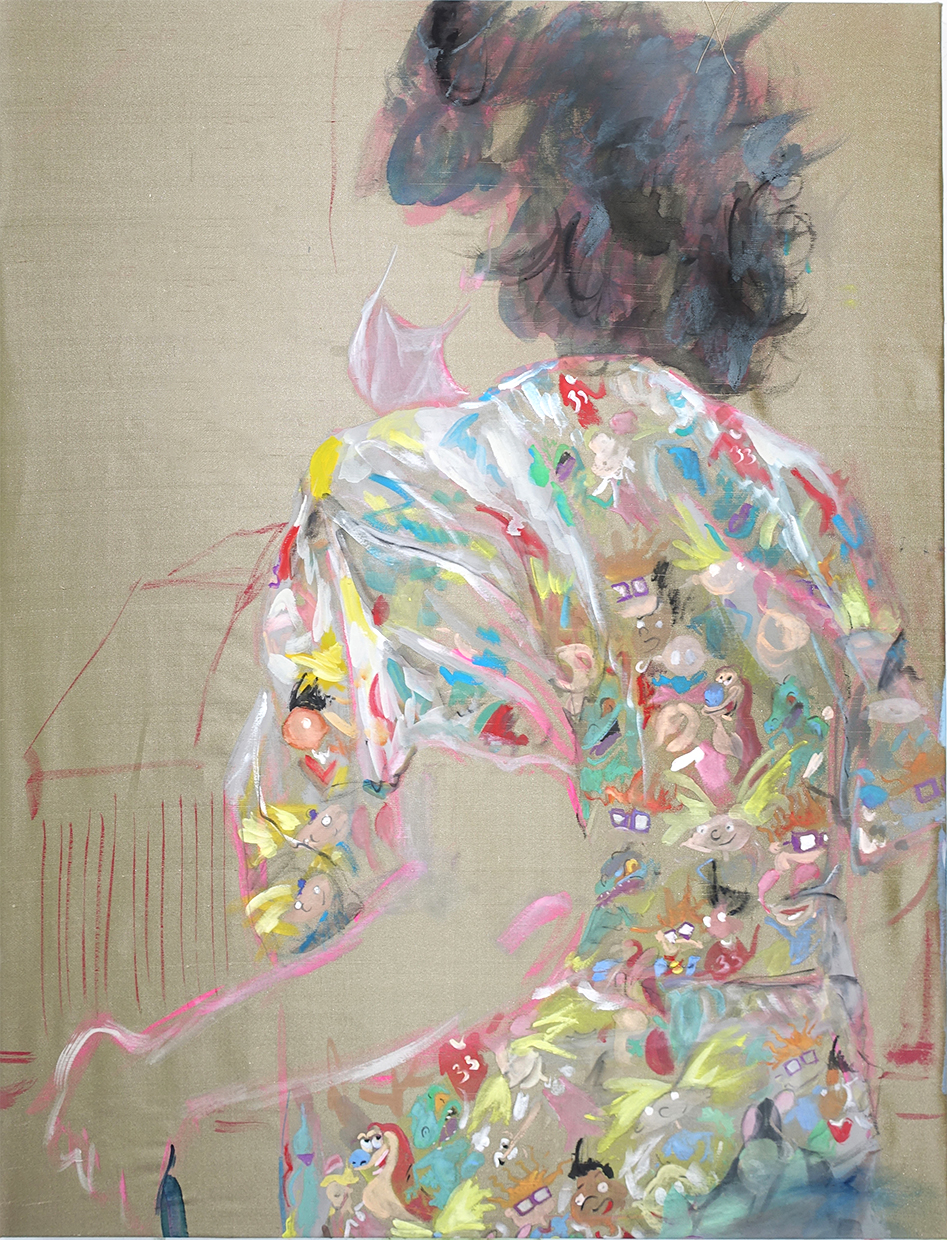

Maggie Crowley, Rugrat Scrubs, installation detail, 2020, gouache on silk, 28 x 20 inches [photo: courtesy of the artist and Useful Art Services]

MC: I feel like I’m still unpacking seeing some of that stuff, even years later. Where you’re at in your life, or what your immediate life experiences are at the time, can temper your entry point to that kind of painting—like Renaissance, really old painting. I feel like I’m still thinking about it pretty much daily.

AZZ: My experience is kind of the same. I’ve never thought about the question of ‘How did I start looking at painting?’ I have an embarrassing answer, which is that I was on the quiz bowl team in high school, and we needed someone to memorize the artists and the famous paintings, and I was like, “That sounds cool. Art seems cool. I’ll do that.” But I didn’t grow up around too much great art in San Diego, so the only art that I got to see in person was in the two museums in downtown La Jolla. I didn’t have access to galleries at all when I was little, and now I [have] so much [access] that I’m lazy to go to museums. But [then it] was like, “Oh if we’re going to a new city, mom and dad, I want to go to the museum so I can see art.”

ASJ: That segues nicely into my next question, which is about visibility. There’s a sense in your work that you take seriously the responsibility and power that comes with making things visible through the act of painting. And I do mean things: Maggie, even in your more figurative works, the human body itself is barely suggested. You see the nurse’s clothing or the high-vis jackets that a number of your subjects wear, but the form of the body isn’t articulated, highlighting instead what you’ve previously called “the textures of a small town.” And Angela, objects are maybe more abstract or anonymous in your paintings, but recognizable shapes of chairs and rings and shoes do emerge. For both of you, the deep personal connection to what you are painting is so evident in the choices you make about how to represent them. I wonder if you can talk about what it means for you for something to be visible, or for you to make something visible.

AZZ: It’s a constant tension for me to try to place to what degree privacy matters to me. But I think over the past two years, the question shifted more from privacy and the personal toward this maybe more philosophical question of what it means to take on the burden of representing at all. I think the objects have naturally become shrouded, or not, in these individual works because I’m thinking of them as symbols more than the actual thing. Or I’m trying to mine the symbol out of the thing. As a result, I think, there is this collapse between object and space that I’m drawn to trying to balance out. At the same time, it becomes this flattening of symbol in plane, and then object in ground. That’s the tension that I’m most interested in. As a result, there is this collapsing of space on itself.

Angela Ziqi Zhang, Fleece Engine, installation view, 2021 [photo: courtesy of the artist]

MC: I think visibility is very political, and when you think of the truth in painting, from every artist’s personal experience, representation becomes a muddy concept. I think of representation—and responsibility and specificity—a lot, in abstract ways. I’m interested in the very subtle tension between abstraction and representation. And what is revealed and what is hidden through painting. That’s also what attracted me to Angela’s work: there are symbols that we recognize, but they are pulled out of their context, so they kind of become something else. That’s the motor of my work. It sort of began with the language of high visibility. There is a lot of blindness toward safety vests and how we interact with them day to day. If you’re not thinking about them, they become something that we almost don’t notice. The iteration of it—to paint the formal lines and structures of a safety vest—in some ways subverts it. When I think of visibility, I also think of iteration a lot. What is a stain versus a mark? What is a dream versus a memory? And understanding that everything always has an origin. There is always the original image, or the original thing, or the original sign, that I’m interested in abstracting, but not through total abstraction, if that makes sense.

I came to focus on labor from sitting in my mom’s hair salon for a month. I considered it a looking residency: just observing her, her clients, and how she worked.

MC: Then I went to my studio and was painting her cutting people’s hair, super zoomed in. I was painting her customers and the way her hand looks when it’s trimming someone’s bangs and how her body is hunched to do that. But none of that conveyed what I was really interested in capturing, which I think is a much more abstract, ontological idea. It was kind of a failed experience. If I had to make a painting or a series of works about [my mom’s hair salon], it would be something to do with the [anti-]fatigue mat that she stands on, and putting that up on the wall or changing the way it exists in the world. But the literal one-to-one interpretation is never successful for trying to capture the essence of something—for me, anyway.

ASJ: Angela, your works in Fleece Engine are almost all oil on panel, with some acrylic and colored pencil. And Maggie, your paintings in Playmate are gouache on silk—some are stretched and others hang like banners, either on the wall or suspended from rods. Both bodies of work are undeniably grounded in painting as a tradition, but they also nod to the sculptural, and—for Maggie—I think also textile arts. Can you talk about these formal decisions that you make and how they play with, or maybe even against, some of your conceptual concerns?

Maggie Crowley, Plaid Work Coat, 2020, gouache on silk, 42 x 42 inches, [photo: courtesy of the artist and Useful Art Services]

MC: I love this question because I love form. It’s super important to my practice, and I also love the formal qualities of Angela’s work. When I’m painting, if I’m using oil or gouache or acrylic paint, washes are super important to me. When I use gouache I use a ton of water, so much that it’s almost uncontrollable. I compare it to the ontological experience of dreaming or remembering because I think those specific mindsets are fuzzy. That fuzziness has holes, and it has entry points. You can fill them in with your own interpretation. For the last ten years, I’ve kept a pretty serious dream journal, and it’s not for the sake of interpretation or finding meaning. I’m interested in the labor of the first thing you do when you wake up, and in how you organize and collect subconscious thoughts. It’s the same headspace [I’m in] when I’m painting. I think the fuzziness sometimes comes across in my work. Angela, we’ve talked about the fuzz, the fleece, that texture in your work that I think is super effective. I also think fuzziness can be slippery. There is fuzziness in dreaming and remembering, but there is also fuzziness in lying, and in theft. I’m interested in how those things can coexist. I think, materially, the silk is hard to pin down, it’s hard to work with. It’s not a fine art material. It’s really expensive. It’s born from the labor of an insect. It’s a resource in the marketplace of the world. It also interacts with light, formally, in a way that I’m interested in.

AZZ: That decision of painting on silk is so interesting because from the side, or when the light hits it a specific way, you can’t see anything. You can’t make out what’s there. It’s just sort of like a glow. You have to approach this thing. It’s almost like a temperamental object.

ASJ: It’s also luxurious, which contrasts with the wool coat that’s just left on the ground [Plaid Work Coat (2020)], or the scrubs [Rugrats Scrubs (2020)]. It gives them a certain dignity.

ASJ: Angela, you mentioned to me that these works were created on pre-cut panels that you were able to obtain during the coronavirus restrictions. [Zhang had previously been cutting her own panels into various irregular forms.] Some of them are circular, and you’ve got a couple of works on conjoined panels. Can you talk about the restrictions and opportunities that working this way presented?

Angela Ziqi Zhang, 2021 [photo: courtesy of the artist]

AZZ: Yeah, I started mostly working on panels consistently when I did my first residency at Vermont Studio Center, early in 2019. I had access to a full woodshop, and I was curious about creating shaped panels, where there was a degree of control over the image as well as the object itself. I always feel like I need to set some kind of parameter, and then the objects and images sort of crawl out, on their own. I have a difficult time visualizing a work at the beginning. I basically never have a plan for it. With these panels that I bought during Covid, it was a shift, because there was not really a parameter anymore, and returning to that blank, rectangular aspect was daunting, because my mind didn’t have any little nook or crevice to start from. I’ve been thinking a lot about the frame lately, and how that serves as another layer of informing how we are meant to view something. I’m interested in what happens when all these different levels—the object, the support, the framing, the composition, the meaning of the image—all sort of flatten together into this one thing. But it was exciting to make works on conjoined panels, because I have also been thinking about the inter-relationality of things. I’m reading Architectural Body by [Madeline] Gins and [Shusaku] Arakawa and also Anti-Oedipus by [Gilles] Deleuze and [Félix] Guattari. There are all these sorts of discussions at a very theoretical level of how things run together, or how we interact with things and with spaces.

AZZ: It was exciting to explore how multiple components of a painting, which in their own right are individual objects, can come together to have a dialogue or make some kind of remark on intersubjective life.

ASJ: Speaking of inter-relationality, how did these particular bodies of work in Fleece Engine and Playmate come together, and how do the works operate in relation to one another within each exhibition?

AZZ: A good amount of the work was made before I knew I was having the exhibition. Another chunk of it was actually made after Maggie and I had already planned the exhibition’s opening and set a date. It was eventually pushed back about five months because of Covid. Maggie had already drafted the press release—actually, it was this wonderful gift. The line that was the most directive, or that I felt compelled to keep in mind while working on the latter half of the body of work, was that my work was like driving a car. I’ve just been driving so much because I’ve had my car in Brooklyn, and it’s a whole ordeal to have a car in the city. And I’m thinking a lot about the shapes of how I see things moving by. Intersubjectivity was a big aspect in how I was working thanks to Maggie’s writing. That was a special treat.

MC: When Angela and I first started talking about her show, I was reading [Jean] Baudrillard’s America. There is this sentence right at the beginning, where he writes: “Driving is a spectacular form of amnesia. Everything is to be discovered, everything to be obliterated.” I thought it was so perfect. It’s just a great idea to think about, but also in relation to Angela’s work and my own. I think what he’s talking about with amnesia is like the sister to abstraction. But I also think this book sort of mythologizes North America. In talking about driving, it’s the phenomenological experience of driving [I’m interested in]. I’m also interested in commuting and maintenance….

MC: As a whole, I see Playmate as this collection of objects that talk about sentimentality and peace of mind, and the insidious side of those things too. When you’re thinking of hard work and bootstrapping, there is an archetype for this figure. It’s usually a White, blue-collar male. It’s someone with a hard hat and a hammer. The truth is that women and immigrants make up most of the working class of this country. With Playmate, I’m interested in what comes to mind first when we think about safety apparel and work; then what comes to mind later; then what the actual truth is; and how all those things exist in the room together—they might be in harmony, they also might be at odds.

Maggie Crowley, Class III Safety Garment, installation view, 2020 [photo: courtesy of the artist and Useful Art Services]

Maggie Crowley, equipment of the Earth, 2020, gouache on silk, 92 x 78 inches, [photo: courtesy of the artist and Useful Art Services]

ASJ: I wanted to close by asking each of you to speak to the other’s work and what you’ve learned from each other—what you, as artists, have gained from your relationship.

AZZ: Maggie is a huge figure in my painting career; or, the journey started with Maggie. Which is a lot to put on a person, but when I was first in that class that she taught, I remember looking at her website and being like, ‘This person makes the kind of work I want to make.’ There was this beautiful, sort of lusty or enticing quality to the bright colors, the soft colors, the way they were interacting. Then, the consideration of material. Every part of the support of Maggie’s works is just so thought through. She is constantly mining what painting is and arriving at these very specific materials and these very specific objects to represent.

MC: I think there is a lot of possibility in Angela’s work. Angela curated the playlist we listened to while we were painting the walls and hanging the show. All of these works were talking to and informing each other and singing to the music. That is all Angela. That is all her little moves and her big moves. Hanging Angela’s work and being able to touch it and handle it was so fun and almost erotic. You get super close to it, and there is this universe of colors and layers and washes. It almost feels like it’s reaching back out at you or it’s going to change or something. That energy that is poetic but also serious is my favorite, and it’s why I love the work.

MC: It said a lot that the experience of hanging Angela’s show felt like a party. The whole experience was like friends chipping away at work a little bit, talking and sharing. Everything just seemed so interconnected in a way that people work really hard to try to achieve. Whereas Angela’s practice just exudes that, and it’s very natural.

AZZ: … When I went to see Maggie’s exhibition, I was alone in the Hyde Park Art Center. The process of viewing, for me, was like a chapter book. Each work has so much to parse through, and every painting is different from every angle. Walking down the hallway and back up again, I was thinking of the word flash, like a bang, or an echo, or something. Each one pops and fizzes. But then when you look at it, and look into the objects, they just sort of dissolve and then reappear again. There is a generosity of gesture, a generosity of the hand in the work. And I love it [laughing].

Anna Searle Jones is a writer, editor, and administrator in Chicago.